The Migrant Workers' South of Market

San Francisco's huge district south of Market Street had several neighborhoods within it, most of them packed with immigrant families living in tiny cottages and threeroom flats. Before World War II, the area was overwhelmingly white. In 1960, the population of the district was still over 75 percent white, with 14 percent black and 9 percent Asian. The South of Market flour mills, sawmills, refineries, printing plants, and machine shops generated large numbers of jobs for skilled workers and unskilled casual laborers.

Outsiders knew Third Street and Howard Street as the South of Market; these streets were the core of the casual workers' South of Market (fig. 5.16). Migrants often arrived in the railroad freight yards and walked north along Third Street. By the time they reached the corner

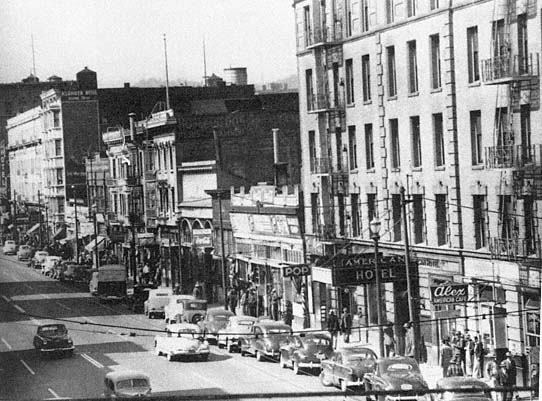

Figure 5.16

Third Street in San Francisco, 1953. Above the first floor virtually every building is a workers' hotel built

before 1920. Today, this is approximately the location of the Moscone Convention Center.

of Third and Howard they would have found all that they needed to be at home for the day, week, or month. A 1914 survey estimated that 40,000 single men lived in the South of Market at the peak of the winter, and half of the city's cheap lodging house rooms were in the district.[52] About a third of these men were permanent city residents.

By the turn of the century, Third and Howard streets were a typical single and migrant laborers' zone, a place that mixed cheap work, cheap rooms, cheap liquor, and cheap clothes. At its heart were multiple employment agencies in rented storefronts. Seven major employment offices competed next to each other on Howard Street between Third and Fourth, a very long block that is the site of the present-day Moscone Convention Center; other, similar agencies were located in the surrounding blocks.[53] Early in the day and in times of high employment, the agency clerks filled their shop windows and the interior walls with chalked placards listing jobs. At the beckoning of "800 HANDS TO COLUSA—SOUTHERN PACIFIC RR" or "40 SHOVELERS—4TH STREET," the men would be off to work for the day or the month. Outside the

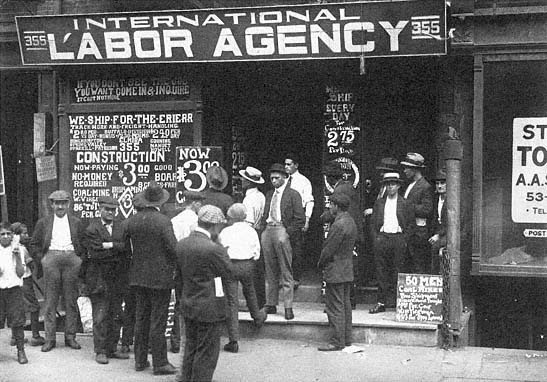

Figure 5.17

A labor agency on New York City's Lower West Side, 1910.

labor agencies men would stand and wait to register for work or for other listings to appear (fig. 5.17). In 1907, Nels Anderson and a friend stood on Omaha's great hobo employment center, Douglas Street, and estimated that they could see a thousand men on the streets and sidewalks. In slack times, the sidewalks outside the labor agencies were still the prime outdoor loitering and meeting spots of the workers' zone. People often loitered on the sidewalks throughout the year in such districts because there was no place to sit other than in a bar, card room, or other commercial establishment.[54]

Other prominent elements of the South of Market were working-men's saloons. Along Third, men found the greatest concentrations of workers' saloons, many with back room "bookie joints" that were legal until 1938. By 1910, San Francisco's saloons no longer served a free lunch, but they offered hearty 10-to 15-cent meals with the purchase of a glass of beer. Nearby were a distinctly grubby class of pool rooms and penny arcades. An occasional amusement hall, concert saloon with its cheerful and gladdening bathing beauties, and later, cheap movie theaters all added to the mix along the ground floors. Upstairs through

much of the zone would be the cheap rooms, cubicles, and dormitory spaces of the lodging houses.

Single laborers' zones also offered essential retail services for the workingman. San Francisco's South of Market had fifty-one second-hand clothing stores, twenty-one of them on the employment-office block of Howard Street alone. Retailers offering new clothing did not do so for "gents," as in the rooming house districts, but called themselves "outfitters": they sold serviceable boots, Levis, heavy shirts, and gloves for distant work camps. Trunk shops and storage locker businesses catered to men leaving town for a season. Radical bookstores supplied reading material aimed at a workers' revolution. A third of the city's pawn shops were also in the district, not far from charity missions and the Salvation Army "institute" or wood yard, which was on a side street. There were barber colleges offering free haircuts, medical and dental schools offering low-cost clinics. Men could also get dental work done on credit in the single workers' zone. In San Francisco, Greek migration was strong after 1910, and the local colony of Greeks began to run South of Market tea- and coffeehouses and inexpensive restaurants frequented by single men. In the evenings, some of the shops offered exotic dance shows. Houses of prostitution or assignation were never far away, but the single workers' zone in any city had fewer women and children visible on its streets than any other residential or commercial district of the city.

Bargain eating shops filled the interstices of the South of Market. Near cheap lodging houses workers always found the most reasonably priced food. A few large lodging houses had inexpensive eateries in them and offered American plan rates to their residents. Most lodging house tenants at the turn of the century, however, relied on saloon fare and the cheapest 5-cent to 15-cent lunchrooms available. For breakfast, San Francisco's Bolz Coffee Parlor promised "three of the largest doughnuts ever fried and the biggest cup of coffee in the world" for 10 cents. Coffee Dan's advertised "one thousand beans with bread, butter, and coffee" for 15 cents.[55] On a crash economy program, a man or a woman could eat three meager meals a day for as little as 30 cents in the mid-1920s. One elderly man gave this minimum-price daily menu:

Breakfast: "coffee and," 5 cents; sometimes with mush, 5 cents extra

Noon: hash, soup, bread, and coffee, 10 cents

Supper: stew, bread, and coffee, 15 cents[56]

At such rates, neither food nor service enticed the diners' palates. Over-worked waiters got plastered with food; stale bread and sour milk were common.[57] The cheapest meals were mission provisions given out free (fig. 5.18).

Life in the South of Market and other American migrant workers' areas began to change in the 1920s because of shifts in the demand for cheap work. As owners mechanized their factory, farm, mine, road-building, and lumber operations, they dramatically cut the need for casual migrant workers. The remaining migrants began to drive rickety automobiles to their work; in Kansas in 1926, for instance, over half the harvest workers came to the wheat fields by car. Having gradually lost the business of robust migrant workers who arrived by train, districts like the South of Market began to be identified more with the home guard.[58]

San Francisco had two other well-known single workers' areas. The Barbary Coast, although much tamed after its rebuilding from the 1906 fire, was still considered a disorderly district. It housed a great number of San Francisco's single sailors and longshoremen.[59] Inexpensive rooming houses and cheap lodging houses dominated the housing supply, mixed with various wholesalers' lofts, bawdy saloons, and houses of prostitution. San Francisco was the base for thousands of military men, and in their off-duty hours they often gravitated to the Barbary Coast (to the chagrin of their officers). After World War II, with the rapid decline of work for San Francisco's break-bulk water-front, the port workers were no longer needed; the recreational culture of the area was seen as an increasing threat. Not surprisingly, the Barbary Coast and waterfront areas were early targets of official and private redevelopment beginning in the 1950s. In the adjacent Chinatown, however, the neighborhood in 1990 stood much as it was rebuilt after the 1906 fire, and had similar uses.