Insufficient Materialism

By 1900, most Americans had settled into the belief that form of tenure—owning versus renting—could be used reliably to discern someone's social position in much the same way that race, income, occupation, and education were used. In interviews, poor house owners in Chicago said that owning a home made them "real

Americans" and gave them a means of achieving personal control over their world.[65] Since so many Americans anchored their personal and civic identities to their homes, reformers saw those who did not (or could not) as insufficient, deviant, or unhealthy. In short, renters were second-class, or perhaps third-class, citizens. Early observers warned that the rental aspect of hotel life's "dissipation" would engender "a distaste for steady and persevering application to anything."[66] Housing policymakers (property owners themselves) firmly agreed that both apartments and hotels would breed bad citizenship. In 1910, Veiller said this about apartment renters:

It is useless to expect a conservative point of view in the workingman, if his home is but three or four rooms in some huge building in which dwell from 20 to 30 other families, and this home is his only from month to month. . . . Democracy was not predicated upon a country made up of tenement dwellers, nor can it so survive.[67]

California housing activists concurred that the home, not rental property of any kind, was "the bulwark of good citizenship." Other California critics complained that if migrant workers saved money, it was only to send the money back home rather than invest it in the local economy. The migrants therefore had little desire to improve their living quarters.[68]

In an otherwise path-breaking book on urban housing, the influential planner Henry Wright flatly explained multiple-family homes as a result of irresponsibility:

[The inception of the apartment house] was brought about by the vaguely defined need of families whose habits were of a semi-transient nature, or those who did not care to assume the responsibilities of the independent house, and yet neither desired nor could afford the luxury of hotel life.[69]

Wright was one of many housing activists to carry Veiller's ideas into decades of later practice.[70]

For the business elites who directed Progressive Era housing reform, the bonds of rootedness and civic responsibility were woven out of mortgage payment receipts: personal financial interest in city real estate. Home ownership guaranteed accumulation of goods through thrift and self-denial. For some analysts, renters also undermined the

Figure 7.13

A building considered

dangerous to civic virtue.

A typical small apartment

hotel in New York City, 1903.

stability of centralized bank and mortgage control because they paid scattered individual landlords.[71]

Within the realm of renters, a distinction between hotel dwellers and apartment dwellers arose over the amount of personal possessions needed for a proper American home. Unlike apartment dwellers, hotel residents rented both their space and their furniture (fig. 7.13). To social observers and public policymakers, this unrootedness crossed the last boundaries of civic propriety. Official rhetoric required citizens to own furniture and dishes as the minimum evidence of stability and civic worth. For Wolfe, household goods and furniture were "those last anchors of men and women to a sense of ownership and permanent interest in a fixed abode."[72] Furniture was an important minimum for Edith Abbott, too. The great evil of the rooming house, she asserted, was neither landlord profit (as some reformers said of tenements) nor sanitary danger. Instead, it was "the degradation that comes from a family living in one room with broken, dilapidated furniture, without responsibility or a sense of ownership, . . . [with] nothing of their own."[73]

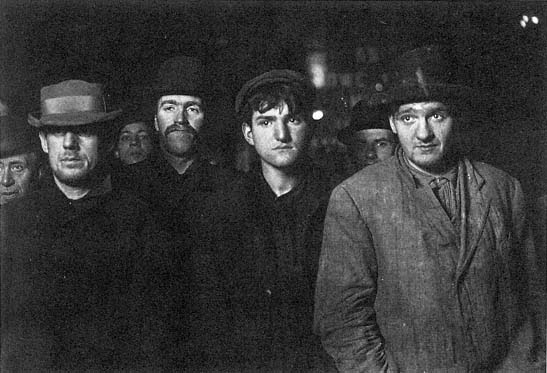

Figure 7.14

Citizenship not encouraged here. Part of a winter bread line at the Bowery Mission in New York City,

photographed by Lewis Hine in 1906.

For hotel and rooming house residents, the American dream of owning one's own house, yard, and furnishings often did not match the necessity of mobile careers and occupations. That mobility itself constituted another realm in the cultural threats of downtown living.