Convenient Luxury

At the most practical level, wealthy people loved hotel life because it eliminated the routine responsibilities of managing a large house and garden, devising details for the constant round of dinner parties and elaborate family meals, and supervising an often un-

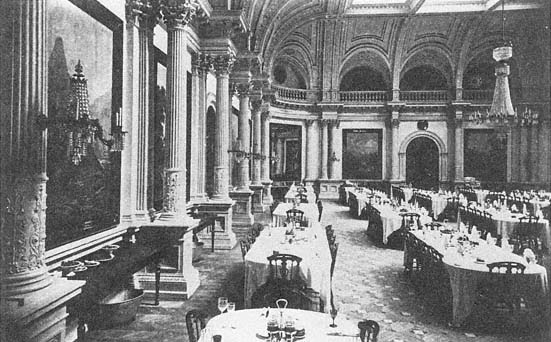

Figure 2.2

The dining room of the Lick House in San Francisco, built in 1861. Until the 1940s, dining areas remained

the chief social vortex of palace hotel life.

ruly staff of servants. Beginning in the 1870s, middle and upper class Americans in private houses (especially the women of the houses) complained regularly about the "servant problem." The available servants were ill-trained, prone to move often, expensive, and not nearly so docile as servants in England. From the 1890s to 1920, the problems increased as immigration brought fewer domestic workers from northern Europe. In the face of these problems, hotels promised perfected service 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. "A suite at the luxurious Westward Ho! will solve all your housekeeping problems," chirped a typical hotel advertisement in the decade before World War I. "We're glad to do your hiring and firing."[3]

Hotel life also offered a gregarious existence not possible in private houses. Grand hotels were built for crowds, and hotel life was spectacularly and notoriously public. In an expensive hotel, barrooms concentrated political and business life; dining rooms, social life.[4] San Francisco's Lick House featured a dining room one hundred feet on a side; the long tables could seat four hundred people amid decor modeled after the dining hall of Versailles (fig. 2.2). The dining room of a palace hotel usually outshone all the other public spaces except the lobby. Before the Civil War, servants sounded great gongs to announce

Figure 2.3

Dinner menu from the exclusive Royal Poinciana Hotel in Palm

Beach, Florida, 1900.

the beginning of the serving hours, which extended for several hours for each meal. Guests walked in during the first half hour, sat down with other people at unreserved tables, and ordered dishes from the day's long bill of fare (fig. 2.3). The American plan of hotel pricing combined room costs and four meals a day into a single daily price. As late as 1910, most of the best hotels were strictly on the American plan.[5]

Astute observers explained the popularity of hotel dining—and hotel living in general—as a manifestation of a peculiarly sociable and gregarious American spirit. In England during the mid-nineteenth century, upper-class hotel guests usually ate alone in private hotel dining rooms. In 1844, when a New York hotel offered this service for the first time in the United States, a local editor objected to the idea as "directly opposed to American ideals of democracy." The public experiences in hotel dining rooms and drawing rooms, he continued, were the "tangible

republic"; "going to the Astor and dining with two hundred well-dressed people and sitting in a splendid drawing room with plenty of company" were major charms of urban life. He warned that private dining in hotels "engendered the spread of dangerous blue-blood habits."[6]

The convenience and sociability of hotel dining aside, pre-Civil War cooking in palace hotels was not always inviting. After spending most of 1862 in America's elegant hotels, the English writer Anthony Trollope praised the vast quantities and types of food served but dreaded the sight of the "horrid little oval dishes" in which all the food swam in grease.[7] After the Civil War, palace hotel managers increased the use of fine cooking to distinguish their hostelries. They imported the best chefs, offered elaborate and exotic menus, and initiated more socially stratified seating procedures in their dining rooms. After 1870, new guests had to know the maître d' (or buy his attention) to get a prominent table, and the tables were no longer of mixed parties. In most cities by 1900, three of the top five restaurants were sure to be in palace hotels, and the creative cookery and inventive bar drinks of the era often emanated from hotel chefs or hotel barkeepers. Parker House rolls, Waldorf salad, Maxwell House coffee, and the Manhattan cocktail all gained their names from hotels. The importance of dining in the company of an elegant crowd and fine food continued into the twentieth century, although elite Americans were building more privacy and class separation into their environments (fig. 2.4). In the 1930s, for instance, a group of New York millionaire investors wanted to have residential suites in a hotel whose restaurant would match the quality of chef Charles Pierre's Park Avenue restaurant. They backed the chef in building the forty-two-story Hotel Pierre.[8]

As Wharton's Spragg family found, palace hotels offered their greatest advantage in the commercialized and nearly instant social position they conferred on their residents. Tenants at palace hotels bought status rather than waiting for it to accrue. Hotel life did not require the slow building and furnishing of an expensive house in the correct neighborhood, the gradual building up of a reputation, or the laborious wheedling of one's way into the proper social clubs and dinner circuits. Immediately after moving into a palace hotel, newcomers could begin to observe (and be observed by) the local elite. The revelry of upper-class dances, banquets, and weddings provided still more social stimu-

Figure 2.4

The Old Poodle Dog Restaurant in San Francisco, an elegant restaurant that competed with palace hotel

dining before 1920.

lation and opportunity. "The pleasantest parties in the world are given at the Lick House," wrote Mark Twain in 1864, further noting that scarcely any save the guests of the establishment were invited.[9] For over a hundred years, hotel advertisers reminded readers that their ballrooms were the scene of particular "invitational dances of the inner circle of society," or they featured photographs of their entertaining rooms to emphasize the hotel's central position in society rituals.[10]

Although the public rooms of a hotel harbored a gregarious life, once residents left the ground floor they could arrange for absolute privacy. As one guest put it, "One of the great joys of being in a hotel" was "to be alone and to be left alone."[11] Desk clerks screened visitors, salesmen, community fund solicitors, and journalists. The service hallways allowed politicians or stage personalities to evade public contact. The better the hotel, the heavier were its walls and draperies and the better the acoustical isolation of its rooms. The selectivity of hotel privacy was its advantage over other private realms. One could intersperse days or hours of seclusion with the conviviality of the dining room, lobby, bar, or downtown theater, gymnasium, or club. "A distinguished literary person can be as isolated in a hotel room as in a cabin in the north woods," wrote one observer, "and yet meet and talk with people at will." At some points in their careers, he added, many prominent busi-

ness people, scientists, artists, writers, and editors relied on hotel seclusion to meet deadlines in their work.[12]

For the very wealthy, a handsome suite in the best hotel cost only a fraction of the price for maintaining a mansion or large private house with comparable amenities. In 1870 in one of San Francisco's five best hotels, a suite of rooms and food cost about $1,000 a year, or $19 a week.[13] By the 1920s, the peak decade for living in hotels, a single room and bath cost from $100 to $230 a month for rent only. Special service and food were available for additional fees. (The usual palace resident rented at least a two-room suite; the single-room price is given here for comparison with other hotel types.)[14] These prices, too, were considerably less than the cost of keeping up a large house with servants (See table 2, Appendix).[15] The generally expanding and volatile business climate of the United States generated both the incomes that paid these costs and also the people who chose hotel life.