Stratification of Owners

A hotel investor's available capital naturally affected the size of his or her building and the duration of ownership. Small-scale business people and professionals tended to buy small hotels on the fringes of downtown as income property. They held on to their properties for long periods. Well-connected and large-scale capitalists secured the big downtown hotels that often had faster turnover in ownership and were thus more liquid investments. Owner-managers like Smith and Rolkin fit into a pattern between these two groups.

The cheap lodging houses of San Francisco attracted more large-scale investment than did rooming houses, but the investors were rarely people of high social status. Judging from a San Francisco sample of hotel ownership from 1910 to 1980, over half of the lodging house rooms in the city were built or held by people who were of relatively low social standing but who often had amassed enough wealth to own citywide strings of lodging house properties.[3] The strings usually included the largest and most profitable cheap hotels. The owners of

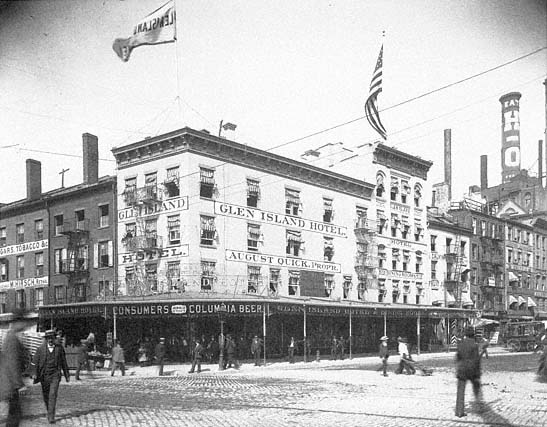

Figure 6.1

Prominent proprietor's sign on a nineteenth-century hotel. This waterfront hotel, probably of the

rooming house rank, was photographed on West Street in New York City about 1890.

cheap lodging houses typically ran hotels as their primary business; unlike wealthy investors, they were not merely investing surplus income.

At the time of the earthquake in 1906, the fairly young Edward Rolkin already owned twenty small hotels. His hotel buildings were not well insured (they may have been so dilapidated that they were uninsurable), and his total disaster insurance settlement was only $2,500. Rolkin still owned twenty parcels of prime South of Market land, however, and with these as collateral he continued to build and buy hotels throughout the neighborhood. As in the prefire years, he and his wife lived in and actively managed the hotels, moving every few years as he bought a new one (fig. 6.2). From 1906 to the 1920s, Rolkin acquired several new choice properties, including four of the city's largest workers' hotels and some of the most notorious as well. From 1906 to 1911, he worked to assemble the four South of Market lots he needed to build his new 375-room Reno Hotel, named after the first hotel he had managed in the city. As a result of such entrepreneurship, Rolkin was a

Figure 6.2

A four-alarm fire at one of Edward Rolkin's hotels,

The Denver House, in 1952. Located on Third

Street at Tehama in San Francisco, the hotel

had 180 lodging house rooms.

millionaire by the 1930s.[4] He and his wife, Arline, seem to have lived in their hotels until about 1935, when (in old age) they removed to a comfortable but merely middle-income district of town (fig. 6.3). A similar string of cheap San Francisco lodging houses was owned in the 1920s by Jules, Louis, and Joseph Marty. They held at least nine workers' hotels in Chinatown and the South of Market. In their private lives, the Marty brothers and their wives and children lived in the relatively ordinary Mission district, an area where immigrants emerged into the lower end of the middle and upper class.[5]

Not all inexpensive hotels had immigrant owners. In San Francisco, especially for a small new lodging or rooming house on the edge of downtown, the archetypical builder and owner was a doctor or the proprietor of a small downtown retail business. In over half the sample cases, the doctor or business owner lived in Pacific Heights, a well-known and expensive enclave of the city's middle and upper class. The Portland Hotel, a wretched wooden cubicle hostelry that the city tried

Figure 6.3

The modest house of a millionaire skid row landlord. Edward Rolkin's house

at 1275 Stanyon, San Francisco, 1992. Rolkin and his wife lived in their various

hotels until late in life. This is the only house they ever bought.

to condemn in 1916, belonged to a brass works manager who lived in the suburb of Berkeley. The owner was probably holding the hotel as a possible expansion site for his machine shop. He sold the hotel to an ophthalmologist from Pacific Heights who owned it for a much longer time. On a lot on Sixth Street, an optician built the Delta Hotel, a downtown rooming house, and the family held the property from 1906 to 1959. The Sierra House near Columbus and Broadway belonged to a family of wholesale grocers from 1909 to 1944; the first generation of the family lived in Pacific Heights, and their children watched the property from Piedmont, an exclusive suburb fifteen miles away.[6]

In another common pattern, a real estate developer would assemble a parcel of land, build a hotel, and then sell it to a lawyer, doctor, or other financially secure person. Two to four such investors often joined in a partnership to buy a building. Like individual owners, the original partnerships of the early 1900s seem to have held hotels as fairly long-term investments. This rule held until the turn-of-the-century investing generation died—in San Francisco, typically until the 1940s or early 1950s.

The Pacific Heights style of individual ownership or two- or three-person partnerships held particularly true for rooming houses. Such middle and upper class owners, detached from the direct management of their hotel properties, seem to have made up the bulk of the owners for the large areas considered "zones of transition" during the 1930s.

Yet the original owners rarely saw the so-called transition take place. They typically willed the hotel to sons or daughters, who also held on to it as an investment. Until the mid-1960s, these heirs held the property for its immediate income, tax write-offs, and speculative value. The property value may have been relatively low, but as part of the site for tomorrow's office tower or expanded factory, the rooming house land could quadruple in value.[7] Therefore, in these zones of transition especially, neither the original nor the inheriting ownership generations were primarily building a civilization without homes. Rather, they were holding land in order to build something else. The civilization without homes was a side effect. In contrast, when Rolkin built a hotel, he chose its location, design, and management with the intention that it be a permanent cheap lodging house.

A real estate market below the level of small new hotels was composed of small used hotels. As with other downtown property, the price of an older hotel relied more on the value of its land than that of the structure. In the 1920s, one wooden rooming house of thirty-nine rooms southwest of San Francisco's downtown sold for as little as $14,000—approximately the price of a duplex in an outlying streetcar district of the city.[8]

Generally, only the already wealthy—those with substantial inherited capital or a name that invoked the significant trust of lenders—could count on the loans required to build or buy large polite hotels in the heart of downtown. They usually did so as one of several investment vehicles. Midpriced hotels were built by people of substantial means—not the highest elite but often people who already had other good properties in the city. For a midpriced hotel of one hundred rooms in San Francisco, the owners would very often be a partnership of two such families, one of whom had inherited a choice downtown lot. Sarah Pettigrew (whose deceased husband had been an officer in a wholesale grocery firm) and Mary E. Callahan built the substantial Hotel Victoria in 1907–08, creating the plot by assembling two adjacent downtown lots (fig. 6.4). Sarah's brother managed the hotel for a time.[9] Edward Beck built the 106-room Colonial Hotel in 1912, directly next door to the family's Beck Apartments. Joseph Brandenstein, an early resident of the city and a wealthy tobacco importer turned investor, built the Hotel York on one of his larger properties. He himself lived in an appropri-

Figure 6.4

The Hotel Victoria on Bush Street,

San Francisco, in December 1934.

ately large Victorian mansion in Pacific Heights, near the holders of the Levi-Strauss company fortune.[10]

Hotel properties in the core of downtown tended to turn over more frequently than rooming and lodging houses in the periphery. The Hotel Victoria's original owners, Pettigrew and Callahan, sold to another woman in just two years. Major changes of ownership occurred again in 1917, 1921, and 1934.[11] The palace-rank Hotel Bellevue, when its founding family sold it in 1916, saw two rapid turnovers until a resident owner and manager bought it in 1923.[12]

At the very top of the hotel property market were the builders of palace hotels, usually people competing to lead the city's finances and high society. Moneyed families not in the opera- or museum-endowing circle could erect palatial new hotels to gain or control social leadership. In San Francisco, trustees of the Charles Crocker estate, which was based on the notoriously unpopular profits of the Southern Pacific Railroad, decided to compete with the stodgy Palace Hotel by building the St. Francis Hotel. (The site of the Crocker mansion itself became the site of the Episcopal cathedral). Not long afterward, on the Nob Hill site that Comstock silver king James Fair had bought for his mansion, his daughter built the Fairmont Hotel. Terraces cascaded down

the hill from the Fairmont; its opulence, hilltop views, and relatively quiet location made it a residential favorite for wealthy tenants and a monument to the Fair family.[13]

Grand hotels did more than open a route for nouveaux riches to memorialize a fortune. On occasion, grand hotels also allowed bright, enterprising people to wedge themselves into the highest strata of society, as shown by the career of George D. Smith and his family. Smith was an engineer born and educated in Berkeley. He worked professionally at his father's mines and also forged his own Nevada political connections and mining profits. His wife, Eleanor Hart, was from a solid Central Valley business family with impeccable pioneer California credentials. In 1922, when Smith was thirty-three years old, he and his wife moved to San Francisco to join George's sister in leasing and personally operating two hotels. Having undergone this self-paced hotel management training for a year, Smith gave up his other property interests to build the city's elegant Canterbury Hotel. Four years later, with his sister remaining as the manager at the Canterbury, he bought the Nob Hill site of the razed Mark Hopkins mansion. (Hopkins had been another of the Southern Pacific Railroad owners.) Smith then constructed the eighteen-story Mark Hopkins Hotel, instantly one of the palace hotel landmarks on the West Coast (fig. 6.5).[14]

Smith believed in downtown living, and he built and managed for it. In the plans for both the Canterbury and the Mark Hopkins he included larger-than-usual rooms with larger-than-usual closets, which adapted very well to the needs of permanent residents. At the Mark Hopkins, he called for a number of self-contained residential suites with refrigerators and electric kitchens. Permanent residents had claimed half the rooms of the Mark Hopkins before it opened, and its residential clientele remained substantial through the 1950s. In 1929, Smith gained controlling interest in the Fairmont Hotel across the street; for a time he managed both hotels, remodeling aggressively. Smith and his wife continued to live in the Mark Hopkins until 1962, and they raised their family there. Smith's business acumen and buoyant personality explain the success of his profitable hotel career as much as his remarkable access to loans. His reputation remains that of a model hotel keeper.[15]

Smith's personal involvement in his hotels was more typical of the nineteenth- than of the twentieth-century hotel owner; nonetheless, his

Figure 6.5

Recent photograph of the Mark Hopkins Hotel, opened in 1927 on the site

of the Southern Pacific Railroad magnate's mansion. The corner of the

Fairmont Hotel can be seen to the left.

capital management matched the modern owner. Except for the Mark Hopkins, he sold all of his luxury hotels after only a few years. Smith and Rolkin were both leaders in the hotel business, but because they combined ownership and management, they were exceptions. More typical owners relied on hired managerial talent.