Plain Rooms

The precedents for commercial rooming houses were old-fashioned boardinghouses. Especially before the 1920s, the lines were hazy between a private family house and a commercial rooming house because so many people boarded or lodged with private families. Boarders slept in the house and also took their meals with a family; lodgers slept in the house but took their meals elsewhere. Entire families boarded—often parents or single mothers in their late twenties—but the most common boarders were young unmarried men or women with slim financial resources. Boarding and lodging so pervaded American family life (along with the presence of servants and live-in relatives) that throughout the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, use of the term "single-family house" is misleading. In a conservative estimate for those years, one-third to one-half of all urban Americans either boarded or took boarders at some time in their lives.[4]

Most private families took in one or two boarders at a time. Where more income was needed, a private boardinghouse could have six to ten tenants. Keeping a low profile helped the family avoid the technically required hotel licenses and annual taxes. In such a place, the landlady operated as surrogate mother and father. She wielded authority over parlor life and over curfews and guests. If the old house was a good structure in a decent neighborhood, the residence could be respectable for middle-income families.[5] After 1900, many people looked back nostalgically to these enterprises in comparison to their commercial counterparts.

Former-house Rooming Houses

The commercial rooming house of 1910 was run overtly and officially as an inexpensive hotel. Its manager often paid for a commercial license. The business was in a twenty-five-to forty-year-old house, three or four stories high, originally built for a middle-income family. The owners had moved to the edge of town and leased their downtown house to someone—inevitably a woman—who rented rooms as her chief source of income. The landlady of a commer-

cial rooming house often advertised in her front window with a card reading ROOM TO RENT or FURNISHED ROOMS.[6] Like Richardson, rooming house residents often began their first solo encounter with downtown life as they lugged their suitcases down the streets in rooming house districts and searched for window cards.

Figure 4.2

Second-floor plan for a conjectural

conversion of a large single-family

row house into a rooming house.

Shaded areas indicate where thin

walls have been added to cut up

the large rooms of this 1840s house.

The warren of five rooms at the front

was constructed from the two former

principal bedrooms and their closets.

The typical rooming house had earlier been a boardinghouse. After the Civil War, the number of commercial boardinghouses sharply declined. In 1875 in San Francisco, for instance, boardinghouses made up almost 40 percent of the commercial housing listings in the city directory. By 1900, boardinghouses had dwindled to fewer than 10 percent, and by 1910, they constituted less than 1 percent of those listings. Boston and Chicago saw similar declines.[7] During these declines, boardinghouse keepers were not quitting but getting out of food provision—shifting their businesses from boardinghouses to rooming houses. This shift considerably eased the landlady's life. She could rent out her dining room and parlor as additional bedrooms; she could fire the one or two servants she had needed to provide the meals. Eliminating meal service eliminated the most troublesome and costly parts of her business.[8] In a rooming house, the residents ate their meals with a family down the street or (as was most often the case) in commercial eateries.

Architecturally, the former-house rooming house was usually a fairly large row house with from sixteen to eighteen rooms, including the bath, the laundry, and the landlady's kitchen, if there was one (fig. 4.2). Owners or landladies created extra rooms by subdividing larger bedrooms and parlors and providing approaches to them with dark deadend hallways. Like the attic room that Richardson found in her first week in New York, some rooms had only a transom window onto a hallway, a tiny dark air shaft, or a nonopening skylight. Until after World War I, few of these rooming houses offered central heating; small individual stoves or coal grates served to heat the rooms.[9] The high rents of undivided parlors and dining rooms required two residents to pay for them. The lowest-priced rooms were on the upper floors, with unheated attic and end-of-hallway rooms costing the least. On occasion, owners joined several houses together, creating a single rooming house with as many as forty rooms and seventy tenants.[10]

Chairs—their number, repair, and plushness—indicated any hotel room's social rank. In a good midpriced hotel, three chairs were the minimum; in rooming houses, two were the maximum. At the second

of Richardson's many rooming houses, she listed the furniture in her room: a battered but cheering "tiny mite of a stove," an equally battered wooden bedstead that creaked and groaned at her every move on its thin mattress, a single chair with a mended leg, an evil-smelling lamp with a wick not quite long enough, and a tremulous kitchen table. She longed for simple comforts of more expensive quarters, complaining that there was "no bureau, only a waved bit of looking-glass over the sink in the corner. My wardrobe was strung along the row of nails behind the door."[11] Beneath the row of nails and her few pieces of clothing Richardson stored a wooden trunk, her only piece of luggage.

Most former-house rooming houses offered only the one bathroom built for the original family, whether the house had nine bedrooms or eighteen, six tenants or twenty. Usually the bathroom was on the second floor. To conserve the high cost of fuel, landladies tacked up signs that sternly limited residents to no more than one hot bath per week. The customary plan was to supply hot water once or twice a week, although during the summer, hot water could be unavailable for months at a time. Towels were often in short supply. Residents facing a week without hot water could resort to large public or commercial bathhouses where hot baths cost 10 or 15 cents in 1900. Tenants lucky enough to have a room with a washstand, a pitcher, and a bowl—a pitcher and bowl that were "inevitably cracked"—carried the water themselves.[12]

From one city to another, names and conditions in old-house rooming houses showed only minor variations, one of which was what people called the buildings. In Philadelphia, the common term was furnished-room house; in New York, Chicago, Cleveland, and St. Louis, rooming house; in Boston and San Francisco, lodging house .[13] Since blacks were excluded as guests in most hotels and rooming houses, in many cities, black rooming houses and boardinghouses had a greater mixture of transient and permanent guests than did rooming houses run for whites. Other special cases of converted buildings were converted apartments. Especially after the depression and World War II, entrepreneurs would lease old, eight-room to ten-room apartments and then sublet the rooms individually. All the tenants would share the bath and the kitchen. An entire multistory apartment building could be converted into such single-room units.[14]

Figure 4.3

A Victorian era booster hotel on a small town's Main Street and public square, 1940. By the time of

the photograph, the clients of this Rockville, Indiana, hotel were likely paying rooming house rents.

Building owners also made rooming houses out of run-down palace or midpriced hotels. They eliminated service, repairs, and amenities until the rents matched rooming house levels (fig. 4.3). For example, San Francisco's Central Pacific Hotel was originally built as a midpriced hotel. By the 1880s and 1890s, it commanded only rooming house prices and was home to a wide range of residents. In 1880, behind the five ground-floor shops lived the shopkeepers and their families, 21 people in all. Also on the ground floor were the hotel dining room and lobby. Upstairs were transient guests, along with 42 permanent residents. Fifteen of the permanent residents were the hotel owners, the two servants, and their three families. Of the remaining 27 permanent lodgers, 26 were single adult males, overwhelmingly Irish (as were the owners of the hotel, the Farrells). The lodgers were mostly twenty-five to thirty-five years old, although the range was from a fifteen-year-old blacksmith to a sixty-three-year-old laborer. The depression of the late 1870s had hit these men hard; the average tenant at the Central Pacific Hotel had been out of work for over seven months in 1879–80.[15] Large hotels like the Central Pacific had the advantage of a night clerk, which eliminated the small rooming house's curfew. Instead of the landlady

Figure 4.4

A generic-loft rooming house, built about 1880. The Frye

Rooming House near Chinatown in San Francisco was

adjacent to a cigar factory. The upper floors, with 16 rooms,

could easily be converted to other uses. The fenestration is

conjectural.

locking the front door at ten or eleven at night, the doors of a large hotel were open around the clock. Late tenants did not have to rouse an angry or inquisitive manager.[16]

In the relatively chaotic years of urban growth and experimentation between 1870 and about 1910, the most casual rooming houses were built inside adapted commercial buildings. Downtown landowners often built two- to four-story loft buildings, the ground floor being an open slot of space for a store, restaurant, or saloon. If the owners wanted to lease out the upper floors as a rooming house, they built in hallways and bedrooms but in such a way that they could easily be torn out to leave a clean, simple loft space for future offices, light manufacturing, or warehousing should those uses demand higher rents in the future. Sometimes the plumbing was only on the first floor (fig. 4.4).[17] Such generic-loft structures were meant for people with the smallest rooming house incomes. Loft buildings filled their entire plot, canceling out the chance for side windows. "Dark rooms" (rooms with no direct exterior light) had windows opening into daylit corridors or into interior stair halls that had skylights over them. Some dark rooms had no windows at all.

Whatever form the old rooming house had—row house or huge recycled apartment building—the owners were often waiting to sell their

land or to lease their building at a higher price for retail or factory uses. They remodeled as little as they could. However, especially after 1900, other downtown property owners took a different tack: they built buildings with rooming houses specifically in mind.

Buildings Purposely Constructed as Rooming Houses

Living in a "used" building—one constructed for something other than multiple residences—was for tenants a bit like wearing hand-me-down clothing. The cultural fit was often less than perfect, the social appearance sometimes embarrassing and demeaning.[18] In the struggle to establish respectability, a room that was new and solely intended to be a rooming house room could be an asset for better self-respect and public status. For managers, a purpose-built structure was easier to manage than an ad hoc one. All rooms could be an equal size, with no oversized or difficult-to-rent rooms. When American landowners chose to provide permanent hotel accommodations for this price range, they did so in two different ways: small purpose-built rooming houses and huge downtown hotels.

A great many new rooming houses were built downtown after 1900 on house-sized lots but usually with an improved, specialized type of building: the downtown rooming house .[19] These buildings improved on the livability of the former-house and generic-loft buildings. The construction was not temporary; owners were confident that single-room living would bring in reliable rents for a long time. On the ground floor were store windows and commercial spaces that in their form, use, and lease income clearly said "downtown." The fifteen to forty rooms on the floors above said "residential" to those living in the structure. Relatively generous light wells illuminated and ventilated the upstairs rooms and reinforced the permanent commitment to residential use. San Francisco's Delta Hotel, built about 1910 and still in residential use in the 1990s, exemplifies the type (fig. 4.5).[20] On the street level next to the storefront is a small door, demurely marked, with a narrow interior stairway extending to the eighteen rooms on the second and third floors (fig. 4.6). Public space is at a minimum; the only lobby is a wide area in the second-floor hall near the room that serves as an office and part of the manager's unit (fig. 4.7).

Renters sometimes called their purpose-built rooming houses "upstairs hotels." The phrase is apt, since before 1910, elevators were rare

Figure 4.5

Street view of a typical small

downtown rooming house, 1992.

The former Delta Hotel in San

Francisco's South of Market district.

Figure 4.6

Entrance door to the former Delta Hotel,

San Francisco.

Figure 4.7

Plan of the second floor in

San Francisco's Delta Hotel.

A room sink is next to the

case closet in each room; the

toilet room and bathroom

are off the rear hall.

Figure 4.8

Typical rooming houses in San Francisco. Top row , from left to right:

Isabel Cory's lodgings (shaded house), built ca. 1870; the Central Pacific

Hotel, ca. 1880; the Oliver Hotel, 1906. Bottom row: National Hotel,

ca. 1906; the Salvation Army's Evangeline Residence, 1923.

in hotels of this price range. Climbing one to four flights of narrow stairs was a modal and often reluctantly faced experience for residents.[21] Stairs figured in the letters written home by Will Kortum, an eighteen-year-old lumberyard clerk from a small California town. Kortum, who moved into a new hotel of the rooming house rank on his arrival in San Francisco in early 1906, wrote this to his mother after several weeks in the city:

I received your letter last night. It is always a feeling of great pleasure when the hotel clerk in answer to your inquiry for mail, dodges behind his desk and produces an envelope. And the long stairs seem a good deal easier to climb.[22]

Later designs for large rooming houses included elevators and floor plan arrangements that were variations on the plan for the Delta. By 1930, three-fourths of San Francisco's rooming house rooms were in taller, blockier buildings of five or six stories (fig. 4.8). Lobbies and dining rooms were small (if they existed), rooms were very simple, and there were rarely more than two chairs per room. Elevator or not, at this price range, most baths remained down the hall, at a ratio of about one bath to every five or six rooms. This far exceeded the one-to-fifteen

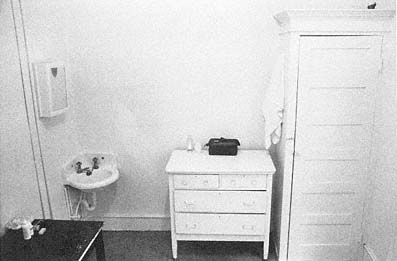

Figure 4.9

Room sink, dilapidated chest of drawers, and case closet in a large

rooming house, the National Hotel, San Francisco. In rooming houses

for men, sinks were often mounted lower than usual

and informally doubled as urinals.

ratio available in converted houses.[23] Another upward step in plumbing was a small sink in every room, typically on the same wall as a case closet—a closet built like a large cabinet or wardrobe rather than being built into the walls (fig. 4.9). The sinks, along with smuggled-in hot plates, made light housekeeping easy for tenants. For a larger rooming house, San Francisco's National Hotel is typical of the cheapest sort: no lobby, no frills, but ninety very regular rooms opening off very small light wells (fig. 4.10).

Whether found in small or large rooming houses, new or old, the conditions of one's room depended on the hotel's market and management. Matrons from the middle and upper class of San Francisco conducted a rooming house survey in 1926 and were shocked at what they saw:

There were dark rooms where it was impossible to find the washstand without first turning on electric light; dingy rooms where the carpets had a musty smell, and the furniture was shabby and faded; sleeping rooms with lumpy double beds and dirty lace curtains. . . . Most of the rooms had such dim lights that no one could read in the evening.[24]

The matrons could recommend only one-fourth of the downtown rooms they inspected. Sinclair Lewis had given a similar description in 1905, adding that the gas light "neither illuminated the mirror nor enabled the guest to read in bed."[25]

Figure 4.10

Floor plan of a large rooming house. The second floor of the National Hotel in San Francisco, built

ca. 1906. The location of the street entry is marked by a black triangle; the first room at the head

of the stairs is the office; toilets and baths are off the left rear hall. Shaded areas are light wells.

In a rooming house, one's room was never really isolated. Even for the very shy, life was indirectly social. After the third or fourth day, astute desk clerks would greet tenants by name. After two or three weeks, residents realized that they had begun to smell a bit like their hotel. At night, when the street noise died down, residents involuntarily monitored the activities and conversations in all the adjoining rooms. Coughing was a communal act; one always knew when one's neighbors had a cold. Carrying the sounds were light wells, floors, and walls built with minimal sound-deadening details; in hot weather or when the heating system overdid, hall doors and open transoms also carried sound. Personal affairs such as fights between couples could not necessarily be conducted privately behind closed doors.[26] For a guarantee of behavior better matching middle and upper class norms, some residents looked to rooming houses with more overt management.

YMCAs and other Organization Boardinghouses

As rooming houses and their residents proliferated downtown, religious and other philanthropic leaders worked to bring back old-fashioned boardinghouses at a larger scale and with more centralized administration. Providing vigilant supervision of the tenants and offering some sort of group parlor life (while at the same time prohibiting card playing and drinking) were seen by reformers—overwhelmingly Protestants—as minimal replacements for the safeguards and respectability of a private family house. Thousands of downtown residents seemingly agreed with these social and architectural guarantees of respectability (at least for short periods) as organization boardinghouses were built in great numbers and were almost always full.

The Young Men's Christian Association and the Young Women's Christian Association, transplanted from England to the United States

in 1851 and 1866, respectively, pioneered in providing inexpensive, morally conservative homes for city residents who otherwise might have lived in a rooming house.[27] Historically, because of their sharp disadvantage in salaries, women relied more on institutionally subsidized rooms than did men. Although the founders of women's boarding institutions stereotyped women living apart from families as helpless and incapable of managing their own lives, both men and women knew the advantages of Ys and other subsidized rooming houses: they were generally clean, dependable, respectable, and cheap. The combined room and food costs were often less than just the price of a room at a commercial rooming house.[28]

Especially between 1890 and 1915, other charitable boardinghouse organizations joined the movement. These homes were often sponsored according to ethnicity, race, or religion, since not all Ys accepted everyone. In 1915, New York City had fifty-four organized, nonprofit lodgings for women; Chicago had thirty-four, not counting homes run for special groups such as immigrants or unmarried mothers. From 11 to 320 women lived in each home; managers wrote that 90 to 125 tenants constituted the optimal client group.[29] The YMCA opened its doors more widely in 1925, offering membership to Jews, Catholics, and people with no religious affiliation. Each city made its own rules regarding integration of black and white members; through World War II, the YMCA typically built separate facilities for blacks and Asians. More fully integrated chapters became more common in the 1940s and particularly after the beginning of national desegregation in 1954. In some chapters, blacks could stay as transient guests but not as permanent residents.[30]

Ys and other organization boardinghouses often occupied America's most specialized boardinghouse buildings. The eight-story, 211-room Evangeline Residence built by the Salvation Army in San Francisco opened in 1923 on a site just a block from the new Civic Center. The T-shaped plan imitated the best middle-income apartment buildings and hotels. The Evangeline, however, had very small rooms, no private baths, and very plain and economical interior construction. Its managers compensated for these with a sun deck on the roof and several social spaces in addition to the lobby, dining room, and reading room.

The managers of nonprofit lodgings often imposed curfews, lectured the tenants on morals, tightly enforced house rules, and required tenants to pay for meals whether they ate them or not. Together with the

general air of charity and institutionality, these rules repulsed many people looking for long-term homes. The Ys became known as places for men and women to live only while looking for work.[31] Hearing the complaints, commercial entrepreneurs ventured successfully into the same market. The large Allerton Houses in several cities were physically very much like YMCAs and YWCAs. By 1915, Chicago had six Eleanor Clubs, a chain of commercial and self-supporting women's clubs with 60 to 150 residents each. This competition convinced the subsidized homes to reduce their restrictions.[32]

For many people, rooming houses were acceptable because of their similarities with college dormitories, fraternities and sororities, retirement homes of fraternal, ethnic, and benevolent societies (such as the Oddfellows' retirement homes), and orphanages, together with the monasteries and convents of religious orders. Institutions like these have been and still are providers of thousands of subsidized housing units in every large American city.[33]