Demands for Separation and Low Density

For centuries, wealthy burghers in Europe lived only a floor or two away from their place of work and from their poorest employees, apparently with no significant contagion of poverty. By 1900, in America, such density, mixture, and adjacency were becoming highly suspect in the view of reformers. Critics chided comfortable hotel families who lived in suites of rooms for having a lack of privacy. Residents in cheaper hotel types were criticized for living with too little space per person and for mixing disparate activities in the same room.[35] Reformers blamed some rooming house crowding and mixture on un-American housing standards brought by immigrants from southern Europe, where large families often lived in one or two rooms. Social workers also deplored as "a demoralizing lack of privacy" the European habit of having the same bedroom occupied by grown brothers and sisters. Hull House social workers called a married couple and a child living in one or two rooms an "irregular method of living." What was combined in one room, they said, should have been separated and sorted out in "parlor, bedroom, clothes closet, dining room, kitchen, pantry, and even coal shed." Building inspectors

Figure 7.7

Pathological proximity. A rag picker and a middle-class

woman, at such close quarters, emphasized the

social schisms of urban life in 1875.

ruled that cooking in bedrooms caused vermin problems, dirtied bedding, and problems of inadequate ventilation of cooking odors.[36]

The fear of mixture and the desire for separation also manifested themselves in critiques of the "lodger evil"—the practice of families taking in unrelated men or women as renters. Lodgers often shared family bedrooms. Also seen as unwanted mixture were the "invasions" of housing districts by corner grocery stores, multiple dwellings, small factories, and repair shops. In reformers' eyes, lodgers blighted home interiors just as mixed land uses and traffic congestion blighted residential streets and suggested transitional social character (fig. 7.7).[37]

At the turn of the century, social workers and settlement house leaders also encouraged families to stop mixing social life, family relaxation, and work areas of the home. Most often, this had occurred in the crowded family kitchen—in tenements, then called a living room. Instead, the reformers urged immigrant families to invest in a formal parlor. As Lizabeth Cohen has stressed, separating kitchen and parlor functions met reform goals of creating sharp divisions between public and family interactions and of separating family members from one another within the house.[38]

Between 1870 and 1920, separation between family dwelling units and between commercial and residential land uses also became increasingly urgent imperatives. Jacob Riis decried that 80 percent of the

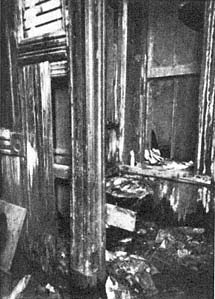

Figure 7.8

The possible horrors of shared

plumbing. A basement toilet room

in a New York City tenement.

crimes in New York City were perpetrated by individuals who had "either lost connection with home life, or never had any, or whose home had ceased to be sufficiently separate, decent, and desirable."[39] The word separate was notably first in his list of the necessary criteria for housing. The poor maintenance and overuse of shared toilets in slum residences led reformers to urge building codes that required private toilets and baths for each dwelling unit (fig. 7.8). The majority of architecturally oriented reformers saw dense urban housing as "promiscuity in human beehives." Decongesting the city called for smaller buildings, more open space, and spreading population out along suburban transportation lines. Interwoven with these desires was a growing preference for the open-lot house, set back from the street and from its neighbors, in place of the more urbane row building that nudged close to the sidewalk.[40]

Apartments and hotels, the critics said, also possessed the inherent flaw of shared entrances and halls. The term "apartment house," one committee said, was "simply a polite term for tenement." In the views of most reformers, store owners were no longer to live above the store, nor apprentices to live immediately adjacent to their work. To progressive reformers, any multiple dwelling inherently lacked "domestic quality"; moreover, the poor acoustical privacy of shared dwellings would intensify marital discord. There was, as one critic put it, "a short cut

from the apartment house to the divorce court."[41] Yet compared to such perceived threats to families, hotel life was held as an even greater hazard for single people.