Chapter Six—

Building a Civilization without Homes

In 1919, the social historian arthur calhoun told his readers, "It would seem that our current capitalism is willing to try the experiment of a civilization without homes."[1] Calhoun saw hotel life as an experiment driven primarily by desires for commercial profits and real estate returns. Indeed, the people who built and managed hotels saw their investments and businesses as a natural and necessary part of the city economy. At the scale of individual buildings, hotel managers were key figures. They orchestrated staffs to manage life inside their hotels and did their best to make a personal gain. Building owners could also affect a wider sphere. When they individually improved their properties they often collectively changed an entire neighborhood as well. Hotel owners, like other downtown landowners, welcomed and fostered a more organized, more rational city of increasing architectural specialization and clearer social stratification. The individual actions of hotel owners—with those of other downtown landowners—combined to specialize whole districts and thereby revamped the nature of living downtown.

Owners and Managers

No architect or real estate agent wanted to admit it, but the success of a hotel relied more on management than either ownership or architecture. Well into the twentieth century, hotel advertisements and facades listed the manager prominently (fig. 6.1). In the nineteenth century, people held hotel keepers to be consummate business operators. When Americans doubted someone's cleverness they would say, "He's a fine man, but he can't keep a hotel."[2] Americans were also not surprised when a woman successfully managed a hotel, as women were assumed to possess myriad household management skills.

Most owners had to compete at luring good managers to their hotel. Some owners became their own hotel managers. The San Francisco entrepreneurs Edward Rolkin and George D. Smith epitomize two common types of the combination owner-manager. Both made fortunes from hotel keeping. However, Rolkin was a Polish immigrant, and Smith was a well-born Californian. They did not belong to the same clubs and probably rarely met. Their different social class positions limited them to reasonably specific patterns. However, as leading hotel keepers who were both owners and managers they set the pace for their respective contemporaries.

Stratification of Owners

A hotel investor's available capital naturally affected the size of his or her building and the duration of ownership. Small-scale business people and professionals tended to buy small hotels on the fringes of downtown as income property. They held on to their properties for long periods. Well-connected and large-scale capitalists secured the big downtown hotels that often had faster turnover in ownership and were thus more liquid investments. Owner-managers like Smith and Rolkin fit into a pattern between these two groups.

The cheap lodging houses of San Francisco attracted more large-scale investment than did rooming houses, but the investors were rarely people of high social status. Judging from a San Francisco sample of hotel ownership from 1910 to 1980, over half of the lodging house rooms in the city were built or held by people who were of relatively low social standing but who often had amassed enough wealth to own citywide strings of lodging house properties.[3] The strings usually included the largest and most profitable cheap hotels. The owners of

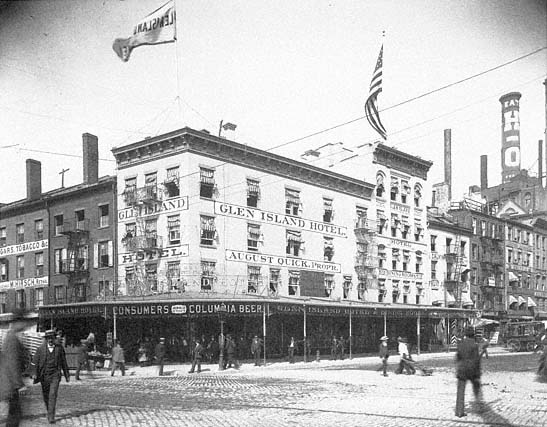

Figure 6.1

Prominent proprietor's sign on a nineteenth-century hotel. This waterfront hotel, probably of the

rooming house rank, was photographed on West Street in New York City about 1890.

cheap lodging houses typically ran hotels as their primary business; unlike wealthy investors, they were not merely investing surplus income.

At the time of the earthquake in 1906, the fairly young Edward Rolkin already owned twenty small hotels. His hotel buildings were not well insured (they may have been so dilapidated that they were uninsurable), and his total disaster insurance settlement was only $2,500. Rolkin still owned twenty parcels of prime South of Market land, however, and with these as collateral he continued to build and buy hotels throughout the neighborhood. As in the prefire years, he and his wife lived in and actively managed the hotels, moving every few years as he bought a new one (fig. 6.2). From 1906 to the 1920s, Rolkin acquired several new choice properties, including four of the city's largest workers' hotels and some of the most notorious as well. From 1906 to 1911, he worked to assemble the four South of Market lots he needed to build his new 375-room Reno Hotel, named after the first hotel he had managed in the city. As a result of such entrepreneurship, Rolkin was a

Figure 6.2

A four-alarm fire at one of Edward Rolkin's hotels,

The Denver House, in 1952. Located on Third

Street at Tehama in San Francisco, the hotel

had 180 lodging house rooms.

millionaire by the 1930s.[4] He and his wife, Arline, seem to have lived in their hotels until about 1935, when (in old age) they removed to a comfortable but merely middle-income district of town (fig. 6.3). A similar string of cheap San Francisco lodging houses was owned in the 1920s by Jules, Louis, and Joseph Marty. They held at least nine workers' hotels in Chinatown and the South of Market. In their private lives, the Marty brothers and their wives and children lived in the relatively ordinary Mission district, an area where immigrants emerged into the lower end of the middle and upper class.[5]

Not all inexpensive hotels had immigrant owners. In San Francisco, especially for a small new lodging or rooming house on the edge of downtown, the archetypical builder and owner was a doctor or the proprietor of a small downtown retail business. In over half the sample cases, the doctor or business owner lived in Pacific Heights, a well-known and expensive enclave of the city's middle and upper class. The Portland Hotel, a wretched wooden cubicle hostelry that the city tried

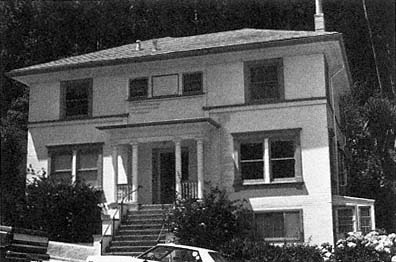

Figure 6.3

The modest house of a millionaire skid row landlord. Edward Rolkin's house

at 1275 Stanyon, San Francisco, 1992. Rolkin and his wife lived in their various

hotels until late in life. This is the only house they ever bought.

to condemn in 1916, belonged to a brass works manager who lived in the suburb of Berkeley. The owner was probably holding the hotel as a possible expansion site for his machine shop. He sold the hotel to an ophthalmologist from Pacific Heights who owned it for a much longer time. On a lot on Sixth Street, an optician built the Delta Hotel, a downtown rooming house, and the family held the property from 1906 to 1959. The Sierra House near Columbus and Broadway belonged to a family of wholesale grocers from 1909 to 1944; the first generation of the family lived in Pacific Heights, and their children watched the property from Piedmont, an exclusive suburb fifteen miles away.[6]

In another common pattern, a real estate developer would assemble a parcel of land, build a hotel, and then sell it to a lawyer, doctor, or other financially secure person. Two to four such investors often joined in a partnership to buy a building. Like individual owners, the original partnerships of the early 1900s seem to have held hotels as fairly long-term investments. This rule held until the turn-of-the-century investing generation died—in San Francisco, typically until the 1940s or early 1950s.

The Pacific Heights style of individual ownership or two- or three-person partnerships held particularly true for rooming houses. Such middle and upper class owners, detached from the direct management of their hotel properties, seem to have made up the bulk of the owners for the large areas considered "zones of transition" during the 1930s.

Yet the original owners rarely saw the so-called transition take place. They typically willed the hotel to sons or daughters, who also held on to it as an investment. Until the mid-1960s, these heirs held the property for its immediate income, tax write-offs, and speculative value. The property value may have been relatively low, but as part of the site for tomorrow's office tower or expanded factory, the rooming house land could quadruple in value.[7] Therefore, in these zones of transition especially, neither the original nor the inheriting ownership generations were primarily building a civilization without homes. Rather, they were holding land in order to build something else. The civilization without homes was a side effect. In contrast, when Rolkin built a hotel, he chose its location, design, and management with the intention that it be a permanent cheap lodging house.

A real estate market below the level of small new hotels was composed of small used hotels. As with other downtown property, the price of an older hotel relied more on the value of its land than that of the structure. In the 1920s, one wooden rooming house of thirty-nine rooms southwest of San Francisco's downtown sold for as little as $14,000—approximately the price of a duplex in an outlying streetcar district of the city.[8]

Generally, only the already wealthy—those with substantial inherited capital or a name that invoked the significant trust of lenders—could count on the loans required to build or buy large polite hotels in the heart of downtown. They usually did so as one of several investment vehicles. Midpriced hotels were built by people of substantial means—not the highest elite but often people who already had other good properties in the city. For a midpriced hotel of one hundred rooms in San Francisco, the owners would very often be a partnership of two such families, one of whom had inherited a choice downtown lot. Sarah Pettigrew (whose deceased husband had been an officer in a wholesale grocery firm) and Mary E. Callahan built the substantial Hotel Victoria in 1907–08, creating the plot by assembling two adjacent downtown lots (fig. 6.4). Sarah's brother managed the hotel for a time.[9] Edward Beck built the 106-room Colonial Hotel in 1912, directly next door to the family's Beck Apartments. Joseph Brandenstein, an early resident of the city and a wealthy tobacco importer turned investor, built the Hotel York on one of his larger properties. He himself lived in an appropri-

Figure 6.4

The Hotel Victoria on Bush Street,

San Francisco, in December 1934.

ately large Victorian mansion in Pacific Heights, near the holders of the Levi-Strauss company fortune.[10]

Hotel properties in the core of downtown tended to turn over more frequently than rooming and lodging houses in the periphery. The Hotel Victoria's original owners, Pettigrew and Callahan, sold to another woman in just two years. Major changes of ownership occurred again in 1917, 1921, and 1934.[11] The palace-rank Hotel Bellevue, when its founding family sold it in 1916, saw two rapid turnovers until a resident owner and manager bought it in 1923.[12]

At the very top of the hotel property market were the builders of palace hotels, usually people competing to lead the city's finances and high society. Moneyed families not in the opera- or museum-endowing circle could erect palatial new hotels to gain or control social leadership. In San Francisco, trustees of the Charles Crocker estate, which was based on the notoriously unpopular profits of the Southern Pacific Railroad, decided to compete with the stodgy Palace Hotel by building the St. Francis Hotel. (The site of the Crocker mansion itself became the site of the Episcopal cathedral). Not long afterward, on the Nob Hill site that Comstock silver king James Fair had bought for his mansion, his daughter built the Fairmont Hotel. Terraces cascaded down

the hill from the Fairmont; its opulence, hilltop views, and relatively quiet location made it a residential favorite for wealthy tenants and a monument to the Fair family.[13]

Grand hotels did more than open a route for nouveaux riches to memorialize a fortune. On occasion, grand hotels also allowed bright, enterprising people to wedge themselves into the highest strata of society, as shown by the career of George D. Smith and his family. Smith was an engineer born and educated in Berkeley. He worked professionally at his father's mines and also forged his own Nevada political connections and mining profits. His wife, Eleanor Hart, was from a solid Central Valley business family with impeccable pioneer California credentials. In 1922, when Smith was thirty-three years old, he and his wife moved to San Francisco to join George's sister in leasing and personally operating two hotels. Having undergone this self-paced hotel management training for a year, Smith gave up his other property interests to build the city's elegant Canterbury Hotel. Four years later, with his sister remaining as the manager at the Canterbury, he bought the Nob Hill site of the razed Mark Hopkins mansion. (Hopkins had been another of the Southern Pacific Railroad owners.) Smith then constructed the eighteen-story Mark Hopkins Hotel, instantly one of the palace hotel landmarks on the West Coast (fig. 6.5).[14]

Smith believed in downtown living, and he built and managed for it. In the plans for both the Canterbury and the Mark Hopkins he included larger-than-usual rooms with larger-than-usual closets, which adapted very well to the needs of permanent residents. At the Mark Hopkins, he called for a number of self-contained residential suites with refrigerators and electric kitchens. Permanent residents had claimed half the rooms of the Mark Hopkins before it opened, and its residential clientele remained substantial through the 1950s. In 1929, Smith gained controlling interest in the Fairmont Hotel across the street; for a time he managed both hotels, remodeling aggressively. Smith and his wife continued to live in the Mark Hopkins until 1962, and they raised their family there. Smith's business acumen and buoyant personality explain the success of his profitable hotel career as much as his remarkable access to loans. His reputation remains that of a model hotel keeper.[15]

Smith's personal involvement in his hotels was more typical of the nineteenth- than of the twentieth-century hotel owner; nonetheless, his

Figure 6.5

Recent photograph of the Mark Hopkins Hotel, opened in 1927 on the site

of the Southern Pacific Railroad magnate's mansion. The corner of the

Fairmont Hotel can be seen to the left.

capital management matched the modern owner. Except for the Mark Hopkins, he sold all of his luxury hotels after only a few years. Smith and Rolkin were both leaders in the hotel business, but because they combined ownership and management, they were exceptions. More typical owners relied on hired managerial talent.

Managers

As many as nine out of ten owners of large hotels did not personally manage their property. To the owners, the hotel was often strictly a real estate investment, no more meaningful to them than a speculative office building or warehouse. They typically leased the building to a manager for one to ten years. The contract details varied: a high fixed fee per year gave the owners a guaranteed income and left the remaining profits to the managers; leases at lower annual rates gave

the owners a percentage of the gross receipts. Either method repaid construction loans quickly and gave the owner relatively worry-free income as long as hotel business was good at that location. At the turn of the century, owners proudly announced the cost of the lease (along with the cost of the building if it was new) in the local newspapers. In 1909, for instance, the Haas Realty Company began a $95,000 hotel just two blocks from San Francisco's Union Square. While construction was under way, they sealed a lease with the first manager, who over ten years was to pay the company $177,600 to operate the 108-room hotel and its ground-floor German grill.[16]

Hotel furniture often belonged to the manager, not the building owner; change of management included the sale of interior furnishings. In the 1890s, new furniture and fittings of an elegant family hotel might cost $400 a room, while a few blocks away, the manager of a cheap rooming house might pay only $50 a room. In the midpriced hotel range, the fittings, furniture, and dining room equipment could cost as much as 60 percent of the cost of the building.[17]

Published guides existed to help managers decipher the commercial metabolism of the United States, but most hotel owners and managers relied as much on hunches and personal experience.[18] While bargaining on a lease for a hotel with a bar and dining room, the astute hotel manager counted on the bar for positive cash flow. Dining rooms, other food service, and hotel entertainment offered virtually no chance for profit; at best, they broke even. The bar, however, generated a hefty share of the hotel's income and often paid rent, heat, and light for the whole building. Similarly, store rentals on the ground floor often carried the hotel's interest charges and some of the mortgage principal.[19]

Managers needed leadership ability, sound judgment, and good legal counsel for the daily demands of coordinating a complicated staff. At a polite hotel, that meant a 24-hour supply of maids, bellboys, elevator operators, kitchen assistants, janitors, and plumbers, along with a sizable number of clerks and midlevel supervisors. Much of the hotel management literature chronicles labor strife and methods to reduce it. To keep good workers nearby, builders of large hotels often constructed rooms in the attic or at the back of the hotel as living quarters for a share of the employees. Owners of gargantuan hotels like San Francisco's Palace built neighboring rooming houses with one hundred rooms or more, largely rented to their staff. Rooming houses and cheap lodg-

ing houses required a smaller but equally essential supply of maids and repair people.

Besides assuring the necessary staff support, the motive of a hotel manager was filling as many rooms as possible every night. In 1930, a hotel management report put it this way:

Hotel business differs from the general run of manufacturing in the perishability of its product. Time . . . is the major item that a hotel man has for sale. Every unsold room in his house every night represents an irretrievable loss, for that night will never return.[20]

To attract and keep permanent residents, managers of all types of hotels had to give appropriate attention to their clients, and the manager-tenant relationship was often very personal. Palace hotel managers personally assured wealthy clients that they would have the same suite each year and welcomed them with flowers and a personal note in their room when they arrived. Other managers chatted with tenants daily, or if they were managing a rooming house with elderly residents they helped them read and write letters, do their shopping, make doctor's appointments, or arrange ambulance service. At cheap lodging houses, good clerks made a point of greeting tenants by name and playing host to the group in the lobby to give them a sense of belonging and being at home (fig. 6.6). During strikes, rooming house keepers won loyalty from tenants by extending credit until the strike was over.[21]

When Prohibition cut off bar receipts, even more of the manager's attentions went to maintaining high room occupancy. By the 1920s, in a larger hotel a room occupancy rate of 70 percent was usually needed to break even. Seasonal changes in occupancy were another cash flow reality. When transient guest numbers were low in most palace and midpriced hotels, managers often took in more permanent guests. Monthly room rates were always substantially lower than the prorated daily or weekly rates—often only a fraction of the daily rate—but nonetheless managers could count on that residential income to cover fixed operating expenses.[22]

On similar sites, hotel buildings were known as potentially higher income properties than apartment buildings. Hotels made less money than apartments during business troughs but much more money in busy seasons. Apartments usually offered relatively steady cash flow year-round.[23] After 1920, real estate investors with a small amount of

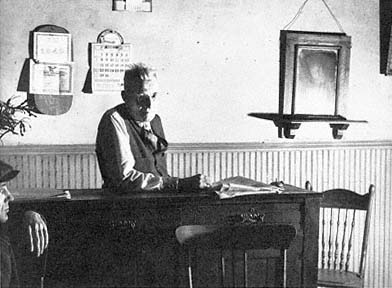

Figure 6.6

Desk clerk in a cheap lodging house in Dubuque, Iowa, photographed in 1940.

Note the casual arrangement of chairs.

capital, or those who wanted to rely on a housing investment as a significant part of their day-to-day income (for retirement income, perhaps), seem to have preferred apartments over hotels.

In the 1890s, the majority of the midpriced family hotels in San Francisco were run by women managers, and women managers were also reasonably common in other types of hotels. A California journalist explained in 1892 that the woman in business may have been questioned in some quarters, but "as a manager of large family hotels and rooming-houses, she is an eminent success" (fig. 6.7).[24] In 1900, up to 95 percent of American rooming house keepers were women. In most cities, about half of these rooming house operators were widows; the married rooming house operators typically had husbands who were wage laborers. Income from small rooming houses was more touch and go than at larger hotels. Unless the woman owned the building, its revenue was not substantial. The small rooming house operators leased their building by the year and bought the furniture on time payments. Typically, both the lease and the furniture purchase were arranged through a real estate broker who specialized in such deals and either owned the buildings outright or managed them for investors.[25] In spite of the meager income available, becoming a rooming house keeper was one of the occupations most available to mature self-supporting women before World War II. Older waitresses, for instance, commonly dreamed of leasing a rooming house instead of slinging hash in a cheap

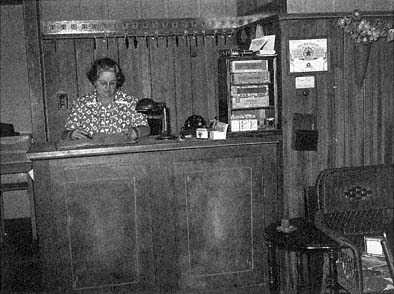

Figure 6.7

Desk clerk in a small rooming house in San Augustine, Texas, 1939.

Even in the nineteenth century, women were commonly hotel keepers.

restaurant. Yet many women went broke in their first year, not realizing the seasonal shifts or other expenses. They lost the money they had paid on the furniture and had to forfeit everything to the rooming house brokers. The brokers then easily found another recently widowed woman willing to invest her small nest egg on a rooming house venture. Rooming house real estate brokerages were so shady that some hotel brokers, to appear reputable, overtly advertised "strict conformance to upright business principles."[26]

Cycles of Investment and Construction

Particular years were noted for surges in all types of hotel investment. San Francisco directories record how quickly the number of hotels changed in response to potential business (fig. 6.8). Peaks of hotel listings coincided with surges in the local and national business climate, particularly in response to increased industrial and office employment, wars or other widespread investment stimuli, and surges in tourist travel. Troughs in the number of hotels corresponded to employment and travel slumps.[27]

Mercantile and industrial expansion—and the ensuing population movement—triggered good business for hotels of all types. The first major peak in San Francisco's hotel listings, from the mid-1890s to 1905, followed production surges for the Spanish-American War, discovery of gold in the Klondike, and increasing Philippine and Pacific

Figure 6.8

Graph showing total number of hotel listings in the San Francisco

directories from 1870 to 1970.

Basin trade. It also coincided with the stimulation of Pacific Coast business due to the promise of the new Panama Canal trade and the rapid growth of population and markets in the American West.[28] San Francisco's great earthquake and fire of 1906 only briefly interrupted hotel business. In the aftermath, a great many hotels were built for workers and for households displaced by the destruction. No drastic land-use changes occurred in the rebuilding; the fire merely hastened and highlighted gradual developments already under way in real estate investments for the center section of the city.[29] At the scale of individual lots, the average hotel business before the fire had about 30 to 60 rooms; after the fire, each business listed in the directory was more likely to be on a lot twice as large and to have from 40 to 100 rooms.[30] Thus, although the number of individual hotels in San Francisco peaked in 1906 (the year of the fire), the peak in hotel rooms came after World War I.

Hotel keeper E. M. Statler called World War I "the best five years American hotels ever had." (He could not have imagined the boom of

World War II.) Wartime meant expanded employment. New hotels of all ranks were built or converted for war demands, and each wartime boom stretched all existing hotels to their maximum potential—and sometimes beyond. War industry workers packed into lodging houses and rooming houses while the better hotels did thriving business with war-material brokers, production engineers, government officials, and military officers. The only single-room housing operations that languished in World War I were the free municipal lodging houses and other flophouse adjuncts in some cities, which were made less necessary by high wartime employment. The Chicago Municipal Lodging House closed entirely in 1918 –19 because of lack of applicants.[31]

After World War I, generally, only the directors of philanthropic rooming houses (such as new YWCAs) and owners of midpriced and palace hotels added to the stock of hotel rooms. Again, the San Francisco case is typical.[32] From 1918 to 1921, manufacturing employment decreased in San Francisco industries by 4,000 employees, down almost 10 percent; by 1925, it had dropped by another 4,000. Hence, private downtown housing investors in San Francisco built neither lodging houses nor rooming houses after World War I. A share of this downtown decline also resulted from mechanization in the work place and the steady relocation of industries to the edge of the city.[33]

Within these broad swings in hotel business, several market processes operated. Perhaps the least rational were those behind the building of palace hotels and some midpriced hotels. Beginning in the 1820s, each generation of city business leaders felt compelled to adorn their town with a state-of-the-art hotel—usually larger and more lavish than strictly necessary—to assure their city's regional or national stature. In the 1920s, palace hotels began to vie even with office skyscrapers as the largest buildings in major cities. Not all of this was sheer boosterism. For two centuries Americans have responded positively to size in hotels as they have responded to size in other commercial attractions. The biggest hotel in town also commanded monopoly rates and the largest conventions.

In the battle between city boosters in different towns and between different expensive hotels, design and fashion as well as size figured prominently. As the competition between a city's better hotels increased, the owners and managers came to rely more on the tools of high-style design, attention-catching interior decorating, spectacular

cooking, and innovative engineering. In every generation, owners and their architects informally settled on a prevailing facade style for hotels; for interiors, managers and their designers changed the reigning style almost twice as often. Thus, to remain in fashion, hotel managers had to search for better chefs constantly, redecorate about every ten years, and significantly remodel or add new wings at least once every twenty to twenty-five years. Watching the constant competition between grand hotels, Sinclair Lewis observed that "next to love, nothing loses its rank so quickly as a leading hotel."[34]

When hotel owners demanded ever-larger hotels to pay for evermore-expensive downtown land, architects responded with new types of floor plans. On larger sites, designers provided wings of rooms separated by larger and wider light wells. In an "E" or "C" shape, the floor plans yielded more rooms with two- and three-way exposure for better cross-ventilation and light. Engineering also set new hotel fashions. For every passing decade's conspicuous innovative gadget—calling-card elevator, exuberant lighting display, ice water tap, or built-in radio—managers installed many more machines to reduce labor costs. By 1900, the design and outfitting of hotels had become complex enough so that a few architecture and engineering firms specialized in hotel design and did a significant share of the nation's large hotel business.[35]

The use of elevators particularly revolutionized hotel life. With elevator access, the rooms on upper floors (once the cheapest rooms) became the most expensive. By the 1920s, tower views from high palace hotel rooms had become another aspect of hotel living that expensive private houses could not outdo.[36] In San Francisco, it was George Smith who best captured the skyscraper view. In 1939, to compete with new post-Prohibition bars and nightclubs opening throughout the city, he opened the Top of the Mark at the remodeled crown of his hotel, where a penthouse apartment had been. Smith also hired the talented architectural office of Timothy Pfleuger to give the Top of the Mark the Manhattan sheen of Art Deco style.[37]

Managers who chose not to compete in the size, chef, or gadget game typically dropped their hotels to a lower rank of clientele by cutting the amount of service, closing lavish dining rooms, or changing from American plan to European plan rates. With such cuts in service, a palace hotel could be profitably run as a midpriced hotel. In the late 1920s, so many boosters had built so many good hotels that in most cities

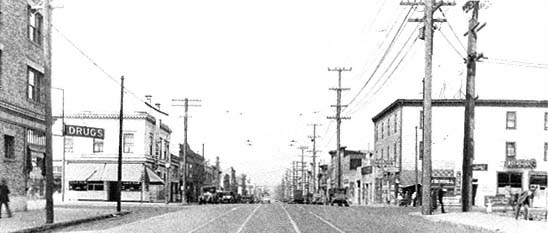

Figure 6.9

The Gateway District of Minneapolis, photographed in 1939. Through the filtering of clients, this Victorian

midpriced hotel district had shifted to cheap lodging house status.

there were price wars and substantially lower transient occupancy rates. Simultaneously, motels and auto courts were beginning to cut into the family travel market. Such overbuilding stimulated more permanent occupancy to fill the rooms. Managers lured tenants with ads proclaiming, "Occupancy from October! Lease from January! Fifteen months for the rent of twelve."[38]

For all types of hotels, shifts of social cachet, demographic changes in surrounding neighborhoods, or losses in nearby employment triggered the process of filtering: first, former permanent guests gradually filtered out to newer, more comfortable, or better-located quarters; second, to keep occupancy levels high, managers at the older hotels lowered their prices, allowing less affluent tenants to filter in; finally, the remaining earlier tenants left, feeling that their social standing, comfort, or safety was in jeopardy. In any American city, it was not unusual in the 1920s to see handsomely designed and fashionable family hotels of the 1880s that had devolved to inexpensive rooming houses for unskilled or unemployed workers.[39] Cheaper hotels, too, filtered to lower-income tenants (fig. 6.9). In the core of San Francisco's South of Market

district, the managers of several hotels built in 1906 had by 1919 discontinued polite hotel services and given up the term "hotel"; they simply ran their establishments as more casual rooming houses or lodging houses. On one block alone, three out of four hotels had seen this conversion.[40]

To maintain high profits in spite of lower rents, owners of rooming or lodging houses could reduce repair budgets and employ only minimally skilled managers or staff. What observers called the "visual decay" of rooming house districts was usually the evidence of inept or uncaring management and the literal erosion of architectural fabric: first cosmetic facade deterioration and then more serious structural dilapidation from decreased maintenance.[41]

Like the question of when to launch a new hotel business, the question of when to leave the hotel business was often prompted by the general urban metabolism and how it affected the neighborhood, hotel clientele, competition for the hotel site, and the cash flow of the property owner(s). If hotel managers could not sell their rooms to either tourists or permanent guests, and if shifting to cheaper clients did not work, owners often looked to office rentals or other nonhotel uses. At appropriate downtown locations hotel owners could rent rooms, whole floors, or the whole hotel as offices. Even in colonial times, hotels had mixed offices and sleeping rooms. In 1906, the Grand Central Hotel in San Francisco was consciously built to be either office or hotel space, and it saw both uses. The elegant Hotel Whitcomb served as San Francisco's city hall for a time after the great fire. About 1920, the owners of New York's Manhattan Hotel (even though it was the birthplace of the Manhattan cocktail) converted the twenty-four-year-old building to offices. Other hotel owners converted their properties to private hospitals (or vice versa). After 1945, however, demands for better electrical service, lighting, and air-conditioning made such office and hospital conversions less feasible.[42] When all else failed, a major old hotel's downtown site usually brought the owners a good price as the location for a new office tower. The most notable example of such conversion is the block that held the original Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, where the Empire State Building now stands. At times even perfectly profitable and viable hotels were torn down, revealing tensions that can exist between owners and managers. If the owners were convinced they could profit

more by closing the hotel and changing the building's use—and if the managers had lost their lease—no basis remained for the hotel to be in business, other than emotional appeals by the managers or clients.

Especially at the scale of the Empire State Building but also at more modest sites, the actions of individual owners and managers had a great influence on the surrounding blocks. Hotels collected large numbers of people who were a market for other retail services nearby. The hotel's staff also exerted a pressure for their own housing and for their retail needs. These influences, plus their voice in urban governance as landowners, gave hotel builders important roles in rebuilding downtown neighborhoods in a more organized way.

Specialization for Single Use

At the turn of the century, downtown renters and landowners were actively rejecting mixtures of different people and activities that had been common and widely accepted as late as 1880. In the old city, even plutocrats proudly built their mansions on streets that included middle-income people and plots with inferior improvements and wildly varying qualities. Not even the most wealthy could guarantee a proper setting for their homes (fig. 6.10). Noxious factories could blight nextdoor flats or tenements. From their own perspective, factory and workshop owners saw nearby dwellings as a blight; as industries expanded their production, they needed larger unencumbered sites and fewer neighbors who complained about smoke and noise. With less mixture and more logical land-use patterns, private downtown builders and clients hoped that business growth might be more predictable, employees healthier, and clients more conveniently available. In such a reformed city, future property and business investments would also be more secure and less threatened by the encroachment of slums. Sites would be assured of maintaining their "highest and best use"—usually interpreted to mean their most valuable use for private return within some rational sense of the public good. The timing for this desired shift in land-use attitudes hinged on the growing size and complexity of cities, new industries, traffic problems, and the social and cultural repercussions of high-density mixtures of different people and competing projects.

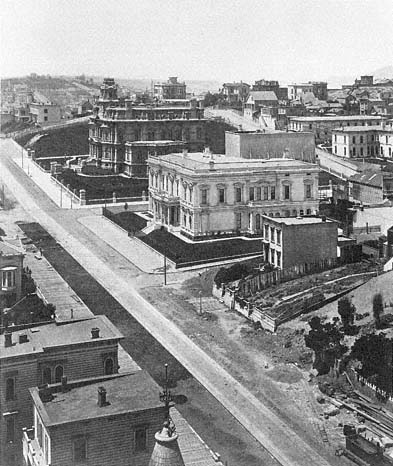

Figure 6.10

Residential land-use conflicts on San Francisco's Nob Hill during the 1870s.

In the foreground, the white mansion of the Southern Pacific Railroad's chief

lawyer stands next to a very ordinary 1870s middle-income row house. At the

rear is the Victorian pile of the Crocker mansion. Crocker wanted to own his entire

block to properly distinguish his home. His last remaining neighbor refused to sell,

so Crocker built a 30-foot wooden "spite fence" around the parcel. Photographed

in 1878 from the tower of the Mark Hopkins mansion.

Privately, on new land at the edge of the city developers could impose covenants or simply own tracts large enough so that rational control for the owners' best interest was guaranteed. Publicly, cities did not have the legal power to enforce greater separation and organization until the 1920s. Instead, downtown builders privately replaced the old city's heterogeneity on a site-by-site basis, gradually and informally creating more specialized zones. By the 1890s, rudimentary district specializations—industrial apart from commercial, commercial apart from residential, workers apart from middle-income people—were becoming fairly implicit goals of private city building.[43] Hotel owners played their part. As they changed their individual properties they not only helped to specialize hotel life but also whole districts in which those hotels stood and, inevitably, the nature of living downtown.

In the gradual drive for specialized urban space, hotel owners first specialized designs for distinct hotel building types. From the very earliest experiments, palace hotels were purposely built as permanent and unique parts of the city. In 1829, the architect Isaiah Rogers had designed the Tremont House in Boston as a monument, just as George D. Smith demanded that his architect make the Mark Hopkins a singular monument on the San Francisco skyline. However, from 1880 to 1930, San Francisco's other types of hotels varied widely in the specialization of their buildings (fig. 6.11). In 1880, over a tenth of San Francisco's midpriced hotels were still in reused grand houses. By 1910, all operators of midpriced hotels were in structures intended solely for hotel uses, probably reflecting their clients' higher expectations for private bathrooms and the rebuilding from the fire of 1906.[44]

Before 1900, as a rule, developers made cheap hotels a less permanent part of the city: the lower one's social status, the more impermanent was one's hotel. Compared to the investors in expensive hotels, the actions of San Francisco rooming house investors provide an apt case of slower specialization. They chose architectural flexibility so that if the hotel scheme did not work, they could easily use the structure for something else. In 1880, half of the rooms in the city's rooming houses occupied the upper floors of fairly undifferentiated commercial structures. The building envelope provided few or no housing-style amenities such as light wells or other residential adaptations. Rooming house owners changed their minds rapidly at the turn of the century, probably spurred by client expectations raised by improvements in single-family houses. In 1910, only 5 percent of the rooming house rooms were in general-purpose commercial buildings. At that same time, 17 percent of rooming house rooms were in converted houses due to the dislocations of the fire. By 1930, owners had rebuilt many of their properties, so that 90 percent of the people in rooming houses lived in specialized buildings, not ad hoc structures. By that year, landlords had also increased the average size of a rooming house to about sixty rooms—twice the 1910 average.

Predictably, the slowest architectural specializations came in hobo hotels. Up until the turn of the century, only a small share of San Francisco's cheap lodging house rooms were in buildings constructed for that purpose; more often, owners of a downtown house or commercial loft building roughly converted it for lodging house use. The temporary

Figure 6.11

Increasing specialization of San Francisco hotel buildings. Note especially

the number of rooming houses and cheap lodging houses in ad hoc structures

in 1880 and 1910.

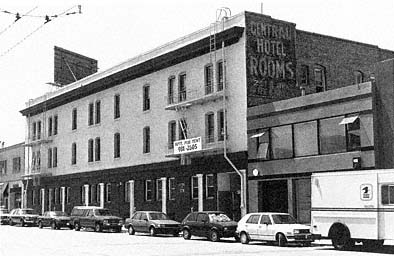

Figure 6.12

An example of a specialized cheap lodging house built in 1909.

The Central Hotel, built by Edward Rolkin at Third and Brannan

in San Francisco, had 440 small rooms and several storefronts

across the first floor, including a large saloon and dining room.

It was later converted to apartments as shown in this 1992 photograph.

arrangements built for the lodging house residents reflected many things: their marginal rent-paying ability, the lack of housing inspection or adequate health inquiry for these groups in San Francisco (true in most other cities as well), and the condescension of landowners toward their tenants. Also, owners of downtown land acted as if they hoped and expected that the laborers would soon go away. Because of its central location or location adjacent to industrial areas, the land under cheap lodging houses was still considered too valuable to devote permanently to casual laborers. By about 1900, however, perceptions were very different. Many landlords had realized that lodging house residents were a permanent group and that it made good economic sense to design buildings especially for them. San Francisco's Edward Rolkin became a leader in this process as he rebuilt his properties after 1906. He assembled larger sites around his best lots and hired inexpensive architects to make the largest and most particularized hotels San Francisco's laborers had ever seen: brick bearing-wall structures like that of the Central Hotel (fig. 6.12). On other lots, owners were doing the same thing—but not all the owners, since in 1910 a third of the cheapest hotel rooms were still in temporary loft-type quarters, often with completely wooden construction. Nonetheless, by the end of World War I, virtually all lodging houses in San Francisco were purpose built at an average size of about sixty rooms each.[45]

As noted above, for owners, the better facades of cheap hotels were fronts for embarrassing realities. For residents of inexpensive hotels af-

ter 1900, being in a purpose-built hotel (rather than an ad hoc adapted house before 1900) usually meant better physical conditions: wider light wells, better ventilation, and private room sinks. Specialized cheap lodging houses had at least the required minimum of a one to twelve ratio of baths to cubicles. San Francisco's city administrations varied notoriously in ability and honesty and started effective building regulation comparatively late. Nonetheless, by the mid-1910s sporadic enforcement of the city's regulations had begun and may account, in particular, for the increase in minimum standards in lodging houses by the time of World War I.[46]

For city residents in general the new, larger, and more specialized rooming houses and cheap lodging houses made a distinctly different visual impact on the streets of the city. Compared to their predecessors, the new hotels were often taller, located on more prominent corner sites, and more visually insistent. The large painted advertisements on the structures' blank sides announced the availability of steam heat, low weekly rates, locational advantages, and often a nearby ice cream parlor or clothing emporium. The new visual impressions of these more architecturally defined structures were also surrounded by more particularized neighborhoods.

The organization and separation built into individual hotel buildings were parts of the larger specialization of whole neighborhoods. Hotel owners hammered out more distinct hotel districts from 1880 through 1930, each with a different range of services. Palace hotel builders learned to keep their buildings and neighborhoods more exclusive and insular by putting most tailor shops, newsstands, and restaurants into interior arcades.[47] Meanwhile, designers of midpriced hotels and cheaper apartments kept equivalent services open to the sidewalk.

San Francisco's Western Addition became an old-house rooming district in an uneven process but one that was typical of rooming house areas in other American cities. From 1900 to 1930, people in the property industry seemed to disagree about whether the Western Addition was becoming a converted-house district, an area of new purpose-built rooming houses, a zone of middle-income apartments, or simply a slum. After the fire of 1906, many neighborhood landowners converted their large Victorian era houses into rooming houses to serve emergency needs; within a few years, a good number of these people had converted their houses back to single-family use—either as rentals or

for their own homes. Others, however, built rooming house additions on their lots, creating a diverse mixture of rental conditions and lower prices. These attracted new residents and increased the area's ethnic and racial diversity. Meanwhile, through the 1920s, other developers assumed the area should resemble lower Nob Hill; they speculated in large lots, built tall apartment buildings, and drove up land values. Finally, during the building hiatus of the depression, the slum perception took over. The majority of the house owners had moved away; absentee owners could not rent out large units. They converted their houses to flats, ad hoc apartments, or light housekeeping rooms and stopped investing in repairs or improvements. They held on to their Western Addition properties, hoping for a resurgence of land values. As the perception spread that the area was indeed a slum, more owners individually shifted to rooming house and light housekeeping use. During World War II, Japanese families were removed to internment camps, and the black population in the area increased from 5 to 30 percent. Through 1945, the rents were high enough to make these income properties too expensive for San Francisco's housing authority to acquire, but the area had been officially tagged as a problem zone. Neither property leaders nor planners had a positive view of a good rooming house zone being developed in the Western Addition, although in the 1920s that had been a viable future for the district.[48]

In similar ways, individual landowners specialized skid row areas but usually without the vacillation that marked the Western Addition. The concentration of cheap lodging houses in the Third and Howard area in the South of Market was a steady progression. In 1880, only about a third of the residents in that area had rented rooms in family homes or hotels. By 1900, that proportion had increased to one-half, and it continued to grow. By the late 1920s, the most densely settled blocks of San Francisco were no longer in Chinatown but in the blocks of lodging houses clustered at the core of the laborers' zone.[49]

The individual changes wrought in the South of Market responded to changes in industrial employment from both the invasion of new uses and the retreat of former residents. From 1880 to the mid-1920s, distant railroad and agricultural projects throughout the West became larger, and the number of hobo laborers increased, doubling and then tripling the San Francisco cheap hotel market. In 1900, San Francisco's South of Market area still had many ethnic families and commercial

Figure 6.13

Workers' hotels vying with downtown offices in permanence and prominence. The last two blocks of

Third Street in the South of Market, looking toward San Francisco's financial district, 1929.

family services located on side streets or alleys, mixed with small lodging houses and rooming houses. As owners of industrial facilities bought up land and as family-tied workers moved to be closer to new skilled work sites, family services began to be more scarce. Astute lodging house owners like Rolkin were ready to buy up any available lots. By 1930, lodging house developers had cornered most of the major sites in a wide area around Howard, Third, and Fourth streets. The massing of building along the major streets was impressive (fig. 6.13).

As single workers' zones became more separated, organized, and specialized, there were fewer reasons for other city residents to enter them. Workers' zones became the most alien and repugnant commercial districts in the city for middle and upper class suburbanites. Sinclair Lewis presents George Babbitt as a real estate man who knows most of Zenith building by building—especially central and suburban Zenith. However, for Babbitt the workers' zone (where he goes to buy bootleg gin) was merely a "morass of lodging houses, tenements, and brothels."[50] While the effect of specialization of San Francisco's Howard and Third streets made them alien to suburbanites, the process had

Figure 6.14

A small corner hotel at Pacific Street and Powell, in San Francisco, 1926.

a different effect on male low-income laborers who lived elsewhere. Areas like Howard and Third remained familiar haunts for their evenings away from their new homes in the cottage districts. The South of Market concert saloons, billiard halls, and other establishments were places where they felt at home—a sense they had in few other districts in town. The neighborhoods were also fertile ground for union activists and liberal and radical political workers.

For the property industry, collectively hammering together fashionable hotel zones, rooming areas, or single laborers' zones helped to ensure steady real estate income. Another effect of specialization was the prominence it gave to outlying experiments in hotel life at the turn of the century; they became more prominent because they became more exceptional. Throughout the nineteenth century, a few rooming houses with public dining rooms could be found in fairly scattered locations in middle-income and working-class neighborhoods. By 1900, these hotels in outlying streetcar districts were more concentrated. Commercial nodes at the intersections of two lines typically had three or four hotels or rooming houses built above corner grocery stores and other neighborhood shops (fig. 6.14). The neighborhood hotel could be a place for Sunday dinner excursions. Proper single-family houses might also have had a hotel as a neighbor. Especially before 1920, a few landowners with property close to a major avenue expanded the residential capacity of their lots by building a residential hotel much larger than

Figure 6.15

Experimentation with hotel life in formerly prestigious residential areas, photographed in

the 1940s. The large H-shaped Belmont and Buckingham apartment hotels, top left ,

replaced former mansions on half of a city block in Denver's Capitol Hill district in 1917.

Developers built the other apartment buildings a generation later.

the surrounding houses but not above the two-story height of the neighbors' houses. Elsewhere, the site of former mansions provided space for large new apartment hotels (fig. 6.15).

Not everyone heralded the specialization of hotel buildings and downtown housing districts as a desirable change. The more definite building types of hotels, the more definite neighborhoods, and even the outlying experiments were problems for some urban critics, usually people outside the property industry. The criticisms and concerns also had a definite class bias: examples of hotels built and managed for the middle and upper class were often treated very different from hotels built for the working class, and the concerns were rooted in street perceptions.

Public Impressions and Residential Opposition

Within San Francisco's development and specialization, George Smith and Edward Rolkin lived and worked in widely separated spheres. Smith, through his success in elegant downtown hotels, became a lead-

ing booster of the city. He was vice president of the Golden Gate International Exposition, a director of the Chamber of Commerce, president of the Downtown Association, and treasurer of the San Francisco Convention and Visitors Bureau. He retired in 1961 at seventy-two years of age and sold his share of the Mark Hopkins for a reputed $10 million.[51] As true urbanites, after retirement he and his wife moved to a fashionable downtown apartment near Union Square. Rolkin, an immigrant, never fully retired and personally managed his string of hobo hotels until he died in 1941 at the age of ninety, a social outsider with a real estate fortune of $2 million. He had served on the California State Board of Equalization, but his most important social or civic organization seems to have been the Independent Order of Oddfellows. Rolkin's obituary dubbed him the "Landlord of Skid Row."[52] Although both Smith and Rolkin trained themselves, built large hotels, and personally managed them, they remained in the two separate worlds of residential hotel life: on the one hand, the culturally acceptable; on the other, the merely necessary.

Most middle and upper class citizens came to perceive the negative, necessary side of hotel life far more clearly than its positive, more culturally acceptable side. The specialization of hotel buildings and districts as well as the lives of their residents helped to exacerbate the negative public perceptions. In the 1880s, downtown housing and the mixtures of the old city comprised a large share of San Francisco's extent. In addition to the downtown core, a third or more of the residential neighborhoods still had occasional commercial single-room housing and retail uses. In those large areas, such mixture was a part of everyday urban experience (fig. 6.16). By 1930, the city's number of hotel rooms had quadrupled; the ratio of hotel rooms per person in the city was substantially higher than in the 1880s. The concentration of hotel life in the downtown core had expanded significantly. However, outlying neighborhoods with an occasional residential hotel represented only a tenth of San Francisco's extent. The new city of more single-purpose areas—areas for only residence or only production—stretched for miles. Thus, by 1930 one of the most salient features of downtown housing had become its dramatic contrast with the outlying residential districts. Together, the expensive and cheap downtown residence zones comprised an island of urban life very different from that in the rest of the city.[53] People outside the suburban family model or

Figure 6.16

Comparison of the extent of old city mixture in San Francisco, 1885 and 1930.

As the city grew after 1900, dense mixtures of housing and commercial

activities became a much smaller proportion of the city's total area.

who chose family life in an old city mode were increasingly concentrated downtown.

The gradual architectural specialization of the city from 1880 to 1930 helped to make positive hotel life less visible to people of the middle and upper class (as was the case with George Babbitt) while it made negative hotel life more visible. As always, well-dressed middle-income hotel dwellers melted into the downtown crowd.[54] Meanwhile, for well-to-do citizens the people who symbolized social and personal failure became more vividly associated with hotel homes. While a relatively small percentage of successful people were known to live in hotels, a very high proportion of hoboes, poor single clerks, drunks, and prostitutes were known as hotel residents. From the carriage, streetcar, or automobile one was far more likely to remember a bum who had passed out in front of a cheap lodging house than the happy thirty-year-old clerk walking to his rooming house. Among single-family house dwellers, the best-known aspects of the cheap hotel zones became their culturally questionable recreational pursuits. In zones of converted houses, the ROOMS TO RENT signs and the rooming houses

they represented came to be seen as the cause of urban blight rather than the side effects of underlying migration, layoffs, real estate speculation, or expansion of the business district.

The new permanence of the downtown housing districts was even more significant than their specialization. As downtown landowners like Rolkin and the various Pacific Heights professionals built their larger buildings on more prominent street corners, they announced that the alternative hotel life-styles were not a passing phase. The downtown housing areas were not, as one Chicago sociologist had labeled them, a "zone in transition." The owners of the new brick, steel, and concrete residential hotel buildings had clearly built for at least sixty years—the same life expectancy of the adjacent office and loft buildings. The permanent residential interiors of the new hotel buildings signaled the potential for a long-term zone of opposition to the cultural ideals behind the new city. In 1917, the California state senator, Lester Burnett, used dire predictions of persistence to exhort his colleagues to pass a stronger housing act. Where "only apartment houses, hotels, and lodging houses are built," he said, referring to San Francisco, "the city blocks are becoming a mass of buildings of steel and brick so solidly constructed as to last a century or more ."[55] At the time of the San Francisco fire, Senator Burnett might have seen the city's ad hoc wooden hotels as temporary necessities, a passing urban phase. Like the shanty city required for the workers who built the gleaming new capital of Brasilia, San Francisco's minimal hotels had seemed a necessity for the building and rebuilding of the new city. When the city was finished, Burnett and others felt that the cheap lodgings would collapse like packing crates and that their denizens would go away or somehow move to new single-use suburbs. However, when the workers' housing became permanent—"as to last a century or more," as Burnett put it—observers became alarmed (fig. 6.17).

The specialization of downtown buildings also fueled the separation between the culturally acceptable and merely necessary hotel realm, as shown in the careers of George Smith and Edward Rolkin. Smith knew the polite hotel's need for skilled managers. At the end of his life he generously endowed San Francisco's professional hotel and restaurant school, which was named after him. Rolkin left a substantial sum to an agricultural school in Poland but gave nothing to train managers of cheap lodging houses; academically trained managers were not part of

Figure 6.17

Temporary versus permanent structures in San Francisco's South of Market district.

The simple wooden rooming house (right ) contrasts with the brick housing

structure (left foreground ) at Folsom and Ninth streets, 1927.

the concept of running low-caste hotels. New clerks got only on-the-job training, as is still the case today. The distinct social relations of Smith's and Rolkin's hotel worlds meant that Smith enjoyed fraternal relationships with his customers, while Rolkin had paternalistic relationships with his. Smith, an avid golfer, advised Mark Hopkins guests on the local courses; Rolkin left a sixth of his estate to purchase candy, tobacco, and other treats for the residents of the county relief home, many of whom would have been his former tenants. The hundreds of absentee hotel landlords in San Francisco had even less direct relationships with their clients than Rolkin. However, they did leave distinct regions of the city that they had collectively built.

Rolkin knew that he was operating marginally reputable businesses—at least in the view of middle and upper class culture, yet he died during World War II with his hotels at absolute peak capacity. To that same polite culture, Smith seemed beyond reproach. Oddly, Smith lived to see the unraveling of the residential life that he had built into the Canterbury, Mark Hopkins, and Fairmont hotels. He also saw one of America's first giant urban renewal projects of the 1950s raze most of Rolkin's properties and guarantee the value of his own. The work of both Rolkin and Smith came to be attacked for threatening the cultural and social life of San Francisco. As both of these men built, leased, and traded hotels they had also unconsciously been generating opposition to their investments. They were "current capitalists" willing to "try the experiment of a civilization without homes." At stake were more than profits or architecture. The grander cultural critique had to do with

how "home" was to be defined in the United States, in how many different ways, and by whom.

By 1970, a generation after Smith and Rolkin's time, many of the downtown real estate assumptions that seemed so permanent in the 1920s had evaporated. People had stopped building outlying hotel experiments by the time of the Great Depression. The confident Nob Hill/Gold Coast/Upper Fifth Avenue projections for elegant residential hotels also were unrealized. By 1970, the current capitalists of America, in Calhoun's terms, seemed suddenly not interested in the experiment of a civilization without homes. The broad cultural critiques of hotel life, seemingly ignored by the owners and managers of hotels, were to play a major role in that change.