New Migrations

The depression was a boon to anyone who had inexpensive housing to rent; especially for inexpensive hotels, hard times meant steady and often overflow business. In skid rows, older and more desperate casual workers piled up. Among the many new urban residents were married men from farms and small towns who left their families to look for work in the city and young girls who shared rooms while they worked as secretaries, putting off college or starting a family. While managers of San Francisco's expensive hotels worried about staying in business—occupancy rates at the better hotels often fell below 60 percent—owners of Western Addition rooming houses found that by cutting repairs they could maintain an after-tax income ranging from 8 to 17 percent.[2]

After 1939, employment surges for World War II production overwhelmed every price level of hotel housing in America and led to the all-time peak in hotel residents. At the better hotels, managers gave priority for rooms to foreign diplomats, production contractors, and military officers in special training. Occupancy rates averaged more than 82 percent, higher than the best rates of the 1920s. However, at many good hotels social elegance and lavish meals faded.[3] Elsewhere in the city, landlords—with the blessing of local and federal emergency housing offices—hastily converted buildings into rooming houses or cheap lodgings. In the districts close to San Francisco's downtown, conversions created hundreds of new rooming houses.[4] Rosie the Riveter and her male colleagues found themselves in emergency dormitory and barracks-style housing, often modeled on traditional lodging and rooming houses. In addition, one nondefense worker moved to the cities for every war-related worker; more than half lived in single-person households, and most were under thirty years old. These wartime conditions caused social workers to worry that one-fourth of the young

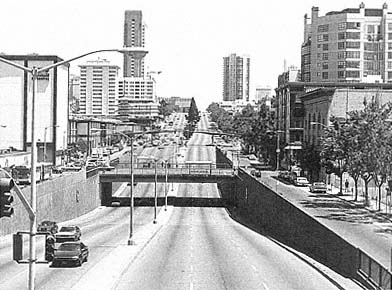

Figure 9.1

Geary Street in the early 1950s, before urban renewal. A commercial

node in a hotel district in the Western Addition, San Francisco.

Figure 9.2

Geary Street at the same location, 1992, after urban renewal. A few older

buildings, middle right , survive, but the new rules of land use, building type,

and transportation have eliminated the former rules of the street.

male migrants were "living in flophouses and cheap hotels in the worst sections of the city." In racial ghettos where restrictive covenants constrained expansion, the influx of new minority war workers often meant severe overcrowding.[5]

Ten years after the wartime boom, residential hotel life was beginning to wane in the older expensive hotels, which were catering more to conventioneers than to smaller numbers of local elites. Rent controls imposed on hotel keepers during the war had also made them wary of permanent residents. At the new palace and midpriced hotels of the 1950s and 1960s, owners looked strictly for transient and convention business. To keep prices down for the new clientele, managers ordered chefs to find additional ways to trim the elegance of their menus and service; culinary talent scattered, and private restaurants took up more of the deluxe dining business.[6] The conversion of most top hotels to strictly tourist business helped to stop a 150-year pattern—the generational shift of elite permanent guests from a fading hostelry to the next largest and more socially prominent hotel. The dwindling population of middle and upper class hotel residents entrenched themselves where they were. The middle-aged and elderly high-income residents tended to collect at fewer and older hotels that maintained more traditional dining service and avoided conventioneers. The new social elites, if they lived downtown at all, usually did so in exclusive apartments perched on top of parking garages. The entrenchment in palace hotels cut into the former glamour of hotel life as the number of glittering and notable permanent guests declined. It also interrupted the process of filtering. Fewer good residential rooms were being vacated; hence, fewer residential rooms filtered to a lower price range.

Even after World War II, the rooming house market flourished as a result of the continuing influx of single and mobile young adults, most without cars. Organizations of boarding homes for women remained active into the mid-1950s. In 1951, the creators of the science fiction film The Day the Earth Stood Still could present rooming house life lived by a single mother. The suburbs held few housing opportunities for these young people; suburban jobs and the new, boxy blocks of inexpensive suburban apartments would not be created in sufficient numbers until about 1960. Meanwhile, in neighborhoods near colleges and technical schools, the boom in enrollments during the 1940s and 1950s kept whole blocks of rooming house establishments busy. Yet

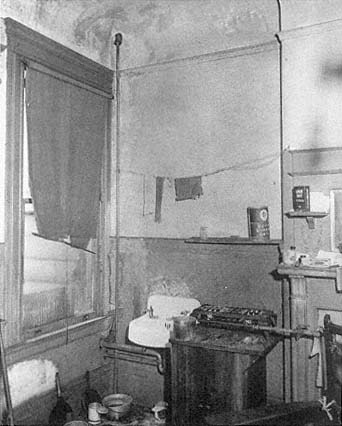

Figure 9.3

Jerry-rigged sink and hot plate, Western Addition, 1949.

Slum conditions in this San Francisco neighborhood's

light house-keeping rooms had been exacerbated

by World War II overcrowding.

some supplies of rooms at this price range were literally losing ground. Middle-income families in houses and apartments less often needed to take in roomers. The roomers still in the market were less likely to be of the same race or ethnicity as the landlady, further discouraging rooming house life. In the better neighborhoods, many owners of small midpriced hotels converted their buildings to apartments by adding kitchens and private baths, often with public assistance. Particularly in tenement districts or racially transitional neighborhoods, overcrowding, poor management, and the accumulation of needed repairs turned hastily converted wartime rooming houses into slum housing (fig. 9.3).[7]