The Classic Midpriced Hotel

In Victorian Chicago, the woman retailer who was a single parent or the enterprising New England mill representative and his wife might have chosen as their place of sojourn a building like Chicago's Hyde Park Hotel, built in 1887–88 (fig. 3.7). It had an open rectangle plan that left an ample light court for the inner rooms, a huge skylit lobby, and a first floor devoted to public rooms. Throughout the hotel were electric lights, telephone service, electric call and return bells, and steam heat for three hundred rooms arranged in two- and five-room suites. In the 1890s, many similar hotels labeled as "family hotels" or "private hotels" took few, if any, transient guests. Guests typically leased rooms by the year and decorated their rooms as they would a private house. Demand in San Francisco was such that applications for suites in new family hotels were often made six months before the building was finished. By the turn of the century, most large cities had rows of buildings with similar features on a few respectable streets or boulevards.[36]

Figure 3.7

The Hyde Park Hotel in Chicago, opened in 1887. It featured two-room to five-room suites and was

located at Hyde Park Boulevard and Lake Park Avenue. Photographed ca. 1928–1930.

By the 1920s, the most common suite in a midpriced hotel was two rooms, and use of those rooms varied. One occupant interviewed at that time had a parlor with a western exposure facing a park. He had brought in his own table, lamps, chairs, bookcase, and pictures. Elsewhere, a woman and her adult daughter shared a two-room suite. A Murphy bed in the parlor meant that at night each of them had a private room.[37] S. J. Perelman gave this graphic description of a single room in New York's Hotel Sutton, a midpriced residential hotel intended primarily for single people. The description could double for the modal midpriced hotel room:

The decor of all the rooms was identical—fireproof early-American, impervious to the whim of guests who might succumb to euphoria, despair, or drunkenness. The furniture was rock maple, the rugs rock wool. In addition to a bureau, a stiff wing chair, and a lamp with a false pewter base and an end table, each chamber contained a bed narrow enough to discourage any thoughts of venery.[38]

Had Perelman given a more complete furnishings list, he would have noted that the interior designer had specified the wing chair and its floor lamp in addition to a desk, a desk chair, and a desk lamp.

Perelman's room was not large enough for a dining table, which some larger midpriced hotel rooms had, but in many such hotels the guests could give dinner parties in private dining rooms near the lounges and lobbies.[39]

Midpriced hotel buildings could be very small (figs. 3.8, 3.9). Some, for instance, contained only twelve rooms (several with fireplaces, perhaps), all tucked within a 25-foot-wide building on a narrow downtown lot. At the other end of the scale, midpriced hotels could be notable structures of three hundred rooms with meeting facilities.[40] By the turn of the century, in hotels intended to have a mixture of permanent and transient guests, architects often included, off the lobby, a mezzanine floor with a more private parlor, sometimes including a piano, for the use of residents. These spaces probably evolved from the special ladies' parlors that most large hotels furnished through the turn of the century. The mezzanine floor offered conviviality with less overt supervision from the ground floor desk. Some residents also preferred hotels with side corridors to the street or cafeteria so they could avoid the public lobby and the routine surveillance of the hotel desk clerks.[41] Due to a series of public spaces reserved for them, especially before the 1930s, women in polite hotels could also have an experience of hotel life largely separate from men. Some hotels had a separate women's entry, different lounges, separate women's coffee shops, and different house rules. Likewise, the billiard room, barroom, and some lobbies and reading rooms were largely men's turf and off-limits to respectable women.

Degree of personal service and amount of plumbing distinguished the social rank of a midpriced hotel just as surely as the size and furnishings of the guest rooms. While palace hotels employed from one to four servants for each guest, one employee for every two guests was the norm in midpriced hotels through the depression. People on tight budgets who lived in hotels noticed that chambermaids went first to the larger, expensive suites and cleaned better there because those tenants could afford higher tips.[42] Plumbing saved on servant expense and drudgery, and more plumbing per room was particularly notable at the turn of the century. In 1875, the Palace in San Francisco had a bath for every room, but not until 1907 did a midpriced hotel make the claim of every room with a bath.[43] By about 1910, in midpriced hotels virtu-

Figure 3.8

Typical upper floor plan of the Ogden Hotel, Minneapolis, built in 1910.

Fairly large rooms, Murphy beds, and private baths helped to make

this a socially correct hotel for middle-income tenants.

Figure 3.9

Basement floor plan, Ogden Hotel, Minneapolis.

Note that the dining room (DR ) has a separate entrance from the outside

for nonhotel patrons. The kitchen (K ), pantries and storage rooms, and

an apartment for the manager (M ) filled out the floor.

ally every bedroom offered at least a room sink with hot and cold water. This provision had become common in private houses and hotels for the same reason: carrying water to the bedrooms was one of the onerous repetitive tasks required of the servants. In hotels of 1910, however, providing a full bathroom for every room was not yet common. About half the rooms had a private bath, and the rest shared hall bathrooms. Only by about 1930 did new hotels of this rank offer a private bath for every room.[44]

In small cities one building often had to serve as the equivalent of the town's palace hotel as well as its best midpriced hotel. Design guidelines for such hotels in 1930 noted that if 20 percent of the rooms had private baths, that was sufficient. Another 50 percent of the rooms were to have half-baths (basins and toilets), and the remainder of the rooms were to have simply room sinks and shared baths down the hall.[45] The hotel's date of construction often determined its precise bath ratio as well as the relative size of light wells and other amenities (fig. 3.10).

Figure 3.10

Comparison of typical 1907 and 1927 light wells in San Francisco.

Because the earlier building codes (right) had minimal

requirements, the light wells of midpriced hotels built

before World War I were much smaller than those

of a typical hotel of the 1920s.

Together, these features set the hotel's intended socioeconomic strata for at least its first generation of clients.

The plumbing and heating in midpriced hotels were often better than their counterparts in most private houses. In the mid-1800s, public rooms and corridors in hotels had steam heat; hotel bedrooms had individual stoves and fireplaces long before the bedrooms in average houses. Europeans soon began the tradition of complaining that Americans overheated their buildings. In later hotels most Americans first experienced the luxuries of indoor plumbing, push buttons, and iced or hot water readily on tap.[46] In the 1920s, such material comforts still contrasted sharply with life in most private houses. Residents of midpriced hotels of the jazz age repeated litanies of service and comfort heard only in palace hotels the generation before:

Life is luxuriously comfortable. . . . The idleness, the heat, the comfort [are totally unlike a family house]. . . . I have four towels each day, fresh sheets several times a week, hot water at any hour, lots of light and heat and a private bath. In the hotel are a restaurant, laundry, dry-cleaning establishment, bootblack, and many mail deliveries a day.[47]

Figure 3.11

Sunday dinner menu from the Hotel Beresford

in New York City, 1915.

Luxury, wrote one architect, was hotel living's outstanding characteristic and best drawing card; hence, attention to luxury was essential even in midpriced hotel design and especially in the public spaces.[48]

Large midpriced hotels always had an imposing lobby and a well-appointed dining room for full, leisurely, and fairly expensive meals (fig. 3.11). These spaces, along with the ballroom, bar, and breakfast room, were where the scale and social impressiveness of a public mansion could best be experienced. By the time of World War I, visitors could also expect to see the terms "café" or "coffee shop" used for casual lunchrooms in hotels. "The coffee shop idea," wrote a hotel kitchen expert in 1924, "seems to have completely uprooted the dairy lunch and cafeteria service of a few years back, and along with it the grill or grill range has replaced the long steam table."[49] Two residents on a tight budget told Hayner that they rarely used the elegant ground-

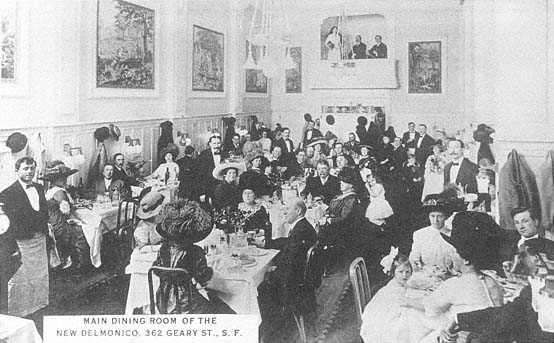

Figure 3.12

Postcard view of the Delmonico Hotel dining room, in San Francisco. The tall ceiling and musicians'

gallery set the tone for the room. European plan pricing allowed residents at midpriced hotels to sample

the fare at other restaurants.

floor dining room in their hotel but ate instead in the basement café. With food smuggled in from the outside, they also routinely stretched a room service meal for one into a meal for two. The smell of food illegally cooking on alcohol lamps or electric hot plates was known even in very fashionable hotels.[50] Many hotel managers eventually gave up the battle against long-term tenants cooking in their rooms and installed permanent hot plates or kitchenettes in some suites (depending on prevailing building codes). In the forty-nine largest palace and midpriced hotels in Chicago in the early 1920s, about 8 percent of the units were full apartments with a kitchen.[51] Also, the managers of midpriced hotels were among the earliest hotel keepers to give up the American plan of combined board-and-room payment. Instead, they offered rooms on either the American or European plan (fig. 3.12).

Even with the cheaper European plan prices, to live with hotel advantages people with middle incomes had to give up space. If they had been renting a suburban house or a respectable five-room apartment, they had to accept either a very small suite in a good midpriced hotel or a larger suite in a less elegant hostelry. Hayner writes of a family of four, with children aged three and eight, who paid $650 a month for their large house in a Chicago neighborhood that had lost its cachet;

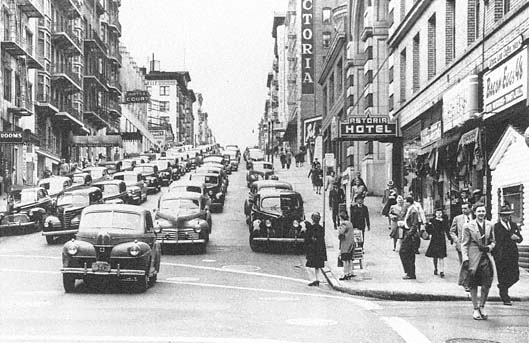

Figure 3.13

Bush Street near Grant, at the edge of a large midpriced hotel district in San Francisco, 1946.

While automobile drivers were stalled in traffic, hotel dwellers could always walk to work.

for $700 a month, they rented a small suite in a hotel on the fashionable Lake Michigan shore. He concluded that for families with incomes of at least $8,000 a year, hotels were cheaper than houses or large apartments of comparable social status.[52]