Chapter Four—

Rooming Houses and the Margins of Respectability

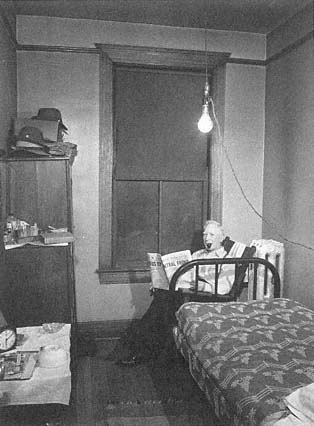

At the turn of the century, an eighteen-year-old woman named Dorothy Richardson left western Pennsylvania and moved to New York. She had meager cash reserves but was determined to find city work and a new life. "A waif and a stray, unskilled, friendless, almost penniless," she wrote of herself on her first day in the city. She found lodging in a rooming house late in the evening and woke to find rain pouring down on the skylight of the dreary, windowless little room that she hoped she could afford while she looked for employment.[1] Richardson's story typified the situation of many rooming house residents (fig. 4.1).

A century earlier and in much smaller cities, young male workers would have left their families and learned a trade while being apprenticed to a master, often living under the master's roof. However, the nature of the new industrial economy and its call for greater numbers of unskilled and lower-paid workers had undermined and overwhelmed the old apprenticeship system and loosened the direct residence ties between employers and workers. With the lure of new jobs downtown, women like Richardson were also breaking free from traditional household bonds. By 1923, one out of five employed young women in America lived away from a family home.[2] While the people who lived in palace and midpriced hotels did so largely as a matter of choice,

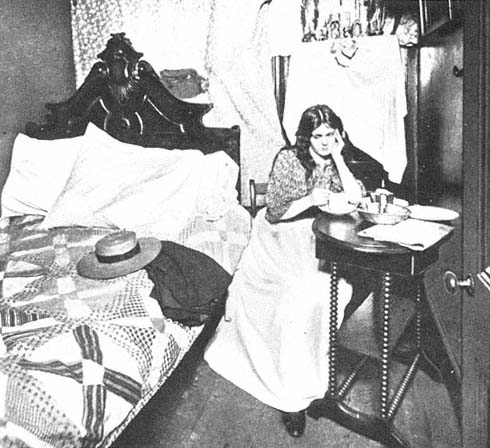

Figure 4.1

A working girl eats breakfast by candlelight in her small room, New York City, 1890s.

Behind her bed, old bedspreads conceal her clothes, probably hung on nails along

the wall because the room had no closet.

people of lesser means found hotel housing one of their few options for living downtown, particularly if they wished to live outside of a family.

Single people living alone caused concern in some circles. In 1907, the social worker Robert Woods wrote of the "social danger of a great population made up of detached men and women" living apart from the "safeguards of a good home." As late as 1949, a sociologist described a Los Angeles rooming house district as a "universe of anonymous transients."[3] Indeed, in their home life, rooming house residents belonged neither to the middle and upper class nor to the working class; the domestic rules of both classes were largely based on family life and group households. Critics felt that rooming house residents were potentially eligible for membership in polite society but constantly in danger of losing that eligibility. Rooming house residents, too, knew they were on a social edge, but to them it was often a leading edge, one moving toward more independence. As new work roles within the large

industrial city threw individuals into a social and cultural limbo, the rooming house and its surrounding district helped them balance their marginal state of affairs.

Plain Rooms

The precedents for commercial rooming houses were old-fashioned boardinghouses. Especially before the 1920s, the lines were hazy between a private family house and a commercial rooming house because so many people boarded or lodged with private families. Boarders slept in the house and also took their meals with a family; lodgers slept in the house but took their meals elsewhere. Entire families boarded—often parents or single mothers in their late twenties—but the most common boarders were young unmarried men or women with slim financial resources. Boarding and lodging so pervaded American family life (along with the presence of servants and live-in relatives) that throughout the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, use of the term "single-family house" is misleading. In a conservative estimate for those years, one-third to one-half of all urban Americans either boarded or took boarders at some time in their lives.[4]

Most private families took in one or two boarders at a time. Where more income was needed, a private boardinghouse could have six to ten tenants. Keeping a low profile helped the family avoid the technically required hotel licenses and annual taxes. In such a place, the landlady operated as surrogate mother and father. She wielded authority over parlor life and over curfews and guests. If the old house was a good structure in a decent neighborhood, the residence could be respectable for middle-income families.[5] After 1900, many people looked back nostalgically to these enterprises in comparison to their commercial counterparts.

Former-house Rooming Houses

The commercial rooming house of 1910 was run overtly and officially as an inexpensive hotel. Its manager often paid for a commercial license. The business was in a twenty-five-to forty-year-old house, three or four stories high, originally built for a middle-income family. The owners had moved to the edge of town and leased their downtown house to someone—inevitably a woman—who rented rooms as her chief source of income. The landlady of a commer-

cial rooming house often advertised in her front window with a card reading ROOM TO RENT or FURNISHED ROOMS.[6] Like Richardson, rooming house residents often began their first solo encounter with downtown life as they lugged their suitcases down the streets in rooming house districts and searched for window cards.

Figure 4.2

Second-floor plan for a conjectural

conversion of a large single-family

row house into a rooming house.

Shaded areas indicate where thin

walls have been added to cut up

the large rooms of this 1840s house.

The warren of five rooms at the front

was constructed from the two former

principal bedrooms and their closets.

The typical rooming house had earlier been a boardinghouse. After the Civil War, the number of commercial boardinghouses sharply declined. In 1875 in San Francisco, for instance, boardinghouses made up almost 40 percent of the commercial housing listings in the city directory. By 1900, boardinghouses had dwindled to fewer than 10 percent, and by 1910, they constituted less than 1 percent of those listings. Boston and Chicago saw similar declines.[7] During these declines, boardinghouse keepers were not quitting but getting out of food provision—shifting their businesses from boardinghouses to rooming houses. This shift considerably eased the landlady's life. She could rent out her dining room and parlor as additional bedrooms; she could fire the one or two servants she had needed to provide the meals. Eliminating meal service eliminated the most troublesome and costly parts of her business.[8] In a rooming house, the residents ate their meals with a family down the street or (as was most often the case) in commercial eateries.

Architecturally, the former-house rooming house was usually a fairly large row house with from sixteen to eighteen rooms, including the bath, the laundry, and the landlady's kitchen, if there was one (fig. 4.2). Owners or landladies created extra rooms by subdividing larger bedrooms and parlors and providing approaches to them with dark deadend hallways. Like the attic room that Richardson found in her first week in New York, some rooms had only a transom window onto a hallway, a tiny dark air shaft, or a nonopening skylight. Until after World War I, few of these rooming houses offered central heating; small individual stoves or coal grates served to heat the rooms.[9] The high rents of undivided parlors and dining rooms required two residents to pay for them. The lowest-priced rooms were on the upper floors, with unheated attic and end-of-hallway rooms costing the least. On occasion, owners joined several houses together, creating a single rooming house with as many as forty rooms and seventy tenants.[10]

Chairs—their number, repair, and plushness—indicated any hotel room's social rank. In a good midpriced hotel, three chairs were the minimum; in rooming houses, two were the maximum. At the second

of Richardson's many rooming houses, she listed the furniture in her room: a battered but cheering "tiny mite of a stove," an equally battered wooden bedstead that creaked and groaned at her every move on its thin mattress, a single chair with a mended leg, an evil-smelling lamp with a wick not quite long enough, and a tremulous kitchen table. She longed for simple comforts of more expensive quarters, complaining that there was "no bureau, only a waved bit of looking-glass over the sink in the corner. My wardrobe was strung along the row of nails behind the door."[11] Beneath the row of nails and her few pieces of clothing Richardson stored a wooden trunk, her only piece of luggage.

Most former-house rooming houses offered only the one bathroom built for the original family, whether the house had nine bedrooms or eighteen, six tenants or twenty. Usually the bathroom was on the second floor. To conserve the high cost of fuel, landladies tacked up signs that sternly limited residents to no more than one hot bath per week. The customary plan was to supply hot water once or twice a week, although during the summer, hot water could be unavailable for months at a time. Towels were often in short supply. Residents facing a week without hot water could resort to large public or commercial bathhouses where hot baths cost 10 or 15 cents in 1900. Tenants lucky enough to have a room with a washstand, a pitcher, and a bowl—a pitcher and bowl that were "inevitably cracked"—carried the water themselves.[12]

From one city to another, names and conditions in old-house rooming houses showed only minor variations, one of which was what people called the buildings. In Philadelphia, the common term was furnished-room house; in New York, Chicago, Cleveland, and St. Louis, rooming house; in Boston and San Francisco, lodging house .[13] Since blacks were excluded as guests in most hotels and rooming houses, in many cities, black rooming houses and boardinghouses had a greater mixture of transient and permanent guests than did rooming houses run for whites. Other special cases of converted buildings were converted apartments. Especially after the depression and World War II, entrepreneurs would lease old, eight-room to ten-room apartments and then sublet the rooms individually. All the tenants would share the bath and the kitchen. An entire multistory apartment building could be converted into such single-room units.[14]

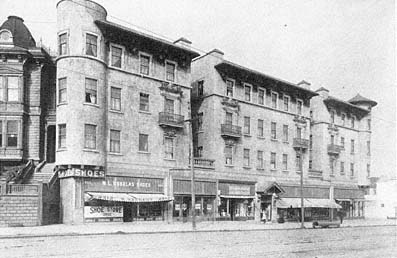

Figure 4.3

A Victorian era booster hotel on a small town's Main Street and public square, 1940. By the time of

the photograph, the clients of this Rockville, Indiana, hotel were likely paying rooming house rents.

Building owners also made rooming houses out of run-down palace or midpriced hotels. They eliminated service, repairs, and amenities until the rents matched rooming house levels (fig. 4.3). For example, San Francisco's Central Pacific Hotel was originally built as a midpriced hotel. By the 1880s and 1890s, it commanded only rooming house prices and was home to a wide range of residents. In 1880, behind the five ground-floor shops lived the shopkeepers and their families, 21 people in all. Also on the ground floor were the hotel dining room and lobby. Upstairs were transient guests, along with 42 permanent residents. Fifteen of the permanent residents were the hotel owners, the two servants, and their three families. Of the remaining 27 permanent lodgers, 26 were single adult males, overwhelmingly Irish (as were the owners of the hotel, the Farrells). The lodgers were mostly twenty-five to thirty-five years old, although the range was from a fifteen-year-old blacksmith to a sixty-three-year-old laborer. The depression of the late 1870s had hit these men hard; the average tenant at the Central Pacific Hotel had been out of work for over seven months in 1879–80.[15] Large hotels like the Central Pacific had the advantage of a night clerk, which eliminated the small rooming house's curfew. Instead of the landlady

Figure 4.4

A generic-loft rooming house, built about 1880. The Frye

Rooming House near Chinatown in San Francisco was

adjacent to a cigar factory. The upper floors, with 16 rooms,

could easily be converted to other uses. The fenestration is

conjectural.

locking the front door at ten or eleven at night, the doors of a large hotel were open around the clock. Late tenants did not have to rouse an angry or inquisitive manager.[16]

In the relatively chaotic years of urban growth and experimentation between 1870 and about 1910, the most casual rooming houses were built inside adapted commercial buildings. Downtown landowners often built two- to four-story loft buildings, the ground floor being an open slot of space for a store, restaurant, or saloon. If the owners wanted to lease out the upper floors as a rooming house, they built in hallways and bedrooms but in such a way that they could easily be torn out to leave a clean, simple loft space for future offices, light manufacturing, or warehousing should those uses demand higher rents in the future. Sometimes the plumbing was only on the first floor (fig. 4.4).[17] Such generic-loft structures were meant for people with the smallest rooming house incomes. Loft buildings filled their entire plot, canceling out the chance for side windows. "Dark rooms" (rooms with no direct exterior light) had windows opening into daylit corridors or into interior stair halls that had skylights over them. Some dark rooms had no windows at all.

Whatever form the old rooming house had—row house or huge recycled apartment building—the owners were often waiting to sell their

land or to lease their building at a higher price for retail or factory uses. They remodeled as little as they could. However, especially after 1900, other downtown property owners took a different tack: they built buildings with rooming houses specifically in mind.

Buildings Purposely Constructed as Rooming Houses

Living in a "used" building—one constructed for something other than multiple residences—was for tenants a bit like wearing hand-me-down clothing. The cultural fit was often less than perfect, the social appearance sometimes embarrassing and demeaning.[18] In the struggle to establish respectability, a room that was new and solely intended to be a rooming house room could be an asset for better self-respect and public status. For managers, a purpose-built structure was easier to manage than an ad hoc one. All rooms could be an equal size, with no oversized or difficult-to-rent rooms. When American landowners chose to provide permanent hotel accommodations for this price range, they did so in two different ways: small purpose-built rooming houses and huge downtown hotels.

A great many new rooming houses were built downtown after 1900 on house-sized lots but usually with an improved, specialized type of building: the downtown rooming house .[19] These buildings improved on the livability of the former-house and generic-loft buildings. The construction was not temporary; owners were confident that single-room living would bring in reliable rents for a long time. On the ground floor were store windows and commercial spaces that in their form, use, and lease income clearly said "downtown." The fifteen to forty rooms on the floors above said "residential" to those living in the structure. Relatively generous light wells illuminated and ventilated the upstairs rooms and reinforced the permanent commitment to residential use. San Francisco's Delta Hotel, built about 1910 and still in residential use in the 1990s, exemplifies the type (fig. 4.5).[20] On the street level next to the storefront is a small door, demurely marked, with a narrow interior stairway extending to the eighteen rooms on the second and third floors (fig. 4.6). Public space is at a minimum; the only lobby is a wide area in the second-floor hall near the room that serves as an office and part of the manager's unit (fig. 4.7).

Renters sometimes called their purpose-built rooming houses "upstairs hotels." The phrase is apt, since before 1910, elevators were rare

Figure 4.5

Street view of a typical small

downtown rooming house, 1992.

The former Delta Hotel in San

Francisco's South of Market district.

Figure 4.6

Entrance door to the former Delta Hotel,

San Francisco.

Figure 4.7

Plan of the second floor in

San Francisco's Delta Hotel.

A room sink is next to the

case closet in each room; the

toilet room and bathroom

are off the rear hall.

Figure 4.8

Typical rooming houses in San Francisco. Top row , from left to right:

Isabel Cory's lodgings (shaded house), built ca. 1870; the Central Pacific

Hotel, ca. 1880; the Oliver Hotel, 1906. Bottom row: National Hotel,

ca. 1906; the Salvation Army's Evangeline Residence, 1923.

in hotels of this price range. Climbing one to four flights of narrow stairs was a modal and often reluctantly faced experience for residents.[21] Stairs figured in the letters written home by Will Kortum, an eighteen-year-old lumberyard clerk from a small California town. Kortum, who moved into a new hotel of the rooming house rank on his arrival in San Francisco in early 1906, wrote this to his mother after several weeks in the city:

I received your letter last night. It is always a feeling of great pleasure when the hotel clerk in answer to your inquiry for mail, dodges behind his desk and produces an envelope. And the long stairs seem a good deal easier to climb.[22]

Later designs for large rooming houses included elevators and floor plan arrangements that were variations on the plan for the Delta. By 1930, three-fourths of San Francisco's rooming house rooms were in taller, blockier buildings of five or six stories (fig. 4.8). Lobbies and dining rooms were small (if they existed), rooms were very simple, and there were rarely more than two chairs per room. Elevator or not, at this price range, most baths remained down the hall, at a ratio of about one bath to every five or six rooms. This far exceeded the one-to-fifteen

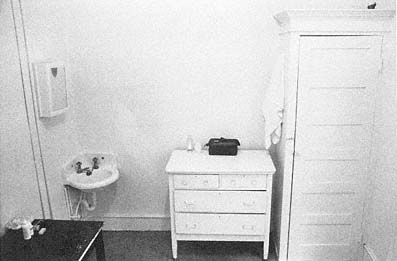

Figure 4.9

Room sink, dilapidated chest of drawers, and case closet in a large

rooming house, the National Hotel, San Francisco. In rooming houses

for men, sinks were often mounted lower than usual

and informally doubled as urinals.

ratio available in converted houses.[23] Another upward step in plumbing was a small sink in every room, typically on the same wall as a case closet—a closet built like a large cabinet or wardrobe rather than being built into the walls (fig. 4.9). The sinks, along with smuggled-in hot plates, made light housekeeping easy for tenants. For a larger rooming house, San Francisco's National Hotel is typical of the cheapest sort: no lobby, no frills, but ninety very regular rooms opening off very small light wells (fig. 4.10).

Whether found in small or large rooming houses, new or old, the conditions of one's room depended on the hotel's market and management. Matrons from the middle and upper class of San Francisco conducted a rooming house survey in 1926 and were shocked at what they saw:

There were dark rooms where it was impossible to find the washstand without first turning on electric light; dingy rooms where the carpets had a musty smell, and the furniture was shabby and faded; sleeping rooms with lumpy double beds and dirty lace curtains. . . . Most of the rooms had such dim lights that no one could read in the evening.[24]

The matrons could recommend only one-fourth of the downtown rooms they inspected. Sinclair Lewis had given a similar description in 1905, adding that the gas light "neither illuminated the mirror nor enabled the guest to read in bed."[25]

Figure 4.10

Floor plan of a large rooming house. The second floor of the National Hotel in San Francisco, built

ca. 1906. The location of the street entry is marked by a black triangle; the first room at the head

of the stairs is the office; toilets and baths are off the left rear hall. Shaded areas are light wells.

In a rooming house, one's room was never really isolated. Even for the very shy, life was indirectly social. After the third or fourth day, astute desk clerks would greet tenants by name. After two or three weeks, residents realized that they had begun to smell a bit like their hotel. At night, when the street noise died down, residents involuntarily monitored the activities and conversations in all the adjoining rooms. Coughing was a communal act; one always knew when one's neighbors had a cold. Carrying the sounds were light wells, floors, and walls built with minimal sound-deadening details; in hot weather or when the heating system overdid, hall doors and open transoms also carried sound. Personal affairs such as fights between couples could not necessarily be conducted privately behind closed doors.[26] For a guarantee of behavior better matching middle and upper class norms, some residents looked to rooming houses with more overt management.

YMCAs and other Organization Boardinghouses

As rooming houses and their residents proliferated downtown, religious and other philanthropic leaders worked to bring back old-fashioned boardinghouses at a larger scale and with more centralized administration. Providing vigilant supervision of the tenants and offering some sort of group parlor life (while at the same time prohibiting card playing and drinking) were seen by reformers—overwhelmingly Protestants—as minimal replacements for the safeguards and respectability of a private family house. Thousands of downtown residents seemingly agreed with these social and architectural guarantees of respectability (at least for short periods) as organization boardinghouses were built in great numbers and were almost always full.

The Young Men's Christian Association and the Young Women's Christian Association, transplanted from England to the United States

in 1851 and 1866, respectively, pioneered in providing inexpensive, morally conservative homes for city residents who otherwise might have lived in a rooming house.[27] Historically, because of their sharp disadvantage in salaries, women relied more on institutionally subsidized rooms than did men. Although the founders of women's boarding institutions stereotyped women living apart from families as helpless and incapable of managing their own lives, both men and women knew the advantages of Ys and other subsidized rooming houses: they were generally clean, dependable, respectable, and cheap. The combined room and food costs were often less than just the price of a room at a commercial rooming house.[28]

Especially between 1890 and 1915, other charitable boardinghouse organizations joined the movement. These homes were often sponsored according to ethnicity, race, or religion, since not all Ys accepted everyone. In 1915, New York City had fifty-four organized, nonprofit lodgings for women; Chicago had thirty-four, not counting homes run for special groups such as immigrants or unmarried mothers. From 11 to 320 women lived in each home; managers wrote that 90 to 125 tenants constituted the optimal client group.[29] The YMCA opened its doors more widely in 1925, offering membership to Jews, Catholics, and people with no religious affiliation. Each city made its own rules regarding integration of black and white members; through World War II, the YMCA typically built separate facilities for blacks and Asians. More fully integrated chapters became more common in the 1940s and particularly after the beginning of national desegregation in 1954. In some chapters, blacks could stay as transient guests but not as permanent residents.[30]

Ys and other organization boardinghouses often occupied America's most specialized boardinghouse buildings. The eight-story, 211-room Evangeline Residence built by the Salvation Army in San Francisco opened in 1923 on a site just a block from the new Civic Center. The T-shaped plan imitated the best middle-income apartment buildings and hotels. The Evangeline, however, had very small rooms, no private baths, and very plain and economical interior construction. Its managers compensated for these with a sun deck on the roof and several social spaces in addition to the lobby, dining room, and reading room.

The managers of nonprofit lodgings often imposed curfews, lectured the tenants on morals, tightly enforced house rules, and required tenants to pay for meals whether they ate them or not. Together with the

general air of charity and institutionality, these rules repulsed many people looking for long-term homes. The Ys became known as places for men and women to live only while looking for work.[31] Hearing the complaints, commercial entrepreneurs ventured successfully into the same market. The large Allerton Houses in several cities were physically very much like YMCAs and YWCAs. By 1915, Chicago had six Eleanor Clubs, a chain of commercial and self-supporting women's clubs with 60 to 150 residents each. This competition convinced the subsidized homes to reduce their restrictions.[32]

For many people, rooming houses were acceptable because of their similarities with college dormitories, fraternities and sororities, retirement homes of fraternal, ethnic, and benevolent societies (such as the Oddfellows' retirement homes), and orphanages, together with the monasteries and convents of religious orders. Institutions like these have been and still are providers of thousands of subsidized housing units in every large American city.[33]

Economic Limbo

Like Dorothy Richardson, the vast majority of single-room residents in turn-of-the-century rooming houses were young men and women recently arrived in the city. In 1906, the sociologist Albert Wolfe characterized the rooming house residents of Boston's South End as a "great army of clerks, salesmen, bookkeepers, shop girls, stenographers, dressmakers, milliners, barbers, restaurant-keepers, black railroad porters and stewards, policemen, nurses, . . . journeymen carpenters, painters, machinists, and electricians" (fig. 4.11).[34] In more clinical terms, Wolfe had found an army of low-paid but skilled white-collar and blue-collar workers, rarely immigrants but usually American-born of northern European and most often Protestant stock.

These city recruits struggled with their uncertain standing: they often held strong family values but were living outside a family; they were capable of being well dressed but only in one or two outfits; they aspired to material comfort but had access to very little of it; they aimed for economic security but lived with uncertain incomes. Typically, work had lured rooming house residents to the city, and it was the realities of their work that kept them in an economic and residential limbo.

Figure 4.11

Course in typing and Dictaphone, 1906, at Bryant High School, New York City. Young people

trained in these skills were often rooming house residents.

Rooming house women and men shared similar employments but had sharply differing incomes. The women's situation was the more acute. Women represented a third to a half of the people in American rooming houses.[35] In Wolfe's 1906 study, about one-sixth of the women were wives with no employment outside their homes. Single elderly women, or as Wolfe put it, "old ladies, most of them living on modest incomes, or supported by some relative or by charity," made up 8 percent of the women in his study. Stenographers, waitresses, dressmakers, saleswomen, and clerks roughly tied as the most common occupations among the working women, with 6 to 8 percent apiece.[36] The waitresses typically worked in small cafés within the rooming house district itself. The clerks worked in small shops, not in department stores where wages were too low to support even the cheapest rooming house rents. In San Francisco, women's average pay in similar jobs in 1920 was still typically too low for women to live alone in a rooming house as men did (table 3, Appendix). Thirty to 60 percent of San Francisco's working women could not afford a room alone, espe-

cially before 1920, and they doubled up with another woman to share the rent. The only lower pay rates in San Francisco were those of Chinese laborers and children.[37]

After 1920, new industrial and commercial jobs and the sudden rise of entry-level white-collar work helped more women migrate to the city and live outside a family. The U.S. Census showed an increase from 1,300 San Francisco stenographers and typists in 1900 to nearly 12,000 in 1930. In those same years, women's jobs as bookkeepers, cashiers, and accountants increased by a factor of six. The number of women working in more traditional retail clerk jobs doubled between 1900 and 1910 and again by 1920. Nationally, women were half of the total office force by 1920; clerical work made up a quarter of women's jobs and had surpassed manufacturing as the second largest employer of women.[38] These surges in women's office work were closely related to factory and wholesaling expansions. From 1890 to 1920, each two additional unskilled industrial workers added a new salaried overseer or skilled office worker.[39] These women, when they were single, increasingly looked to rooming houses for shelter.

Among the men in Wolfe's study, "clerk" and "salesmen" were the most common occupations, with 13 and 8 percent, respectively. Merchants and waiters were equal, with about 5 percent; the other significant groups were foremen, engineers, real estate and insurance workers, and cooks.[40]

Skilled workers did not figure prominently in Wolfe's study of Boston, but in many cities skilled workers were common in rooming houses (fig. 4.12). In San Francisco, for instance, a fourth of the city's carpenters in 1900 were boarders or lodgers, most of them living downtown. Students in colleges and business schools relied on rooming houses. Woodrow Wilson lived in Baltimore rooming houses in 1883 – 84 while he was a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University. After World War II, the employment of rooming house men shifted with the urban economy. In New York, people working in the merchant marine or night bus routes became as common as waiters had been before the war.[41]

For both men and women in rooming houses, frequent moves were common. Half the roomers in a city moved within a typical year, usually from one rooming house to another. Frequent moves were also part of the work life for machinists, cigar workers, and people in construction trades. Layoffs were another major factor in this rooming house

Figure 4.12

A 68-year-old railroad employee in his YMCA room in Gibson,

Indiana, 1943.

mobility. Jobs at this income level were often erratic or seasonal. Particularly in the slow summer months, roomers were forced to desert the city and live elsewhere—often with their rural families. Frequent moves were easily accomplished because roomers owned few personal possessions and could pack them into one or two bags or at most a trunk. Two rooming house women joked that the word home for them meant "a place where we can unpack our trunk, anchor our electric iron and hang our other blouse over the chair."[42]

Although the number of roomers increased from 1870 to 1950, and their employment changed, the sex and age composition of rooming house areas remained relatively constant. Ages between twenty and forty-five were far more represented than in immigrant family neighborhoods or in the suburbs. Rooming house people rarely had children living with them, although social workers' interests in children meant that reports usually overemphasized them. The elderly men and women in rooming houses, although not generally prominent before World

War II, tended to live in the older and cheaper buildings. In the late 1920s, one committee reported that lack of proper heat was "one of the great privations of the elderly" in single-room housing.[43] Landladies said that they preferred men to women as tenants because men were more easygoing and long-suffering—and out of the house more. Women were "constantly waiting to use the laundry, wash in their rooms, or do light cooking." Men could also afford higher rents. From their side, women complained that the landladies required women tenants to do their own cleaning, while for the same rents, the men did not.[44]

Nineteenth-century rooming house residents also sorted themselves by ethnic, racial, and occupational considerations. Some housekeepers preferred Catholic or Protestant tenants, or mechanics over clerks. These distinctions became less common after 1900. When blacks moved into Chicago rooming house areas, the population pyramids and age-sex formations did not change, although racial discrimination meant that crowding was far worse inside black rooming houses.[45]

Not everyone in rooming houses was single or living alone. Couples, either married or unmarried, ranged from 7 to 38 percent of the roomers. White couples often rented two-room suites. Crowded conditions in black rooming houses largely precluded more than one room. After World War II, some rooming house districts had a higher proportion of couples (again, both married and unmarried) than those neighborhoods had seen in the 1920s. The life-style remained similar to the earlier period. For women, becoming a "charity girl" (that is, living with a man without marrying him) became one way to escape the binds of low wages. Being a charity girl was at least an alternative to working in the sexual service sector: prostitution, taxi-dance work, dancing in a chorus line, gold digging (that is, consorting with men primarily for expensive gifts or lucrative divorces), or in later years, cocktail waitressing.[46] Nominally appearing to be single, homosexual couples of men or women could also live together in rooming houses. They apparently provoked little suspicion or approbation, as adult pairs of men or women commonly lived together to share expenses. Some rooming house districts were known to be areas that gay men or lesbians lived in and frequented.[47]

Rooming houses also proved useful for families with a problem relative. Families could rid themselves of offending relatives by sending

them to a distant city and supporting them with steady monthly payments as long as they stayed away. From wealthy families, such a remittance man or remittance woman could derive a comfortable life in a palace or midpriced hotel. For the vast majority, however, this situation meant a rooming house. Each remittance person had his or her reasons for being sent away; the common problems were drink, gambling, congenital brain defects, eccentricity, or being mildly crazy. "Every hotel has its crank boarders," hotel manager Ford told his peers at a convention speech in 1903. He continued with this example:

One of the good old New York hotels had a lady who stole a plate at every meal and kept them all in her room—for 30 years. She's not quite right in her mind, but she's unexceptional in regard to everything except plates.[48]

In surveys taken in the 1920s, college students complained that rooming house and residence club life forced them to associate with people who displayed personal peculiarities and maladjustment or who were "mentally or nervously upset."[49] The cheaper the hotel, the more likely would residents find this admixture to the population.

Low entry costs coupled with low and uncertain pay brought most people to the front desk of a rooming house. Unlike setting up an apartment, rooming house tenants did not have to buy linens, dishes, furniture, or cleaning equipment. In 1906, for their ready-to-live-in room, tenants paid from $1 to $7 a week (or its multiple by the month). Young Will Kortum in San Francisco found that the cheapest livable hotel rooms in the South of Market district were dark hall rooms at $2 a week or rooms with outside light for $2.50 a week. In Boston's South End, he would have found similar prices. The large rooms in an old house cost from $4.50 to $6.[50] After two decades of inflation, 1920s prices in former-house rooming houses had not gone up, while tenants in newer, purpose-built rooming houses paid from $4 to $10. The average rooming house tenants paid about the same per week for food as they did for rent.[51] Against these weekly costs, a woman salesclerk or sewing machine operator in San Francisco earned only $9 to $12 a week in 1910; unskilled confectionary workers or biscuit packers made only $6 to $9. Men operating sewing machines made $18 to $21, and other skilled men's incomes went to about $25 a week (table 4, Appendix).[52] The low prices in rooming houses kept an independent low-paid work force available to downtown industries and also helped young

single Americans forge personal independence and a subculture separate from the city's family zones. The rooming house district became notable for both of these roles.

Rooming House Districts:

Diversity and Mixture

In addition to many rooms at low prices, rooming house residents needed at least two other features: easy access to work places, and a surrounding neighborhood with mixed land use including stores, bars, restaurants, and clubs for association with friends and commercial recreation. Few outsiders questioned the first of these two needs. However, the retail mixtures of rooming house neighborhoods caused concern within the dominant culture. They also reinforced the liminal status of rooming house residents.

The Mixtures of Rooming House Streets

Work places and rooming houses were inextricably linked. Especially during boom times, employers needed a ready supply of help on short notice, and workers could afford only so much time and money for their journey to work. Given the erratic availability of employment, they also needed to be within easy reach of many different companies. Roomers rarely owned cars. Thus, rooming house areas were usually within half a mile of varied jobs. For the greatest number of rooming house residents, work was downtown in the retail shopping district in the office core, or in a warehouse, shipping, or manufacturing zone very close to the center of the city. Higher-paid white-collar workers could afford to commute on streetcars to an outlying rooming house area (fig. 4.13). Streetcar transfer locations like these were exceptions to the dominant pattern, but made up between 5 and 10 percent of San Francisco's rooming house supply by 1930.[53]

Rooming houses might have seemed unnecessary to downtown, but they were just as essential for urban economic growth as the family tenements that stretched next to factories and just as basic as the new downtown skyscrapers and loft buildings. At the turn of the century, urban Americans knew at least two different types of rooming house areas: districts of old-house rooming houses, and newer purpose-built rooming house districts.

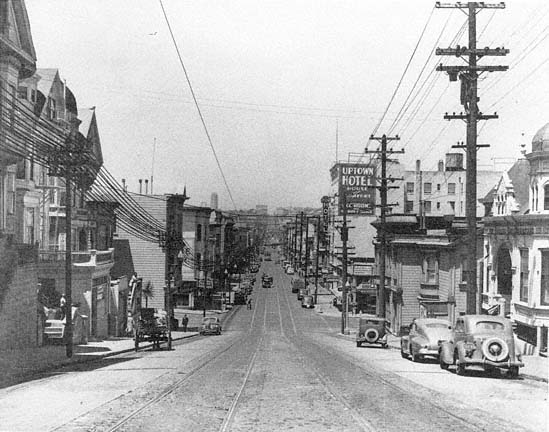

Figure 4.13

A large outlying rooming house in San Francisco, photographed ca. 1912.

Streetcars to downtown ran directly past the building. Note entrance to hotel

under the small gable roof in the center of the storefronts.

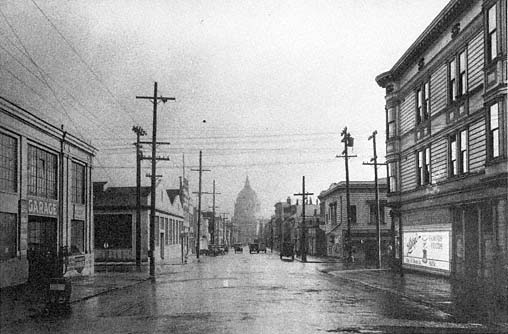

A large central area of San Francisco known as the Western Addition was a quintessential old-house rooming district. Fillmore Street was its commercial and entertainment spine (fig. 4.14).[54] The Western Addition was a twenty-minute walk west of downtown. Between downtown and the Western Addition was a neighborhood of newer flats and houses with higher rents, an area rebuilt after the fire of 1906. Several major streetcar lines crossed the Western Addition on their way farther west to single-family neighborhoods. By the 1920s, Fillmore Street's vaudeville houses, dance halls, and inexpensive restaurants were well known in San Francisco. After the fire, many downtown entrepreneurs had relocated along the street. From the public experience of this main artery, the whole Western Addition was most commonly known as "the Fillmore," although the street itself was off-center, near the edge of the neighborhood (fig. 4.15). Most of the area was filled with former middle-income houses and flats, most built in wood between 1870 and 1900, the later ones using wildly exuberant Victorian ornamentation. Commercial land-use mixture in the Western Addition was common. Owners had built long rows of storefronts into the base of houses or flats and leased them to corner grocery stores, tobacconists, bars, millinery shops, secondhand stores, and antique shops. On the side streets were auto dealers, repair shops, and commercial laundries that stood next to housing and were important employers in the neighborhood (fig. 4.16). Along the major avenues were other employers. At the southeastern corner of the district, the postfire city hall and civic center office complex offered nearby white-collar employment.[55]

Figure 4.14

Map of two principal rooming house districts in

San Francisco. Streets running north and south

(vertically) are, from left to right, Divisadero,

Fillmore, and Van Ness. The diagonal is Market Street.

Figure 4.15

Residential section of Fillmore Street in 1944. Seen looking north from Grove Street, this view was

typical of the southern edge of the Western Addition.

Figure 4.16

Side street in the Western Addition in the 1920s. Laundries and industrial shops mixed with

older flats, many rented as rooming houses.

To people from the newer, richer family districts of San Francisco, the streets of the Western Addition epitomized mixture, crude commercialism, and unskilled employment. Many of the commercial building fronts were jerry-built. The housing and commercial spaces were built of wood and rarely faced with masonry, as were the areas closer to downtown. The district represented reuse, the filtering of blocks to new tenants. In the late 1950s, when Alfred Hitchcock looked for an old rooming house setting for a mysterious transitional character in Vertigo , he found what he needed on the southern edge of the Western Addition.[56]

The Western Addition was also known for its social, ethnic, and racial diversity. After the fire, inexpensive rooms of the Western Addition became home for a growing number of German, Russian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants, along with more consolidated settlement patterns of Japanese and African-American families who had been living in dispersed patterns before the fire.[57] At the end of the depression, San Francisco's Real Property Survey documented race on a unit-by-unit basis, showing that at the eastern edge of the Western Addition African-American families were mixed with Japanese, Filipino, and European families. The 1940 census showed that the city's 5,000 blacks

Figure 4.17

Ellis Street in the Tenderloin district, San Francisco, in the early 1940s. Buildings of one-room and

two-room apartments are interspersed next to tall residential hotels.

made up less than 1 percent of the city's population; in the Western Addition, African-Americans comprised 5 percent and by 1960 would comprise half the residents in the area.[58] Most cities had a zone of converted houses with a succession similar to the Western Addition. In Boston, it was the South End; in New York, Chelsea came to be a zone of converted houses; in Chicago, it was the Near North Side.

An adjacent San Francisco area, the Tenderloin district, exemplified another type of rooming precinct—a rebuilt rooming house area that was overwhelmingly white as late as 1970.[59] The Tenderloin is essentially bounded on the west by the Western Addition and on the north by Nob Hill, and it is immediately west of the department stores around Union Square. By the 1920s, most cities had two or three such areas, some of them only a few blocks in extent. Such areas were not composed of old converted houses but new urbane buildings expressly intended as rooming houses, often next to middle-income apartments and midpriced hotels (fig. 4.17). If a single 100-room hotel had represented the social stratification of the hotels in the Tenderloin in 1930, 52 of the rooms would have been of the rooming house type; 26, midpriced; and 22, the cheap lodging house type. The Tenderloin typified a rebuilt rooming house area also in that along one side (the Nob Hill

Figure 4.18

The bright light district on Fillmore Street in the 1920s. After the fire of 1906, Fillmore became one of the

substitutes for the burned Market Street. The corner light fixtures added a festival air to the street year-round.

side), it had expensive apartments and houses; and on the opposite side (the South of Market) was a huge district of working-class housing. The newness of the Tenderloin in the 1920s was a result of the rebuilding required after San Francisco's 1906 fire. Even without such a stimulus, however, landowners in other cities had found the same rebuilding necessary and profitable. In 1930, the Tenderloin had 59 percent of San Francisco's rooming house units. All of the new rooming house districts, together, had a third of the city's residential hotel rooms.[60]

For roomers in any type of rooming house district, a short journey to play was as important as a short journey to work. Rooming house areas relied on thoroughfares with heavy streetcar or bus service and commercial businesses that catered to people from throughout the city. In San Francisco, prime examples were Fillmore and Market streets. Like the thoroughfares that cut through the bright light districts of other cities, Market and Fillmore were busy at night with people going out to eat and be entertained at the theaters, vaudeville houses, movie halls, and large dance halls—the latter being prominent and often on the second floor above retail stores.[61] Inexpensive restaurants, cafeterias, bars or lounges, and variety stores filled the interstices (fig. 4.18).

Above the larger men's clothing stores were often pool halls. As one commentator put it, in such an area the clothing store signs always advertised for "gents," never for "men" or "gentlemen."[62] These bright light entertainments and retail bargains depended more on people from outside the rooming house zone than from inside it. Local residents relied more on smaller stores scattered throughout the zone: small bakeries, tailor shops, laundries, drugstores, shoe repair shops, and also (depending on the decade and local state law) corner liquor stores that also sold convenience food and snacks at exorbitant prices.[63] Nearest the workers' cottage or tenement districts were usually a few goodsized public bathhouses so essential for tenants who had hot water only once a week.[64] At the sleaziest or least expensive side of the rooming house area, but never far from the main thoroughfare, one would see astrologers' parlors, saloons, and fairly obvious houses of prostitution. No matter where one traveled in the rooming house zone, however, there were restaurants of all descriptions. Their role was central to the residents of the area.

Simple Food

On a day-to-day basis, the most important provision of the rooming house district was inexpensive food (fig. 4.19). Individualized dining was a major advantage of rooming houses over oldstyle boardinghouses. Boarders complained about eating at preset times, paying for meals whether they were there or not, not getting enough food, not having food they liked, and enduring very repetitious fare. While living in a rooming house, tenants could choose from a variety of places to eat, at varied prices, and over a much wider range of hours—provided payday was not too far away.[65]

The cheapest eateries were almost literally holes in the wall: tiny storefronts or basements, minimally adapted for their new uses. In Boston's South End in 1900, building owners converted house basements into small dining rooms managed, as Wolfe put it, by women "of uncertain experience." The atmosphere was dark, hot, and unfriendly. The beverage included with the meals could be either coffee or tea (one could not always be sure which it was, Wolfe said). However, the table d'hôte meals of four dishes cost as little as 20 cents each. Model boardinghouses run by home economists and settlement volunteers could not set a table at such low prices. At small storefront places in the industrial areas, the lunch fare was likely a cheap stew (potatoes,

Figure 4.19

Wallet card advertising a

beanery-style fast-food

emporium in New York City, 1901.

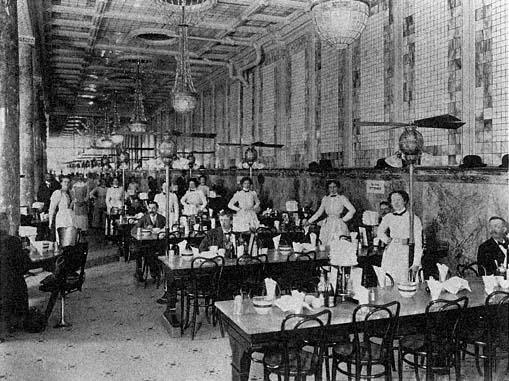

Figure 4.20

Child's Restaurant, a dairy lunchroom in New York City, ca. 1900.

carrots, and as little meat as possible) served with bread, pie, and coffee. Later, cafeterias and small counter-and-booth luncheonettes in rooming house areas continued the traditions of the small eateries. Through the 1960s, they remained a frequent haunt of rooming house residents.[66]

Larger basement restaurants offered similar bargains but better atmosphere. In the 1880s and 1890s, large and profitable places known as "three for two" restaurants catered to rooming house patrons, offering three 10-cent courses for two bits (25 cents). These eateries were a variation on the "beef and" restaurants, serving beans with a hefty cut of beef or pork, that sprang up after the Civil War.[67] Richardson, in the New York she knew during the late 1890s, occasionally treated herself with a good meal and a cup of hot coffee at a dairy lunchroom or quick lunchroom (fig. 4.20). Dairy lunchrooms were in large storefront spaces, attractively remodeled with white tile walls. They opened early and closed late. In some, tidy waitresses gave rapid service; in others, patrons picked up their food and ate at side-arm chairs. From a fairly large bill of fare, patrons could have a full dinner for 15 cents, order items à la carte for 5 to 7 cents, and efficiently pay the cashier in her cagelike desk.[68]

Meals in smaller new cafés were an even bigger treat for roomers who wanted a special dinner out. The range of Bohemian cafés in rooming house districts were typically known throughout the city for their informal dress, casual manners, and reasonable prices. Most cafés commanded a street view through plate glass windows and also had electric lights and fans. They were clean and attractive and had linen tablecloths. A steady café diet could cost $4.50 or $6 a week, as even spare breakfasts cost 20 cents; lunches, 25 cents; and dinners, 35 cents. Inexpensive hotel dining rooms essentially offered the same service (fig. 4.21).[69]

For convivial alternatives to the cafés, rooming house residents could turn to bars and saloons. Eating in a saloon was clearly working-class behavior and hence suspect for young people who aspired to the middle and upper class. Yet in 1912 a Philadelphia housing reformer defended the saloon with a positive description:

[Patrons at a saloon] could have a good dish of soup by purchasing a glass of beer for five cents. Often there is an egg, a clam, a fried oyster, or reed-bird

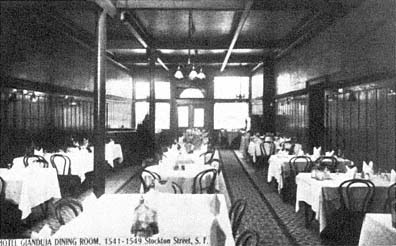

Figure 4.21

A small hotel's dining room. For rooming house residents, the Hotel Gianduja

in San Francisco's North Beach was a typical place for a special dinner.

given free with every drink. . . . For a very small price a hungry man can get as much as he cares to eat or drink. . . . As a rule the food is good, well-cooked, and palatable.[70]

Furthermore, he said, "That air of poverty which unfailingly pervades the cheap restaurants, and finds its expression in cheap and dirty table linen, is wanting in the saloon."[71] Polished oak or mission tables greeted saloon patrons (fig. 4.22). Richardson, too, was surprised one day when her fellow laundry workers whisked her through the women's entrance to a saloon. "Whatever the soup was made of, it seemed to me the best soup I had ever eaten in New York," she wrote, adding that she would "never again blame a working man or woman for dining in a saloon in preference to the more godly and respectable dairy-lunch room."[72] In the early 1900s, many saloons required that hungry patrons buy two beers to get the free lunch.

Other competitors to cheap cafés were illegal hot plates in one's room. Landladies often supplied these, to the concern of fire marshals. Regular diets of snack foods were available at the many neighborhood bakeries, delicatessens, grocery stores, and fruit stands. Their ready-to-eat bread, cake, cheese, and pickles supplemented the hot-plate fare.[73] Not only rooming house residents but also permanent guests at nearby midpriced hotels availed themselves of the delicatessen supplies.

In both the older, revamped neighborhoods like the Fillmore and the newer areas like the Tenderloin, the local dance halls and bars (or after

Figure 4.22

A plain saloon. After work hours, construction workers mix with young clerks in this San Francisco

saloon. Note the lunch counter at the rear.

Prohibition, the local lunch counters) often had a group of regular neighborhood customers. To the horror of her colleagues, the sociologist Margaret Chandler found a high degree of social cohesiveness in these groups. Social circles focused on one person's room or more frequently around a particular lunch counter, bar, or street corner. Some lunch stand groups behaved much as they might have in small towns. People stopped several times a day or night; on occasion, owners cooked up special meals for their regulars and extended them credit.[74] This social cohesion stood in sharp contrast to the alienation, anonymity, and illegal behavior that also characterized the mixtures of rooming house districts.

Beyond the Edge of Propriety

For people who wished to be anonymous and unnoticed, life in cheap hotels could be ideal. In a rooming house district, a small town Simple Simon might be teased less than he had been at home. People who wanted to live a liberated or illegal life

could do so in rooming houses and lodging houses more easily than in most other settings. For alcoholics or drug addicts, the fear of being discovered, the desire to be near some people like themselves, and the need to be close to supply sources brought them to hotels. Addicts could have seclusion if they wanted it, and desk clerks fended off investigators and pesky caseworkers.[75] Landladies might not remember or even know a new tenant's name. The frequent change of address possible at hotels, perhaps with a corresponding change in name, helped runaways elude their parents, reformed people escape their past, and criminals evade the police.[76] For anyone who wanted to melt into the physical maze of the city, such anonymity and the large number of rooming houses offered the perfect settings.

Given the large number of people seeking entertainment and anonymity in rooming house districts, red-light or vice zones logically overlapped with rooming house areas. In 1910, three-fourths of the parlor houses in American cities were in the rooming house and tenement fringes of the central business district. The architectural arrangements for small rooming houses in the 1910s could be almost identical to those built for parlor houses: rental store space on the first floor—inevitably a saloon in houses of prostitution—with parlors and the madam's suite on the second floor and many bedrooms on the third floor. For the prostitute residents, the madam's parlor house functioned as a boardinghouse or rooming house. A madam often listed her business in the city directory under the category of lodgings; notorious black sex clubs were sometimes advertised as buffet flats.[77] This overlapping of hotel life and prostitution was heightened in New York by a state vice law of 1896, which inadvertently produced "Raines Law hotels." Under the new statute, saloons could no longer offer free lunches, and hotels alone could sell liquor on Sunday and then only with meals. "In consequence," complained one legitimate New York hotel keeper, "every gin-mill in New York is now a hotel. It is easy to create a hotel. All you need is 10 microscopic bedrooms and some permanent sandwiches." At the turn of the century, Manhattan and the Bronx had 1,407 certified hotels, and 1,160 of them had apparently sprung up in response to the Raines Law.[78]

By the 1920s, decreases in general prostitution ironically led to an increase in prostitution in hotels. Business for women prostitutes had declined with the rise of the flapper—or more correctly, with shifts in

social mores for women that allowed women to be more sexually active and independent. Prohibition and Progressive Era attempts to protect young men—particularly the soldiers of World War I—from the Victorian versions of prostitution had decimated the flagrant red-light districts of many cities. Growing use of the automobile for sexual encounters moved prostitution to new locations. For the prostitution that remained downtown, hotels played a larger role as prostitutes' homes and as places of assignation. In San Francisco, a major vice crackdown of 1917 saw police raiding "hotels, lodging houses, and flats on streets which had never before known a house of prostitution." In national surveys in the 1920s, streetwalkers were found to be operating out of hotels twice as often as old-style bordellos.[79] Any of these social problems at times led rooming house residents to look for other housing options.

Downtown Alternatives to Rooming Houses

At least according to social ideals, if roomers left rooming house life, they either joined the protective circle of a private family or began to cook for themselves. In so doing they stepped up in status. While living with a family or cooking for themselves they were less overtly dependent on commercial entertainment and public dining, and less involved with the tainting mixtures of rooming house districts. However, both family and apartment alternatives confronted rooming house residents with serious problems. Living with a family worked directly against the individualism so encouraged by work places and youth culture. The limited and erratic income of rooming house residents militated against proper apartment life. The apartment option that roomers could afford, the light housekeeping room, actually lowered their status.

Problems of Living with a Downtown Family

Boarding or lodging with a family was the major alternative to living in a commercial boardinghouse or rooming house, and it was also the most commonly chosen downtown life-style for young single men and women. For families in the middle and upper class, boarders were extra income, companionship, or people taken in as a favor to relatives. In such households, boarders often filled unused rooms. For wage-labor families with irregular incomes, boarders were essential. The income they

Figure 4.23

A Slavic boardinghouse dining room in a factory district near New York City, 1912. Photographed

by Lewis Hine.

provided helped to pay medical bills or make monthly payments on a looming seven-year mortgage with a balloon payment at the end. Boarding with families was particularly common in working-class family districts and family slums, often located next to rooming house districts because their residents depended on many of the same kinds of jobs (fig. 4.23).

Boarding with a family offered more traditional home-style conviviality, more social respectability, and generally better food than hotel life. Immigrants tended to board for only a short time and then set up independent households.[80] Unlike immigrants, American-born migrants to the city often chose boarding as a long-term housing choice. The eighteen-year-old lumber clerk, Will Kortum, had started his San Francisco life in a hotel in 1905 but soon wrote home that he planned to move in with a family in a nearby working-class district:

I am getting tired of this hotel and restaurant life and as soon as my pay is raised will look for board in a private family. . . . They say that . . . if you are lucky it is just like being at home.[81]

Figure 4.24

Flats and single-family houses at the edge of San Francisco, ca. 1890s. Roomers who stayed with families

in such settings were isolated from downtown life.

Kortum moved into a private boardinghouse on Eleventh Street, in the South of Market area, where he lived with the housekeepers—a young Swedish woman and her little girl—and seven other paying guests. He found that boarding with an immigrant family meant a sharp decline in personal comforts:

The meals are good, at least they are a great improvement in the restaurant fare, but otherwise there are but few comforts: no water in the room, poor bed, very small room, and bare of furniture. I shall look around for something better and wish I had never moved here at all.[82]

Kortum's new room supplied fewer personal needs independent of the boarding household. "My moving is an easily accomplished act," he said, "but costs 50 cents every time so I must be more careful."

This dissatisfaction with boarding with a family matched a general trend. Many boarders sought more independence and freer association with friends. Young people who lived in outlying family districts had a half-hour streetcar ride every time they wanted to visit companions, go dancing, or see a movie (fig. 4.24). Returning home, family boarders had to worry about missing the last streetcar for the night.[83] Other concerns were about privacy, as reported in this case:

"Miss G.," a public school music teacher, did not like rooming with a family. When she had phone calls, the family had to listen to one end of the conversation. If she slept late on Saturday morning she felt she was inconvenienc-

ing the family—and the children made such a ruckus she could not rest anyway. . . . She repeatedly took guests for a walk rather than use the parlor.[84]

Another woman complained, "The family from whom I rented a room were inquisitive and prying. I'm sure they investigated my room during my absence. The bathroom was occupied for prolonged periods."[85] Once these women had sampled the personal freedom and independence of hotel life, they felt that it would be impossible for them to board in a private home again. Lily Bart, Edith Wharton's heroine in The House of Mirth , eventually chose the anonymity of a commercial boardinghouse over living in a friend's house. To Lily, "the promiscuity of small quarters and close intimacy seemed, on the whole, less endurable than the solitude of a hall bedroom in a house where she could come and go unremarked among other workers."[86]

Light Housekeeping Rooms

Light housekeeping rooms were the cheap apartment-style alternative to rooming house life. They were typically one- or two-room suites in flimsily adapted former houses or apartments, usually in declining neighborhoods (fig. 4.25). By the 1920s, the hallmark of a housekeeping room was the "ubiquitous gas plate" on an old crate in a corner of the bedroom, with a rubber hose leading from it up to the wall gaslight fixture.[87] To keep cooking grease from splattering the wallpaper, tenants pinned newspaper against the wall. A pail of water might serve as a sink. There was usually an improvised pantry made by a large soap box, with cheap curtains on the front. Elsewhere, housekeeping meant simply that several tenants shared both kitchen and bath. Managers of light housekeeping units typically supplied a table, two chairs, a bureau, a few dishes, and a few cooking utensils.[88] As with rooming houses, daily management was left to resident women who leased the buildings as a business. By all accounts, housekeeping rooms were sanitary and social problems. They were technically not hotel units because of their cooking arrangements, although some surveys included them in the ranks of single-room occupancy. Even when owners borrowed names like "apartment hotel" or "residence club" for their furnished room buildings, the lineage of these operations led directly back to the worst nineteenth-century slum traditions. In 1939, two-fifths of San Francisco's substandard housing units were housekeeping rooms. The advantage for the landlord was

Figure 4.25

Kitchenette apartment buildings (light housekeeping rooms) on South

Parkway in Chicago, 1941.

income: a building cut into two-room units brought twice the monthly rental income that it produced as five-room flats.[89]

Housekeeping rooms were often crowded by families who had fallen on hard times; social workers called them "dejected families" (fig. 4.26). Unlike poor immigrant families in tenements, tenants in housekeeping rooms were usually born in America and often white. Their trip to housekeeping rooms began when they defaulted on the mortgage on their house, stored their furniture, and moved into some sort of hotel while the breadwinners recovered from illness, continued to drink, or looked for work. If the family's finances continued to decline, they often lost their furniture for nonpayment of storage fees.[90] Thus, they found themselves locked into life in housekeeping rooms. Other families came to choose it over the option of having a full-fledged apartment; when social workers helped them obtain a flat and furniture, the families moved right back into cheap furnished rooms. For such households, the social workers reserved the labels "shiftless" and "tramp families."[91]

More expensive apartments were usually out of the question for people in the rooming house price range. The barriers were entry costs and application barriers more than the monthly rents. Matrons in the YWCA cautioned that "it was a risky thing for two or three girls to take an apartment together" because "if one dropped out the remainder were then forced to bear the financial burden" until a new room-

Figure 4.26

Housework in light housekeeping rooms in Chicago, ca. 1929. Note the rubber tube connecting

the gas wall fixture to the hot plate.

mate could be found.[92] Even when respectable and inexpensive downtown apartments became more available, young single people had neither the nest egg nor the job security to buy the furniture, linens, and kitchen equipment that apartments required. Unmarried or poorly employed people also had a slim chance of getting a lease from apartment managers. Furnished one-room efficiency apartments solved some of these problems, but at $25 to $30 a month they were beyond economic reach. They outpriced an unfurnished four-room garden apartment in the suburbs (table 2, Appendix). So, until their income improved, the low-income renters stayed in housekeeping rooms or in a rooming house.

Scattered Homes versus Material Correctness

Whether rooming house tenants lived in a converted single-family house, a generic loft, or a purpose-built rooming house, their home was scattered up and down the street. They slept in one building and ate in

another. The surrounding sidewalks and stores functioned as parts of each resident's home: the dining room was in a basement near the corner of the block, and the laundry was three doors over; the parlor and sitting room were at a bar, a luncheonette, a billiard hall, or a favorite corner. Residents of midpriced and palace hotels could use their neighborhood as their homes, too, but for them it was a choice; the more expensive hotels, with their full housekeeping and dining services, were self-contained like private houses.

The scattering of the home reflected the increasing social and cultural autonomy that some young men and women expected. Their work lives also encouraged them to be footloose and independent. Hotel life allowed all tenants—especially single people—to push that personal privacy and autonomy to a new limit. This was a schism between the family districts of the city and the places that embodied nonfamily life. Rooming house life plugged the individual directly into the high-voltage currents of the industrial city—liberation and independence very different from that offered by a room of one's own within a family.[93] The hotel room, even with the acoustical group life that remained in cheaper hotels, was unhinged from the social contracts, tacit supervision, and protection that went with most other types of household life. Absent were the architectural arrangements so important to the maintenance of the nuclear family concept and family proscriptions of behavior.

As Joanne Meyerowitz has observed, the people in the rooming house areas of American cities were leaders in the increasing secularism and decreasing moralism that were reactions to Victorian mores. Of all the social experimentation that rooming house areas supported (and that the urban economy had engendered), most notable were new rules for sexual and social relations between men and women. In rooming houses, men's and women's lives crossed constantly. Gendered realms were scarcely circumscribed in the way that suburban or rural standards prescribed and that the spatial arrangements of polite households reinforced. Single women in rooming houses shared hallways with single men, without any familial or community supervision. Unlike the better hotels, in rooming houses there were not even servants or clerks to observe the activity.[94]

By the 1890s, rooming house areas had earned a reputation for what we would now call a sexually integrated youth subculture. Later, taxi-

dance halls, movies, Bohemian restaurants, and cabarets opened the subculture into a wider commercialized landscape of personal desire. An emblem of this different subculture in the years before the depression was the fact that rooming house districts were areas where women could smoke and dance in public.[95] For young people in family districts, such recreations were optional excursions. For rooming house tenants, they were part of the daily walk to work, and part of their home scattered up and down the street.

Not all rooming house life constituted a culture of opposition, however. In their new social and sexual public lives, rooming house residents may have been flappers or dance hall sheikhs; they may have openly flouted a great many values of the middle and upper class. They were using rooms in new ways, but they held on to the material propriety of the middle and upper class, especially in relation to individual life in their own rooms. Their concerns about room furnishings suggest that their rooms—not their favorite café or dance hall—stood most clearly for their personal selves and their places in the world. As one social worker put it, turn-of-the-century clerks and secretaries had personal standards higher than commercial wages would justify.[96] They managed their marginal economic and cultural status by keeping one foot in rooming house culture and another in the material culture of private family life.

In 1905, Will Kortum showed his concern with family standards by his choice of building and room furnishings in San Francisco's South of Market area. On finding a place to live, he excitedly wrote home, saying that on his first day in town he had found a fine place to live:

The hotel is a new one, not entirely completed and everything is neat and clean, although not large. My room is very light, has hot and cold water, double bed, bureau, wash stand, chair, and small table. [It also has a] closet for clothes.[97]

In fact, Kortum had found a good building—a six-story hotel with an elevator and over half of its street length devoted to its own lobby and saloon.[98] However, his father expressed concern over the choice, and rightfully so: Kortum's hotel was only a hundred yards from the very center of San Francisco's hobo labor market. A few days later, the young man wrote this back to his father:

Rest assured that my present place of lodging is no low class hotel, but a clean, plastered room and that the bed is also clean and comfortable.[99]

Figure 4.27

Diagram of the Delta Hotel second-floor

plan, comparing the regularity in the

shape of the private rooms and the

snake-like public hall space.

Kortum's letters show all the material concerns we would expect of someone brought up in a respectable middle-income family house in a small California town of the 1890s. He noticed that the room was "not large" but "very light." He listed the pieces of furniture carefully; he had plainly seen less attractive rooms at this price range. Other key words were also there: "clean room," "clean bed," "not a low class hotel." He had an individual sense of the line between the propriety of the middle and upper class and the hygienic problems of some working-class life. His room was in every way proper. But he had not yet learned caution about living above a saloon or being associated with a casual laborers' neighborhood. Kortum's decent room, with its minimal pieces of furniture, was clearly his material foothold in the realm of middle and upper class culture. Furniture lists set out by people such as Will Kortum and Dorothy Richardson are practically a mantra in the literature of rooming house life.[100]

In architecture, too, owners and designers gave individual rooms the most attention. Floor plans of purpose-built rooming houses emphasized small, nearly square rooms, all of a similar size and with reasonably equal access to light wells. A diagram of the rooms at the Delta Hotel of 1906, for instance, shows this regularity and the primacy of individual space (fig. 4.27). Owners and landladies knew that rooms like these would rent. In sharp contrast, the hallways and public spaces

of rooming houses were often leftover labyrinths. The twisting hallways mirrored the convoluted social lives of rooming house residents, fashioned between the interstices of work and personal identity. Plans like those of the Delta Hotel were very much against the architectural conventions for hotels of the midpriced or palace rank, where owners and designers strove to keep hallways far more presentable and regular.

Thus, even single rooms and their furnishings were important anchors for people in a social and cultural limbo. To confirm further that they still had some claim to social and cultural propriety, rooming house residents only had to compare themselves to the denizens and material culture of the least expensive rank of hotel life, the cheap lodging houses.