Chapter Nine—

Prohibition versus Pluralism

Residential hotel life came close to being completely eliminated in many American cities between the depression and the 1980s. During those decades, American investors reconfigured the urban economy and the meaning of downtown. By stretching the city in some places, they forced changes in others, simultaneously rearranging the way people used all four ranks of hotels (figs. 9.1, 9.2). These changes did not eliminate the hotel market, as some hoped; however, they altered it substantially and created the base for the SRO crisis.

A central aspect of hotel life after 1930 is that it depended on an aging supply of buildings; virtually no one built a new residential hotel between 1930 and 1980.[1] During those years, changes in residential hotel supply occurred roughly in three phases. From the depression to 1960, most observers saw an oversupply of hotel rooms. From 1960 to 1970, the SRO crisis became apparent, and Americans began to forge new policies concerning hotels. Since 1970, continuing losses and problems have been balanced with increasingly widespread attempts to stabilize existing hotels and to construct new ones. The hard-won continuation of hotel life reveals the importance of minority choices—both public and professional—in making public policy.

Losing Ground:

Changing Contexts, 1930–1970

Although urban renewal alone is often blamed for the SRO crisis, earlier and more diffuse forces also sharply affected the residential hotel market. These included work place shifts caused by the depression, World War II, and office expansion, as well as shifts in highway and parking construction, American traditions of retirement, and the treatment of mental illness.

New Migrations

The depression was a boon to anyone who had inexpensive housing to rent; especially for inexpensive hotels, hard times meant steady and often overflow business. In skid rows, older and more desperate casual workers piled up. Among the many new urban residents were married men from farms and small towns who left their families to look for work in the city and young girls who shared rooms while they worked as secretaries, putting off college or starting a family. While managers of San Francisco's expensive hotels worried about staying in business—occupancy rates at the better hotels often fell below 60 percent—owners of Western Addition rooming houses found that by cutting repairs they could maintain an after-tax income ranging from 8 to 17 percent.[2]

After 1939, employment surges for World War II production overwhelmed every price level of hotel housing in America and led to the all-time peak in hotel residents. At the better hotels, managers gave priority for rooms to foreign diplomats, production contractors, and military officers in special training. Occupancy rates averaged more than 82 percent, higher than the best rates of the 1920s. However, at many good hotels social elegance and lavish meals faded.[3] Elsewhere in the city, landlords—with the blessing of local and federal emergency housing offices—hastily converted buildings into rooming houses or cheap lodgings. In the districts close to San Francisco's downtown, conversions created hundreds of new rooming houses.[4] Rosie the Riveter and her male colleagues found themselves in emergency dormitory and barracks-style housing, often modeled on traditional lodging and rooming houses. In addition, one nondefense worker moved to the cities for every war-related worker; more than half lived in single-person households, and most were under thirty years old. These wartime conditions caused social workers to worry that one-fourth of the young

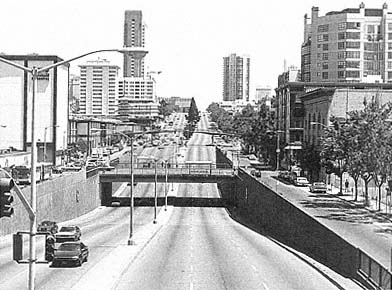

Figure 9.1

Geary Street in the early 1950s, before urban renewal. A commercial

node in a hotel district in the Western Addition, San Francisco.

Figure 9.2

Geary Street at the same location, 1992, after urban renewal. A few older

buildings, middle right , survive, but the new rules of land use, building type,

and transportation have eliminated the former rules of the street.

male migrants were "living in flophouses and cheap hotels in the worst sections of the city." In racial ghettos where restrictive covenants constrained expansion, the influx of new minority war workers often meant severe overcrowding.[5]

Ten years after the wartime boom, residential hotel life was beginning to wane in the older expensive hotels, which were catering more to conventioneers than to smaller numbers of local elites. Rent controls imposed on hotel keepers during the war had also made them wary of permanent residents. At the new palace and midpriced hotels of the 1950s and 1960s, owners looked strictly for transient and convention business. To keep prices down for the new clientele, managers ordered chefs to find additional ways to trim the elegance of their menus and service; culinary talent scattered, and private restaurants took up more of the deluxe dining business.[6] The conversion of most top hotels to strictly tourist business helped to stop a 150-year pattern—the generational shift of elite permanent guests from a fading hostelry to the next largest and more socially prominent hotel. The dwindling population of middle and upper class hotel residents entrenched themselves where they were. The middle-aged and elderly high-income residents tended to collect at fewer and older hotels that maintained more traditional dining service and avoided conventioneers. The new social elites, if they lived downtown at all, usually did so in exclusive apartments perched on top of parking garages. The entrenchment in palace hotels cut into the former glamour of hotel life as the number of glittering and notable permanent guests declined. It also interrupted the process of filtering. Fewer good residential rooms were being vacated; hence, fewer residential rooms filtered to a lower price range.

Even after World War II, the rooming house market flourished as a result of the continuing influx of single and mobile young adults, most without cars. Organizations of boarding homes for women remained active into the mid-1950s. In 1951, the creators of the science fiction film The Day the Earth Stood Still could present rooming house life lived by a single mother. The suburbs held few housing opportunities for these young people; suburban jobs and the new, boxy blocks of inexpensive suburban apartments would not be created in sufficient numbers until about 1960. Meanwhile, in neighborhoods near colleges and technical schools, the boom in enrollments during the 1940s and 1950s kept whole blocks of rooming house establishments busy. Yet

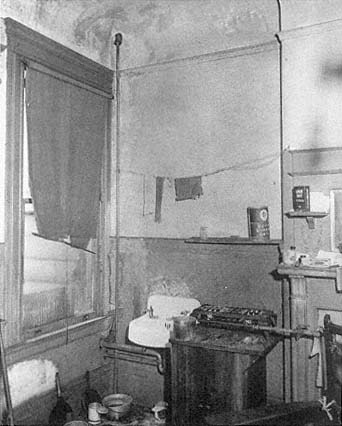

Figure 9.3

Jerry-rigged sink and hot plate, Western Addition, 1949.

Slum conditions in this San Francisco neighborhood's

light house-keeping rooms had been exacerbated

by World War II overcrowding.

some supplies of rooms at this price range were literally losing ground. Middle-income families in houses and apartments less often needed to take in roomers. The roomers still in the market were less likely to be of the same race or ethnicity as the landlady, further discouraging rooming house life. In the better neighborhoods, many owners of small midpriced hotels converted their buildings to apartments by adding kitchens and private baths, often with public assistance. Particularly in tenement districts or racially transitional neighborhoods, overcrowding, poor management, and the accumulation of needed repairs turned hastily converted wartime rooming houses into slum housing (fig. 9.3).[7]

Making Room for Offices and Cars

The most overt pressure on residential hotels came from the expansion of downtown office and retailing districts, which began again in earnest with the urban renewal of the 1960s. The case of San Francisco is typical. A downtown growth coalition of retailers and real estate developers was expanding the

downtown to accommodate the huge increase in office work created by the immense investment wealth of California and the city's expanded role in Pacific Rim trade. In the 1930s, total office space in San Francisco had stayed nearly static. During the 1940s, developers doubled the city's office capacity, often using lofts and temporary space. During the 1950s, owners made the wartime increases permanent, and capacity grew another 30 percent, making San Francisco fourth in the nation in terms of total office space. By the mid-1970s, San Francisco was second only to New York City as a center of international commerce and banking, second only to Boston in its ratio of office space to population. For the millions of square feet of additional office buildings needed, developers began to bid for sites in the South of Market.[8]

Simultaneously, other government policies and private speculative investment patterns also eroded the basis for hotel living. The sheer primacy and publicly secured profits of suburban single-family houses overshadowed most notions of investing in downtown apartments or residential hotels. Continuing policies of redlining meant that lending institutions often refused loans to rooming or lodging house areas. Meanwhile, at least in San Francisco between World War II and 1960, a generation of hotel owners literally died out. Unlike the patterns of the past, the inheritors (who no longer lived in the city but in elite suburbs) sold the hotels their forebears had built. They invested the money in suburban real estate they understood or in other sectors of the economy. Those prosperous optometrists who still lived in San Francisco's Pacific Heights were more likely to band together to build a medical office complex in suburban Dallas than to buy anything in the South of Market.[9]

Transportation investments acted on yet another series of fronts. To connect the new suburban city with the rebuilt downtown, traffic engineers and automobile-owning consumers called for new freeways and plentiful parking. Downtown highway and garage building hit directly at rooming and lodging house areas, beginning as early as the 1930s. California's transportation engineers planted highway approaches and viaduct routes—first for the Bay Bridge and later for freeways—directly through San Francisco's South of Market and the Western Addition, demolishing thousands of hotel rooms.[10]

Although highway construction leveled lower-cost hotel blocks, the automobile was not inherently an enemy for people living in midpriced

and palace hotels, at least not in the short run. If anything, for the middle and upper class, automobiles could be a boon to living downtown. In the early 1920s, a study at a south side lakeshore hotel in Chicago found one-fourth of the permanent residents had cars. Where motels cut into downtown tourist business, hotel managers could cater to additional permanent guests. To compete with motels, hotel owners also obtained garages and prominently advertised their parking. Permanent guests with automobiles enjoyed garage access as well; some small hotels offered backyard or side yard parking (fig. 9.4).[11] Thus the automobile per se did not seriously affect hotel housing choice.

In the long run, however, and for the majority of hotel residents, automobiles and hotel life did not mix. The residents of downtown rooming and lodging house neighborhoods found themselves looking out at freeway ramps or giant ditches built for six lanes of traffic, or contending with traffic noise and exhaust generated by automobiles on new through-roads and one-way pairs of downtown streets. In the areas of former single-family houses that owners had converted to rooming houses by the 1950s, parking became a major issue. Planning authorities wrote that parked cars without proper off-street spaces automatically caused blight. Neighbors harangued rooming house owners to provide off-street parking so their tenants' cars would no longer clog the streets or fill unsightly vacant lots (fig. 9.5).[12]

Other Changes for Hotel Tenants

As suburban employment surged for people with cars, the situation for non–car-owning residents of cheap rooming and lodging houses became grimmer. White-collar work continued to boom downtown, but blue-collar work did not. As part of the shift of use from streetcar and railroad to automobile and truck, workshop employers and shipping firms moved to outlying highway locations. San Francisco's port lost cargo traffic to more modern ports; buildings in San Francisco's South of Market became underused. Elsewhere in the downtown, employers were eliminating jobs through mechanization. Supervisors called for steadier family-tied workers instead of politically volatile, floating groups hired for short periods. Adoption of shorter workdays meant that more employees had time for commuting to more distant homes. These factors drastically changed the needs for downtown housing and the social roles of workers' districts. Younger laborers and family men did not pass through the skid

Figure 9.4

Small residential hotel with automobile

parking in the back. The Hotel Eddy,

with about 16 units, was a concrete

frame structure built in the early 1920s

in San Francisco's Western Addition. The

two carports at the back sheltered 10 cars.

Figure 9.5

Informal parking lot adjoining a rooming house in Omaha, Nebraska, 1938.

row as often as they had in the 1940s. Older, hard-to-employ men and the home guard were no longer a substrata but a primary proportion of the population (fig. 9.6). By 1960, welfare departments were referring more unemployed downtown people—especially the elderly—to hotels for temporary housing that tended to become permanent. As Joan Shapiro has written, this was often the beginning of an unplanned and unwilling interdependence between social services and hotel owners.[13] In 1961, officials from Minneapolis, Kansas City, and Norfolk seemed confident that demolition of several blocks of their respective

Figure 9.6

Older postwar population left on Howard Street in San Francisco's South of Market, 1953.

skid rows had permanently scattered their residents.[14] Enough vacancies still existed so that, indeed, most people displaced from the cheapest lodging houses could find some other place to live, probably at a higher proportion of their income or savings.

At middle-income levels, the national redefinition of old age brought other changes in the residential hotel market. Social security began to supplement retirement incomes in 1935. Fewer elderly men and women lived with their children, and people over sixty-five years of age began to create a new consumer market. Commercial care for the elderly and the supply of units in bona fide retirement communities improved markedly between 1940 and 1970, competing with yet another role played by midpriced hotels and rooming houses.[15]

A sudden influx of former mental hospital patients constituted a massive change for SRO tenancy. In the mid-1960s, the well-intentioned (and budget-cutting) decision of many states to mainstream mental hospital populations had been coupled with promises of half-way houses and group homes. Modern psychiatric medicines made this release possible. In California, the population of the state mental hos-

pitals declined from 37,000 to 7,000 between 1960 and 1973. However, the halfway houses were never established. Patients were essentially dumped into downtown hotels where neither hotel staff nor residents were prepared for the care required by these new neighbors. In conversation, tenants and managers alike often mention the arrival of publicly supported but inadequately served mental patients as the last blow to pleasant SRO life downtown. As one hotel owner put it, "Suddenly you weren't managing a building; you were running a nut house."[16]

In spite of all these shifts, not all residential hotels were dying. Through the 1960s, hotel rooms at every price range were a smaller but still surviving and viable housing market. A sizable population of healthy, usually single, and often elderly people still lived downtown in hotels and chose that style of housing. By the late 1960s, the formerly ample supplies of lodging house rooms were filling up. In the cheapest hotels that remained open in 1970, the arrival of new desperate tenants and the departure of the better tenants (for better hotels, apartments, or suburban life) left thousands of hotels packed with what one social worker in the mid-1970s described as "a human residue of the elderly and poor."[17] Ironically, the market-driven declines in hotel life were largely intended and carefully planned as part of the official rebuilding of downtown.

Official Prohibitions of Hotel Life, 1930–1970

While some urban changes informally influenced hotel residents, other changes—most of them officially devised within various phases of urban renewal—aimed directly at the eradication of hotel life. Urban renewal accomplished many important things, but it also deservedly earned many critics. In most cities, renewal was racially biased; renewal often lined certain landholders' or contractors' pockets more than it should have; building the new downtown frequently became an exercise in personal empire building at the service of the downtown business elite. Urban renewal was also a period of hotel resident removal. Hotel housing was absolutely foreign to the aims and legal limitations of public housing. During the decades of urban renewal, officials moved from making antihotel policy to attempting to eliminate hotels; this prohibition was part of their scheme to end all urban blight and poor housing.

The assumptions behind the planned elimination of residential hotels seem to have been very much like the notions behind the national Volstead Act and its attempt to eliminate all alcoholic beverages. Prohibitionists assumed that if they took away the supply of a mistrusted part of the material culture, then the use and need would end as well. Just as the stubborn public refusal to give up drinking hindered the intended social benefits of the Volstead Act, so too the continued existence of hotels seemed to block the promise of the new city. These policies provided major fuel for the later SRO crisis.

Definitions of Blight as Condemnation

The rebuilding programs that preceded full-scale urban renewal were of modest scale. During the New Deal, demolition was typically done lot by lot in keeping with the federal policy of equivalent elimination. The idea was to remove slum housing at exactly the same rate that public replacement housing was built. For each new public housing unit completed, a dilapidated housing unit elsewhere had to be condemned, repaired, or demolished.[18] Ironically, hotels escaped early public demolition because only accepted housing units (those with private kitchens and baths) could be considered for equivalent elimination.

The idea of blight, however, helped post-World War II planners do wholesale bulldozing of U.S. hotel stock. The concept of blight (as opposed to the concept of a slum) summed up the officially perceived problems of the old city. Hoover's 1932 Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership defined a slum as an area of social liability; that same area, the panel concluded, might continue to be profitable for its owners. A blighted area, however, was an economic liability—a district whose property values were so depreciated that they returned less in taxes than they cost in public services. By the late 1930s, downtown landowners were particularly concerned about depressed property values in hotel areas. Politicians worried about such zones because of their reduced tax revenues and high costs of services. The Hoover conference's committee on city planning and zoning used cheap hotels and mixed uses as their prime examples of neighborhood blight.[19]

The 1945 law that enabled urban renewal in California required that blight be demonstrated before clearance, and it gave a multipage definition that planners summarized as follows:

[Blighted areas are] areas compactly built . . . with indiscriminate mixtures of industry, business, and housing, having large percentages of substandard dwellings and absentee ownership, lacking adequate open spaces, play grounds, and gardens, and presenting ugly, depressing vistas on the public streets.[20]

Greenery and designerly vistas were to be preferred over any old city social values.

During the New Deal, the areal extent of blight had been detailed by real estate experts working on real property surveys. In San Francisco's survey, completed in 1939, the majority of substandard dwellings were so classified because they contained shared toilets or baths. Forty percent of the Western Addition's population (50,000 out of 86,000) shared baths or kitchens with other households. In a 1935 survey, 80 percent of the Western Addition's units had been found in good repair. Thus, dilapidation was not generally a problem. However, by 1946, the cost of police service to the area was reported to be ninety times that of newer middle-income areas.[21] In the official maps of blighted areas, different sorts of hotels fared differently. In 1939 and 1945, the mid-priced hotels and better rooming houses of the Tenderloin area were not marked; these postfire structures were of masonry construction, had good plumbing, and were still profitable. For the same reasons, the two blocks directly south of Market Street also fared well. The blocks of the waterfront, Chinatown, the Mission district, and South of Market—with many wooden buildings and far more mixed uses—fared worse (fig. 9.7). Predictably, blight and proposed condemnations were thickest in the Western Addition.

In 1945, the federal bulldozer was not yet at the door in San Francisco, but it was on its way for the vast majority of SRO rooms. "No amount of enforcement can change blighted neighborhoods," wrote one planner about San Francisco after World War II. He continued, "Nothing short of a clean sweep and a new start can make the district a genuinely good place in which to live."[22]

Nonbuilding as Eradication

The clean sweep of hotels came not only with the tearing down of former single-room districts but also with the decisions about what types of buildings should fill the empty

Figure 9.7

Reformer's-eye view of rooming houses in San Francisco, 1947. One local

newspaper published this picture, which shows the back of the structure,

with the caption, "Exterior of typical Western Addition Rooming House."

The house was four blocks from City Hall.

blocks. That is, the official prohibition of hotels entailed both clearance and nonbuilding , active refusal to build, repair, or subsidize residential hotels with public funds. Publicly funded housing of World War I and World War II had included hotels and dormitories, although for the most part these were temporary structures. Nonbuilding had become officially ordained with the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration during the New Deal. Through the 1970s, the federal government funded or assisted virtually no hotel-style public housing other than college dormitories and too few studio apartments that might have replaced midpriced hotel housing.[23]

In concert with federal policy (which in turn was tied to federal funding), local bureaucracies in charge of rebuilding downtown usually had to avoid the construction of hotel housing. San Francisco established its city housing authority in 1938, and its foremost priority was to build suburban-style apartments for urban families—putting the idealist strategy into concrete. The authority's first three projects were three-story walk-up garden apartment buildings set in ample open space.[24] After the war, in 1945, came the time for larger-scale work. As experts were doing in other states, California city officials convinced the legislature to give special city authorities the power for complete urban renewal: designating blighted areas, replanning and replatting the blocks, and (unlike the New Deal scheme of public construction and management) then selling the land to private developers.[25]

Figure 9.8

Map of an urban renewal study area, drawn to emphasize the density of San Francisco's inner

Western Addition, 1945. From a report of the City Planning Commission.

San Francisco's first clearance under the new rules was to be in the Western Addition; it was to be a total redevelopment initially slated for 280 city blocks. In a widely circulated 1947 report commissioned by the city Board of Supervisors, planners and architects developed a detailed plan for a study section nearest the civic center and downtown (figs. 9.8, 9.9). At the time, the Western Addition clearance was correctly criticized as "Negro removal," but the project was also hotel housing removal. In 1947, the planners still assumed a single developer would rebuild the study area. The staff, the planning commission, the supervisors, and the mayor agreed that the neighborhood demographics were to remain the same. Out of 445 hotel units existing in the area, the experts liberally proposed to keep 200. Yet out of the 3,799 new housing units they proposed to build, none were hotel units. Of the households throughout the Western Addition, 36 percent were to continue to consist of one person, with a much higher proportion of single households in the blocks close to downtown, like the study district. Thus, the sample area plan called for 56 percent of the new units (2,139 out of 3,799) to be two-room efficiency apartments consisting of a sleeping-studio room, an adjoining kitchen-dining room, and a bath-

Figure 9.9

Proposal for the inner Western Addition, suggesting removal

of the old housing and replacement with single-use public

housing towers. San Francisco City Hall is in the foreground.

Figure 9.10

An idealistic SRO upgrade proposal, 1947. As rooming houses

were torn down, efficiency apartments like these were

originally envisioned for the rebuilt Western Addition.

Figure 9.11

Apartment towers proposed for the Western Addition, 1947. The eight

upper floors were to be efficiency apartments that would replace

rooming house units. At the lowest level were two-story town

house units for larger households.

room (figs. 9.10, 9.11).[26] This very liberal proposal was in effect an idealistic SRO upgrade.

The 1947 proposal was part of a strategy to establish the city's redevelopment agency, which was founded in 1948. Mayors hostile to renewal prevented the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency (SFRA) from acting in any significant way from 1952 until 1959.[27] During the seven-year hiatus, changes at both the local and federal levels meant that the idealistic scheme for rehousing of the Western Addition's residents was largely lost. By the 1960s, the urban renewal plan for the district was very different. For market rate housing, the mix of unit types was left to the discretion of individual developers. For housing

with public subsidies, the programs themselves usually dictated larger units for larger families; heavy-handed administrative pressure from Washington also pushed the mix toward one- and two-bedroom units and away from studio units. For the first phase of redevelopment, data from 1971 show that only 16 percent of the units were studios or efficiencies—in a city where over half of the people waiting for public housing were single elderly people who needed small units. In the second phase, the SFRA's own study found that more than 4,000 of the displaced households (61% of all households) were single-person and more than half, nonwhite. Data on apartment-size mixtures are strangely not available for this phase of the redevelopment, but the proportion of studio units was probably less than 16 percent. Meanwhile, deliberate ignorance continued unabated. A thorough 1967 interagency report on San Francisco's housing did not mention SRO or other hotel units in the city.[28]

Other proposals were more radical than the 1947 San Francisco proposal and even less successful in gaining either local or federal approval. An earlier proposal, one which probably inspired the San Francisco planners, was made during the New Deal by Harvard professor James Ford. For New York City he suggested huge new SRO replacement hotels within larger housing projects. Ford was concerned not only for single people in existing hotels but also for the estimated 200,000 lodgers who lived with New York families. Ford argued that if proper quarters were available for the lodgers, then they would not crowd into the new family housing. For potential housing sites both on the Lower East Side and in Harlem, he recommended interspersing tenstory elevator buildings for family housing with similarly scaled SRO buildings. According to his scheme, some of the SRO structures would have been segregated by gender; others were to accommodate men and women on separate floors; still others would have contained small efficiency apartments in addition to single rooms. He also advocated rehabilitating New York's existing rooming houses. Even in the heady days of New Deal experimentation, however, Ford's ideas had been flatly rejected.[29]

In 1952–53, Catherine Bauer and Davis McEntire proposed that the Redevelopment Authority of Sacramento build an entirely new SRO workers' district at a new location to clear the city's West End skid row for more upscale uses. To house the state's largest agricultural

labor pool, Bauer and McEntire suggested 3,000 cubicle rooms of relatively permanent occupancy and 1,500 dormitory beds for migrants, all built above commercial spaces, all to be owned by the city and leased to private managers. At the going rates of 75 cents per night and $7 per week, the project would have been largely self-supporting. Bauer and McEntire admitted they were up against extant federal policies, especially Section 207 of the National Housing Act (which recognized only rental units "of design and size suitable for family living"). Sacramento's redevelopment agency actually concurred with the plans, and several private developers were interested in Bauer and McEntire's proposal. However, the difficulties of finding cheap land and the lack of appropriate federal programs killed the brave project.[30]

The proposals for San Francisco's Western Addition, Ford's SROs in New York, and Sacramento's West End were exceptions in the general tide of urban renewal ideas but not rarities. Their existence proves that at least some local leaders and housing designers saw the continued need for and viability of hotel housing, or something very close to it. Yet, the official nonbuilding policy for hotel projects, especially after the mid-1950s, reveals how monolithic housing policies were. The vast majority of public housing proposals gave only lip service to oneperson households, in large part because needs for larger households were equally or more pressing, politically more visible, and keyed into the doctrinaire single focus on the family. While public programs avoided building new hotel units, parallel actions by many of the same agencies were destroying existing residential hotels.

Making Tenants Invisible

As with the SFRA's applications of blight and nonbuilding, the actions of other hotel-closing agencies were not (in their own minds) aiming the wrecking ball at the homes of the poor but "eliminating dead tissue," "applying the scalpel," "clearing away the mistakes of the past," and building "an attractive new city." About a Norfolk, Virginia, hotel district, one planning journal editor reported in 1961 that "progress had reached the demolition stage." Local agents crowed that they had "reduced to rubble . . . scores of flophouses not renowned for adding luster to their city's good name."[31]

Because officials did not consider hotels to be permanent housing, during the official massive downtown clearances from 1950 to 1970, people living in hotels were not tallied as residents. Hence, when a

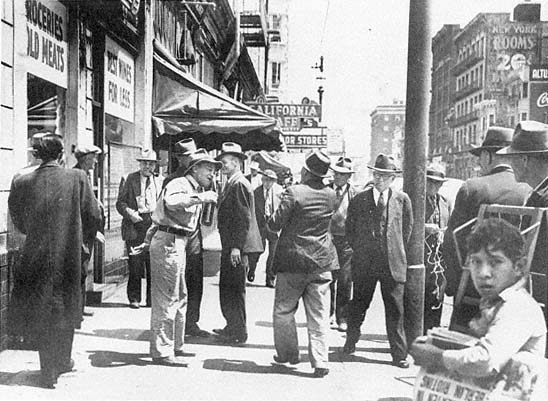

Figure 9.12

Helping to make skid row residents look bad, 1956. This picture

of a bottle club in the South of Market was carefully posed

by a San Francisco newspaper photographer. Fostering

such stereotypes lessened concern about SRO demolition.

city demolished an SRO building, "no one" had been moved, and no dwelling units were lost in the official counts and newspaper reports (fig. 9.12). In reality, of course, hundreds of thousands of SRO people and homes were being removed. Deliberate ignorance had become a cultural blind spot that made hotel residents invisible both to officials and to the public. A 1970 planning study in San Diego found only 100 people living in the city's large single workers' district, which was being considered for demolition. Local hotel housing advocates protested. A second count in 1975 found 499 people in the same district; after another protest, a third count found 1,000 hotel people still living in the district—and this after several hotels had closed because of the official pressure. In some cities, the people removed were difficult residents: bums, psychotics, or other marginal people. But the vast majority were not marginal. By making them invisible, experts made the rough handling of such people easier.[32]

Relocation costs gave city officials another reason to make hotel residents invisible. The 1961 Housing Act provided up to $200 for a family displaced by renewal but gave no guidelines and granted no federal funding for single individuals. To fill that gap in the law, the Urban

Renewal Administration in Washington authorized local authorities to pay each single SRO person a relocation fee of $5, approximately cab fare out of the neighborhood. "Transients," those who had lived fewer than ninety days at a hotel, did not even qualify for the $5, although many local agencies paid the token relocation fee to any SRO tenant who applied.[33]

In San Francisco's redevelopment of the South of Market, politicians and downtown leaders deemed a large clearance was necessary for what eventually has become the huge Moscone Convention Center and its adjacent Yerba Buena Gardens. In the blocks to be cleared during the 1960s, 91 percent of the households were single, and most were white; 97 percent lived in hotels. A surprising 41 percent of the 240 families in the renewal area also lived in hotels. Later studies estimated that about 40,000 hotel rooms were destroyed, although city officials kept no tally.

Initially in areas like the Western Addition and South of Market, the opposition of hotel residents was neither strong nor organized. Instead of fighting a seemingly impossible battle, tenants took their $5 relocation fee and moved. To their credit, the staff in many urban renewal agencies attempted to give SRO tenants help in finding a new home; in some cases, the appointed social workers made repeated visits and multiple notices. The SRO residents, tending to be fiercely independent and suspicious of authorities, usually had ample reason to mistrust overtures from urban renewal agents. In any case, up until the early 1960s the vast majority of the tenants moved on their own, without help. Long after the supply of inexpensive SRO housing had reached a critical stage, these tenants still thought they could find a new place.[34]

In the late 1960s, hotel tenants met increasing frustration in finding rooms. The losses in rooms had far outpaced the losses in clients. No national figures exist for the number of SRO hotel rooms destroyed before 1970; estimates usually refer to "millions" of rooms closed, converted, or torn down in major U.S. cities. Including the hotels closed in small towns and medium-sized cities would double the number of units lost.[35] Alarmed by the simmering political and health implications of relocation and the declining quality of life in inexpensive hotels, a few pioneering planners, social workers, public health officials, and journalists recognized the beginning of an SRO crisis.[36] During the 1960s, this new corps of SRO advocates began to chip away at the unfair

stereotypes about hotel life. Their work coincided with a growing professional and public disillusionment with downtown renewal. The publication of books such as The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961, The Urban Villagers in 1962, and The Federal Bulldozer in 1964 had galvanized critiques of urban renewal processes and goals.[37] Among housing officials and planners, the time was ready for a more widespread change of heart about hotel life. Unfortunately, for many hotel residents, this revised view would be too late.

Since 1970:

Conflicts Surrounding Hotel Life

Before 1970, the elimination of SRO units was encouraged by government policy, often against the objections of private hotel owners. Since 1970, hotel housing advocates have hammered together a pro-SRO movement and won converts in official life. Pro-SRO activists continue to be haunted by critics and by the underside of hotel life. Nevertheless, since 1970, officials and owners have changed sides. Growing numbers of public officials have moved to conserve hotels, while more owners want to close or raze their buildings. The following summaries can introduce only salient moments and principal themes in the gradual building of a national pro-SRO movement after 1970. Not presented here—but available in the cited literature—are the complex historical processes which supported and delayed each case: urban and regional economies, local power structures, and myriad participants. For each failed SRO campaign noted here, a great many more occurred. Other positive examples also exist, but in more modest numbers.

The Coalescing of a Pro-SRO Movement

Between 1967 and 1973, the political situation of hotel life changed dramatically. The climate of American political activism and awareness of minority needs had reached critical mass. As part of reforms aimed at urban renewal, arguments began to be heard locally and in Congress for the inclusion of hotel residents in public housing programs.[38] Responding to these arguments, Congress passed the Uniform Relocation Act in 1970. This policy change marked 1970 as a major pivot year in the political history of SROs. For the first time, redevelopment agencies and other federally funded groups were legally required to recognize people living in hotels as bona fide city residents; if a residential hotel was to be demol-

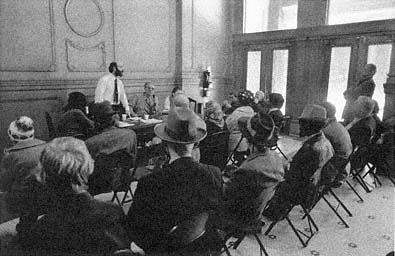

Figure 9.13

A hotel tenants' meeting in San Francisco's South of Market, 1973. Members

of Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment (TOOR) confer with

their lawyers in a hotel lobby.

ished as part of a public project, the agency had to help the hotel tenants find new housing, just as if they were apartment dwellers. Twenty years of official removal had made SRO units hard to find, and the process of assisting tenants was difficult. Most critically, the budget outlays were substantial: each hotel dweller was to receive the $200 household dislocation allowance, compensation for moving costs, and up to $83 a month for four years if the new housing cost more than 25 percent of the individual's income; the total was not to exceed $4,000.[39] Suddenly hotel residents were both visible and very expensive for the urban renewal process.

Simultaneously, SRO tenants had learned their rights and with community activists had organized themselves more effectively. Because urban renewal was early and done on a large scale in San Francisco, the local movement against it was an important national example. In 1968, South of Market hotel tenants began organized protests of the relocation for what became Moscone Convention Center and Yerba Buena Gardens (fig. 9.13). In December 1969, courts issued the first restraining order against the San Francisco Renewal Agency, and the court battles continued for four years. The residents proved to the court that adequate replacement housing did not exist in the city, and the court forced the SFRA to develop over 1,500 units of new housing in the area. Developed by a nonprofit community group, Tenants and Owners Development Corporation (TODCO), the first new replacement housing opened in 1979.[40]

San Francisco was only one early center among several engaged in full-fledged fights to revise plans for urban renewal and to save SROs. In Boston SRO tenants stopped progress on a renewal program. So did tenants in New York's Greenwich Village and on the Upper West Side. The New York Mayor's Office of SRO Housing was opened in 1973 to work on social programs and tenant protection laws. Other groups were working to rehabilitate hotels and improve their management. In 1975, a pro-SRO group in New York City, Project FIND, leased and moved into the 308-room Woodstock Hotel, located near Times Square.[41] These projects saved only a few hotels from demolition but did create a new and embarrassing climate of public relations. Suddenly hotel owners, city housing authorities, redevelopment agencies, and other people with anti-SRO views had to work hard to prove that residential hotels were an urban blight of culturally aberrant buildings where only marginal people lived.

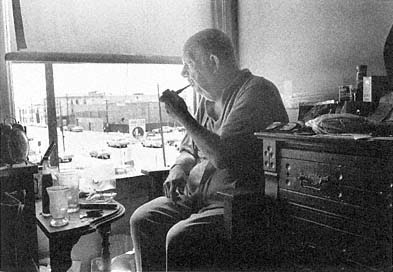

Unfortunately, the Uniform Relocation Act could not decree an instant change in the SRO attitudes of all housing officials in Washington, D.C., or in local agencies; at first, the act exacerbated harassment of residents and hastened hotel demolition. From 1970 to 1980, an estimated one million residential hotel rooms were converted or destroyed, including most of the Yerba Buena area (fig. 9.14).[42] Hotel owners generally did not want help to stay in business, in large part because of the potential profits from the expansion of downtown offices. In the 1970s, downtown office construction suddenly started a new boom and developers began to offer hotel owners handsome prices for their properties. Then, as now, the land underneath most residential hotels had more market value than the buildings. In New York, an empty hotel was worth two to three times that of an occupied building because the new speculator owner could more quickly rehabilitate it for a new use or tear it down.[43] Then, as now, to encourage the perception of hotels as blight, public and private owners understated the positive side of hotel living and overemphasized the problems in bad hotels. In day-to-day management and long-term goals, the lines between public and private ownership often blurred. Redevelopment agencies (through eminent domain) and city governments (through tax foreclosure) frequently became unwilling landlords for remaining residential hotels. To manage their hotel programs, they often hired anti-SRO people from the property industry, not pro-SRO people from social welfare offices.

Figure 9.14

Ken Roth, a South of Market hotel resident in the 1970s, watching the

demolition of his San Francisco neighborhood for the Yerba Buena project.

For the stubbornly positive SRO buildings with sound structures and tenants neither marginal nor easy to dislodge, both public and private landlords developed an arsenal of tools to create problems where none have existed before. Although the techniques were perfected in the early 1970s, many remain in use. To generate vacancies, one of the most effective means was to reverse normal management principles and to harass the tenants: replacing friendly, long-term staff with churlish employees; suddenly lowering the standards for admissible tenants; and loosening security, stopping maid service, or permanently removing clean linen from stock. Other owners deliberately aggravated tenants by shutting off heat and hot water for long periods, locking toilet rooms, not repairing (or entirely closing down) elevators in six-story and eight-story buildings, plugging room locks, seeing that mail and messages were "lost" (particularly for tenants who were demanding their rights), not letting Meals on Wheels attendants deliver food, spraying for roaches while tenants were still in the room, taking the furniture out of the lobby, falsely advertising no vacancy so the hotel emptied, and sending gangs of thugs along with eviction notices to intimidate tenants. The agents of one hapless San Francisco hotel owner had the poor judgment to use the roach-spray-in-an-occupied-room technique while one of Mayor Dianne Feinstein's aides was visiting the tenant. One New York landlord went at the steel stair landings of his building with a hammer and chisel; after five flights of stairs had thus

"collapsed," the building had to be vacated because of failure to comply with fire safety laws.[44]

In San Francisco, struggles like these eventually led to the International Hotel dispute and eviction of 1977, which was another turning point in national opinion about SRO homes and SRO people. After eight years of nationally publicized eviction struggles, at 3:00 A.M., 330 police officers and sheriff's deputies converged on the hotel, which stood at the edge of Chinatown. After vociferously protesting the court orders to do so, the sheriff had finally come to evict about forty elderly Chinese and Filipino residents who remained in the 184-room hotel. On nearby sidewalks more than 2,000 demonstrators protested. Many of the public knew the hotel's location not only because of its residents but also because of its large basement nightclub, the hungry i, which in earlier years had headlined Barbra Streisand, the Kingston Trio, Dick Cavett, Bill Cosby, Dick Gregory, and Woody Allen.[45] After the eviction battle, the owner of the property, the Four Winds Corporation of Singapore, immediately razed the building. Fifteen years later, the site was still empty, except for the archways of the remaining basement walls, where the hungry i had once been. There, on cold nights, homeless people huddled to get out of the wind.

The tenants in the International Hotel lost their single-room homes, but like tenants in earlier cases, their fight helped to raise new questions about the intersections of hotel life, property rights, and social services. For instance, the year following the eviction, the staff of the U.S. Senate used the case for the introductory example in an information paper about the SRO crisis.[46] Owing to the fights of the 1970s, the formerly invisible realms of hotel life finally began to appear regularly in public spotlights, with front-page newspaper articles headlined "Rooms of Death," "Heatless Hotels," and "Struggle over Downtown Continues." Through the 1980s, the New York Times prominently featured SRO stories nearly once a week. The Gray Panthers and other senior groups also came to be instrumental in several fights.[47]

Another important example of the turnaround process since the 1970s is the experience of Portland, Oregon. About the same time as the last fights at the International Hotel, a private group remodeled Portland's Estate Hotel with a city loan; in 1978, neighborhood leaders formed the nonprofit Burnside Consortium (now called Central City Concern) to coordinate services and to preserve other housing. In 1979,

Andy Raubeson was appointed director of the consortium and saw immediately that SRO hotels were a prime priority for his skid row clientele. "It just seemed too obvious," he says, "that we had to champion the housing stock." His organization began leasing and then buying hotels, eventually renovating more than five hundred units.[48] The Burnside experience emphasizes the growing realization that proper management—often subsidized by a nonprofit organization—is a key to maintaining low-cost hotel life. As part of the Portland action, in 1980, U.S. Rep. Les AuCoin, a Democrat from Oregon, persuaded Congress to make SROs eligible for federal low-interest rehabilitation loans and then for Section 8 housing funds. These and other successful programs have put Portland in the forefront of municipal efforts to preserve SROs.[49]

With the federal Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1981 and the Stewart B. McKinney Bill in 1987, hotel housing moved further toward better housing status and became eligible for a few other subsidies. With cruel irony, these official changes of heart began just before the Reagan and Bush administrations slashed public housing funds by 80 percent.[50] The widespread implementation of the new policies was thus deferred.

The Legacy of Problem Hotels

In spite of a generation of pro-SRO work and the gradual but growing official acceptance of hotel life, the problems of the past continue to haunt the progress of the present. At the worst hotels, not only the buildings are residues. So are the owners and managers. For many owners, a net loss helps their tax accounting. Such owners are unwilling to put money into their buildings; they hire the cheapest possible managers, who rarely have any training and never stay very long in the demanding and often dangerous business. Many managers lack the simple bookkeeping acumen to maintain profitable cash flows. Observers in Portland saw hotels where repair investments as small as $15 per room (for fixing a broken sink, window, or toilet) could have restored one-fifth of the vacant rooms to full weekly and monthly rents. For other managers, costs of labor and of maintaining desk, telephone, linen, and housekeeping services have risen at a rate greater than reasonable rents.[51]

The most deteriorated rooms and disturbing social conditions in hotel life do not necessarily occur in the cheapest hotels but in those

where managers and owners are completely callous, inept, underpaid, or overwhelmed. Most simply, these locations can be called "problem hotels." A subset of problem hotels are those where the owners and managers have given up any attempt at lobby surveillance and where no one screens or controls troublesome residents, guests, or behavior. Social workers call such places "street hotels" or "open hotels."[52] The daily conditions around problem and street hotels disturb even SRO advocates. In a street hotel, the negative stereotypes of hotel tenants ring true: a majority are unemployed, addicted to alcohol or narcotics, mentally ill, or otherwise chronically disabled. The tenants exhibit little capacity for normal social life or collective political action. Single parents may leave children unattended for long periods. The residents might include someone who likes to throw knives at walls or a heavy drinker who routinely vomits on the hall carpets or urinates in the elevators. In street hotels, lobbies and halls are unsafe because speed freaks attract or bring "bad trade" into the building. The desk clerks do nothing to screen out these people. Other tenants collect stolen weapons or other contraband items in their rooms. The more vulnerable tenants are often brutally beaten and robbed by the tougher ones. Tenants in problem hotels expect to see psychotic behavior or erratic anger.

Safety and health hazards also darken life in problem hotels. Children fall to their deaths from unprotected windows or open elevator shafts. Uncollected garbage piles up in the halls; rats jump from can to can. Some residents hoard toilet paper; then because no toilet paper is available, other residents substitute newspaper, which clogs the toilets. Because the maintenance staff is minimal at best, the toilets can remain out of commission for a long time. Eventually, when angry tenants break toilets with baseball bats and angry landlords refuse to replace the shattered plumbing, even those not incapacitated by alcohol use the halls for toilet rooms.

The fire hazards of problem hotels match their social and health risks. Fire escapes may be wooden; panic hardware is absent on the doors; no alarm system has ever been installed, or the aging system is out of order. Smoking in bed causes frequent mattress fires. Tenants (or landlords) intentionally set other fires. Because the electrical wiring in the rooms is old and intended to run only one 60-watt bulb, overloaded extension cords to refrigerators and hot plates routinely blow fuses or

start fires. Managers and tenants put out the fires by themselves if they can; if they call the fire department, fire marshals may inspect and then close the building.

The people and activities from these problem SRO buildings spill out into the surrounding neighborhoods. Socially marginal residents and their friends congregate outside the door. They panhandle passing pedestrians, or rant to them about imaginary fears. Garbage (called "air-mail" by hotel residents), epithets, and urine can be hurled from open windows onto surrounding sidewalks.[53] New York's Hotel Martinique, made infamous by Jonathan Kozal's study Rachel and Her Children , exemplified many problem hotel dimensions of the mid–1980s. Kozol detailed a case in which crowding, lack of services, and corruption had created a nightmare for family groups. The supply of the city's public housing apartment units and affordable apartments had lagged so far behind need that social workers were forced to dump clients on a temporary basis that was essentially permanent and very expensive for the public. Dangers and privations endured by single people and by the elderly in problem hotels can be equally serious, and are often similarly intertwined with public assistance.

Problem motels for permanent residents have begun to reflect the degree to which the American city has become a suburban city. Where highway traffic has shifted away from a motel and the units are over a generation old, managers have hung out signs advertising WEEKLY AND MONTHLY RATES. At the more expensive examples are salesmen on temporary assignment and construction workers in town for a season. There, the system works. Elsewhere, residential motels often shelter very low income residents. Families unable to afford other housing and recent immigrants sometimes fill whole motels that have the worst management. Many of the families, like those in light housekeeping rooms in the 1920s, have their furniture in storage. In 1985, officials estimated that Orange County, California, had 15,000 people living in motels, along boulevards such as Katella Avenue near Disneyland. South of San Francisco, hundreds of families and single-person households live in residential motels that line access roads to the Bayshore Freeway not far from the airport. The Memphis, Tennessee, motel where the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed in 1969 had become a residential motel and a haunt of prostitutes by 1988, when residents were evicted to convert the structure into a museum of the

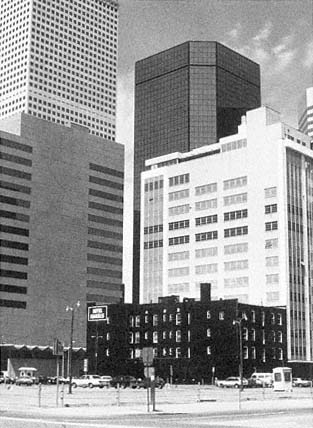

Figure 9.15

A three-story rooming house, the Hotel Harris, virtually

quivering before the onslaught of new office tower

development in Denver, 1983.

civil rights movement. Even the wealthiest counties can have serious residential motel problems. The citizens of Westchester County, north of New York City, refuse to build adequate low-income housing but pay $3,000 per month for each of hundreds of residents in miserable motels where the maids steal medications and a reputed 80 percent of the residents use crack cocaine. Often without cars, parents cannot reach jobs or take their children to school.[54]

Many of the eradication processes that destroyed good hotel homes in the 1960s and 1970s have remained in force (fig. 9.15). Through the 1980s, professional "housers" or housing activists were typically not converted to pro-SRO views. Cushing Dolbeare, long-term director of the National Low Income Housing Coalition in Washington, D.C., admits that people like herself were the hardest to convince. She notes that housers "assumed that the requirement for a kitchen and a bath for each unit was always supposed to be in a housing proposal." She was

not personally involved in the pro-SRO movement until 1981.[55] Some housing advocates still expect that preserving hotel housing will undermine family housing minimums and that the cities will not have the ability to enforce occupancy standards of one or two people per room even for elderly people. All hotel rooms, the doubters say, will soon be overcrowded with single mothers with three children each. In 1985, when many people could only choose between living on the street or in an armory shelter, a HUD program director still stated that in rehabbed structures "asking people to give up a private bathroom is an awful lot."[56]

Official actions continue to reverse earlier progress. In 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court eviscerated New York City's 1985 moratorium on SRO conversion or demolition, although rent stabilization laws continued to protect most of the city's long-term tenants. In California, for more than twelve months after the Santa Cruz and San Francisco Loma Prieta earthquake in October 1989, planners and hotel residents of several cities had long struggles with officials of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) over whether or not residential hotels qualified as dwellings for more than $50 million in repair or replacement funds.[57] The debate sounded a great deal like the debates of the 1960s. "The wave of the future may be an undertow," warns SRO activist Richard Livingston. "For each hundred hotel units that we fight to save, a thousand are torn down or converted. We are moving rapidly backwards."[58]

The problems of living at the lowest-priced hotels are serious, but many of them are inherited from generations of misunderstanding. Prohibition, the national ban on alcoholic beverages lasted only thirteen years. The national prohibition of single-room housing lasted more than sixty years and is not yet completely rescinded. Many public officials have come to realize the importance of SROs at precisely the same time that their redevelopment agency has just torn down the city's last publicly owned—and usually largest—SRO buildings.

Nonetheless, shifting policies and programs in several cities show a viability for hotel life and suggest that public vision is widening. Hotels remain the cheapest private housing available downtown. Hotels are less ideal than apartments, especially for families with young children. However, as numerous activists put it, for the most difficult to house

people in the city, hotels work "better than shelters and better than the streets."[59] In bad hotels, a change of owners and better management can create a very different home environment, even for hotel and motel tenants with very low housing budgets. Where managers strictly control lobby entrances, carefully screen residents, and keep up building maintenance, the type of tenants and their living situations change dramatically. Managers at positive SROs still serve their tenants not only as tough-minded rent collectors and rule enforcers but also as social workers, part-time grandparents, or political advocates. Significantly, rents in successful SROs are not necessarily higher than in street hotels, although as the price rises, conditions generally improve. The profitability of a good residential hotel lies in higher occupancy rates with less turnover.[60]

For public housing provision, hotels make economic sense, too. As Bradford Paul has put it, for the cost of one new HUD Section 8 studio apartment, 4 or 5 hotel rooms can be rehabilitated in San Francisco (with its stringent seismic safety requirements); 12 to 15 rooms can be rehabilitated in Portland; or 35 to 40 rooms can be rehabilitated in city-owned hotels in New York.[61] Seeing figures like these, more and more elected officials and representatives have begun to join pro-SRO forces, spurred by the worsening homeless situation. More cities have passed and enforced ordinances to slow the conversion or demolition of residential hotels. Several mayors have created special offices for hotel housing and encouragements for rehabilitation. In the early 1980s, the New York mayor's office began offering six-month training courses (two nights a week) and internships for SRO managers.[62] These experiments in a new attitude about downtown hotel life, in addition to each one hundred hotel units that are saved, may have an importance far greater than their initial numbers. The wave of the future may be a wave of change.

The Prospect of Pluralism in Housing

The argument of this book is fairly straightforward. Public and professional housing attitudes—in particular, doctrinaire idealism and deliberate ignorance—have devastated an important supply of American urban housing. Between 1800 and 1960, hotel entrepreneurs and their clients and staffs developed both good and bad traditions of hotel life,

responding especially to the needs of urban employment. By the time of the Civil War, hotel life comprised four distinct downtown subcultures; hotel owners and their architects had unofficially but effectively begun to stratify environments to match those cultures. Simultaneously, housing officials began a one hundred-year campaign to write hotels out of public policy because hotel life undermined middle and upper class cultural ideals and hotel land-use mixtures threatened professional hopes for a new, specialized city. This cultural imperialism fueled the near-annihilation of hotel life. For over fifty years, until the beginning of the pro-SRO movement in the 1970s, public policymakers unnecessarily shelved the high-density housing option of hotel living as a tool of urban life and culture. The history of hotel living affirms that the built environment is not merely a result or a background for human action but a participant, a player in collective human life. The problems of doctrinaire idealism and deliberate ignorance continue to haunt present hotel life and United States housing plans.

Expanding the Notion of Home

The history of hotel life shows that the crisis in the residential hotel supply was a planned event. So too, solutions to the SRO crisis can be planned events choreographed by residents, activists, officials, owners, and experts. Pioneering groups have begun to build new residential hotels, thereby stretching the boundaries of both the official and public definitions of home in America.

The new residential hotel building types are as varied as their different sites and cities. For lower-income residents, hotel makers are reinventing the rooming house; higher-income residents are seeing variations on the midpriced hotel or motel. For new rooming houses, the trend is to plan fairly large buildings with at least one hundred rooms. Most typically, they are structures remodeled or built with some type of public/private partnership and managed by a nonprofit organization. However, with initial subsidies a few private developers have also successfully developed SRO projects. Because neighborhoods at the edges of town continue to block efforts to build for a diverse population, these hotels continue to be on expensive downtown land. Like the downtown rooming houses of 1910, the new rooming houses rely on commercial rentals on their ground floor to subsidize rents on the upper floors and to provide retail services for a neighborhood where home activities are scattered up and down the street. The new rooming

Figure 9.16

First floor plan for San Diego's Baltic Inn, opened in 1987. Rooms at the lower

part of the plan include the lobby, manager's apartment, and service spaces.

houses require larger lots to accommodate a comparatively large number of parking spaces—more than the 1910 rooming house, which had no parking spaces, and fewer than the typical present apartment requirement of one parking space per unit.

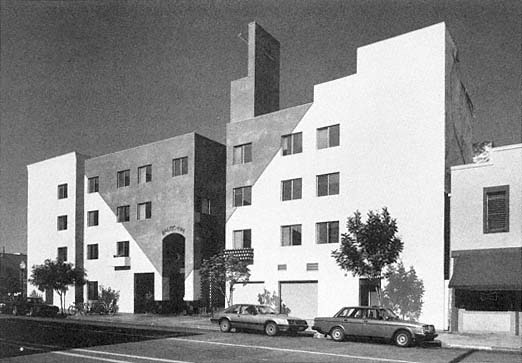

In the early 1990s, about a dozen of these projects in the United States are either newly built or in working drawings. Two West Coast examples are typical. In San Diego, California, the 207-room Baltic Inn opened in 1987. It was the first new SRO building in the city in seventy years and one of the first in the nation (figs. 9.16, 9.17). It marks a new least-expensive version of the rooming house. As one commentator characterized the legal permit battles for the hotel, "San Diego has said, in effect, that it is willing to permit some citizens to live in places most others would not prefer."[63] In Berkeley, California, the Studio Durant project has been planned for a large lot between the city's downtown retail district and the University of California campus. The 198 rooms occupy the upper three floors. At the back of the site (with an E-shaped plan of rooms above) is a large parking area; retail spaces and a generous lobby fill the site next to the sidewalk. The project features timely commercial facade design, as any good hotel owner would have re-

Figure 9.17

Street view of the new Baltic Inn, San Diego.

quired in the past (fig. 9.18). The projected construction cost in 1991, $20,000 a room, compares favorably with the $27,000 a room being spent to renovate a residential hotel across town.[64]

The most striking physical changes in these new rooming house buildings include their provision of more social spaces—lobbies, lounges, and shared kitchens—and their improved ratio of baths to rooms. The one to six ratio from 1910 is no longer viable. The Baltic Inn provides the new minimum: a private toilet for each room, simply in a stall behind a curtain, and a room sink on a small all-purpose countertop area. Showers are down the hall. The plan for the Studio Durant, geared to a slightly higher rent, provides each very small room with a private shower and toilet room and a room sink on a longer all-purpose counter built as a cooking area (with a small refrigerator and a microwave oven as standard equipment). The bathroom sink doubling as the kitchen sink harks back to light housekeeping rooms of the 1940s. The tiny built-in kitchen area, which has yet to gain a name, does not make these new dwellings into full studio apartments; in most cases these structures are not designed to meet apartment building codes. Instead, the better plumbing and wiring, the rudimentary baths and cooking

Figure 9.18

Perspective view of the Studio Durant, a new rooming house planned for downtown Berkeley, California.

The architect, David Baker, expresses each of the functional elements on the facade of the project.

units, are responses to age-old demands from both hotel residents and managers. In the past, because the wiring was not adequate, the smells disturbed neighbors, or the food attracted vermin, managers even in palace and midpriced hotels fought tenants who illegally cooked in their rooms. However, the small inexpensive refrigerator has revolutionized food storage. Milk bottles set to keep cool overnight on rooming house window ledges are no longer a telltale sign of residents making breakfasts in their rooms, and vermin can be made less prevalent as well. Making the wiring, plumbing, and cabinetwork more adequate from the beginning is better for both tenants and managers. The increase in bath ratio is completely in keeping with the history of increasing plumbing expectations in dwellings of all sorts in the United States.

Sustaining existing residential hotel buildings continues to be essential and even more challenging than constructing new buildings. Because very few purpose-built rooming houses were constructed after the early 1920s, 99 percent of the inexpensive hotel rooms in the United States are in structures that are seventy years old or more. Their heating systems and elevators wore out long ago, and most have been inexpertly patched and repaired rather than replaced. If the buildings have

any cooling system at all, it probably consists of those few windows that still operate. The plumbing is as old as the heating; the plumbing ratio usually needs to be improved, at least to one bath for each four rooms. All this refitting has to be done inexpensively and if possible without closing the building entirely. In 1990, using Community Redevelopment Agency funds, advocates in Los Angeles opened 520 newly rehabilitated SRO rooms on skid row and planned to build a new 72-room hotel. The sponsors argue that these SRO services will cost the city $11 a night versus the $28 per night for ward-style shelters. San Francisco has bought and renovated six hotels (with a total of 460 rooms) and turned them over to nonprofit agencies for management. In 1991, the city's Redevelopment Agency—the former archenemy of residential hotels—remodeled a downtown building as mixed apartments and SRO units. The unsung heroes of the hotel housing movement include the architects, managers, and financial backers who devise ways to upgrade structures like these.

Rehabilitated structures provide the widest variation in size and social program. Sheltered dwellings, small board-and-care homes, and halfway houses have made use of modest structures in a variety of settings, even in outlying single-family neighborhoods. In the 1990s, market rents marginally sustain thousands of 30-room downtown rooming houses, anonymous three-story buildings on 25-foot-wide lots often managed by families of recent immigrants. With appropriate subsidies for maintenance, these structures can continue to provide housing, probably at the upper end of the SRO price range. Midsized buildings, from 30 to 80 rooms, are more expensive to buy and manage; most hotel activists say that roughly 100 rooms are needed to make efficient use of a full-time manager and to staff a desk 24 hours a day. The scale of a 100- to 150-room older structure is also well matched to the financial abilities of many nonprofit organizations. The largest inexpensive hotels—those with 400 rooms—often require different sorts of organizations or partnerships for purchase, rehabilitation, and management.

Hotels that fewer people want to talk about are new or rebuilt temporary shelters for people living on the streets or in their cars. These structures may have to be the future equivalents of the lodging house rank—the dormitories, cubicles, and missions from the Progressive Era. They could replace the hastily converted armories, church base-

ments, barely renovated flophouses, and other temporary shelters that have become quasi-permanent while the SRO crisis has intensified. As temporary shelters or as permanent single-room housing, hotels cannot solve the entire housing crisis. But they can help to solve parts of it, especially for single men and women (even some with children) who need to get off the streets, for single working people with low incomes, and for low-income elderly people.

A possible revival is apparent for hotels at more expensive levels, too. Private developers in Quincy, Massachusetts, opened a new sixteenunit rooming house in 1986, the first purpose-built rooming house constructed in the Boston area in several decades. All over the United States, both public and private developers have reinvented the role of the midpriced hotel in the form of elderly housing developments with household services and common meals. In 1990, one typical Bay Area "retirement hotel" offered a private room, full hotel services, and meals for $1,500 a month and shared rooms for $650 a month. Chains of Hometels and Embassy Suites have begun to combine motel, hotel, and residential hotel features. For rents of $2,000 a month (without meals), expensive new apartment hotels—including a 44-story example in Chicago—essentially re-create the apartment hotel of the early 1900s.[65] The popular television series "Beverly Hills 90210" featured a teenage hotel child for much of the first season. According to the show's writers, the character of Dylan McKay "was supposed to live in the Beverly Wilshire, like Warren Beatty." Dylan is the Eloise of the Plaza for the 1990s.[66]

New and rehabilitated hotel buildings are only one of the new experimental residential structures that promoters are proposing to the American public. Not since the 1890s have so many new types of units, mixtures of uses, and shared facilities been tried simultaneously in the United States. Live-work (loft) structures, "mingles" (apartments designed to be shared or co-owned by two separate heads of household), co-housing (a cluster of separate houses that share cooking, recreation, child care, and open space), and "doubling up" (two households sharing one house to counteract high rents) are examples of a sudden burst of chosen or forced experimentation.[67] These projects, along with hotels, can reasonably be expected to push into more suburban settings as well.

These experiments continue to spark heated debates and are usually slow to gain official permission. Housing activists repeatedly must climb against a hundred-year-old glacial accumulation of skewed textbooks, laws, bureaucracies, and attendant attitudes. Two years or more can easily go by while the sponsors of a new rooming house debate with their financiers, the local planning office, the zoning commission, and finally the city council over procedural questions and definitions, including: Should each room in the rooming house be required to have a separate off-street parking space? Are these units legally apartments? If they are not apartments, what are they? If the minimum permitted room size is relaxed, what happens in the future? How will the management guarantee that future densities will not soon overwhelm provisions geared to one- or two-person households?

Obviously, funding subsidies are a prerequisite for most hotel housing projects at the lodging house or rooming house level. Public funds for construction and rebuilding of hotel housing are urgent, and they are needed in far larger amounts than ever before spent for alternative housing projects in the United States. Taxpayers who balk at these expenditures must be consistently reminded that, according to one analysis, the 1990s home owner deduction from federal income taxes has amounted each year to a $47 billion subsidy for private suburban households, half with incomes over $80,000 a year. This private home owner deduction equals four times the entire annual budget of the Department of Housing and Urban Development.[68] If the economically comfortable can be so handsomely subsidized, in good times as well as bad, then the economically essential—the poorly paid people or elderly people who have played fundamental roles in our economy but at low-paying jobs—equally deserve subsidy.

Along with funds for construction, new programs must be funded for management training, building on the New York City model. Running a hotel was one of the most demanding jobs of the nineteenth century, and it is still a task that requires more than can be learned on the job. The horrors of past and present street hotels and indifferently managed flophouses have repeatedly proved that management is as important as the building itself for successful hotel housing. The current cadre of nonprofit hotel staff cannot stretch to cover the number of improved hotels that are needed in the near future.

The necessity of hotel housing is not decreasing. All indications from those who know the homeless situation point in one direction: the need for inexpensive, nonapartment housing is only going to increase. Alice Callaghan, from the Skid Row Housing Trust of Los Angeles, noted in 1992 that hotels were still the last place available for urban people. Like so many other SRO activists, she stressed that hotels provide the last viable safety net for housing; if people miss this net, they will either become homeless—literally forced to live on the street—or institutionalized.[69] It is significant and a sign of wider public concern that Callaghan was being interviewed for an airline flight magazine. In 1970, her only audience might have been the readers of a social welfare journal. Even a relatively conservative housing expert can now publicly point to the unattached as being the least well-served people in American housing. Peter Salons, of Hunter College in New York, emphasizes that "homeless people are merely the most visible portion of the unattached who need housing; there are many more." He continues that these people "do not all need apartments; they need rooms ."[70]

Twenty years of the SRO crisis and of determined study and activism have not produced the massive housing program that is needed, but they have set the stage for such a change. Perhaps the most necessary shift is a broader point of view about urban space, a move away from the monolithic one-best-way approach that gained currency in the late nineteenth century.

History, Urban Experts, and Pluralism

No single profession is responsible for all of the past misunderstandings and omissions of hotels within the range of American housing types. Nor does any single group have the power to instantly expand the notion of home, one of the most complicated and deeply rooted ideas in culture. Yet designers and planners, past and present, have operated at an important nexus in preserving the status quo as well as in fostering change. In part, this role falls to designers because they are trained to think of the future. Unfortunately, they are rarely educated to understand the present or past, particularly not the ordinary environments of the present and past. This has caused problems in the history of hotel housing. During the Progressive Era, social workers and social hygiene experts most successfully focused on what existed; the designers fo-

cused resolutely on what ought to be and often relished the utopian role they wanted to have, rather than the social servant role they told themselves they were performing. Grounded in the dominant class and its culture—whose values and hopes they usually shared—they wrote the official rules and fashioned leading examples of what was and what was not acceptable housing culture. Mary Burki, Peter Marcuse, Robert Goodman, and others have written about this cultural imperialism that has haunted the public housing movement from its inception. Until the 1970s (and in many cases, continuing into the present), planners and architects defined ideal residential environments of both the suburbs and downtown based largely on their own rarefied personal experience and professional design perspectives.[71] They ignored any conflicting evidence. In 1968, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown wrote that "learning from the existing landscape is a way of being revolutionary for an architect."[72] This is still true.