Self-preserving Associations

Exclusion or discrimination also pushed some middle-income people to live in hotels. Jewish people figured prominently in some midpriced residential hotel markets. In The Ghetto (1928), Lewis Wirth stressed that predominantly Jewish hotels had become the latest avenue of escape from some Jewish neighborhoods. Wirth noted that in both Chicago's Hyde Park and North Shore districts, a "Jewish hotel row" had begun to spring up, inhabited by middle-income business people and their families. In the Chicago Beach Hotel, for instance, 80 percent of the tenants were Jewish. Wirth felt that housing in more Anglo-American hotels offered Jewish people a ready avenue for mixing with Gentile society, a residential proximity not then possible in most expensive suburbs.[24]

The mistrust of actors and artists as residents in other types of housing brought them, too, to hotels. "Born in a hotel and died in a hotel, Goddamn it!" were the dying words of Eugene O'Neill. Indeed, until automobile travel, radio, and movies restructured the American entertainment industry, sojourning theatrical troupes were often part of a hotel's residential composite. Unlike O'Neill (who lived in a house most of his life), star actors as well as bit-part players could spend most of their adult lives in hotels; headliners, in palace hotels. Sarah Bernhardt required an eight-room suite when she was performing in San Francisco (fig. 3.5). In less-expensive New York hotels have lived stars such as James Cagney, Tallulah Bankhead, Sammy Davis, Jr., Bill Cosby, and Cher.[25] Yet because of some actors' mobility, Bohemian moral codes, perpetual swing shift hours, and high divorce rate ("seven times the average for all occupations," clucked one newspaper reporter), actors and entertainers were not very welcome guests. Managers sometimes looked askance even at opera stars and symphony musicians. In cities with a population of more than 100,000, the less famous entertainers could find a budget-priced and slightly dilapidated "theatrical hotel." Chicago had six theatrical hotels in or near the Loop; hotel guides marked these hotels clearly, in part to warn other travelers.[26]

So many writers, editors, and composers made midpriced hotels their homes that they became another distinct client group. Artemus Ward

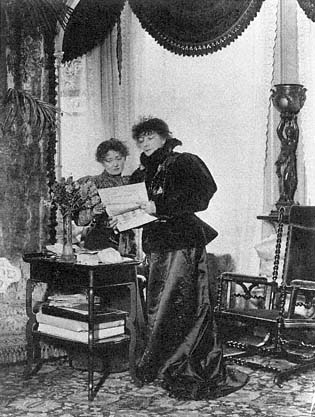

Figure 3.5

Sarah Bernhardt in her suite at the Hoffman House in

New York City, 1896. Among theater people, only

headliners could afford such expensive hotel homes.

lived in a hotel in New York's Greenwich Village when he came in the 1860s to edit the first Vanity Fair . Several writers made New York's Brevoort Hotel their home and through the 1880s mentioned life in the 100-room building in their novels. At New York's Majestic Hotel, at 72nd Street, another set of writers and artists congregated.[27] During two periods in her life, Willa Cather lived in a hotel: first, when she moved from Pittsburgh to New York City, and again in 1927, when building demolition forced Cather and Edith Lewis to move out of their apartment into the Grosvenor Hotel, at 35 Fifth Avenue. What they intended as a temporary refuge became their home for five years. Dylan Thomas and composer Virgil Thompson were only two out of many creative artists who made the Chelsea Hotel famous. Edna Ferber lived at the Sisson Hotel in Chicago. Nearer to the University of Chicago, Hannah Arendt and Thomas Mann each lived at the Windermere Hotel for part of their lives. Charlie Chaplin lived for a time in the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, and for almost fifty years the Am-

Figure 3.6

Advertisements for residential hotel life, 1936. Special monthly rates, social

activities, and good food were key promotional elements.

bassador was Walter Winchell's home.[28] The famous Round Table at New York's Algonquin Hotel met in the hotel dining room, but for the most part the members were not hotel residents.

Like most other downtown hotel residents, all types of creative artists thrived on hotel locations. These artists relied on and helped to support nearby restaurants, nightclubs, theaters, and other entertainments. A Gramercy Park hotel brochure in 1927 promised that its fortunate residents would "find themselves at the heart of the best New York can give."[29] Libraries, medical buildings, legal offices, and churches added to the downtown's convenience (fig. 3.6).

Retired and elderly middle-income tenants were also attracted to midpriced hotel life by the central access to recreation and downtown

services as well as the pedestrian independence hotels afforded. When the health of elderly hotel tenants waned, room service and hired nurses replaced their former independence. Throughout the history of inns and hotels, elderly people had been a proportion of the permanent residents.[30] Nonetheless, Sinclair Lewis's George Babbitt put retirement in a midpriced hotel in a dark light. Babbitt's in-laws had sold their house and moved to the Hotel Hatton in Zenith City, "that glorified boarding house filled with widows, red-plush furniture, and the sound of icewater pitchers." After a sad and soggy Sunday dinner, the Babbitts had to sit, "polite and restrained, in the hotel lounge, while a young woman violinist played songs from the German via Broadway."[31] Hayner's Chicago study gives the more positive example of the retired Martin couple, who had lived for twenty-five years in their own house in a small Illinois city and then for twenty-one years in various Chicago apartments. When their daughter married, the Martins moved to a hotel where they had often dined. Both of the Martins enjoyed dancing at the hotel. Mrs. Martin, an active woman in her late sixties, loved to be in the center of things and reveled in a crowd. When she was not in her room sewing for her nieces she was out shopping in the Loop.[32]

Not all hotel keepers wanted elderly tenants, healthy or not. "A nice old lady is nice," Ford said about elderly guests in his large midpriced hotel in New York, "but the average old lady is a troublesome boarder." Ford did not mention elderly men, but he continued, "When old ladies come to stay I don't try hard to cater to them. They go away. There's one hotel in town where most of them land."[33] Indeed, each city had several midpriced hotels with derogatory nicknames like "The Old People's Home" and coffee shops called "wrinkle rooms," even though no more than half of the residents at those hotels may have been elderly. Not all hotel residents were in such places. Kate Smith, for several years before her death in 1986, particularly liked to watch the ocean liners from her three-bedroom suite at the top of the Sheraton Motor Inn near the Hudson River and 42nd Street in New York.[34]

For all types of people, personal safety was a hotel attraction that many downtown apartment buildings could not match. Hotel desk clerks watched entrances around the clock; at intervals during the night, watchmen patrolled the halls checking for fire problems or situations amiss. When tenants had an emergency, staff were always on duty. People away from home overnight or for long periods of time

could leave with a sense that children, a spouse, or an elderly parent would be safer and have more readily available help than in a private home.[35]

Clearly, residents also came to live in midpriced hotels for emotional reasons as well as for practical and social advantages. The expanding local economies that helped to create jobs often meant an expanding supply of appropriate hotel buildings whose visual appeal, interior design, and gustatory delights helped to convince people to make the hotel their home.