Owners and Managers

No architect or real estate agent wanted to admit it, but the success of a hotel relied more on management than either ownership or architecture. Well into the twentieth century, hotel advertisements and facades listed the manager prominently (fig. 6.1). In the nineteenth century, people held hotel keepers to be consummate business operators. When Americans doubted someone's cleverness they would say, "He's a fine man, but he can't keep a hotel."[2] Americans were also not surprised when a woman successfully managed a hotel, as women were assumed to possess myriad household management skills.

Most owners had to compete at luring good managers to their hotel. Some owners became their own hotel managers. The San Francisco entrepreneurs Edward Rolkin and George D. Smith epitomize two common types of the combination owner-manager. Both made fortunes from hotel keeping. However, Rolkin was a Polish immigrant, and Smith was a well-born Californian. They did not belong to the same clubs and probably rarely met. Their different social class positions limited them to reasonably specific patterns. However, as leading hotel keepers who were both owners and managers they set the pace for their respective contemporaries.

Stratification of Owners

A hotel investor's available capital naturally affected the size of his or her building and the duration of ownership. Small-scale business people and professionals tended to buy small hotels on the fringes of downtown as income property. They held on to their properties for long periods. Well-connected and large-scale capitalists secured the big downtown hotels that often had faster turnover in ownership and were thus more liquid investments. Owner-managers like Smith and Rolkin fit into a pattern between these two groups.

The cheap lodging houses of San Francisco attracted more large-scale investment than did rooming houses, but the investors were rarely people of high social status. Judging from a San Francisco sample of hotel ownership from 1910 to 1980, over half of the lodging house rooms in the city were built or held by people who were of relatively low social standing but who often had amassed enough wealth to own citywide strings of lodging house properties.[3] The strings usually included the largest and most profitable cheap hotels. The owners of

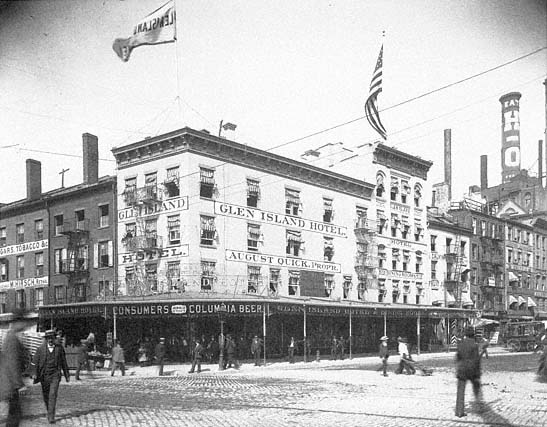

Figure 6.1

Prominent proprietor's sign on a nineteenth-century hotel. This waterfront hotel, probably of the

rooming house rank, was photographed on West Street in New York City about 1890.

cheap lodging houses typically ran hotels as their primary business; unlike wealthy investors, they were not merely investing surplus income.

At the time of the earthquake in 1906, the fairly young Edward Rolkin already owned twenty small hotels. His hotel buildings were not well insured (they may have been so dilapidated that they were uninsurable), and his total disaster insurance settlement was only $2,500. Rolkin still owned twenty parcels of prime South of Market land, however, and with these as collateral he continued to build and buy hotels throughout the neighborhood. As in the prefire years, he and his wife lived in and actively managed the hotels, moving every few years as he bought a new one (fig. 6.2). From 1906 to the 1920s, Rolkin acquired several new choice properties, including four of the city's largest workers' hotels and some of the most notorious as well. From 1906 to 1911, he worked to assemble the four South of Market lots he needed to build his new 375-room Reno Hotel, named after the first hotel he had managed in the city. As a result of such entrepreneurship, Rolkin was a

Figure 6.2

A four-alarm fire at one of Edward Rolkin's hotels,

The Denver House, in 1952. Located on Third

Street at Tehama in San Francisco, the hotel

had 180 lodging house rooms.

millionaire by the 1930s.[4] He and his wife, Arline, seem to have lived in their hotels until about 1935, when (in old age) they removed to a comfortable but merely middle-income district of town (fig. 6.3). A similar string of cheap San Francisco lodging houses was owned in the 1920s by Jules, Louis, and Joseph Marty. They held at least nine workers' hotels in Chinatown and the South of Market. In their private lives, the Marty brothers and their wives and children lived in the relatively ordinary Mission district, an area where immigrants emerged into the lower end of the middle and upper class.[5]

Not all inexpensive hotels had immigrant owners. In San Francisco, especially for a small new lodging or rooming house on the edge of downtown, the archetypical builder and owner was a doctor or the proprietor of a small downtown retail business. In over half the sample cases, the doctor or business owner lived in Pacific Heights, a well-known and expensive enclave of the city's middle and upper class. The Portland Hotel, a wretched wooden cubicle hostelry that the city tried

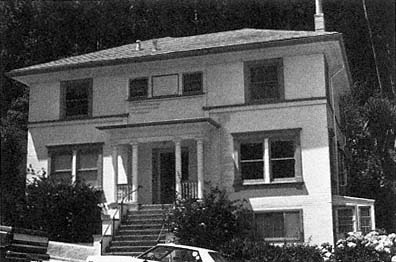

Figure 6.3

The modest house of a millionaire skid row landlord. Edward Rolkin's house

at 1275 Stanyon, San Francisco, 1992. Rolkin and his wife lived in their various

hotels until late in life. This is the only house they ever bought.

to condemn in 1916, belonged to a brass works manager who lived in the suburb of Berkeley. The owner was probably holding the hotel as a possible expansion site for his machine shop. He sold the hotel to an ophthalmologist from Pacific Heights who owned it for a much longer time. On a lot on Sixth Street, an optician built the Delta Hotel, a downtown rooming house, and the family held the property from 1906 to 1959. The Sierra House near Columbus and Broadway belonged to a family of wholesale grocers from 1909 to 1944; the first generation of the family lived in Pacific Heights, and their children watched the property from Piedmont, an exclusive suburb fifteen miles away.[6]

In another common pattern, a real estate developer would assemble a parcel of land, build a hotel, and then sell it to a lawyer, doctor, or other financially secure person. Two to four such investors often joined in a partnership to buy a building. Like individual owners, the original partnerships of the early 1900s seem to have held hotels as fairly long-term investments. This rule held until the turn-of-the-century investing generation died—in San Francisco, typically until the 1940s or early 1950s.

The Pacific Heights style of individual ownership or two- or three-person partnerships held particularly true for rooming houses. Such middle and upper class owners, detached from the direct management of their hotel properties, seem to have made up the bulk of the owners for the large areas considered "zones of transition" during the 1930s.

Yet the original owners rarely saw the so-called transition take place. They typically willed the hotel to sons or daughters, who also held on to it as an investment. Until the mid-1960s, these heirs held the property for its immediate income, tax write-offs, and speculative value. The property value may have been relatively low, but as part of the site for tomorrow's office tower or expanded factory, the rooming house land could quadruple in value.[7] Therefore, in these zones of transition especially, neither the original nor the inheriting ownership generations were primarily building a civilization without homes. Rather, they were holding land in order to build something else. The civilization without homes was a side effect. In contrast, when Rolkin built a hotel, he chose its location, design, and management with the intention that it be a permanent cheap lodging house.

A real estate market below the level of small new hotels was composed of small used hotels. As with other downtown property, the price of an older hotel relied more on the value of its land than that of the structure. In the 1920s, one wooden rooming house of thirty-nine rooms southwest of San Francisco's downtown sold for as little as $14,000—approximately the price of a duplex in an outlying streetcar district of the city.[8]

Generally, only the already wealthy—those with substantial inherited capital or a name that invoked the significant trust of lenders—could count on the loans required to build or buy large polite hotels in the heart of downtown. They usually did so as one of several investment vehicles. Midpriced hotels were built by people of substantial means—not the highest elite but often people who already had other good properties in the city. For a midpriced hotel of one hundred rooms in San Francisco, the owners would very often be a partnership of two such families, one of whom had inherited a choice downtown lot. Sarah Pettigrew (whose deceased husband had been an officer in a wholesale grocery firm) and Mary E. Callahan built the substantial Hotel Victoria in 1907–08, creating the plot by assembling two adjacent downtown lots (fig. 6.4). Sarah's brother managed the hotel for a time.[9] Edward Beck built the 106-room Colonial Hotel in 1912, directly next door to the family's Beck Apartments. Joseph Brandenstein, an early resident of the city and a wealthy tobacco importer turned investor, built the Hotel York on one of his larger properties. He himself lived in an appropri-

Figure 6.4

The Hotel Victoria on Bush Street,

San Francisco, in December 1934.

ately large Victorian mansion in Pacific Heights, near the holders of the Levi-Strauss company fortune.[10]

Hotel properties in the core of downtown tended to turn over more frequently than rooming and lodging houses in the periphery. The Hotel Victoria's original owners, Pettigrew and Callahan, sold to another woman in just two years. Major changes of ownership occurred again in 1917, 1921, and 1934.[11] The palace-rank Hotel Bellevue, when its founding family sold it in 1916, saw two rapid turnovers until a resident owner and manager bought it in 1923.[12]

At the very top of the hotel property market were the builders of palace hotels, usually people competing to lead the city's finances and high society. Moneyed families not in the opera- or museum-endowing circle could erect palatial new hotels to gain or control social leadership. In San Francisco, trustees of the Charles Crocker estate, which was based on the notoriously unpopular profits of the Southern Pacific Railroad, decided to compete with the stodgy Palace Hotel by building the St. Francis Hotel. (The site of the Crocker mansion itself became the site of the Episcopal cathedral). Not long afterward, on the Nob Hill site that Comstock silver king James Fair had bought for his mansion, his daughter built the Fairmont Hotel. Terraces cascaded down

the hill from the Fairmont; its opulence, hilltop views, and relatively quiet location made it a residential favorite for wealthy tenants and a monument to the Fair family.[13]

Grand hotels did more than open a route for nouveaux riches to memorialize a fortune. On occasion, grand hotels also allowed bright, enterprising people to wedge themselves into the highest strata of society, as shown by the career of George D. Smith and his family. Smith was an engineer born and educated in Berkeley. He worked professionally at his father's mines and also forged his own Nevada political connections and mining profits. His wife, Eleanor Hart, was from a solid Central Valley business family with impeccable pioneer California credentials. In 1922, when Smith was thirty-three years old, he and his wife moved to San Francisco to join George's sister in leasing and personally operating two hotels. Having undergone this self-paced hotel management training for a year, Smith gave up his other property interests to build the city's elegant Canterbury Hotel. Four years later, with his sister remaining as the manager at the Canterbury, he bought the Nob Hill site of the razed Mark Hopkins mansion. (Hopkins had been another of the Southern Pacific Railroad owners.) Smith then constructed the eighteen-story Mark Hopkins Hotel, instantly one of the palace hotel landmarks on the West Coast (fig. 6.5).[14]

Smith believed in downtown living, and he built and managed for it. In the plans for both the Canterbury and the Mark Hopkins he included larger-than-usual rooms with larger-than-usual closets, which adapted very well to the needs of permanent residents. At the Mark Hopkins, he called for a number of self-contained residential suites with refrigerators and electric kitchens. Permanent residents had claimed half the rooms of the Mark Hopkins before it opened, and its residential clientele remained substantial through the 1950s. In 1929, Smith gained controlling interest in the Fairmont Hotel across the street; for a time he managed both hotels, remodeling aggressively. Smith and his wife continued to live in the Mark Hopkins until 1962, and they raised their family there. Smith's business acumen and buoyant personality explain the success of his profitable hotel career as much as his remarkable access to loans. His reputation remains that of a model hotel keeper.[15]

Smith's personal involvement in his hotels was more typical of the nineteenth- than of the twentieth-century hotel owner; nonetheless, his

Figure 6.5

Recent photograph of the Mark Hopkins Hotel, opened in 1927 on the site

of the Southern Pacific Railroad magnate's mansion. The corner of the

Fairmont Hotel can be seen to the left.

capital management matched the modern owner. Except for the Mark Hopkins, he sold all of his luxury hotels after only a few years. Smith and Rolkin were both leaders in the hotel business, but because they combined ownership and management, they were exceptions. More typical owners relied on hired managerial talent.

Managers

As many as nine out of ten owners of large hotels did not personally manage their property. To the owners, the hotel was often strictly a real estate investment, no more meaningful to them than a speculative office building or warehouse. They typically leased the building to a manager for one to ten years. The contract details varied: a high fixed fee per year gave the owners a guaranteed income and left the remaining profits to the managers; leases at lower annual rates gave

the owners a percentage of the gross receipts. Either method repaid construction loans quickly and gave the owner relatively worry-free income as long as hotel business was good at that location. At the turn of the century, owners proudly announced the cost of the lease (along with the cost of the building if it was new) in the local newspapers. In 1909, for instance, the Haas Realty Company began a $95,000 hotel just two blocks from San Francisco's Union Square. While construction was under way, they sealed a lease with the first manager, who over ten years was to pay the company $177,600 to operate the 108-room hotel and its ground-floor German grill.[16]

Hotel furniture often belonged to the manager, not the building owner; change of management included the sale of interior furnishings. In the 1890s, new furniture and fittings of an elegant family hotel might cost $400 a room, while a few blocks away, the manager of a cheap rooming house might pay only $50 a room. In the midpriced hotel range, the fittings, furniture, and dining room equipment could cost as much as 60 percent of the cost of the building.[17]

Published guides existed to help managers decipher the commercial metabolism of the United States, but most hotel owners and managers relied as much on hunches and personal experience.[18] While bargaining on a lease for a hotel with a bar and dining room, the astute hotel manager counted on the bar for positive cash flow. Dining rooms, other food service, and hotel entertainment offered virtually no chance for profit; at best, they broke even. The bar, however, generated a hefty share of the hotel's income and often paid rent, heat, and light for the whole building. Similarly, store rentals on the ground floor often carried the hotel's interest charges and some of the mortgage principal.[19]

Managers needed leadership ability, sound judgment, and good legal counsel for the daily demands of coordinating a complicated staff. At a polite hotel, that meant a 24-hour supply of maids, bellboys, elevator operators, kitchen assistants, janitors, and plumbers, along with a sizable number of clerks and midlevel supervisors. Much of the hotel management literature chronicles labor strife and methods to reduce it. To keep good workers nearby, builders of large hotels often constructed rooms in the attic or at the back of the hotel as living quarters for a share of the employees. Owners of gargantuan hotels like San Francisco's Palace built neighboring rooming houses with one hundred rooms or more, largely rented to their staff. Rooming houses and cheap lodg-

ing houses required a smaller but equally essential supply of maids and repair people.

Besides assuring the necessary staff support, the motive of a hotel manager was filling as many rooms as possible every night. In 1930, a hotel management report put it this way:

Hotel business differs from the general run of manufacturing in the perishability of its product. Time . . . is the major item that a hotel man has for sale. Every unsold room in his house every night represents an irretrievable loss, for that night will never return.[20]

To attract and keep permanent residents, managers of all types of hotels had to give appropriate attention to their clients, and the manager-tenant relationship was often very personal. Palace hotel managers personally assured wealthy clients that they would have the same suite each year and welcomed them with flowers and a personal note in their room when they arrived. Other managers chatted with tenants daily, or if they were managing a rooming house with elderly residents they helped them read and write letters, do their shopping, make doctor's appointments, or arrange ambulance service. At cheap lodging houses, good clerks made a point of greeting tenants by name and playing host to the group in the lobby to give them a sense of belonging and being at home (fig. 6.6). During strikes, rooming house keepers won loyalty from tenants by extending credit until the strike was over.[21]

When Prohibition cut off bar receipts, even more of the manager's attentions went to maintaining high room occupancy. By the 1920s, in a larger hotel a room occupancy rate of 70 percent was usually needed to break even. Seasonal changes in occupancy were another cash flow reality. When transient guest numbers were low in most palace and midpriced hotels, managers often took in more permanent guests. Monthly room rates were always substantially lower than the prorated daily or weekly rates—often only a fraction of the daily rate—but nonetheless managers could count on that residential income to cover fixed operating expenses.[22]

On similar sites, hotel buildings were known as potentially higher income properties than apartment buildings. Hotels made less money than apartments during business troughs but much more money in busy seasons. Apartments usually offered relatively steady cash flow year-round.[23] After 1920, real estate investors with a small amount of

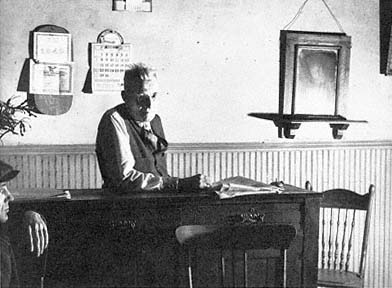

Figure 6.6

Desk clerk in a cheap lodging house in Dubuque, Iowa, photographed in 1940.

Note the casual arrangement of chairs.

capital, or those who wanted to rely on a housing investment as a significant part of their day-to-day income (for retirement income, perhaps), seem to have preferred apartments over hotels.

In the 1890s, the majority of the midpriced family hotels in San Francisco were run by women managers, and women managers were also reasonably common in other types of hotels. A California journalist explained in 1892 that the woman in business may have been questioned in some quarters, but "as a manager of large family hotels and rooming-houses, she is an eminent success" (fig. 6.7).[24] In 1900, up to 95 percent of American rooming house keepers were women. In most cities, about half of these rooming house operators were widows; the married rooming house operators typically had husbands who were wage laborers. Income from small rooming houses was more touch and go than at larger hotels. Unless the woman owned the building, its revenue was not substantial. The small rooming house operators leased their building by the year and bought the furniture on time payments. Typically, both the lease and the furniture purchase were arranged through a real estate broker who specialized in such deals and either owned the buildings outright or managed them for investors.[25] In spite of the meager income available, becoming a rooming house keeper was one of the occupations most available to mature self-supporting women before World War II. Older waitresses, for instance, commonly dreamed of leasing a rooming house instead of slinging hash in a cheap

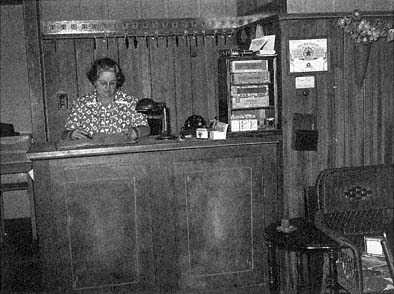

Figure 6.7

Desk clerk in a small rooming house in San Augustine, Texas, 1939.

Even in the nineteenth century, women were commonly hotel keepers.

restaurant. Yet many women went broke in their first year, not realizing the seasonal shifts or other expenses. They lost the money they had paid on the furniture and had to forfeit everything to the rooming house brokers. The brokers then easily found another recently widowed woman willing to invest her small nest egg on a rooming house venture. Rooming house real estate brokerages were so shady that some hotel brokers, to appear reputable, overtly advertised "strict conformance to upright business principles."[26]

Cycles of Investment and Construction

Particular years were noted for surges in all types of hotel investment. San Francisco directories record how quickly the number of hotels changed in response to potential business (fig. 6.8). Peaks of hotel listings coincided with surges in the local and national business climate, particularly in response to increased industrial and office employment, wars or other widespread investment stimuli, and surges in tourist travel. Troughs in the number of hotels corresponded to employment and travel slumps.[27]

Mercantile and industrial expansion—and the ensuing population movement—triggered good business for hotels of all types. The first major peak in San Francisco's hotel listings, from the mid-1890s to 1905, followed production surges for the Spanish-American War, discovery of gold in the Klondike, and increasing Philippine and Pacific

Figure 6.8

Graph showing total number of hotel listings in the San Francisco

directories from 1870 to 1970.

Basin trade. It also coincided with the stimulation of Pacific Coast business due to the promise of the new Panama Canal trade and the rapid growth of population and markets in the American West.[28] San Francisco's great earthquake and fire of 1906 only briefly interrupted hotel business. In the aftermath, a great many hotels were built for workers and for households displaced by the destruction. No drastic land-use changes occurred in the rebuilding; the fire merely hastened and highlighted gradual developments already under way in real estate investments for the center section of the city.[29] At the scale of individual lots, the average hotel business before the fire had about 30 to 60 rooms; after the fire, each business listed in the directory was more likely to be on a lot twice as large and to have from 40 to 100 rooms.[30] Thus, although the number of individual hotels in San Francisco peaked in 1906 (the year of the fire), the peak in hotel rooms came after World War I.

Hotel keeper E. M. Statler called World War I "the best five years American hotels ever had." (He could not have imagined the boom of

World War II.) Wartime meant expanded employment. New hotels of all ranks were built or converted for war demands, and each wartime boom stretched all existing hotels to their maximum potential—and sometimes beyond. War industry workers packed into lodging houses and rooming houses while the better hotels did thriving business with war-material brokers, production engineers, government officials, and military officers. The only single-room housing operations that languished in World War I were the free municipal lodging houses and other flophouse adjuncts in some cities, which were made less necessary by high wartime employment. The Chicago Municipal Lodging House closed entirely in 1918 –19 because of lack of applicants.[31]

After World War I, generally, only the directors of philanthropic rooming houses (such as new YWCAs) and owners of midpriced and palace hotels added to the stock of hotel rooms. Again, the San Francisco case is typical.[32] From 1918 to 1921, manufacturing employment decreased in San Francisco industries by 4,000 employees, down almost 10 percent; by 1925, it had dropped by another 4,000. Hence, private downtown housing investors in San Francisco built neither lodging houses nor rooming houses after World War I. A share of this downtown decline also resulted from mechanization in the work place and the steady relocation of industries to the edge of the city.[33]

Within these broad swings in hotel business, several market processes operated. Perhaps the least rational were those behind the building of palace hotels and some midpriced hotels. Beginning in the 1820s, each generation of city business leaders felt compelled to adorn their town with a state-of-the-art hotel—usually larger and more lavish than strictly necessary—to assure their city's regional or national stature. In the 1920s, palace hotels began to vie even with office skyscrapers as the largest buildings in major cities. Not all of this was sheer boosterism. For two centuries Americans have responded positively to size in hotels as they have responded to size in other commercial attractions. The biggest hotel in town also commanded monopoly rates and the largest conventions.

In the battle between city boosters in different towns and between different expensive hotels, design and fashion as well as size figured prominently. As the competition between a city's better hotels increased, the owners and managers came to rely more on the tools of high-style design, attention-catching interior decorating, spectacular

cooking, and innovative engineering. In every generation, owners and their architects informally settled on a prevailing facade style for hotels; for interiors, managers and their designers changed the reigning style almost twice as often. Thus, to remain in fashion, hotel managers had to search for better chefs constantly, redecorate about every ten years, and significantly remodel or add new wings at least once every twenty to twenty-five years. Watching the constant competition between grand hotels, Sinclair Lewis observed that "next to love, nothing loses its rank so quickly as a leading hotel."[34]

When hotel owners demanded ever-larger hotels to pay for evermore-expensive downtown land, architects responded with new types of floor plans. On larger sites, designers provided wings of rooms separated by larger and wider light wells. In an "E" or "C" shape, the floor plans yielded more rooms with two- and three-way exposure for better cross-ventilation and light. Engineering also set new hotel fashions. For every passing decade's conspicuous innovative gadget—calling-card elevator, exuberant lighting display, ice water tap, or built-in radio—managers installed many more machines to reduce labor costs. By 1900, the design and outfitting of hotels had become complex enough so that a few architecture and engineering firms specialized in hotel design and did a significant share of the nation's large hotel business.[35]

The use of elevators particularly revolutionized hotel life. With elevator access, the rooms on upper floors (once the cheapest rooms) became the most expensive. By the 1920s, tower views from high palace hotel rooms had become another aspect of hotel living that expensive private houses could not outdo.[36] In San Francisco, it was George Smith who best captured the skyscraper view. In 1939, to compete with new post-Prohibition bars and nightclubs opening throughout the city, he opened the Top of the Mark at the remodeled crown of his hotel, where a penthouse apartment had been. Smith also hired the talented architectural office of Timothy Pfleuger to give the Top of the Mark the Manhattan sheen of Art Deco style.[37]

Managers who chose not to compete in the size, chef, or gadget game typically dropped their hotels to a lower rank of clientele by cutting the amount of service, closing lavish dining rooms, or changing from American plan to European plan rates. With such cuts in service, a palace hotel could be profitably run as a midpriced hotel. In the late 1920s, so many boosters had built so many good hotels that in most cities

Figure 6.9

The Gateway District of Minneapolis, photographed in 1939. Through the filtering of clients, this Victorian

midpriced hotel district had shifted to cheap lodging house status.

there were price wars and substantially lower transient occupancy rates. Simultaneously, motels and auto courts were beginning to cut into the family travel market. Such overbuilding stimulated more permanent occupancy to fill the rooms. Managers lured tenants with ads proclaiming, "Occupancy from October! Lease from January! Fifteen months for the rent of twelve."[38]

For all types of hotels, shifts of social cachet, demographic changes in surrounding neighborhoods, or losses in nearby employment triggered the process of filtering: first, former permanent guests gradually filtered out to newer, more comfortable, or better-located quarters; second, to keep occupancy levels high, managers at the older hotels lowered their prices, allowing less affluent tenants to filter in; finally, the remaining earlier tenants left, feeling that their social standing, comfort, or safety was in jeopardy. In any American city, it was not unusual in the 1920s to see handsomely designed and fashionable family hotels of the 1880s that had devolved to inexpensive rooming houses for unskilled or unemployed workers.[39] Cheaper hotels, too, filtered to lower-income tenants (fig. 6.9). In the core of San Francisco's South of Market

district, the managers of several hotels built in 1906 had by 1919 discontinued polite hotel services and given up the term "hotel"; they simply ran their establishments as more casual rooming houses or lodging houses. On one block alone, three out of four hotels had seen this conversion.[40]

To maintain high profits in spite of lower rents, owners of rooming or lodging houses could reduce repair budgets and employ only minimally skilled managers or staff. What observers called the "visual decay" of rooming house districts was usually the evidence of inept or uncaring management and the literal erosion of architectural fabric: first cosmetic facade deterioration and then more serious structural dilapidation from decreased maintenance.[41]

Like the question of when to launch a new hotel business, the question of when to leave the hotel business was often prompted by the general urban metabolism and how it affected the neighborhood, hotel clientele, competition for the hotel site, and the cash flow of the property owner(s). If hotel managers could not sell their rooms to either tourists or permanent guests, and if shifting to cheaper clients did not work, owners often looked to office rentals or other nonhotel uses. At appropriate downtown locations hotel owners could rent rooms, whole floors, or the whole hotel as offices. Even in colonial times, hotels had mixed offices and sleeping rooms. In 1906, the Grand Central Hotel in San Francisco was consciously built to be either office or hotel space, and it saw both uses. The elegant Hotel Whitcomb served as San Francisco's city hall for a time after the great fire. About 1920, the owners of New York's Manhattan Hotel (even though it was the birthplace of the Manhattan cocktail) converted the twenty-four-year-old building to offices. Other hotel owners converted their properties to private hospitals (or vice versa). After 1945, however, demands for better electrical service, lighting, and air-conditioning made such office and hospital conversions less feasible.[42] When all else failed, a major old hotel's downtown site usually brought the owners a good price as the location for a new office tower. The most notable example of such conversion is the block that held the original Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, where the Empire State Building now stands. At times even perfectly profitable and viable hotels were torn down, revealing tensions that can exist between owners and managers. If the owners were convinced they could profit

more by closing the hotel and changing the building's use—and if the managers had lost their lease—no basis remained for the hotel to be in business, other than emotional appeals by the managers or clients.

Especially at the scale of the Empire State Building but also at more modest sites, the actions of individual owners and managers had a great influence on the surrounding blocks. Hotels collected large numbers of people who were a market for other retail services nearby. The hotel's staff also exerted a pressure for their own housing and for their retail needs. These influences, plus their voice in urban governance as landowners, gave hotel builders important roles in rebuilding downtown neighborhoods in a more organized way.