Alternative Quarters

In addition to the classic example of a hotel purposely built as a midpriced hotel, middle-range hotel options came in at least four other modes: back halls of palace hotels, formerly grand hostelries, converted houses, and residence clubs. Apartment options at this price range, not readily available in 1880, became far more accessible both in number

and in price between 1910 and 1930. The different types of midpriced hotels showed more variation than did palace hotel life, in part because midpriced hotels served a much larger and more scattered market. In most cases, however, the midpriced hotel matched the values and norms of the middle and upper class, albeit sometimes with difficulty.

Variations of the Midpriced Hotel

If a young business person of moderate means hoped to rub shoulders with upper-class investors, his or her most logical choice of a hotel home would not have been living in a midpriced enterprise at all but rather renting a back hall room at a palace hotel. Few palace hotels could be as imperious as Boston's old Tremont House, which charged only one high rate. Prices usually varied widely. Jefferson Williamson notes that before the Civil War the grandest hotels—those advertising prices of $2 a day for board and room—offered "in profusion" 50-cent or $1 accommodations for lesser rooms.[55] As hotel owners installed indoor plumbing, prices of rooms with a private bath could be two and a half times greater than rooms in the same hotel but with a shared bath down the hall. Hotel architects relegated such rooms to areas along alley walls, in noisy corners of the building where the only light came from narrow air shafts, or where the occupants would have no view (fig. 3.15). In the 1920s, managers at the Chicago Beach Hotel on Lake Michigan charged a middle-income rate of $56 a month for a room without bath in an old wing built in the 1890s; meanwhile, lakeview suites in the newest section started at a princely rate of $700 a month.[56] Even the lower-priced rooms at a palace hotel had the advantages of service, public rooms, and general prestige. But they betrayed themselves in social engagements. "No, don't bother to come by our rooms, we'll meet you in the lobby," was the refrain of back hall hotel residents. Middle-income residents could also locate their hotel home in a palace hotel that had fallen slightly from social grace, thanks to the real estate process known as filtering. If palace hotel tourists shifted to a more fashionable hotel, the rents in the older building usually dropped into a range affordable at middle-income levels.

Small hotels at the lower end of the midprice rank hung on to their social class respectability with difficulty, and their amenities sometimes ranged precariously close to their poor relatives, the rooming houses. To qualify socially for residents of middle income, even the smallest

Figure 3.15

Plans for the ground floor and a typical upper floor of the Hotel

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, published in 1924. Single hotel rooms

are at the back, suites at the front. Unusual room labels include

H.R . for single hotel rooms and S.P . for sleeping porches.

Most living rooms have Murphy beds.

hotel had to have a lobby and a dining room on the ground floor (fig. 3.16). For the smallest midpriced hotels, architects tucked cafés or dining rooms into the back of the building, under skylights at the bottom of light wells, or into reasonably well lighted basements. Better room furnishings, more unctuous staff, and having an elevator also helped to distinguish small midpriced hotel buildings from mere rooming houses.[57]

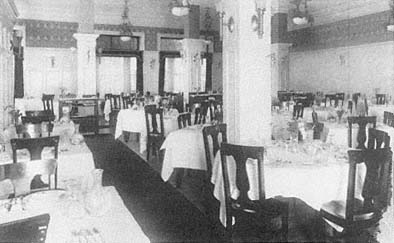

Figure 3.16

The dining room of San Francisco's Hotel Cecil. With a fairly low ceiling

and awkwardly placed columns, this dining room was architecturally

a step down from the dining room of the Delmonico Hotel but

still proper for middle-income patrons on a tight budget.

These smaller hotels descended from the long nineteenth-century tradition of respectable boardinghouses—single-family houses converted to commercial housing use. To attract people with polite middle-income pretensions, either the food offered or the architecture of the original house had to be quite grand. Two San Francisco houses in the lower Nob Hill area, both converted to boarding operations by the 1880s, show the edge of social propriety (fig. 3.17). Miss Mary J. Fox and Mrs. Robert McKee rented out rooms or suites of rooms in their modest houses on Post Street near Jones. They borrowed social sheen from the much larger houses a block uphill to the north, on Sutter Street. Behind Miss Fox's house loomed a new building, the Berkshire family hotel, a four-story brick building with an elevator (a luxury feature for a hotel of its size at that time). Early insurance records simply called the Berkshire a private hotel, but it was one of the city's best family hotels, the fourth largest one opened in the city. Like the small converted houses nearby, the Berkshire was managed by a woman. By 1900, because of the built-in amenities in structures like the Berkshire, only if a single-family house were very large and opulent, perhaps built by a well-known family, could the owners convert it and charge middle-income rates.[58]

Beginning in the 1880s and continuing through World War I, real estate speculators also experimented with midpriced hotels in the suburbs. In a large and proper suburban area, developers often included

Figure 3.17

Axonometric drawing of a lower Nob Hill neighborhood in San Francisco,

1885. Single-family houses are mixed with boardinghouses (shaded)

and the Berkshire, an expensive residential hotel with an elevator.

a snowy hotel—part real estate office, part residential building, part country club. In the San Francisco region, the Claremont Hotel is a quintessential example (fig. 3.18). It opened in 1915 on a wooded site with a creek and sixteen acres of gardens at a prominent overlook at the end of a major interurban transit line. Naturally, the land development company itself developed the rail line and advertised their hotel as "five minutes from Berkeley, fifteen minutes from Oakland, a half-hour from San Francisco." Two hundred rooms, half with baths, were in a 700-foot-long wooden building with 500 linear feet of porches looking out over a spectacular view of the hills, the bay, and San Francisco. Streetcars and carriages entered on one side, where there were also large stables; automobiles had a separate porte cochere and garage on the other side.[59] Below the hotel on three sides were devel-

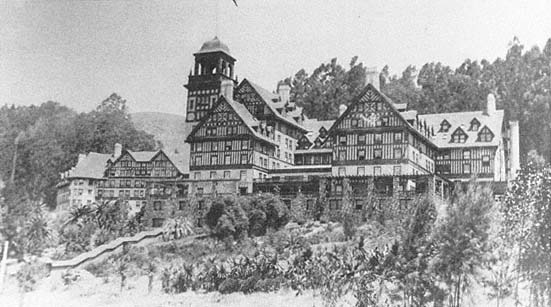

Figure 3.18

The Claremont Hotel in Oakland, California, a classic example of a suburban resort and residential

hotel, opened in 1915. It was located at the end of an interurban line from San Francisco and was

surrounded by expensive house lots.

opments of substantial new suburban houses for the middle and upper class. The residents of these houses were expected to be frequent diners at the hotel.

Other suburban midpriced resort hotels were on beachfronts, lakesides, or hilly wooded lots along a stream. Some country clubs also had sleeping rooms, eventually used permanently. Yet after 1920, as a result of zoning restrictions and suburban market realities, further developments of such outposts of urbane commercial life were to be overwhelmed by garden apartments and rules prohibiting the mixture of uses that the Claremont Hotel meant for its surrounding neighborhood.

Residence Clubs

At the least expensive end of the midpriced hotel social spectrum were residence clubs offering midprice hotel amenities at a budget price. Like their plebeian cousins (the YMCA or YWCA) and also their rich uncles (exclusive private clubs), commercial residence clubs usually were tailored for single men or single women. A few clubs accommodated both single men and women by having them live on separate floors—a policy rarely used in public hotels.[60] Allerton Houses, Ltd., seems to have built the first large buildings of this type in New York just after 1900; developers in other large cities followed suit. Managers pared costs by providing very small rooms—almost exclu-

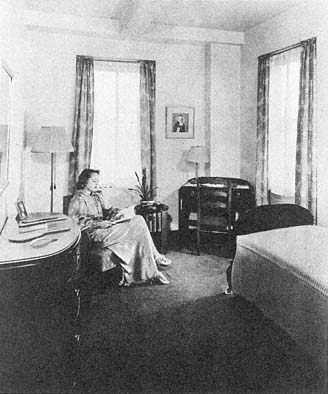

Figure 3.19

Room view from a 1939 brochure for the Barbizon Hotel,

New York City. The text emphasizes a "home away from

home" with "full-length mirror, no-draught ventilators,

three-channel radio, convenient electrical outlets."

sively single rooms—with day beds that converted to couches. Typically, about three-fourths of the rooms had a private bath.

Life in the residence clubs was like life in a YMCA but without the "C." The clubs kept staff to a minimum, especially in food service. Typically each club had its own restaurant and cafeteria or a restaurant that ran on self-service lines for breakfast and lunch and provided table service for dinner.[61] Perelman remembered a rather upscale residence club with a ground-floor coffee shop with waitresses in peach-colored uniforms who served a thrifty club breakfast costing 65 cents. "You had a choice of juice—orange or tomato," he wrote, "but not of the glass it came in, which was a heavy green goblet. The coffee, it goes without saying, was unspeakable."[62] Compared to private boardinghouses, residence clubs offered more flexible dining hours in addition to lower costs; compared to the Ys, clubs were a hefty notch higher in cost but offered more privacy and less supervision. New York's twenty-two-story Barbizon Hotel, built in 1927 and operated as a women's hotel until 1981, stood at the top of the midprice residence club scale (fig. 3.19). The women who lived there had at their disposal musical

evenings in the lobbies, a swimming pool, a gym, and a library. In hard times, a cherished tradition of the better clubs was a free daily teatime in the lobby. At one club, which tended toward a literary crowd, during teatime the lobby was said to take on the air of a book-and-author luncheon. At the Barbizon, girls on a tight budget frequently made their largest meal of the day out of the bite-size complimentary sandwiches.[63]

Apartment Hotels and Efficiency Units

Furtively cooking in one's room or continually eating in restaurants could be major irritations and expenses of hotel life. Residents who liked other aspects of downtown life often welcomed the development of affordable downtown housing units that offered private kitchens. By the 1920s, apartment hotels and efficiency units, often rented complete with furniture and dishes, were the principal downtown competition for midpriced residential hotels.[64] The typical mix of services is shown in this advertising copy from a 1920s brochure:

Exclusive Apartments—Hotel Service: The Plaisance contains 126 apartments of one to four rooms, all beautifully furnished and completely equipped. All with private baths—the four-room apartments with two baths. A large lobby, parlor, ladies parlor, and general dining room are situated on the main floor. There are shops necessary to insure comfort and convenience for the guests of the hotel. . . . Every apartment has a breakfast room and buffet kitchen completely equipped.[65]

In apartment hotels, buffet kitchens or service pantries were small kitchens with a minimum of counter space but a full-sized sink, an ice-box or refrigerator, and at least a double hot plate and a warming oven, if not a full cooking stove. Tenants in an apartment hotel could cook, take their meals in the public dining room, or (for an extra fee) have meals served in their own suite using their own silver, linen, and china if they chose. The staff of apartment hotels often took over window washing and making the beds along with periodically scouring the sink, icebox, and cupboards.[66]

Apartment hotels were often outside of downtown on parks or parkways, along major avenues and streetcar lines, adjoining new suburban apartments, or replacing former downtown mansions. In 1929, a nationwide survey revealed that apartment hotel buildings were typically large—100 units with an average of 2.7 rooms each—and most rooms

Figure 3.20

Plan of a typical efficiency apartment, published in 1924.

were rented furnished. About half of the buildings had separate maid's rooms and garage space available to tenants.[67] By the 1920s, design guides identified three distinct price ranges. Expensive examples offered full apartments with all the public rooms and services of midpriced hotels. Medium-priced examples had a lobby, desk staff, a ballroom, a billiard table or two, and a roof garden. The least expensive buildings had only switchboard service and porters for ice, groceries, garbage, and errands. These buildings more closely resembled average efficiency apartments.[68]

The minimum apartment for the middle-income household was the efficiency apartment, perfected between 1900 and 1930 (fig. 3.20). At about $25 a week (in 1920s prices) efficiency apartments were bargain versions of the apartment hotel, which started at about $50 a week (table 2, Appendix). The central innovations of efficiency apartment designs were folding beds—doors with attached, spring-loaded bed frames. These allowed tenants to turn the bed upright and pivot it into a closet or dressing room. The most common brand, the Murphy bed,

was named after a San Francisco manufacturer. Rebuilding after the 1906 fire, together with the general population and building boom on the West Coast, created such a large initial market for Murphy's new folding beds (and for a host of early imitators) that journalists reported the efficiency apartment itself had originated in California. Like so many other apartment innovations, Murphy beds had been initially marketed primarily to hotels.[69]

By 1911, the tiny kitchen areas in efficiency apartments (originally called buffet kitchens) were common enough and socially correct enough in San Francisco apartments so that local housing reformers gave them special consideration in proposed housing laws. By the 1920s, similar six-foot by eight-foot rooms were popularly called kitchenettes. They epitomized the simplifications in cooking and reliance on packaged foods that also marked smaller kitchens in new single-family houses.[70] Unskilled women working in canneries and food processing plants were doing many of the food preparation steps formerly done in individual kitchens.

Compared to tenement flats, apartment hotels and efficiency apartments were expensive. To live cheaply and comfortably in a middle-income apartment, single people either had to have quite a high income or had to relinquish their independence and team up with roommates. Group living proffered certain benefits—among them, regular company at meals and better space. Not everyone, however, wanted a roommate, and few apartment landlords wanted to rent to nontraditional household groups. Edge-of-the-city apartment complexes of the time were not a strong alternative for single people. As late as 1942, Parkchester, with its 12,000 units in the Bronx, had fewer than a dozen single people living in their own apartment, and those residents were mostly retired. The adjacent Hillside Homes project had 1,410 families but only 14 unattached people.[71]