Chapter Seven—

Hotel Homes as a Public Nuisance

Obviously, a good number of hotel residents and owners held positive views about hotel life. However, many opinion makers saw residential hotels as caldrons of social and cultural evil. At a national convention in 1905, the noted American housing reformer Lawrence Veiller condemned both residential hotel and tenement life for their serious social consequences:

The bad effect upon the community of a congregate form of living is by no means limited to the poorer people. Waldorf-Astorias at one end of town and "big flats" at the other end are equally bad in their destruction of civic spirit and the responsibilities of citizenship.[1]

Attacks like Veiller's on any "congregate form of living" had their historical roots in generations of middle and upper class complaints about urban density, mixture, and diversity—key aspects of hotel living. From the mid-nineteenth century to Veiller's time, negative ideas about downtown life had been enunciated and reinforced by literary commentators, housing professionals, and public officials. In the views of hotel critics, all hotels were suspect. Expensive hotels encouraged wasted lives, empty glamour, and rejection of traditional gender roles. These practices endangered the dominant culture of the middle and up-

per class and set poor examples for the working class. Since large proportions of the city's shiftless laborers, social misfits, thieves, and prostitutes lived in cheap hotels, reformers also assumed that hotel life must be an important part of the cause. By 1900, several generations of hotel criticisms were becoming woven into the housing reform opinions of the complex Progressive Era, which flowered from about 1890 to 1920.

Hotel Critics and Reform Ranks

The downtown environmental activists of the Progressive Era, like their colleagues in other parts of the movement, were generally self-appointed and wealthy businessmen—or their wives or minions—who volunteered their time and considerable talents for public good. These people were driven by equal parts of Protestant Christian charity, veiled self-interest, genuine noblesse oblige, and fear that their gigantic cities were out of control. The market-driven locations for industries and transportation had juxtaposed staggering numbers of new immigrant workers and ragged regions of noxious uses that overwhelmed earlier zones of middle and upper class residences, shops, and offices. Small-scale real estate and building practices seemingly had exacerbated slums, pollution, illness, and confusion about future land values (fig. 7.1). To the reformers, American privatism and boss politics were creating an unworkable city, one where not even the buildings of the wealthy could be guaranteed safe futures.

Given their personal class origins, most progressive reformers did not see low wages, uneven work availability, or industrial leadership as being primarily culpable for the urban chaos. In the building of cities, capitalism had merely gone too far. Like other Progressive Era figures, urban activists initially attacked the problems of downtown living as moral and cultural failures. They saw new ethnic, religious, and political subcultures as threatening to hard-won changes in polite family life. Along with the upsurges of American nativism during the nineteenth century came concerns about the serious personal and material culture cleavages between immigrant and native-born, poor and rich, unattached and family-tied, lawless and law-abiding.[2] Using a similar di-

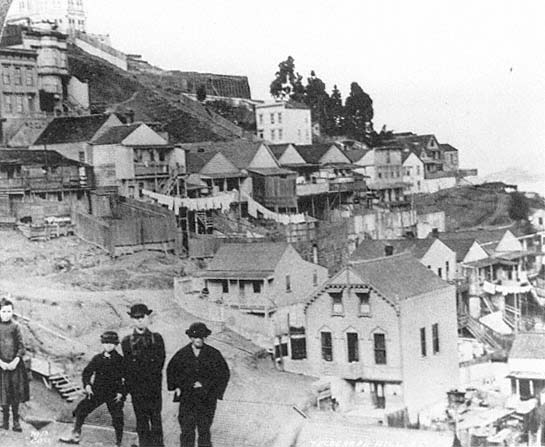

Figure 7.1

A Telegraph Hill slum with street urchins, ca. 1885. Scenes like these spurred San Francisco housing

reformers to action.

chotomy, critics of hotel life framed their housing attitudes with two extremes: the slums of downtown and the exclusive new zones of single-family houses at the edge of the city.

The reformers were convinced that stronger, centrally ordained, and better-enforced building rules would bring uplift to the lower class and civic betterment to the city as a whole. The new regulations and central planning would shore up the mainstream of the economic system and also maintain the power of the leading elite. Better housing meant not only better environmental health but also better social control. Promotion of material progress became a prime tool of social engineering.[3]

About hotel life, the mainstream reform opinions were usually negative and remarkably uniform, although progressive reformers were not a monolithic movement and often held contradictory views. A few fringe activists genuinely promoted hotel life.[4] However, several

basic tenets underlay the environmental activists' beliefs and behavior. First, the reformers shared good liberal arts educations; their views were stimulated by literary and social reform figures such as Thoreau, Emerson, Ruskin, and Carlyle; novelists such as Edith Wharton and Theodore Dreiser; and decades of journalistic travel accounts and city exposés, particularly those in the style of the pioneering New York journalist Jacob Riis. Second, in spite of occasional rhetoric to the contrary, the environmental reformers desired a monolithic culture. They admired individuality as exemplified by Thomas Edison or Theodore Roosevelt, but they did not widely value pluralism, heterogeneity, and diversity as related attributes.[5] Third, through most of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, they were imbued with environmental determinism, the belief that good environments would automatically create good people. Determinism also spurred belief in the obverse—that bad housing caused psychological, social, economic, and medical problems.

The ideas of scientific management and engineering efficiency, along with a great trust in physical solutions for social problems, also figured heavily in the intellectual bulwarks of progressive reformers. The early years of the 1900s were a golden age to focus on a problem, independently gather systematic data on it, proclaim oneself an expert, and thereby create a private or public post to solve it. Frederick Winslow Taylor and his followers were saving their industrial clients millions of dollars by doing systematic research and then finding the One Best Way to shovel coal or run grinding machines. Even social work from 1890 to 1917 aimed for universal attainment of a "normal standard of living"—a phrase that assumed an efficient One Best Way to live. That way, of course, was the way reformers themselves had lived in middle and upper class suburban families.[6] The activists rarely doubted that their own values were the best values. As one housing critic wrote, "Whatever home means for us, it means to others, for human nature is the same, and physical nature is the same, and mental laws are unvarying."[7]

As a solution to urban problems, reformers also promoted a centrally planned shift from the old city to the new city, from multiple use and mixture toward sorting and single use. One official group phrased it like this:

Industry, business, and home life may flourish in the same community if they are distributed according to an intelligent community plan. Without a plan, moral, sanitary, and economic slums are created.[8]

Within such value systems, hotels of all ranks came to be seen as prime elements of "moral, sanitary, and economic slums."

Concern with urban housing attracted the work of several overlapping and usually cooperating professional groups, most notably, housing experts, public health advocates, social workers, architects, and social scientists. Housing experts often took a leadership role, and foremost among them was Veiller, hired as a full-time housing official in New York in 1898. As the author of path-breaking model housing codes and later as an organizer and director of the National Housing Organization, Veiller was for twenty years the most important shaper of housing ideas in the United States. Nationally, a few dozen other experts formed the nucleus of consulting, research, writing, and lobbying about housing in the years before World War I. Their roster included traveling consultants like Carol Aronovici and housing philanthropists such as Alfred T. White and Robert W. Deforest.[9] Through professional meetings and personal contact, this small circle of housing experts knew one another well; most worked for strikingly similar committees of concerned business people. When Veiller preached that he was offended by the bad effects of the Waldorf-Astoria, he knew that his fellow housing activists agreed.

Groups of health reformers were similarly well organized. Their professions had gained great power with the public acceptance of the germ theory of disease and with discoveries in bacteriology; hence health reformers had the best ammunition to promote new housing laws (fig. 7.2). In the architectural realm, public health officers helped define minimums for room size, ventilation, and plumbing. Especially within the climate of environmental determinism, illness could be inextricably linked to places, and thus tuberculosis and pneumonia were "house diseases"; rooming house areas made women "drab, anemic, and disagreeably pathetic."[10] Social scientists and politicians also transferred powerful ideas of biological hygiene to the potentially dangerous concepts of social hygiene and moral contagion. Veiller borrowed from health reformers and stretched determinism even further:

Figure 7.2

Health poster from 1910. Hygeia,

the ancient Greek goddess of health,

is represented as sheltering the single-

family house, trees, and the baby

while she shuns the old city's

density, dirt, disease, and crime.

We know now . . . that poverty, too, is a germ disease, contagious even at times; that it thrives amid the same conditions as those under which the germs of tuberculosis flourish—in darkness, filth, and sordid surroundings.[11]

The historian Roy Lubove has noted that reformers devoted little thought to proving these elusive but seemingly self-evident relationships. Nonetheless, belief in public health models fueled influential housing opinions.[12]

By 1900, social workers, settlement house residents, and scientific charity organizers also participated frequently in the critique of hotel housing. These people taught immigrants the one "American" way of life, diffused new ideas of hygiene, and testified for better housing laws and new building projects. People with influential opinions included Edward T. Devine, a social work administrator, educator, and (after 1896) general secretary of the New York Charity Organization Society. Powerful figures such as Grace and Edith Abbott, Sophonisba Breckinridge, Florence Kelly, and Lillian Wald included housing reform in their labor research, settlement house work, and codification of social work. In the 1920s, Edith Abbott was named dean of the University of

Chicago's new School of Social Service Administration. In Boston, Robert A. Woods and his wife, Eleanor Woods, directed South End House, where settlement resident Albert Wolfe did his masterful study of rooming houses.[13]

Leading architects and planners of the Progressive Era often entered housing reform in their roles as designers of model housing and new public space, usually representing the desires of major landowners. A few architects, notably, Ernest Flagg of New York, combined housing activism with major commercial work. Influential citizens hired designers such as Daniel Burnham, Charles Mulford Robinson, and John Nolen to wrap real estate rejuvenation schemes in the classical City Beautiful garb of civic betterment.[14]

After 1900, university professors, often in the social sciences, became a more prominent influence among professional uplifters and the white-collar ranks of all the environmental reform groups. For several decades, Harvard sociologist James Ford summarized housing work. He was the associate director of Hoover's Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership in the 1930s. The University of Chicago was perhaps the most exciting and influential academic center of practical urban ideas and training. In addition to Hull House and the School of Social Service Administration, the university's sociology department engendered an entire school of thought. Robert E. Park, one of the most important American scholars of race, ethnicity, and urban life, in 1916 became the first president of Chicago's Urban League. Park and other faculty members like Ernest W. Burgess attracted graduate students such as Harvey Zorbaugh, Nels Anderson, and Norman Hayner—each of whom did important work on hotel housing. The first department of city planning eventually emerged at the University of Chicago, heavily influenced with the urban ideas of the Chicago school of sociology.[15] By the 1920s, professors often conferred the most powerful expert status on negative opinions about downtown living.

In hotel life, these overlapping sets of reformers saw challenges to the new urban order in at least three distinct realms: the well-being of the family, the development of the individual, and the safety of society as a whole. The following discussion traces each realm of cultural and moral critique from the mid-1800s through the Progressive Era itself and then beyond into the 1920s. The organization of time is in many short, parallel strands rather than one long cable. Each cluster of nega-

tive professional opinions about hotel life is presented with its own chronology.

Concerns for the Family

Nineteenth-century industries and businesses created work environments and work lives that were increasingly isolating, large-scale, and controlled by people distant from the family. In response, the role of home and family as the most important and nurturing sphere of life took on greater importance, especially to housing reformers. As Veiller put it, "Where there are no homes there will be no nation." In 1911, Dr. Langley Porter (the founding president of the San Francisco Housing Association) wrote that the "health of the individual, physical and moral, and health of the community, physical and moral, both depend in no small degree on the dwelling in which the individual is housed." People who felt (as another activist put it) that home and family were the "crucible of our happiness" saw the notion of people living alone, or family groups living in uncharacteristic ways, as a clear danger to several aspects of the Victorian middle-income family.[16]

Undermined Domestic Roles and Rituals

Women who lived in hotels—particularly those residents of palace and midpriced hotels who could afford the alternative of a single-family house—ran the risk of becoming spoiled by caravansary comforts. They also inevitably violated the Victorian requirements of true womanhood—being a proper mother and an active homemaker.[17] In 1857, the editors of Harper's Weekly declared that hotel women were "rapidly becoming unfit not only to be mothers, but to be wives, and members of society at all" (fig. 7.3). They could "neither work, nor talk, nor cook, nor make a bed." Worse yet, they spent "their whole life in gossiping with people of both sexes who are as idle as themselves."[18] Early critics also warned that the inappropriately lavish habits and empty materialism learned in expensive hotels would follow young couples into their mature years.[19] In 1905, Edith Wharton saw the fulfillment of such prophecies. She characterized fashionable New York hotel women as socially objectionable:

Figure 7.3

This reposing room in a Turkish bath, about 1904, typified the self-indulgence

and empty lives that hotels made too easy for women of wealth.

[They were] . . . wan beings as richly upholstered as the furniture, beings without definite pursuits or permanent relations, who drifted on a languid tide of curiosity from restaurant to concert hall, from palm-garden to music room, from "art exhibit" to dressmaker's opening.[20]

It was all, Wharton said, a "vast, gilded void of existence." Other commentators found midpriced hotels less gilded but still empty. In 1923, hotel maids told Hayner that life at a midpriced hotel "made bums out of women." Their days consisted of sleeping until noon, shopping, playing bridge, taking beauty naps, dressing for dinner, and going out in the evening. One maid called the late-sleeping women "sundodgers."[21]

Interior decorating—assembling the middle-income family's material individuality—relied particularly on the mother. Critics wrote that a hotel mother could not "create that atmosphere of manners and things around her own personality, which is the chief source of her effectiveness" and her power over her husband and the development of her children.[22] Data in the 1920 census alarmed Bertha Nienburg, who wrote that Rochester, New York, had 11,500 married women (out of 74,000 total) who were eating at restaurants or living with relatives and thus not keeping house. These women, said Nienburg, may have been "succeeding in their function as guardians of the family," but they were

"not contributing to the permanence and stability of civic life through the maintenance of homes."[23] An unhappy woman who had lived in a hotel concluded that "the only endurable kind" of day to have while living in a hotel was a "day busy elsewhere."[24]

Ironically, "being busy elsewhere" was exactly why hotel life appealed to many women of the middle and upper class. Part of the hotel's threat to the true cult of womanhood was that it freed women with nontraditional lives—those who had paid vocations (as doctors, teachers, or secretaries) or active volunteer careers (with charities or other organizations)—from the roles of decorating, entertaining, and doing little favors for their families. Inasmuch as such women threatened the dominant culture, their hotel homes were a threat as well.

Also prominent in the sins of hotel life was its reputation for breaking the ritual and privacy of the family dinner table. William Dean Howells said that for the proper family, private dining was the "moral effect of housekeeping." At the table, or in the parlor after meals, the ideal family was supposed to linger for conversation, companionship, and reading or embark on spontaneous family excursions. Public dining flaunted the model family meal supervised by the mother, presided over by the father, and attended by children at their accustomed chairs receiving instruction (figs. 7.4, 7.5).[25] To the 1903 editors of Architectural Record , communal dining was "the consummate flower of domestic irresponsibility, . . . the sacrifice of everything implied by the word 'home.'"[26] In restaurants or in boardinghouses, regular seats could not be assigned, and parents could not discipline their children without feeling public scorn. Families did not even have to eat at the same time. If they did eat together, they often scattered after the meal: father to the lobby to talk with men about business or politics, mother to a bridge party, daughter to a dance, and son to the billiard room. Hotels presented almost no friction of distance to retard this family dispersal, while suburban settings imposed a great deal of such friction. Burgess put it in the terms of an urban sociologist: the "small family group in apartment houses and residential hotels" was "the most notorious illustration of effectual detachment from the claims of kinship."[27] The lack of control in the dining room extended to the rest of the hotel home. In common halls or public lobbies, strangers and chance acquaintances had ready access to children. Mothers could not strictly control what their children saw in daily life.[28]

Figure 7.4 and 7.5

Two of a series of 1871 Harper's Weekly cartoons by Thomas Nast comparing hotel and home life.

Left , the tranquil and protected family dining room; right , a rough and noisy dining room in a

mid-priced hotel of that period.

Also threatening the mainstream role of wives was the fact that hotels made possible a cultured, civilized life for men without the aid of a woman. To be sure, cheap lodging houses did little to substitute for women's care. So, too, the stereotypical homeless or single man was a nasty, gruff brute who proved how much men needed the civilizing influence of a home with a woman to take care of him (fig. 7.6). However, hotels in the better price ranges could provide domestic care as well as, or better than, a woman could. In some cases, then, the maxim "what every man needs is a good woman," became "what every man needs is a good hotel ."[29] Hotel life not only threatened to spoil men and women for predetermined roles but also threatened to erase the roles themselves.

Individualism versus Marriage and Child Rearing

Observers of hotel life saw resident pipe fitters, maiden aunts, and mobile professional people as abnormal for several reasons. Beginning as early as the 1840s, critics worried that hotel life delayed marriage for single residents; for married couples, hotel life also seemed to delay child bearing.[30] According to Wolfe in 1906, the distractions of living downtown rendered people selfish and self-centered and emphasized "the individual life at the expense of the family and the home." Marriage became "too great a sacrifice"; children meant "expense and trouble and constant attention and 'being tied down at home.'" The American standard of living, he continued, was becoming an individual standard rather than a family standard. Roomers learned very soon the art of

Figure 7.6

"How We Sit in Our Hotel Homes." This engraving from an 1857 Harper's Weekly story about

living in New York City hotels showed how much men needed traditional home life.

"seeking everywhere the greatest individual comfort at the least expense.[31]

Hotel living did imply childlessness. On the one hand, hotel and rooming house zones had the lowest birthrates for most cities and stood in sharp contrast to home-ownership areas with their high marriage rates and birthrates. In 1900, 95 percent of those owning houses in San Francisco were married, and 81 percent had children. Looking at these phenomena, social scientists and reformers did not assume market sorting as an explanation, that is, that unmarried childless people simply chose hotel housing. Instead, the reformers concluded that hotel housing caused the antifamily phenomena.[32] Based on the long history of problem children in hotels, housing professionals and hotel residents agreed that the environment suited children poorly.

To social arbiters, worse than delayed marriage or child bearing was never marrying at all. About one-tenth of the American population typically has never married, and as much as one-third of New York City's population lived alone in 1930. Yet, through the 1950s, Americans widely considered the condition of being unattached as either temporary or abnormal. The premier housing scholar, James Ford, wrote that having few contacts with married couples, children, and people

outside one's own age and sex group tended to make the lives of hotel people seem aberrant. Wolfe spoke of marriage "rescuing" tenants "from the rooming house world and its sophisticating, leveling, and contaminating influences." Chicago social workers visited groups of workingmen who were sharing apartments and were surprised that the men were "extremely friendly," as if hospitality and friendliness were found only in family households.[33]

The relative absence of children was responsible for much of the unnatural character of single-room districts. Zorbaugh, the Chicago sociologist, felt that children were the real neighbors; childless districts therefore lacked a key catalyst of neighborly feeling. Sociologists noted that children forced adults to plan and hope for the future and to consider other-directed action. While child-filled tenements sparked hope (or its frustrated form of outrage), hotel housing rarely evinced either.[34] In order for there to be a proper neighborhood for children, the majority of American middle and upper class families also typically demanded yards or gardens. The reliance on yards as social separation zones related to another cluster of hotel critiques.

Demands for Separation and Low Density

For centuries, wealthy burghers in Europe lived only a floor or two away from their place of work and from their poorest employees, apparently with no significant contagion of poverty. By 1900, in America, such density, mixture, and adjacency were becoming highly suspect in the view of reformers. Critics chided comfortable hotel families who lived in suites of rooms for having a lack of privacy. Residents in cheaper hotel types were criticized for living with too little space per person and for mixing disparate activities in the same room.[35] Reformers blamed some rooming house crowding and mixture on un-American housing standards brought by immigrants from southern Europe, where large families often lived in one or two rooms. Social workers also deplored as "a demoralizing lack of privacy" the European habit of having the same bedroom occupied by grown brothers and sisters. Hull House social workers called a married couple and a child living in one or two rooms an "irregular method of living." What was combined in one room, they said, should have been separated and sorted out in "parlor, bedroom, clothes closet, dining room, kitchen, pantry, and even coal shed." Building inspectors

Figure 7.7

Pathological proximity. A rag picker and a middle-class

woman, at such close quarters, emphasized the

social schisms of urban life in 1875.

ruled that cooking in bedrooms caused vermin problems, dirtied bedding, and problems of inadequate ventilation of cooking odors.[36]

The fear of mixture and the desire for separation also manifested themselves in critiques of the "lodger evil"—the practice of families taking in unrelated men or women as renters. Lodgers often shared family bedrooms. Also seen as unwanted mixture were the "invasions" of housing districts by corner grocery stores, multiple dwellings, small factories, and repair shops. In reformers' eyes, lodgers blighted home interiors just as mixed land uses and traffic congestion blighted residential streets and suggested transitional social character (fig. 7.7).[37]

At the turn of the century, social workers and settlement house leaders also encouraged families to stop mixing social life, family relaxation, and work areas of the home. Most often, this had occurred in the crowded family kitchen—in tenements, then called a living room. Instead, the reformers urged immigrant families to invest in a formal parlor. As Lizabeth Cohen has stressed, separating kitchen and parlor functions met reform goals of creating sharp divisions between public and family interactions and of separating family members from one another within the house.[38]

Between 1870 and 1920, separation between family dwelling units and between commercial and residential land uses also became increasingly urgent imperatives. Jacob Riis decried that 80 percent of the

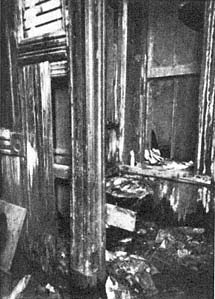

Figure 7.8

The possible horrors of shared

plumbing. A basement toilet room

in a New York City tenement.

crimes in New York City were perpetrated by individuals who had "either lost connection with home life, or never had any, or whose home had ceased to be sufficiently separate, decent, and desirable."[39] The word separate was notably first in his list of the necessary criteria for housing. The poor maintenance and overuse of shared toilets in slum residences led reformers to urge building codes that required private toilets and baths for each dwelling unit (fig. 7.8). The majority of architecturally oriented reformers saw dense urban housing as "promiscuity in human beehives." Decongesting the city called for smaller buildings, more open space, and spreading population out along suburban transportation lines. Interwoven with these desires was a growing preference for the open-lot house, set back from the street and from its neighbors, in place of the more urbane row building that nudged close to the sidewalk.[40]

Apartments and hotels, the critics said, also possessed the inherent flaw of shared entrances and halls. The term "apartment house," one committee said, was "simply a polite term for tenement." In the views of most reformers, store owners were no longer to live above the store, nor apprentices to live immediately adjacent to their work. To progressive reformers, any multiple dwelling inherently lacked "domestic quality"; moreover, the poor acoustical privacy of shared dwellings would intensify marital discord. There was, as one critic put it, "a short cut

from the apartment house to the divorce court."[41] Yet compared to such perceived threats to families, hotel life was held as an even greater hazard for single people.

Hazards for the Individual

The lives of single people in hotels invoked repeated reform critiques. The youth culture and recreation zones in rooming house districts were causes of alarm. Yet overarching all was the lack of parental and neighborly supervision of the sort that critics assumed to exist in traditional small towns. Ironically, some hotel residents felt too closely watched in hotels; they complained about feeling "very much in the public eye, . . . living in public, eating in public, and all but sleeping in public." A writer who had lived in a fifty-four-room hotel for thirteen years said she overheard servants having frequent conversations about guests; furthermore, she said, each guest was "carefully watched by certain 'old tabbies'" who lived there.[42] Yet, in the eyes of late Victorian and Progressive Era observers, this hotel surveillance packed too little social pressure to counter the environment's sexual temptations or its professional crime.

Sexual Immorality and Improper Recreation

According to mainstream reform views, the potentials for personal immorality—frequent sexual liaisons outside marriage—loomed much larger for people living in hotels than for people in suburban houses. The reasons seemed clear: in hotels, members of the opposite sex lived on the same hallways, had the right to visit one another's rooms, and could come and go quietly. New people moved in weekly or monthly. Sexual immorality, in fact, was the problem that prompted the settlement house resident, Albert Wolfe, to publish his exhaustive 1906 study, The Lodging House Problem in Boston . He decried many evils of rooming house life but identified sexual immorality as the "darkest aspect." Reformers in many cities described unmarried couples living together as major evidence of a "general loosening of moral texture."[43] Each time a landlady said, "What my tenants do is their own business as long as they pay their rent on time," she had substituted commerce for traditional social controls. Rooming houses, others said, had lost the "personal element in life."[44]

Along with their focus on sexual offenders, reformers also focused on the mixture of wayward souls with other, impressionable people. Hotels and rooming houses, said Wolfe, exuded an "atmosphere of moral laxity" that was dangerous for virtuous country people who had been thrown into the deep water of city life. "Consciously or unconsciously, the influence of imitation will be at work," he wrote. "If we stay in Rome long enough, we do as the Romans do."[45] Matrons in San Francisco concurred with Wolfe. The housing danger for a single girl in the 1920s was no longer the white slaver but the gradual breaking down of spiritual and moral standards as a result of improper surroundings and companionship. The cheapest residential hotel rooms, the matrons added, caused the most overcrowding, worst sanitation, and greatest "moral strain."[46] The high incidence of venereal disease among roomers and the number of abortion clinics in rooming house neighborhoods underscored concerns about sex, as did the belief that the temporary sexual liaison was "one avenue through which the prostitute class, both of men and women," was recruited.[47]

Prostitutes did live in some hotels, and they could both learn and practice their trade there (fig. 7.9). The shadier rooming houses associated with beer gardens and commercial amusement gardens were almost sure to be places of assignation. In 1915, housing inspectors in Stockton, California, wove their concerns about prostitution into a survey of rooming houses located over saloons:

Women openly solicit in booths in the saloons and take men to the rooms upstairs. In one house the inspector observed that every man accompanied by a woman was asked whether the room was desired for "only a little while or for the night."[48]

In other cities, larger hotels also came in for criticism because prostitutes mixed too easily with tenants. Reformers reiterated that in hotels, both men and women lived next door to "fearful possibilities."[49]

Since people of the same sex routinely shared a hotel room (and sometimes shared a bed) without comment, homosexual couples blended without notice into the upper ranks of hotel life. But in cheap lodging houses and missions, where visual and acoustical privacy was difficult, social investigators made careful note of homosexual solicitation and activity. The sociologist of hobo life, Nels Anderson, reported that homosexual practices among male migrant laborers were fairly

Figure 7.9

Prostitute thieves plying their trade with the help of an elegant hotel room.

A cautionary view from the National Police Gazette , 1879.

common. Although he said they were not more frequent than in other all-male situations—prisons, the army, or the navy—these relationships concerned the parents of adolescent boys doing migrant work.[50] Such realities added to the sexual taint of hotel life.

More prevalent than sexual immorality were the perceived dangers of drinking, dancing, café life, and cheap amusements. Together they created another side of the "bright light district" and rooming house youth culture that affronted reformers (fig. 7.10).[51] Similar problems, most vivid in the elite hotels, were associated with all types of hostelries. Elbert Hubbard, author of the popular A Message to Garcia and an enthusiastic booster of Craftsman-style bungalows, characterized the residents of expensive hotels as "a gilded, gabby gang of newly gotten rich, or the offspring of such." The flashy hotels were places "where the vampire finds her hunting-ground, and the riot of the senses is complete; where flunkies flunky without ceasing, and the parasite is at

Figure 7.10

Signs of dangerous commercial and residential

mixture, 1936. This Kansas City drovers' hotel

advertises housing and beer at the same location.

home."[52] The Saturday Evening Post tersely called hotel life "the time killer industry." Chicago social workers acknowledged surprise at encountering families that seemed to like living in furnished rooms and rooming houses because they desired "the excitement that can be found in the rooming-house neighborhoods."[53]

Temperance crusaders aimed their hostility at hotel operators as well as at saloon keepers. The housing expert Carol Aronovici, in a study of cheap lodging houses in St. Paul in 1917, took pains to photograph empty liquor bottles in the rooms. During Prohibition, some hotels engaged directly in bootlegging; at better hostelries, the bellmen often sold or gave telephone numbers for obtaining bootleg liquor. In 1921, the highly publicized death of a drunken woman during a party given by Roscoe (Fatty) Arbuckle in San Francisco's St. Francis Hotel gave the term "Arbuckle party" to any wild hotel room celebration.[54]

The volatile combination of fast and close dancing, alcohol, and the absence of chaperones spelled trouble to reform-minded people wherever it occurred—in a grand hotel or in a cheap dive. In 1883, a Methodist church in San Francisco listed dancing twice among its list of sinful city amusements. Indeed, many of the cafés frequented by hotel residents also featured daily dancing and introductions of men and women by café employees (fig. 7.11).[55] Some palace hotels scheduled weekly and then daily tea dances. In 1917, a concerned citizen published a newspaper article entitled "Afternoon Teas First Step Toward

Figure 7.11

Postcard view of the Cave Cafe and Grill, near San Francisco's rebuilt

Barbary Coast, ca. 1920. The back of the postcard promised

"something doing all the time"—exactly what worried

reformers about unchaperoned social life.

Depths; Evolution of Good Girls to 'Flappers' of the Bright Lights Is Subtle Transition."[56]

Pathological Proximities and Isolation

Another, less visible hazard of hotel life, according to critics, was its potential for leading to a life of crime. Reformers saw this risk particularly in cheap lodging houses, where young people might mix with the most hardened criminals. The chief of New York's secret police branded the laborers' hotels of the Bowery as "nurseries of crime." He claimed that the peril peaked when a young man was nearly broke and he checked into a 15-cent lodging house:

[The young man is then] ready for the tempter whom he finds waiting for him there, reinforced by the contingent of ex-convicts returning from the prisons after having served out their sentences for robbery or theft. . . . In nine cases out of ten, he turns out a thief, or a burglar, if indeed, he does not sooner or later become a murderer.[57]

To his credit, the police chief saw lack of work as the root cause of this progression, but this was lost in related discussions. In a conversation with Riis, a New York police court justice vowed that the 10-cent lodging houses more than counterbalanced "the good done by the free reading room, lectures, and all other agencies of reform." He continued that "such lodging houses have caused more destitution, more beggary and crime than any other agency" he knew.[58] In the twentieth century, Los Angeles police routinely searched for law offenders in the cheap hotels

Figure 7.12

Suspicious isolation and improper material life.

The caption for this photograph in the 1919

report of California's Commission on Immigration

and Housing read, "Is the housing problem

merely a problem of houses ? Can we expect

this man to be 100 percent American?"

and rooming houses near the railroad station. Raymond Chandler's detective character, Philip Marlowe, repeatedly visited hotels "whose clerks were 'half watchdog and half pander' and where nobody except Smith or Jones signed the register."[59]

A different but also negative side to the illicit adjacency of hotel life was the friendless life also possible there: the painful isolation for those who did not want to be alone, or those who were pathologically withdrawing from human company (fig. 7.12). According to one hotel resident, a hotel filled with people having fun could be "the most lonely place in the world." Rooming house residents with no friends in the area could write poignantly about the "cramped and awful loneliness of a hall bedroom." Young people who did not frequent dance halls or lively cafés but passed them frequently were constantly reminded of their own solitude.[60]

Zorbaugh—whose personal loneliness during his Chicago fieldwork added to his sharp distaste for hotel life—said that hotels carried individualization "to the extreme of personal and social disorganization." Rooming houses "were a world of atomized individuals, or spiritual nomads."[61] As proof, Zorbaugh presented the following statement

of a young rooming house woman who had moved to Chicago from Emporia, Kansas, for fervent but futile study as a violinist:

One gets to know few people in a rooming-house, for there are constant comings and goings, and there is little chance to get acquainted if one wished. . . . There were occasional little dramas—as when a baby was found in the alley, and when the woman in the "third floor back" took poison after a quarrel with her husband . . . when the halls and the bathrooms were the scenes of a few minutes' hurried and curious gossip. But the next day these same people would hurry past each other on the stairs without speaking.[62]

Whether or not single-room housing caused such isolation, lonesomeness was part of the territory.

Frequently published reports of suicides kept vivid the public image of pathological isolation in hotels and rooming houses. One hotel manager explained that after gaslights and gas heaters became standard equipment, suicide in hotel rooms was more common; suicide with gas was easier than using a gun or a razor blade.[63] Dozens of novelists set suicides in single-room housing. Hurstwood, the erstwhile husband in Dreiser's Sister Carrie , lives his last months in cheap rooming houses where he "toils up" the inevitable "creaky stairs." In a tiny room with gas jets "almost prearranged" for what he intends, he eventually kills himself with a final antisocial phrase, "What's the use?"[64]

Threats to Urban Citizenship

Suicide and individual isolation worried Progressive Era housing reformers, but more troublesome was the isolation of hotel residents as a group. Even when they were not acting en masse in some political agitation, hotel people seemed to be forming subcultures that deepened the social schisms of the time and weakened the cultural hegemony of the middle and upper class. Reformers saw these dangers as an assault on the urban polity as a whole.

Insufficient Materialism

By 1900, most Americans had settled into the belief that form of tenure—owning versus renting—could be used reliably to discern someone's social position in much the same way that race, income, occupation, and education were used. In interviews, poor house owners in Chicago said that owning a home made them "real

Americans" and gave them a means of achieving personal control over their world.[65] Since so many Americans anchored their personal and civic identities to their homes, reformers saw those who did not (or could not) as insufficient, deviant, or unhealthy. In short, renters were second-class, or perhaps third-class, citizens. Early observers warned that the rental aspect of hotel life's "dissipation" would engender "a distaste for steady and persevering application to anything."[66] Housing policymakers (property owners themselves) firmly agreed that both apartments and hotels would breed bad citizenship. In 1910, Veiller said this about apartment renters:

It is useless to expect a conservative point of view in the workingman, if his home is but three or four rooms in some huge building in which dwell from 20 to 30 other families, and this home is his only from month to month. . . . Democracy was not predicated upon a country made up of tenement dwellers, nor can it so survive.[67]

California housing activists concurred that the home, not rental property of any kind, was "the bulwark of good citizenship." Other California critics complained that if migrant workers saved money, it was only to send the money back home rather than invest it in the local economy. The migrants therefore had little desire to improve their living quarters.[68]

In an otherwise path-breaking book on urban housing, the influential planner Henry Wright flatly explained multiple-family homes as a result of irresponsibility:

[The inception of the apartment house] was brought about by the vaguely defined need of families whose habits were of a semi-transient nature, or those who did not care to assume the responsibilities of the independent house, and yet neither desired nor could afford the luxury of hotel life.[69]

Wright was one of many housing activists to carry Veiller's ideas into decades of later practice.[70]

For the business elites who directed Progressive Era housing reform, the bonds of rootedness and civic responsibility were woven out of mortgage payment receipts: personal financial interest in city real estate. Home ownership guaranteed accumulation of goods through thrift and self-denial. For some analysts, renters also undermined the

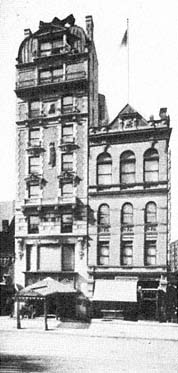

Figure 7.13

A building considered

dangerous to civic virtue.

A typical small apartment

hotel in New York City, 1903.

stability of centralized bank and mortgage control because they paid scattered individual landlords.[71]

Within the realm of renters, a distinction between hotel dwellers and apartment dwellers arose over the amount of personal possessions needed for a proper American home. Unlike apartment dwellers, hotel residents rented both their space and their furniture (fig. 7.13). To social observers and public policymakers, this unrootedness crossed the last boundaries of civic propriety. Official rhetoric required citizens to own furniture and dishes as the minimum evidence of stability and civic worth. For Wolfe, household goods and furniture were "those last anchors of men and women to a sense of ownership and permanent interest in a fixed abode."[72] Furniture was an important minimum for Edith Abbott, too. The great evil of the rooming house, she asserted, was neither landlord profit (as some reformers said of tenements) nor sanitary danger. Instead, it was "the degradation that comes from a family living in one room with broken, dilapidated furniture, without responsibility or a sense of ownership, . . . [with] nothing of their own."[73]

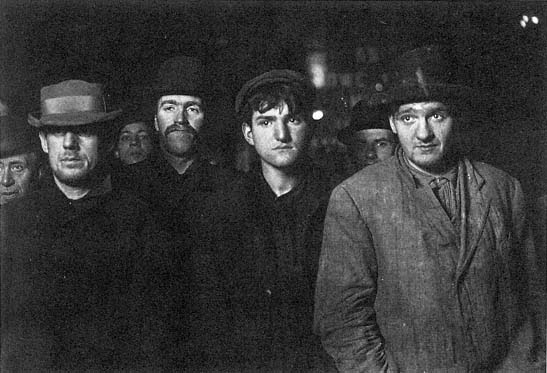

Figure 7.14

Citizenship not encouraged here. Part of a winter bread line at the Bowery Mission in New York City,

photographed by Lewis Hine in 1906.

For hotel and rooming house residents, the American dream of owning one's own house, yard, and furnishings often did not match the necessity of mobile careers and occupations. That mobility itself constituted another realm in the cultural threats of downtown living.

Mobility and Vagrancy

Virtually no one wanted hoboes and other overtly mobile people to be citizens of the city. Officials and the public automatically assumed the worst about hoboes (fig. 7.14). "The doctrine that the American tramp is a pariah and that he ought to be kept such is not often formulated so bluntly, but it embodies the underlying doctrine of the American method in dealing with the tramp," wrote William Stead in 1894 in If Christ Should Come to Chicago . Stead accurately reported that the bum was generally and unfairly seen as "outside the pale of human sympathy, . . . an incorrigibly idle loafer, a drunkard, a liar, and a reprobate."[74] Johanna Von Wagner, a Progressive Era tuberculosis inspector in California, candidly expressed the pa-

riah view as she described the residents of San Francisco's cubicle hotels in 1913:

The inmates of these places are human wrecks, old and young, diseased or habitual drunkards; others have failed in the struggle for existence, and [there are] those who from the beginning were never able mentally or physically to compete with their fellow men, their condition making it all the more urgent that they be compelled to live in a more sanitary environment.[75]

To Von Wagner and the general public, the casual laborer's style of life was not only alien but abhorrent, vagrancy and travelers having been mistrusted by Europeans for centuries. Single hoboes and casual laborers were not only poor and unmarried but also violated even more basic American values: cleanliness, sobriety, self-control, steady employment, material possessions, and commitment to home and family. Where "pariah" was too honest a term for such people, writers substituted the term "homeless man." By 1900, vagrancy as a legal term also meant begging, loitering, street walking, and indigence. Chicago School sociologists did occasionally associate creative social change with mobility. More often, however, they linked mobility to vice districts, bright light areas of the city, divergent types of people and activities, and general social disorganization.[76]

Hoboes were not the only mobile people to be mistrusted, however. Robert Park conflated "the hoboes, for example, and the hotel dwellers" as "unsettled and mobile . . . [and] stabilized only on the basis of movement, tribal organizations, and customs."[77] In 1915, in his famous article, "The City," Park used hotel life as a metaphor of metropolitan social disintegration:

A very large part of the population of great cities . . . live much as the people do in some great hotel, meeting but not knowing one another. The effect of this is to substitute fortuitous and casual relationships for the more intimate and permanent associations of the smaller community.[78]

Two generations of Chicago students applied Park's concepts. Ernest Mowrer wrote that the "emancipated" families in hotels had "casual or touch-and-go" relations with their neighborhood. Zorbaugh decried the social breakdowns in Chicago's cheap rooming houses as well as in expensive Gold Coast apartment hotels. The Gold Coast, he claimed, was merely a "location," not a neighborhood. The existing solidarity

was one of "caste rather than of contiguity." In rooming houses, he said, "there is not even gossip, no interest, sentiment, and attitude which can serve as a basis of collective action. Local groups do not act. Local life breaks down. . . . The last vestige of community has disappeared."[79]

Park's student Norman Hayner put the worst possible construction on mobility in his 1920s study of hotel life. For instance, he interviewed a well-paid man and his wife, married four years, who moved often because the man established new sales franchises for electrical appliances. Hayner denigrated them as a "childless tramp family moving about from apartment to hotel and never staying in one place more than four or five months."[80] Edith Abbott, in her book summarizing twenty-five years of social work in Chicago, sympathetically presented immigrants and blacks as hapless victims. However, for the families living in furnished rooms—overwhelmingly American-born white people—she displayed obvious disgust and exercised her most invective prose. Such families were "an objectionable class [that is] unstable, irresponsible, and shiftless," for which little could be done.[81] To professors of the Chicago School, moving frequently undermined the power of neighborhoods, and the areal neighborhood was an essential element, if not the essential element, in the definition of community. This definition took long-term root at the core of the city planning profession and of suburban design policies.

Mobility meant not only a poorly formed community but also apathetic and corrupt voters. Community fund solicitors and census workers complained that clerks at polite hotels automatically intercepted their attempts to canvass hotel residents. One census director said that hotel people were "so bent on having a good time that duty to the city means nothing whatever to them."[82] Although one study found that a third of Chicago's permanent rooming house residents voted, a precinct captain from nearby complained that it was "useless to try to get the people from the rooming houses to go to the polls."[83] Proprietors of some large boardinghouses became notorious for organizing their tenants in political-machine voting scandals. In New York City, both major parties regarded residents of cheap lodging houses as potential paid voters.

When hotel residents were independently organized and active, they became a community that menaced middle and upper class order. San Francisco's South of Market area saw violent workers' outbursts in the

Figure 7.15

The howling wolves of urban disease assailing the suburbs. This health poster of 1910 promoted

the protective wall of health reform. The original caption read, "How high is the wall in your town?"

1870s and in 1885, 1891, 1893, and 1902.[84] The national march of Coxey's Army in 1894, reinforced by the later organizing attempts of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1912 through the 1930s, proved to the public that rooming house and lodging house people could act as a community. Even when laborers were not marching, the presence of Socialist bookstores and Marxist lecturers and devotees in the single laborers' zone reminded observers of nascent unrest.[85] No matter what outside observers made of hotel patrons' political leanings, hotel districts also represented reservoirs of yet other hazards.

Risks to Urban Real Estate and Biological Health

At a very practical level, the fire and health menaces of cheap downtown hotels worried downtown landholders. Inspection reports and newspaper exposés repeatedly spotlighted old, poorly built, and badly managed hotels as perilous firetraps. Some rooming and lodging houses had no fire escapes; some had hallways and stairways too blocked or too narrow for egress. In other buildings, managers had padlocked the fire doors. A typical fire report in 1924 concerned a three-story wooden hotel in Los Angeles where thirty-five people died because of inadequate and defec-

tive fire escapes. Officials routinely reminded builders that cheap wooden hotels threatened the adjacent buildings, the entire neighborhood, and the hotel inhabitants.[86]

Fire dangers paled next to the health risks that cheap hotel areas represented to reformers (fig. 7.15). A California state housing report on San Francisco lodging houses complained that since the buildings housed thousands of "irresponsible" men "careless as to their general personal habits and cleanliness," they presented "an ever constant danger to the health of the entire city." The report stated that shared toilets and baths, especially when poorly maintained, spread diseases among all the tenants; the constant moving from lodging to lodging carried infection to other buildings. Inspectors declared that lodging house rooms posed an additional health risk: they cited vermin-covered beds and blankets reeking with filth and soaked with wine. In most San Francisco lodging houses, sheets were changed (at the most) twice a week—not necessarily for each new occupant of a room; only one-fourth of the establishments ever fumigated their blankets.[87] Von Wagner, the tuberculosis inspector, vividly summarized the dangers:

The cheap class [of hotels] with ten to twenty-five cent beds, are not only breeding places for various diseases, but also centers of infection, especially tuberculosis. We know from past history that plague, cholera and smallpox originated in cheap lodging houses. Therefore, they should be eliminated. They are all unfit for human habitation.[88]

Von Wagner also shuddered at the use of common towels and common drinking cups, holdovers of nineteenth-century hotel practices. Notably, because of the earthquake and fire of 1906, the San Francisco buildings in question were less than ten years old at the time of these descriptions. Conditions in other cities were often worse.

More than any other critique, enforcement of fire and health codes brought reformers into early face-to-face conflicts with building owners. These confrontations revealed deep schisms in progressive reform. In their family tenement literature, activists like Veiller, Park, and Abbott attacked the greed of individual landlords who often held relatively small and scattered properties. However, when the reformers wrote about hotel problems, they mentioned landlord greed much less and argued more against hotels on cultural and social grounds. In the search for the root of the hotel housing problem, the tenants and their

culture were seen as guilty.[89] It was easier for reformers to nominate themselves as caretakers of culture than to question the property industry.

Challenging culture instead of profit or class was not necessarily dissembling behavior on the part of the housing activists. The attempts to establish new ideas about centralized control of land use and building types were openly fought to preserve property values that matched those of downtown or suburban landowners. One of the ironies of the Progressive Era was that reformers fought monopolies but often helped big business as well. Small-scale downtown owners or slumlords rarely had the ear of the reformers, while big landholders with prominent downtown blocks of land were often reform allies and charity organization directors. Concerns about moral problems thus merged easily with concerns about real estate values without seriously challenging the American city's established power structure.[90]

Hotel Homes as a Public Nuisance

Like the reformers' ironic positions on real estate values, the negative hotel housing opinions voiced by literary critics, housing activists, health officials, and social workers were not without their internal contradictions and exceptions: hotel housing did not provide proper individuality and personal expression, yet it fostered selfish individualism; hotel housing was pathologically isolating, yet it was not sufficiently private; no one supposedly met anyone in hotels, yet lodging houses were meeting places of great danger. Outright hypocrisy characterized other critiques: amusements enjoyed by wealthy people (billiards for men after dinner; cotillions for all) were wrong in commercial settings or when enjoyed by wage laborers and families struggling to enter the middle and upper class. Some critiques were simply myopic: the people who saw the pathologies of rooming houses rarely mentioned the parallels in other housing types, such as the breaches of sexual mores at weekend house parties of the wealthy or elderly widows pathologically isolated in middle-income suburban houses.

A few social commentators did understand and accept the hotel population's nontraditional ways of living. The Chicago sociologist Day Monroe was one of these exceptions. In a study of Chicago families she noted that "certainly fewer than 20 percent" of the people living in hotels exemplified the supposed "social waste, unproductive leisure,

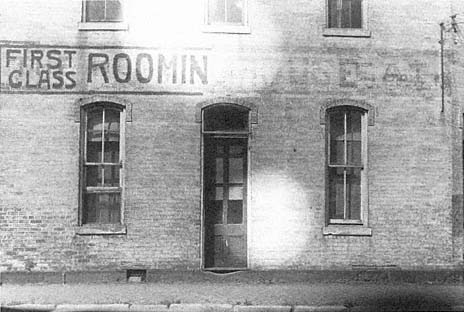

Figure 7.16

Rooming house in Lancaster, Ohio, 1938. As a photographer, Ben Shahn caught the

irony of a single worker's life-style labeled "first class."

or even family disorganization" that others automatically associated with hotel life. The majority of women living in hotels had good reasons for being there and represented social well-being, Monroe said.[91] Charles Swanson wrote his doctoral dissertation on the social backgrounds in Lower West Side districts of Manhattan, areas analogous to the Chicago rooming house area analyzed in Zorbaugh's Gold Coast and Slum . Swanson failed to find the social pathologies described by Zorbaugh. He saw "no area of anonymity, of desolation, loneliness, and lost personalities." He said that quite the contrary seemed to have been true, since Bohemianism strictly tabooed such qualities.[92]

Nonetheless, with such occasional exceptions, after 1890 the case for hotel life was rarely stated forcefully or officially. By the 1920s, the case against hotel housing options had successfully been assembled. Stated most simply, to its critics the continued existence of hotel life worked against the progress of the grand new city. In the biological analogies of the day, the residential hotel buildings themselves served as incubators of old-city pathologies. For the reformers working on the new city, single-room dwellings were not a housing resource but a public nuisance (fig. 7.16).

In 1910, Veiller published a major model housing law to help promote such legislation throughout the United States. For each section of the proposed law, he provided capsule explanations. In his explanation

for the definition of "tenement," Veiller was careful to emphasize the following point:

[The definition of tenement] does not include hotels nor lodging houses. It should not do so. [***] The problems of the common lodging house occupied by homeless men or homeless women are totally different from the problems of the tenement house occupied by families. The two should not be confused.[93]

The asterisks inserted in the quotation indicate an automatic leap in Veiller's mind, a leap made by virtually all reformers of his day. Any single-room life automatically meant the worst possible case, which Veiller castigated as the "common lodging house" filled with "homeless men and women." Writing to his audience of legislators, lawyers, and lobbyists, Veiller was careful to note in another section that activists could not legally label hotels and lodging houses as nuisances, since common law and the jurisprudence of the time recognized only sanitary or health problems as worthy of legal exclusion. Even the cheapest lodging house, when new, did not present the health problems that tuberculosis officers found in older ones. But Veiller clearly implied that hotel buildings were public nuisances. The wholesale adoption of Veiller's building codes in many states, including California, proved that reformers elsewhere agreed.

To someone watching the building of the city up to 1920, all the antihotel work of the Victorian and Progressive Era reformers might have seemed for naught. They had enunciated antihotel opinions but typically had not stopped new residential hotel construction or operation. Reformers had accomplished changes of rhetoric more than changes of action. In fact, the early 1920s were a boom period for hotel building and hotel living of most sorts. However, while the laws were not yet adequate to eradicate single-room homes, American law had begun to recognize residential hotels as a nuisance. The foundation of professional and public opinion encouraged by the Progressive Era reformers would serve to exclude the option of hotel homes in urban culture as developers rebuilt the old city of pre-World War I and expanded the new automobile suburbs. Housing action of the future would ensure new homes that were uniformly separate, sanitary, and (most of all) centrally approved.