Wealthy Hotel Dwellers

In palace hotel life, one most often met first-or second-generation wealth—newly successful entrepreneurs in retail, investment, industrial, or mining enterprises. In Chicago's Sherman House in the 1850s lived Marshall Field's partner Levi Z. Leiter and Potter Palmer. Two prominent tenants in an 1869 apartment hotel in Boston were Major and Mrs. Henry Lee Higginson. Major Higginson was a prominent banker as well as the founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In 1874, he moved to his own apartment hotel, the Hotel Agassiz.[16] The families of many of the 1870s leaders of San Francisco's Merchant's Exchange lived in hotels; the exchange was the center of western America's business life.

Predictably, the social groups living at different hotels developed distinct reputations. The eccentric San Francisco philanthropist James Lick, a piano manufacturer who made a fortune in real estate, built the Lick House that later intrigued Twain. In the 1860s, Lick declined to decorate his hotel with the usual buxom female nudes and instead displayed cartloads of tranquil mountain scenes by Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Hill. Thereby, he helped establish the Lick House as the city's preeminently proper family hotel, the home of the "Lick House set." Lick lived out his years at his own elegant hotel, adding his personal reputation and presence to attract others of his economic rank.[17] By the 1890s, the highest prestige in San Francisco had shifted from the Lick

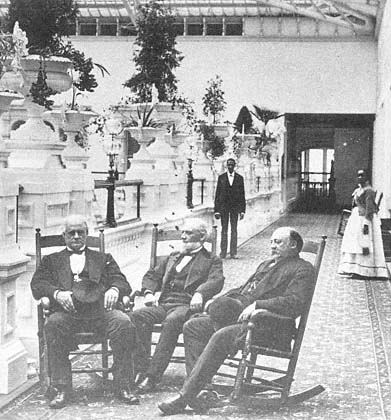

Figure 2.5

Lloyd Tevis, president of Wells Fargo Bank, with friends and servants on the

top floor of the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, ca. 1880.

House to the Palace Hotel. Dozens of California's leading families filled the suites on the top two floors of the hotel, including former Governor Leland Stanford, the president of Wells Fargo Bank, and the editor of one of the city's foremost newspapers and his wife (fig. 2.5). After 1910, the residents of the St. Francis Hotel developed a reputation for being the fashion setters and high rollers, while the Palace residents became known as the more traditional and respectable group.[18]

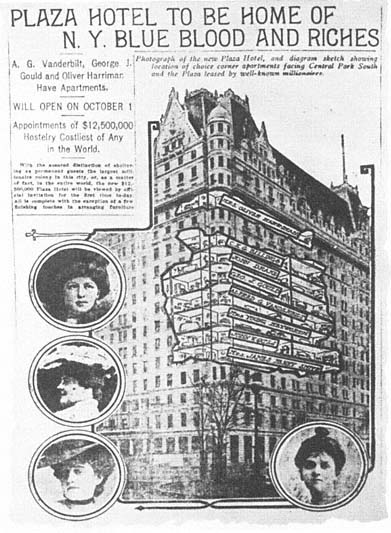

So many business leaders lived in hotels that some developed appropriate corporate legends. In New York City, John W. Gates hammered together the organization of U.S. Steel in his suite at the old Waldorf-Astoria, where he was one of the first permanent guests. James R. Keene, Charles M. Schwab, and other top Carnegie associates also lived at the old Waldorf. When the new Plaza Hotel opened in 1907, the New York Times printed a cutaway diagram of the hotel, revealing the corner suites of the most prominent residents, representing among them many of America's most famous fortunes (fig. 2.6). John Gates

Figure 2.6

Newspaper diagram of the Plaza Hotel, 1907. Published just before the

hotel opened, this cutaway view shows where the wealthiest families

were to live.

and his wife were on the list, along with Mr. and Mrs. George J. Gould, Mr. and Mrs. Alfred G. Vanderbilt, and Mrs. Oliver Harriman.[19]

These most famous and wealthy hotel tenants probably moved to hotels largely for convenience. However, every famous and influential hotel resident attracted a dozen other people like the Spraggs, people who needed to know and be seen with the dominant social group of the city and nation. Indeed, the palace hotel was an important residential counterpart to the increasingly national and closely linked social group leading American business. The rapidly expanding size of corporations and the sheer number of large business organizations after 1900 meant a marked expansion in the number of highly paid and

fairly mobile white-collar employees. Developers made ample provisions in the new palace hotels for this infusion of investors, lawyers, bankers, brokers, financial analysts, and other professionals looking for expensive residential hotel rooms. In 1910, for instance, Tessie Fair Oelrichs, the daughter of the mining king James Fair, completed the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. On opening, half of the rooms were reserved for permanent guests who needed a downtown pied-à-terre. This level of demand was repeated sixteen years later when the Mark Hopkins opened directly across the street from the Fairmont.[20]