Assists for Politicians and Young Couples

Given these virtues of centrality, sojourning politicians naturally made up a significant hotel residence group. Through the 1800s, each urban political party patronized a particular hotel, and politicians to this day often live in capital city hotels while legislatures are in session. When owners tore down the old Neil House in Columbus, Ohio, President Warren Harding wrote to the managers saying that the hotel had been the "real capitol" of the state. Huey Long maintained a suite at the elegant Fairmont Hotel in New Orleans, spending so much time there that Louisiana lore suggests that he built State Highway 61 from the state capitol directly to the door of the hotel for his own convenience.[12] The most famous hotel-dwelling politician was Calvin Coolidge. The thrifty Coolidge and his wife were very long term hotel tenants. They lived many years in a dollar-a-day room in the old Adams House of Boston (built in 1883). When Coolidge was elected governor of Massachusetts in 1918, on the advice of friends he moved into a $2-a-day room. In 1921, Vice President and Mrs. Coolidge moved into the same modest fourth-floor corner suite in the Willard Hotel that Vice President and Mrs. Thomas R. Marshall had occupied throughout Marshall's second term in the Wilson administration. In 1922, a Washington hostess tried unsuccessfully to establish a pretentious vice-presidential house. Coolidge himself quelled the move, saying that maintaining such a residence on a $12,000-a-year salary was out of the question. The Coolidges remained in their Willard Hotel suite.[13] More recently, Supreme Court Justices Felix Frankfurter and Earl Warren have lived in hotels.[14] For most of 1931 to 1934, early in his career in Congress, Lyndon Johnson lived at the Dodge Hotel in Washington, D.C. During the early years of the Reagan administration, Attorney General William French Smith and Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger settled at the Jefferson Hotel.[15]

Newlyweds often lived in hotels. In the last half of the 1800s, people considered it unremarkable when a young couple lived the first two or three years of their marriage in a good boardinghouse or hotel. Such a life could be just as respectable as residence in a private house. In 1879, Sala noted that American married couples lived in fine hotels "by the half-dozen years together." Young married couples made up the mainstay of the guests in many expensive hotels, and teenage wives became the most numerous female residents.[16] At least until the 1890s, young well-to-do and middle-income brides often relied heavily on hotel so-

ciability. In a time when the median age for women at marriage was twenty-two to twenty-four years, younger brides could move into a hotel and enjoy the familiar routine of courting days and the company of young friends. They could spend a major part of their days visiting one another in their rooms or in the public parlors, either mimicking the formal visiting of residential neighborhoods or merely gossiping. According to the social historian Robert Elno McGlone, the conviviality of hotel life relieved women's fears of "early fading" or being "laid upon the shelf," phenomena they saw in many hardworking young wives and mothers who toiled at keeping house. For wives whose husbands traveled a great deal, hotel sociability also made life less lonesome than life alone in a house or an apartment.[17]

Young couples or single people—especially those accustomed to a high standard of living in their parents' homes—could more easily match or improve those standards by living in a palace hotel or midpriced hotel than by buying the expensive furnishings for a private house. Up to the 1890s, there were apartments for the very rich but a less ready supply of socially respectable apartments geared to middle incomes. Hotel managers catered to these desires for an impressive domicile; the plush furnishings in a good midpriced hotel could cost about half as much as the building itself. A traveler in 1855 observed that the better boardinghouses and almost all hotels were "furnished in a far more costly manner than a majority of young men can afford"—in fact, a life-style that would have cost twice as much in an individual household. This continued to be true into the 1920s. In 1926, a conservative estimate for the cost of complete furnishings for a professional person's household, with no servant and only an upright piano as an extravagance, totaled $5,000.[18] Such an initial cost, spread out in monthly rentals, bought far more sumptuous surroundings in a hotel.

Monthly rental costs in a midpriced hotel were usually one-half to one-third the rates at palace hotels. A Chicago sociologist, Norman Hayner, compared costs in the mid-1920s and found that a single room with bath at a midpriced hotel usually ranged from $40 to $60 a month. Hotel managers almost never advertised or divulged monthly rents charged to tenants, since they were individually negotiated. For permanent guests, monthly rates were always less than four times the weekly rate; sometimes they were only two weeks' rent for a month of occupancy.[19] For single people who did not have a servant or a family

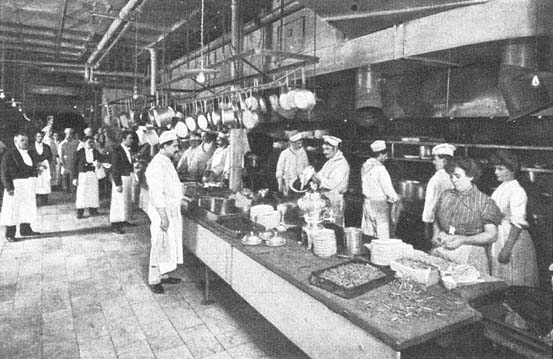

Figure 3.4

The core of cooperative housekeeping. A hotel's kitchen and serving staff pictured in Cosmopolitan

in 1905.

member to perform food preparation and housework, these prices were a bargain. As late as 1909, social workers admitted that it "nearly always" cost more "time, effort, and money to live well in suburbs than in town." Three Chicago schoolteachers explained to Hayner that separately they had been paying $6 or more per week for rooms with individual families. By pooling their rent money for a large room in an elegant midpriced hotel, they each saved a dollar a week and lived far more conveniently and convivially.[20]