Subsidized Missions

The urban provisions for day laborers and the elderly poor alarmed politicians, philanthropists, and social activists. They waged sporadic campaigns to offer subsidized alternatives to the cubicle and flophouse hotels, just as institutional alternatives were provided for the other hotel ranks. Some attempts were minimal. In the 1890s in Chicago, for instance, the city opened up the floors of the City Hall; on winter nights as many as two thousand people slept there. More commonly, police rounded up (or took in) street denizens in downtown police stations overnight. There, the tenants found stern, clean, and usually unpadded benches or plank platforms for beds (fig. 5.12). Police lodgings served a relatively small group. In 1889 in New York City, only 400 people—half of them women—slept in the police lodgings each night, while an average of 13,000 New Yorkers slept in commercial lodging houses.[44]

Progressive Era reformers lobbied strongly for better public facilities. New York opened America's first municipal lodging house (other than police lodgings) in 1896. By 1902, seven other large American cities had such buildings, and up to World War I the numbers grew. At these, indigents could sleep a few nights on an iron cot and receive two meals

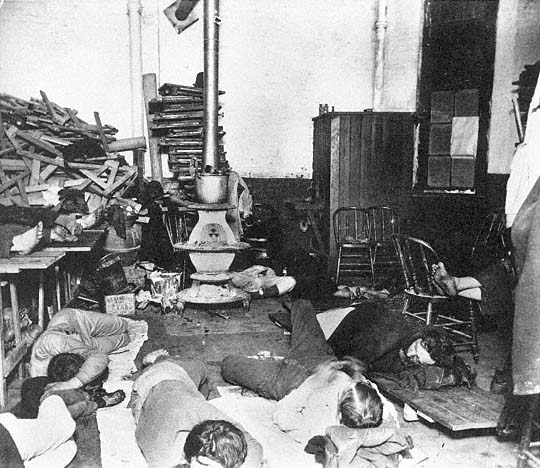

Figure 5.12

The men's lodging room in a New York City police station typifies overcrowding in a makeshift

institutional flophouse. To both sides, note the feet of men sleeping on platforms and chairs.

a day—at least rolls and coffee—if they agreed to put up with interrogation, fumigation, a shower, a promise of docile behavior, and often at least two hours a day chopping wood or cleaning alleys. During periods of high employment, the number of lodgers dropped sharply. During World War I, most cities closed their lodging houses for lack of use; cities reopened their shelters as the rural economy worsened in the 1920s and rapidly augmented them during the depression. By the 1920s in progressive states, counties augmented urban shelters with county relief homes or work farms.[45]

A few philanthropists also subsidized the construction of landmark workers' hotels. The benefactors relinquished the usual 15 percent or more made on urban real estate investments but expected a safe 6 or 7 percent return nonetheless. The most famous East Coast example, the 1897 Mills Hotel built by Darius O. Mills, covered an entire block

Figure 5.13

Exterior view of the Mills Hotel No. 1, built in 1897

as a subsidized lodging house on Bleeker Street in

New York City.

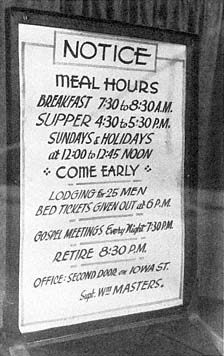

Figure 5.14

Schedules and regulations posted in a

mission window in Dubuque, Iowa, 1940.

front in Greenwich Village and visually dominated the neighborhood. By the 1960s, its social situation had devolved to such an extent that it became the first hotel in New York to be called a "welfare hotel," but that was hardly Mills's intention (fig. 5.13). Its designer, the well-known reform architect Ernest Flagg, included 1,500 well-ventilated cubicle rooms, each five by seven feet.[46] On the West Coast, the palace of workingmen's lodgings was San Diego's Golden West Hotel, a three-story concrete structure of 450 private rooms designed in 1913. While the Mills Hotel is now remodeled as a chic condominium, the Golden West is still a workingmen's hotel. Urban philanthropy standards were also matched at the better company towns built in the United States after 1900.[47]

In 1891, the Salvation Army opened its first U.S. operations in New York; ten years later, they had forty-four missions in the country; by the 1920s, their numerous buildings and enthusiastic marching bands automatically invoked images of a fundamentalist struggle to save souls and to offer free or nearly free beds and food. The Salvation Army was one part of a wide range of missions and shelters that various benevolent groups began to sponsor after the Civil War. Some were simply

basement or upper-floor flophouses, and their sanitary problems rivaled the worst commercial conditions. The field notes about one shelter in St. Paul tersely said, "Charitable Institution. . . . Old Opera House made over; Fire Marshall condemned it."[48]

The supervision in institutional lodging houses was, of course, as notoriously strict as that in municipal lodging houses (fig. 5.14). Institutional lodgings were generally cleaner than cheap commercial lodgings, and they also offered meals, either free (in return for a sermon or prayer meeting) or at very cheap rates. A work shift at San Francisco's Salvation Army wood yard, for instance, entitled men to a bed ticket and a 20-cent meal ticket that could be split into a 5-cent and a 15-cent meal. At the wood yard (a vacant lot) men cut and stacked cords of wood for sale to the public. Some missions also gave out tickets redeemable for meals or lodging at nearby commercial establishments. In a few large northern cities, separate "Negro Corps" were formed; southern Salvation Army services for blacks were segregated until the Supreme Court's decision on segregation in 1954.[49]

For single hoboes, housing options other than cheap lodging houses or missions were slim. Their chance of securing a polite apartment was no more likely than attaining a berth on a luxury ocean liner. Groups of single laborers occasionally ganged together to rent a tenement space and to hire a cook. The places they could get were in the worst tenements or back rooms and cost $1.50 each per week in 1910. In the mid-1920s, a clean-living casual laborer might (with a persistent search) secure a windowless hall bedroom in a low-end rooming house for $2 to $3 a week, probably around the corner from a cheap lodging house. For comparison, a cubicle room or flophouse cost $2 or less a week.[50]