Chapter Eight—

From Scattered Opinion to Centralized Policy

Criticizing hotel life was one thing; effectively controlling it was another. By 1910, reformers had established the idea that hotel housing was a public nuisance. From 1900 through the 1940s, interlocking groups of reformers and landowners transformed objections about hotel life into practices to control living in hotels. For the goals of the culturally and socially reorganized new city to succeed, aberrant forms of housing had to be prevented and removed—slum and hotel alike. Yet gaining control was neither automatic nor preordained. Hotel housing was entrenched in some areas and in others, still expanding (fig. 8.1). A few handfuls of reformers had to do more than galvanize public opinion against the notion of living in hotels; they also had to establish whole new governmental organizations and procedures to give cities and states the necessary legal and bureaucratic power.

At first, California's housing officials developed innovative views of hotel living as a viable (if problematic) part of the state's housing stock. Yet after experimentation with policies different from those of the Midwest and East, California reformers adopted more negative hotel attitudes; as expert actions shifted from the state to the federal level, the power and the uniformity of antihotel policies increased as well. In the 1890s, Californians believed that incremental improvements—

Figure 8.1

Rooming house sign near the Iowa State Capitol, 1940. Legislators in Des Moines did not have to

walk far to see single room occupancy as part of the slum problem.

moral conversion of one person at a time, remodeling of one building at a time with codes and inspection—were enough to eventually achieve the desired uniformity. By the 1920s, land-use planning and zoning provided stronger responses to hotel life. In spite of these efforts, complete central control remained beyond official grasp. Finally, in the late 1930s, the planners' projects gathered momentum from the dangerously paired strategies of narrow ideals and deliberate ignorance, the policies that would prove nearly powerful enough to eliminate hotel life altogether.

Forging Frameworks for Housing Change

Early housing reform organizations in California had elements similar to their models and counterparts on the East Coast. Dedicated volunteer activists privately defined a problem, became the leading experts as they gathered the best (or only) information, galvanized the support of people with influence, and having talent and good timing, shifted quickly from doing small local projects to influencing major legislation. When a friendly administration established an official agency, the lead

Figure 8.2

Portrait of Simon Lubin in 1913.

Lubin had just begun his work

as president of the Commission

of Immigration and Housing.

private reformer became the public agency head.[1] Thus, in California as elsewhere, the circuits of information and the conduits of antihotel opinion were directed by a relatively small number of people.

In California, the housing reform process was exemplified by the work of a wealthy volunteer named Simon J. Lubin and his creation, the state Commission on Immigration and Housing (fig. 8.2). Lubin's commission, a classic Progressive Era enterprise, had an enormous influence on the state's housing, planning, and zoning. Lubin was born to a wealthy Sacramento and San Francisco family. He went to Harvard University, and in his last two years there (from 1900 to 1902) he devoted himself to immigration problems. This work provided Lubin's tie to Lawrence Veiller and the national network of reform centered in New York. In 1903–04, Lubin lived at Boston's South End House, a social settlement, where he met such important housing experts as Albert Wolfe, Robert Woods, and Eleanor Woods. After living for an additional two years in a settlement in the slums of New York's Lower East Side, Lubin returned to Sacramento and went to work as an officer of the family business, a large international retail and wholesale dry goods company. His chance for more social activism came in 1912 with the election of a reform governor, Hiram Johnson. Lubin talked Johnson into forming a temporary commission on immigration which Lubin chaired. The following year, the state legislature created the permanent Commission on Immigration and Housing (CIH) with Lubin

as chair and with a full-time staff of twenty headquartered in San Francisco.[2]

More than Lubin's lobbying motivated Johnson and the legislature to create the CIH. In 1912, California had no slums of the style found in New York, but Californians were convinced that employment stimulated by the new Panama Canal would bring tidal waves of southern European immigrants to the state's cities. Demonstrations by the IWW, marches by migrant workers, and riots and killings on one of the Central Valley's giant ranches had also focused attention on the problems of migrant workers and their dwellings.[3]

Lubin enthusiastically picked up where a small local reform group, the San Francisco Housing Association, had left off after three years of work (1911–1913).[4] He also actively strengthened California's ties to national reform. He carried on an active correspondence with his Boston contacts, with experts at Hull House in Chicago, and with New Yorkers whom he hoped to attract for the executive staff of the agency. As a matter of course, Lubin joined the National Housing Association, and Veiller personally provided books, reports, and advice.[5] Lubin chaired the CIH for ten years, gave thousands of dollars to cover staff travel and research expenses, and spent weeks personally training the eventual succession of executive staff. By personally serving as a connecting link, Lubin helped to make an efficient transfer of ideas from the East Coast to the West Coast; the CIH staff routinely cited Veiller, Woods, Breckinridge, and Abbott in their publications.[6]

Lubin and the CIH generally shared and reinforced the values of California's major downtown property owners. As an officer of a large company, Lubin was well connected to the business and real estate communities (fig. 8.3). He also knew labor issues firsthand, as the family business employed a small army of skilled clerks and unskilled warehouse workers. To Lubin, better housing meant a more reliable working force with fewer turnovers in staff.

In retrospect, large-scale land developers and investors clearly needed expertise like that of the CIH to organize city services and to guarantee investments, just as the reformers needed the influence of the large developers to build the new city. Regulating undesirable development was one method of improving the value of urban real estate generally. However, the regulation of downtown and edge-of-the-city development helped the biggest developers most and hurt the "curbs-

Figure 8.3

Side view of Weinstock Lubin's store in

San Francisco, ca. 1900. Simon Lubin's father

was a founding partner of a dry goods

enterprise whose retail store loomed over

Market Street a block from Union Square.

toners," people dealing only in a few lots at a time. This congruence of CIH reform and big business was an irony typical of the Progressive Era. On the one hand, housing reformers fought to regulate land-owners and unscrupulous builders and educated the public about the fraud of the landlord class. On the other hand, the reformers had to join with the largest developers and downtown interests to operate and to get legislation passed.[7]

As if to demonstrate the bureau's alliance with downtown business interests, between 1912 and the late 1920s, the CIH jumped whole-heartedly into the California campaign for city planning and zoning, although those issues did not directly impinge on housing and immigration. Glowing reports about city planning—reported as "really more important than the housing problem, or the sanitary problem, or the transportation problem" (since it dealt "with the interrelation of them all")—appeared frequently in CIH publications.[8] As an example of overlapping interests, in 1914, Lubin and the CIH supported Charles Cheney, a young San Francisco architect and planner, to travel throughout the Northeast and prepare an ambitious exhibit to convert state legislators to proplanning and prozoning opinions. Cheney's father was Berkeley's preeminent commercial realtor, head of the Chamber of Commerce, and a prominent member of the California

Real Estate Association (CREA). In 1915, the CIH, CREA, and other supporters of central planning won the political debate. The legislature gave California municipalities the right to appoint city planning commissions, develop long-term plans, and regulate the subdivision of land. The assumption—correct or not—was that compared to politicians, experts would be more objective and scientifically more value-free in shaping the city.[9] After 1940, city planners were to become prime actors in the fight against culturally aberrant hotel housing.

The most focused housing projects of the CIH were two habitation laws, one passed in 1917 and one passed in 1923.[10] With these uniform laws applied to all communities in the state and with the active assistance of the CIH, most large cities in California had at least nascent city planning and zoning by the early 1920s. Furthermore, the people involved had the service of a set of central bureaus for comparing work and disseminating information and influence. Also by the 1920s, adding to their old health departments, most large California cities had appointed the first trained housing inspectors for their building departments.

These reform actions boded ill for the commercial experiment of hotel living. Thirty years earlier, the New York police inspector, Thomas Byrnes, had said that cheap hotels were "not a case for a palliative; as Emerson would say, it is a 'case for a gun'—for the knife, the blister, the amputating instruments."[11] The work of people like Lubin, Cheney, and the CIH and the aid of their laws, competent staffs, and zealous building inspectors meant that California's antihotel reformers not only had the knife and the blister for slum clearance but also the amputating instruments to begin removing the institution of hotel residence.

Early Arenas of Hotel Control

As reformers organized to fight urban architectural problems, they did not move from one strategy to another in a simple chronological line or scale of intervention. Nor were all of the measures Progressive Era developments. Some of the strategies, particularly moral codes, had been tried in California well before 1912 and the founding of the CIH. The targets also shifted. The reformers aimed their building codes particularly at cheap lodging houses and the worst rooming houses—the

bottom two-thirds of the hotel market. Zoning promised to control the entire market but only in the new sections of the city.

Enforcement of Moral Codes

At the simplest level, reformers sought to control what they perceived as aberrant social lives by controlling the behavior itself. Beginning in the nineteenth century, various San Francisco reform committees fought for city controls against the sins of downtown life; they did this as a part of their mission hall programs, temperance promotion, and dance hall crusades. In 1903, the city's Board of Supervisors passed a set of mild restrictions against dancing, gambling, sexual solicitation, and cross-dressing. The city's gambling and whorehouse activities continued unabated.[12] In 1913, the state passed the Red Light Abatement Act, allowing authorities to close prostitution houses for up to a year. The Northern California Hotel Association joined the coalition that lobbied against the law, fearing that enforcement could too easily be brought against hotel owners. American entry into World War I stimulated a high wave of concern about vice districts. The ever-active Simon Lubin—with an eye to hotel connections with prostitution and as a member of a Sacramento welfare commission—railed against police corruption that kept "unregulated hotels and lodging houses spreading venereal diseases among the soldiers" at the local army camp.[13] Not all sexual alarms about hotels focused on prostitution or troop safety. Some social agencies recommended that hotel managers bar boys under the age of seventeen from cheap lodging houses, or at least prevent boys and men from rooming together, because of the dangers of homosexuality. For similar reasons, reformers elsewhere urged police to keep city boys from loitering or playing in streets and parks near the cheap lodging house districts.[14]

In 1919, federal Prohibition eliminated drinking in hotel bars and dining rooms and thereby slashed the most lucrative profits of hotel operation. The California Anti-Saloon League and the local WCTU, however, could do little to enforce Prohibition in San Francisco. As in the hotels of other cities, Prohibition merely moved drinking from the management-supervised areas of San Francisco hotels to private rooms, with dire consequences for furniture maintenance and cleaning bills.[15]

Parlor reform—the campaign to require sitting rooms in tenements and rooming houses and thereby to encourage quiet home life—was a milder moral reform that also affected hotels. In 1927, the Girls Hous-

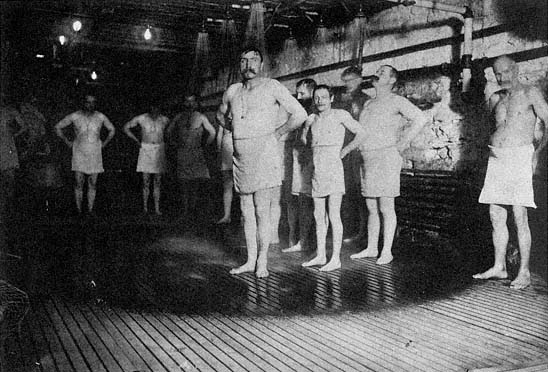

Figure 8.4

Creating social reform by changing individual behavior. Men taking a compulsory shower in a

New York City public lodging house, ca. 1900.

ing Council of San Francisco decried the long absence of rooming house parlors. Blocked from their goal of laws requiring sitting rooms, the matrons of San Francisco (like women's groups elsewhere) compiled a private registry of rooms. Volunteers inspected each address in the San Francisco registry and judged its respectability, cleanliness, and comfort. The resulting list was designed to prevent single girls from getting into morally dangerous situations when they followed up newspaper ads for a room. Some YMCAs offered similar services for men.[16] This regulation of behavior by private inspection was another means of changing or enforcing individual action.

For hoboes and other poorly dressed people, control of behavior was more direct and often rougher. When police caught drunks or panhandlers out of bounds in San Francisco, they were summarily sent back to the parts of the city "where they belonged" and roughed up if they did not go kindly. The showers required at least once a week in some municipal lodging houses were yet another means of inducing new behavior as well as hygiene (fig. 8.4).[17]

Control over hotel life simply by control of behavior proved ineffective. Prohibition's financial effects on hotels were unintended side effects and hurt the better hotels more than the cheap rooming houses. Laws regulating drinking, dancing, and other social life required constant enforcement that was impossible to provide. In contrast, regulating the environmental conditions of cheap hotels offered an approach that was literally more concrete and, to most observers, far more effective.

Building and Health Codes

Initially, housing activists were often convinced that building code enforcement was the answer to better housing for the poor. "The solution of the housing problem," Veiller wrote, "is to be found chiefly in legislation preventing the erection of objectionable buildings and securing the adequate maintenance of all buildings."[18] As part of the general implementation of codes, regulation writers attacked fundamental problems of hotel safety and sanitation: firetraps, dark rooms, inadequate plumbing, and insufficient ventilation (fig. 8.5). An entire system of codes had to be implemented. After initial passage of the ordinance came the training of staff to review plans, inspectors to check construction of new buildings, and often another set of inspectors to find later management violations.

San Francisco's earliest attempts to regulate hotels and lodging houses began in 1870 with an ordinance requiring sleeping rooms with at least 500 cubic feet of air space for each lodger; the state passed a similar ordinance in 1876. These laws were primarily aimed at the dwellings of single Chinese laborers. A Sacramento newspaper editor protested the discrimination, asking, "What better right has a Chinaman than a white man to be ventilated?"[19] However, enforcement was used not for environmental improvements but mostly for racial harassment. By the turn of the century, an occasional health inspector did invoke the 1876 law for the worst white lodging houses. San Francisco's other early hotel ordinances were concerned less with health and safety and more with licenses and fees, that is, until the 1906 earthquake and fire.[20] In the first year following the fire, the corrupt administration of boss Abe Ruef and Mayor Eugene Schmitz allowed almost any rebuilding scheme, which outraged reformers. In a political backlash of 1908 and 1909, activists rewrote the city plumbing and building

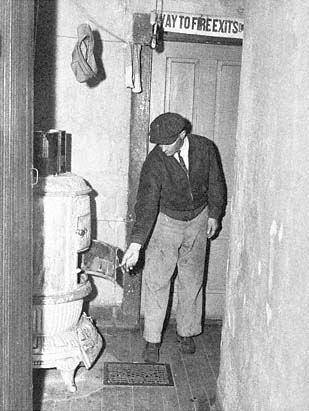

Figure 8.5

Heating stove in the hallway of a cheap hotel, Dubuque,

Iowa, 1940. Code enforcement worked to eliminate

hazards such as stoves which blocked access to fire exits.

laws. For the first time, health inspectors had the power to close non-conforming buildings. Also for the first time, San Francisco building owners experienced serious code enforcement; in 1909, the permit office rejected 75 percent of all the applications submitted. The single section of the new city building codes aimed specifically at hotels allowed cubicle-type rooms only in the most permanent and fireproof buildings; new, large, hastily constructed wooden lodging houses were outlawed.[21]

All subsequent hotel code restrictions came from the state. In 1909, California's legislature approved the first state housing law, a virtual carbon copy of the tenement code Veiller had written for New York City. California housing activists were not happy; they said legislators had been duped by the state's builders into allowing the densities of six-story Manhattan-style tenements when such buildings had not yet appeared in California cities.[22] The only mention of hotels in the 1909 state law was a significant "stables/lodging houses/rag storage" clause copied from Veiller:

No horse, cow, calf, swine, goat, rabbit, or sheep, chickens, or poultry shall be kept in a tenement house, or within 20 feet thereof on the same lot, and no tenement houses or lot or premises thereof, shall be used for a lodging house , or stable, or for the storage or handling of rags.[23]

Like Veiller, the California legislature had classified cheap hotels along with cattle and volatile rags as a prohibited nuisance use.

In 1913, prompted now by Lubin and his CIH experts in Governor Johnson's reform administration, state officials passed a short seven-page act specifically regulating hotels and lodging houses. The provisions of this act and other early actions show that the CIH, compared to its eastern counterparts, more actively included hotels in the public vision of housing. The CIH included officials from hotel organizations in their deliberations; they warned the city officials of Stockton, California, that they should supervise the construction of hotels as well as tenements or else slums would spring up. The first CIH housing survey included twenty-nine cheap lodging houses along with an area of immigrant cottage tenements.[24]

In 1917, the CIH pushed the legislature further. The state passed a trio of housing acts: a single dwellings act, a new tenement house act, and a comprehensive hotel and lodging house act that was very innovative. The new hotel act was thirty-nine pages—matching in detail the forty-one-page tenement act. The CIH properly crowed that its hotel law was "the most comprehensive in the U.S."[25] The Californians were breaking with standards automatically imported from elsewhere and were responding to local conditions with local ideas. This experiment in regional diversity would prove to be relatively short-lived.

Laws of other states had stronger details, but in its general conception, California's 1917 hotel act showed the framers' close familiarity with cheap hotel life. They allowed existing cubicle rooms to remain, and they included guidelines for open dormitory rooms; however, they outlawed new cubicle hotels.[26] Most important, the act set lasting bath-to-room ratios for the cheapest lodging houses: a separate water closet and shower on each floor for each sex, at the minimum ratio of 1 per 10 rooms or guests. Owners of existing hotels had to bring their toilet room ratios up to 1 to 12. These were strict requirements for the times. San Francisco's old requirements had been a ratio of 1 toilet room to 25 guests; New York required 1 water closet per 15 beds. The California hotel code matched the minimum window areas, room sizes,

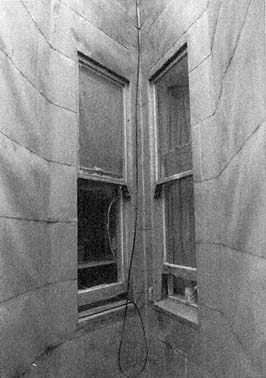

Figure 8.6

Window well in a San Francisco hotel built

to the city's 1909 codes. Later state housing

acts forbade narrow air wells like this one

at the National Hotel, a large rooming

house on Market Street.

Figure 8.7

An imposing inexpensive hotel on two lots

next to smaller downtown rooming houses.

The scale of San Francisco's 82-room

Hillsdale Hotel, built in 1912 on Sixth Street

in the South of Market, was the wave of

the future for this building type.

and floor area per occupant in concurrent tenement house standards (fig. 8.6). In the new tenement act, the CIH had also rewritten Veiller's "stables/lodging houses/rag storage" clause so that it no longer included lodging houses as a nuisance use.[27]

The new California housing codes also worked for greater separation of people within more specialized rooms. Hotels and apartments were to have separate toilets for employees and guests. The 1917 code also contained this language about the separation of cooking and sleeping:

Food shall not be cooked or prepared in any room except in a kitchen designed for that purpose. Floors of kitchens and rooms in which food is stored shall be made impervious to rats by a layer of concrete . . . or a layer of sheet tin or iron or similar material.[28]

Local housing inspectors later had inspection forms listing "cooking and sleeping in the same room" as a violation category along with infractions such as "undersize rooms," "overcrowding," and "insufficient toilets." Kitchen measures like these were aimed at illegally sub-

divided houses and other light housekeeping rooms whose owners avoided inspection by not declaring cooking uses. Unbending rules on separate kitchens would become a major hurdle for the maintenance of hotel life after World War II.[29]

State housing inspectors kept up the code pressure on cheap hotels. Of the total inspections made in California cities in 1918, miscellaneous dwellings (largely shacks) required 26,000 inspections. More hotels were inspected (6,900) than tenements and apartments (5,900). By the 1920s, local San Francisco authorities had established a separate department of hotel and apartment inspection.[30]

Building codes had more specific effects than moral codes. For existing California hotels, code enforcement often raised rents but also spurred significant improvements for residents. As full-scale building inspection in San Francisco began in the 1920s, inspectors could—and did—push landlords to provide more livable amounts of ventilation and plumbing. Surviving records suggest that by 1930 even landlords like Edward Rolkin had brought their cheapest lodging houses close to the toilet and sink codes, even if the hotels did not benefit from regular cleaning.[31] For the rooming house rank, codes tacitly encouraged San Francisco speculators to provide larger, more prominent buildings (fig. 8.7). In 1910, small rooming houses with 15 to 40 rooms in a three-story walk-up building outnumbered larger rooming house buildings three to one. By 1930, three-fourths of the rooming house rooms in San Francisco were in large five- and six-story buildings with 70 to 160 rooms and elevator service. Along with efforts to reduce management costs and use more efficient mechanical systems, codes played an important part in this jump in scale (fig. 8.8). The larger light wells and more complicated plumbing also made the new, more specialized rooming houses less likely to be converted to commercial uses without substantial waste and unrentable space.

The more expensive hotels in San Francisco already had standards far above the code minimums. Thus, owners of the better hotels had little to fear from city housing inspectors, except for permanent guests who kept trying to cook in their rooms. One change seemingly a result of the 1917 codes was the end of California experiments with buildings that mixed rooming house units in apartment buildings. One such structure had thirty-six rooms with baths down the hall (all in the back of the building) and forty-five full-fledged apartments.[32]

Figure 8.8

Typical sizes of rooming houses before and after effective building code

enforcement in San Francisco. Right , a 26-room structure built in 1910 with small air

shafts; left , a 157-room structure built in 1915 with the required larger air shafts.

Except in rare condemnation cases, building and sanitation codes controlled hotels but did not eliminate them from the housing stock. Research on Chicago has shown that codes enforced there in the 1920s made new cheap lodging houses unprofitable—thus retarding new construction of such hotels.[33] In San Francisco, the hotel supply was already plentiful and probably overbuilt after World War I. These uneven results of code regulation discouraged even Veiller. He wanted more of the city to be rebuilt, not just brought up to code minimums. More than once he expressed a wistful desire that New York "might be purified by fire, and that whole sections might be thus destroyed."[34]

Veiller's influence, along with his National Housing Association's focus on codes, waned in the 1920s. Codes were seen less as primary tools of social and cultural control and more as assurance for mortgage lenders and insurance agents. In other city departments, however, planners had been hammering out a way not simply to control the present but to control the future of the whole city.

Zoning to Control Future Growth

Citizens who shared the vision of the new city were uniformly concerned about mixed land use and high residential density. These were problems beyond the scope of building codes and good intentions (figs. 8.9, 8.10). Over the heads of all urban land investors hung the vultures of uncertainty and unpredictability, or as one developer put it, the problem of "premature and avoidable de-

Figure 8.9

Street view of middle-income two-family and four-family houses on

Avon Street in Oakland, California, constructed between 1910 and 1925.

The light-colored Avon Hotel, at rear , appears to be another house.

Figure 8.10

The Avon Hotel as it appears in the middle of the residential block.

Most zoning codes outlawed reproducing experiments like these.

preciation."[35] Moreover, one owner's adherence to codes had no automatic effect on buildings next door. If neighboring properties were sharply incompatible, spewing out noxious fumes, or crowded with the urban poor, then the value and potential use of even the best new building was sharply diminished.

The real estate industry in San Francisco, like its counterparts in other cities, first encouraged the use of restrictive covenants at the edge of the city to exclude nuisance uses, to prohibit subdivision of houses, and to disallow selling or renting to blacks, Asians, or Jews. The largest

use of restrictive covenants in San Francisco came in the new elite sub-divisions opened on the city's western side. But developers still worried that construction on the adjacent tracts could spoil their property values.

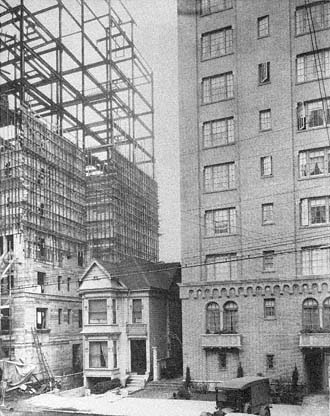

Closer to downtown, in the Western Addition, real estate promoters had the opposite problem. They wanted to ensure that the district would reach a higher density and do so with uniform heights and uses. Some Western Addition owners were building ten-story apartment towers on prime lots, but their structures stood next to old two-story Victorian houses or light housekeeping rooms (fig. 8.11).[36] Expert reformers taught that widespread land-use zoning, not covenants, would be the logical solution to keep such "old conditions in the larger cities" from "reproducing themselves" in outlying districts. Paul Scharrenberg, one of the five CIH commissioners, promoted zoning in San Francisco as a means to guide "right city growth." Veiller, too, called for zoning specifically "to keep apartment houses and hotels out of the private-residence districts."[37]

Whether one was using restrictive covenants or zoning, controlling land-use mixture and density carried negative implications for hotels. Banning retail activity from a housing neighborhood attacked one of the vital notions of hotel life—the home that was scattered up and down the street, with one's bedroom in one structure, the dining room at the local café, and so forth. Banning multiunit buildings next to lower-density structures struck at the notion of ad hoc rooming houses. As local and national zoning precedents were set, these implications for California hotels came more sharply into view.

San Francisco's zoning act, passed in 1921 and slightly modified in 1927, had typical antihotel provisions. For most unbuilt areas within the city limits, the act established "first residential districts" featuring the new city ideals of separate, single-family houses. Only religious, professional, and bucolic uses could be mixed with the residences; commercial mixtures were banned (fig. 8.12). Musicians, doctors, and dentists could work out of their home but not plumbers or auto mechanics. Nurseries, farms, truck gardens, and greenhouses were allowed but not corner grocery stores or bars. Zoning thus made uniform land use and desired densities as enforceable as the requirements for interior plumbing.

Figure 8.11

Nonuniform development in the northern reaches of

San Francisco's Western Addition, 1927. Investors saw a

surviving Victorian-era house like this, probably a rooming

house, as a threat to the property value of the tall buildings.

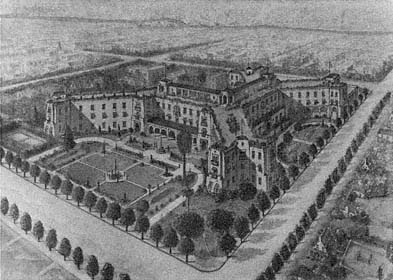

Figure 8.12

The "intrusion" of an auto dealership into a residence district. Illustration of negative land-use

mixture from a 1920 article promoting zoning.

Hotels were allowed in three of the other zoning categories. Mapped as "second residential areas" were the city additions built from 1880 to 1921. In such areas, the zoning ordinance allowed apartments, hotels, and six specified neighborhood institutions (libraries, for instance); however, new stores would not be allowed. Existing streetcar corridors with their lines of shops were in the commercial category, and hotels were allowed there. After a series of political appeals, hotels were also allowed in heavy industrial districts.[38]

With so many areas of San Francisco open to hotels in 1921, the effects of zoning may not seem significant. Indeed, the antihotel ideas within zoning ordinances did not initially affect hotel life significantly; yet they reshaped a debate that had dramatic effects several decades later. On the one hand, zoning gave city officials centralized power over the form of future locations for hotel life. On the other hand, zoning drew a very effective cordon sanitaire around the old city as it had been built by about World War I, to keep old city ideas from contaminating the new city. In these respects, zoning came to be powerful in several ways.

First, the inflexible administration of zoning cut off suburban hotel experiments such as the hotels built over corner groceries or corner bars in new additions to the city. Zoning laws and opinions could have been written to keep only the worst aspects of mixed use and mixed building types out of urban expansion. Bulk, occupancy, or lot-coverage guidelines written as performance criteria rather than as absolute proscriptions might have allowed hotel managers to continue experimenting with expensive one- or two-story hotels whose form, image, and clientele would have blended even with new automobile suburbs. Ample precedents for such congenial mixtures could be found in country clubs that coexisted with the most exclusive suburbs.[39] Had suburban developers actively fought for such variety in early applications of zoning, they probably would have won over the experts' objections.

Second, zoning retarded the establishment of new rooming houses even in those extensive older areas of San Francisco designated as second residential districts. New hotels were entirely legal in these areas, but zoning forbade other new commercial uses. Hence, the critically important tenant services and cash flow from first-floor business were

unhinged from the rooming house business above, sharply reducing profits.[40]

Third, the long strips of commercially zoned blocks on either side of streetcar and new automobile through-routes proved to be inhospitable to new hotel life. The older streetcar strips and nodes already had a mixture of hotels and rooming houses. At the newer edges of the city, hotel residents found incomplete commercial services, a narrow range of prices, or too little variety: eating at the same inexpensive restaurant every day did not support convivial hotel life. Farther out, in nascent automobile strips, pedestrian life was unpleasant.

A fourth effect was a consequence of eliminating rooming houses in suburbs. Rooming houses had allowed women to make a living within one of their traditional roles, keeping house.[41] Zoning in effect eliminated expansion of these women's businesses.

Fifth, a succession of court decisions supported the elite and professional opinion that hotels should be excluded not only from the growing edges of the city but also from the entire city. It did not matter that hotels were popular or necessary or chosen as homes by a fraction of the downtown public.

The early court cases testing zoning show the degree to which hotels and rooming houses were on the minds of urban land-use experts. Initial state supreme court reviews disagreed about such basics as any land-use exclusions and zoning's uses of the police power; thus, excluding hotels, flats, and apartments from areas of single-family houses was logically more difficult for the courts. Miller v. Los Angeles , an influential case heard in 1925 before the California Supreme Court, summarized several earlier antihotel court opinions. The judges upheld the exclusion of a four-flat building from an area of single-family houses, and their opinion ranged widely to discuss apartments and hotels as well as flats.[42] They admitted that "undoubtedly, many families do maintain ideal home life in apartments, flats, and hotels" and that "in many single family dwellings there is much of dissention and discord." Nonetheless, the court also assumed that life in apartments and hotels was never chosen:

Few persons, if given their choice, would, we think, deliberately prefer to establish their homes and rear their children in an apartment house neighborhood

rather than in a single home neighborhood. . . . It is needless to further analyze and enumerate all of the factors which make a single family home more desirable for the promotion and perpetuation of family life than an apartment, hotel, or flat.[43]

This ruling influenced other courts. The Minnesota Supreme Court in 1925 rationalized exclusion of multiple-family structures as a reasonable reaction to urban population pressures.[44] A judge in Cleveland, Ohio, bluntly repeated the opinion that apartment buildings not only spread infectious diseases but also promoted immorality.[45] Many of the court opinions invoked expert academic scholarship—like that of the Chicago school of sociology—to reject apartments and hotels as valid housing. A law review article said "sound sociological arguments" led to the belief that open-lot houses were better than flats.[46] In fairly subtle ways, the decades of objections to hotel life by national figures such as Veiller, Woods, Abbott, and Park and California figures like Lubin and Porter had an important effect.

The gathering of antihotel opinion was particularly clear in 1926, when the Supreme Court of the United States handed down its decision on Euclid v. Ambler , the landmark zoning case concerning a Cleveland, Ohio, suburb and a small local realty company.[47] Writing for the court, the archconservative justice, George Sutherland, not only upheld the private house ideal but also helped to relegate all hotels and apartments into the category of hazards for the new city. Sutherland found no problem supporting the exclusion of industrial activity (as a nuisance) from residential areas; more difficult, he said, would be the "creation and maintenance of residential districts, from which business and trade of every sort, including hotels and apartment houses, are excluded." For this exclusion, the court could not rely solely on the concept of nuisance. Instead, said Sutherland, the court was convinced by "much attention at the hands of commissions and experts" that apartments and hotels, like steel mills, were a hazard to public health and safety when they were placed next to single-family houses (fig. 8.13). Within one year after Euclid v. Ambler , forty-five states had enacted enabling legislation for local zoning. Municipal and state courts were henceforth freed from the narrow confines of the common law of nuisance and police power that had constrained the limits of earlier building and health codes.

Figure 8.13

An apartment and tourist hotel in a residence district of the San Francisco

Bay Area suburb of Alameda. Opinions on the mixture of houses

and hotels varied widely: the city's Chamber of Commerce began this

hotel in 1926, the same year as the Euclid v. Ambler ruling. In the 1990s,

small bungalows and Victorian houses still abutted the hotel on two sides.

In 1932, President Herbert Hoover summed up the argument: "Zoning and city planning save waste, reduce ultimate costs, and add attractiveness and other social values to stable investment values for home owners."[48] For Hoover, investment stability was the ultimate social aim, just as it was for the majority of those who gained from the notion of an immutable new city. When reformers elevated the ideal of the privately owned American home as the single goal of national policy, the idea grew dramatically in power. This single-minded focus on the single-house concept would become in itself another strategy for eliminating hotels and apartments.

Doctrinaire Idealism and Deliberate Ignorance

Codes and zoning prompted immediate, specific actions. Their effects could be measured and plotted. Two later and more veiled strategies—setting narrow housing ideals and consciously creating holes in official intelligence—were seemingly less direct. Nonetheless, they became much more powerful and pervasive actions in the long run, in part because they were prescribed from a national level.

Working for a Single Ideal

When urban reformers set their architectural agenda for the new city, they realized they had to do more than

control bad housing. They also had to promote correct housing, their favorite being the uniform and protected single-use residential district of private houses with open lots. An underside of the process of defining housing ideals was the necessity of drawing the line where housing stopped and mere shelter began—or as later urban renewal officers put it, the line between standard housing and substandard housing. The definition of "standard" would come to insist on private kitchens and private baths, precisely the two items that most hotels did not provide.

At Hoover's presidential conference on housing in 1932, the Committee on Housing and the Community enunciated again the housing specialists' long-standing model:

The ideal conditions for any family would be a single detached house surrounded by a plot of ground, with adequate lawns and facilities for a small flower and vegetable garden and play space.[49]

The 1932 committee closely matched the phrase "any family" with the single detached house: like the California Supreme Court, they could not conceive of a minority opinion among people who preferred apartment or hotel life. Moreover, electric trolleys, automobiles, and longerterm mortgages had made the open-lot house more possible.

For several generations, preeminent concern for the welfare of children had figured heavily in the evolution of the reformers' choice. When Veiller spoke of "labor" and "workingmen" he meant laboring men with families, and inevitably he followed with a reference to "making family life possible" or concern for "wives and families." Veiller insisted that the "normal method of housing in America" should be small houses on their own "small bit of land," offering "a secure sense of individuality and opportunity for real domestic life" and the suburban advantages of healthful play for children.[50] The CIH proudly published its model rural work camps for single workers but never considered model dwellings for single workers in the city. In 1915, the commission proclaimed that the comprehensive city plan "should provide for detached one-family houses, with lawn and room for rear garden. This is the ideal arrangement."[51] Soon the ideal form of housing became the only acceptable form.

Whether or not they housed children, apartments and hotels both fared poorly in expressions of housing ideals. E. R. L. Gould, the foun-

der of New York's City and Suburban Homes Company, reminded his colleagues that for the better-paid worker, model apartments would be (at best) an intermediate stage between the "promiscuous and common life" of existing city forms and "the dignified, well-ordered life of the detached house." Edith Elmer Wood wrote that "the only excuse for apartments is for celibates, childless couples, and elderly people."[52] In practical application, however, the apartment had to be accepted in local and national construction programs. Physical separation of each family unit remained of paramount importance—the minimum elements of division being the private kitchen and private bath for each unit.[53]

For some time a minority of reformers doubted the necessity of private kitchens for every family. Social workers at a national conference in 1912 called for an indoor bathroom for each low-income family but not private cooking. New York City's housing reformers, however, had insisted on private kitchens in definitions of tenements and apartments written in 1887 and 1910. In these influential codes, an apartment was a unit in a building for three or more families "living independently of one another and doing their own cooking."[54] By the 1920s, the kitchen gained universal consideration as an essential element in the definition of a dwelling unit. By 1950, the U.S. Census defined an apartment's "separateness and self-containment" on the presence of separate cooking equipment for each household.[55]

Limiting the housing ideal required that hotels and lodging houses be legally defined as inferior to apartment buildings. That process had begun with the writing of state building codes but was most effectively accomplished with the establishment of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). Under Title I of the National Housing Act of 1936, Congress stated that property improvement loans could be secured for any residence or commercial building, specifically including hotels and clubs. Yet the act also required that the FHA eliminate risks as much as possible for the investors of the funds.[56] That was the sticking point. The 1936 FHA Property Standards set the most influential definition of proper housing to that date, with strong exclusionary language about hotels. Although the guidelines defined a dwelling as "any structure used principally for residential purposes," they carefully stated that "commercial rooming houses and tourist homes, sanitariums, tourist cabins, clubs, or fraternities would not be considered dwellings

within the meaning of the National Housing Act" that had created the FHA. A proper living unit required a private kitchen and a private bath.[57] Although this proscription was largely meant to exclude ad hoc rooming houses from federal aid, it was to prove handy in discriminating against single-room housing with or without federal aid.

Simultaneously, the minimum Property Standards stated that "the [insured] property should be located in a neighborhood homogeneous in character," a neighborhood sure to avoid "inharmonious land uses." In the FHA's codification of the real estate industry's values, residential hotels and their mixed-use neighborhoods were categorically "undesirable community conditions"; they "decreased mortgage security."[58] National underwriting manuals of the FHA appraisers gave low ratings to any residential property in a crowded neighborhood, one with racial mixtures, or one with a mixture of "adverse influences" defined as stores, offices, or rental units. These redlining policies extended the biases of zoning to the realms of investment and repair funding. Simultaneously, controls over rental properties were more complicated than for owner-occupied housing; most loans for repair of existing structures were small and short term. With the FHA it was easier to purchase a new building. Hence, FHA insurance helped new houses and apartments at the urban edge far more than any housing or infill in the center city.[59] In the 1950s, many cities further narrowed the definition of a standard dwelling by rewriting their older zoning ordinances to exclude rooming houses from the definition of multiple-family dwellings.[60]

With the national FHA property standards, underwriting manuals, and the increased importance of the income tax preference for single-family house ownership, real estate lobbyists and housing activists had successfully established suburban single-family houses and occasional apartments as the sole ideals for new American house types (fig. 8.14).[61] Meanwhile, during the depression and World War II, other government offices began a hotel control process far less observable but much more insidious.

Deliberate Ignorance as a Professional Strategy

The early activities of the San Francisco Housing Association and the CIH demonstrated that learning about a problem often brought administrative power to

Figure 8.14

The New Deal housing reformer's minimum. The model town of Greendale, Wisconsin, photographed

in 1939, just after its construction.

new urban professionals. Later experts proved that ignorance could also have power: if urban experts deliberately created ignorance about a problem, that issue was assured relative oblivion—assuming there was no political activism on the part of the public. Perhaps it was his observance of similar effects of nineteenth-century government administration that led Goethe to write, "There is nothing more frightening than active ignorance."[62]

One sociologist's research in 1948 uncovered the process of deliberate ignorance to be notably at work in regard to single people and hotel life. Arnold Rose exhaustively surveyed the literature about the living arrangements of single people, especially in the settings of rooming houses and cheap lodging houses. From a low point before 1890, interest gathered until 1915 and relapsed into disinterest after 1920.[63] San Francisco's Progressive Era interest closely matched Rose's model. The State Tuberculosis Commission had inspected the city's hotels carefully; the earliest CIH surveys in the city included problem hotels and led to the state's hotel acts of 1913 and 1917. The drop in California interest after 1920 matched the national trend.[64]

Idealistic studies of families and children and the simultaneous omission of single adults also helped to allow the growing professional disinterest in nonfamily households. As usual, Veiller serves as both exemplar and partial cause. At no time was he notably interested in single people or their housing. On a visit to San Francisco in 1902, he reported that the poorest living quarters were the "homes of the longshoremen, situated near the docks, . . . containing two families each." To be near the docks and those duplexes, Veiller had to walk past blocks full of rooming houses and hotels for single longshoremen, but he apparently did not notice them. He concluded, in fact, that San Francisco had no tenement problem at all.[65] In 1903, Veiller and Deforest's massive two-volume collection of articles about America's housing problems contained only a few passing mentions of hotels. In his 1910 book, Housing Reform , Veiller mentions hotels only once, in the context of high-class hotels. His chapters on housing investigations were written only for apartments and single houses.[66] In short, as Veiller and others framed the urban housing concerns of the United States, they purposely left hotels out of view.

Activists elsewhere reproduced the blind spots in the New York models. When San Francisco finally appointed two housing inspectors for the Board of Health, the commissioners dubbed them "tenement house inspectors," thereby setting a narrow focus for them. Similarly, reports by the San Francisco Housing Association dodged the subject of hotels. When they investigated housing problems in Telegraph Hill and North Beach, San Francisco's reformers incredibly made no mention whatsoever of workers' rooming houses or hotels, which dominated the Broadway border of both districts. The later work of the CIH was similarly silent in this regard.

Even during the positive wave of interest that crested in 1915, for every large book on family housing, usually only a slim article appeared about nonfamily people. By the 1920s, that token measure dwindled as well.[67] Consider how Edith Abbott discussed 60,000 men of downtown Chicago in her exhaustive summary of Chicago housing surveys undertaken between 1910 and 1936:

There are, of course, the large numbers of those who live in cheap hotels, boarding houses, and "flops"—the casuals who come and go in the "flophouses" near the loop. . . . No attempt will be made at this point to discuss the

hotels or shelters for single men since our interest here lies largely in the housing of families and in the tenements where families live.[68]

Abbott had a purely negative impression of hotel life derived from skewed samples. For her chapter on Chicago rooming houses, she relied on a 1929 thesis about a sixty-unit residential hotel; the thesis was based only on the five to ten families from the building (over five years' time) who had come to the United Charities offices for assistance. The thesis was based on the worst possible cases.[69]

Even that bastion of social statistics, the U.S. Census, largely ignored hotels—both as an industry and as homes. Although hotels ranked fourth or fifth in income and number of workers among American businesses in 1905, the editor of a hotel journal expressed his general frustration:

We have no figures, no statistics, no official rating . . . which we might compare with other industries. Our government which counts every mule, every bushel of wheat, which has figures on every possible production, has nothing to relate regarding legitimate hotel keeping.[70]

The editor was complaining that the census office reported only the number of hotel keepers, not distinguishing size or type of hotel. Census takers, of course, did enumerate individual hotel residents as part of the U.S. population. But the census staff has never aggregated those statistics to show accurately how many people have lived in hotels. The figures typically mix residents of hotels and rooming houses into those in other "dwelling units," or with military personnel, indigent residents of institutions, or residents of convents, monasteries, dormitories, or sorority houses.[71] These figures, at best, can supply only rough estimates. In 1930, the U.S. Census Bureau did publish a special report on the hotel industry, but it did not discuss permanent residents.[72]

Hotels continued to be out of focus for housing activists and city planners in the 1930s. In the seven report volumes of Hoover's national conference on housing, neither single-room housing nor the housing of single people was mentioned. The hundreds of excellent New Deal studies, reports, outlines, discussions, and conferences about housing problems included only very negative information about single-room housing, mostly on so-called homeless men, their urban flophouses and

shantytowns, and rural CCC and FSA labor camps.[73] Academic coverage of hotel housing continued to be virtually nil in the 1930s.[74]

As the depression wore on and instructions came more efficiently from Washington, D.C., instead of from local officials, New Deal reports—especially real estate reports—became increasingly conservative about including hotel information. The remarkable series of real property surveys is the most salient example. The first comprehensive real estate survey supported by federal funds was made in 1933 – 34 in Cleveland; most major cities followed suit in succeeding years. A revived San Francisco Housing Association had surveyed the Western Addition in 1933; other partial surveys were done of San Francisco in 1934 and 1936 to identify sites for clearance and renewal. These reports were done under municipal rather than federal guidelines, and all of the reports prominently featured hotels as part of the city's housing stock.[75] These early works were overshadowed by the much more ambitious citywide 1939 Real Property Survey of San Francisco.

San Francisco's 1939 Real Property Survey and its subsequent influence provide a stunning case of how deliberate ignorance can be created and perpetuated. For the survey, a small army of field enumerators collected room-by-room data about hotels as well as door-by-door counts of apartments, flats, and houses. However, following federal guidelines, the office staff then systematically excised hotels from the survey's compilations. In their summary volume, the staff devoted only 7 out of 253 pages of discussion and tables to San Francisco's residential hotels.[76] The meticulously detailed survey had found that one-third of both substandard dwelling units and ill-housed people of San Francisco were in hotels, but the staff hid this fact in procedural tables buried in the Appendix of the report volumes. The survey directors ignored the state's long-standing legal definition of hotels, split hotel housing into several different and conflicting categories, admitted that their survey of the 34,000 "primarily one-room dwelling units" in hotels was "an incomplete coverage for this type of permanent residence," and mildly suggested further study.[77] The 1940 U.S. Census of Housing (the first national census of housing) repeated the problems and biases of the real property surveys. The census collected information about hotels but annihilated that information in its reporting techniques.[78]

In 1941, the San Francisco Housing Authority reviewed the Real Property Survey and did ferret out comments about the city's nearly

Figure 8.15

Statistically invisible hotel. Using 1930s guidelines for real property surveys, the long and narrow

Hotel Frederick in Kansas City contained no housing units. Note "weekly rates" promoted on the sign.

five hundred hotels. The housing staff assumed the hotels had only recently been "converted from commercial to residential uses," erroneously supposing that all had been transient accommodations before the depression. Sounding a great deal like Edith Abbott, the San Francisco planners wrote that "due to the fundamental differences between these two types of dwelling units [hotels versus houses and apartments], the primary analysis and report on housing in San Francisco will exclude the dwelling units in converted hotel structures" (fig. 8.15).[79]

The basic data of the 1945 Master Plan for San Francisco—including its recommendations on land clearance—came directly from the 1939 Real Property Survey . The San Francisco Planning Commission incorrectly described the building types in the city's worst redevelopment areas as "generally three or four story flats or, as in Chinatown, tenement-type apartments."[80] The units in Chinatown were largely SRO hotels. In the South of Market, hotels were also a major share of the building fabric. Similar gaps of logic and description continued to appear in subsequent reports. The vacuum of information was such that in 1966, when William Wheaton and other housing experts compiled an authoritative 470-page series of readings on urban housing,

the only words on residential hotels or housing for single, transient, or unattached people were in a five-page reprint of a twenty-year-old article by Arnold Rose.[81] Until the 1970s, the well-meaning planners of San Francisco, like their contemporaries in other cities, continued their policy of carefully not studying hotels.

The omission in San Francisco's urban surveys of single-room housing units and the people who lived in them (rich or poor) seems incredible in the light of their downtown prevalence. Planners and officials in hundreds of other cities repeated the omission. This was neither oversight nor negligence but active repudiation. As Rose had warned in 1948, it was as if the people in hotel settings "were thought to be nonexistent, or at least entirely impoverished so that they could not expect anything by way of adequate housing."[82] He warned that this housing and its population presented an important problem, but his call to action fell on deaf ears. Rose became the Cassandra of today's single room occupancy crisis.

Because of the definitions of a proper American home, apartment units and their renters fared better. From the turn of the century, apartments were carefully watched and carefully counted as important resources. Writers and citizens heralded the building of apartment units as important housing additions to the city. The same was not true for most single-room options. Cheap apartments became a public concern and a public necessity; cheap hotels, if they were noticed at all, remained a public nuisance.

Buildings as Targets and Surrogates

To a downtown observer in 1945, the collective effects of all the attempts at hotel housing control—moral reforms, building codes, promotion of housing ideals, zoning, and deliberate ignorance—might have seemed ineffectual. Virtually all of the old rooming houses and cheap hotels were still standing. Where they had been torn down, it seemed that independent builders (such as the South of Market's Edward Rolkin) had simply replaced the old structures with larger and more threatening structures for the same resident groups.

Although the reformers seemed unsuccessful at first, their battles highlighted the active roles these ordinary buildings played in skirmishes over the cultural engineering of the city. Buildings were more

than passive strongholds of an old urban order and more than sullen threats to a new order. New buildings were also active tools for creating the king of urban culture that officials desired. Buildings, old and new, were also surrogate targets, substitutes for more radical or thorough solutions to human problems that were beyond the activists' power. Albert Wolfe, for instance, wrote in 1906 that the only real cure for the Boston rooming house problem would be job security and fair wages for the "mercantile employee as well as the skilled mechanic, the female stenographer as well as the man beside her." In private correspondence among themselves, the members of California's Commission on Immigration and Housing admitted that the most efficacious approach to slum conditions would be a land tax; simultaneously, they admitted that this solution was far too radical to overcome the opposition of private real estate interests.[83] Because reformers could not feasibly put such far-ranging issues on the agenda, they settled on buildings and land uses as surrogate targets.

At each higher level of government, the cultural control of housing became increasingly abstract and isolated. This abstraction was an inherent weakness built into the urban housing agenda after 1900. As reformers, lobbyists, and their bureaucratic machinery catapulted ideas from city to state and finally to the federal level, antihotel policies not only gained power but lost knowledge of local cultural diversities. As the San Francisco and California cases show, the ever more consolidated building codes and zoning definitions (ending with the FHA guidelines) had thwarted creative variations in local housing survey practice and sensitivity to local needs. In the decades after World War II, more centralized, more professionalized, and increasingly isolated housing staffs gained greater power for using buildings as tools of reform and as surrogates for greater action. The consequences of two generations of biased regulatory reforms, doctrinaire idealism, and deliberate ignorance would become massively apparent to the people managing and living in hotels after 1945.