Personal Ease and Instant Social Position

In 1836, just before the famous Astor House opened in New York, Horace Greeley's New Yorker said, "We hear that half the rooms are already engaged by families who give up housekeeping on account of the present enormous rents of the city."[2] In 1926, when the Mark

Figure 2.1

The Plaza Hotel, New York City, opened in 1907 on a dramatic site

overlooking Fifth Avenue mansions and the corner of Central Park.

It epitomized the social and practical advantages of palace-rank hotel life.

Hopkins opened in San Francisco, high rents for private houses and the social prestige of hotel life were still attracting permanent hotel guests in high numbers. On opening, half of the Mark Hopkins rooms had been leased by permanent guests. At palace hotels the truly wealthy enjoyed perfected personal service, superior dining, sociability as well as privacy, physical luxury, and instant status—all at a cost lower than keeping a mansion or large house. Through palace hotel life, nouveaux riches could buy reliable entry to high society; similarly, through hotel life those already at social pinnacles could maintain their position.

Convenient Luxury

At the most practical level, wealthy people loved hotel life because it eliminated the routine responsibilities of managing a large house and garden, devising details for the constant round of dinner parties and elaborate family meals, and supervising an often un-

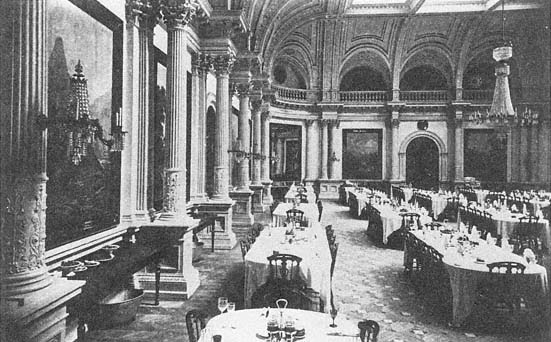

Figure 2.2

The dining room of the Lick House in San Francisco, built in 1861. Until the 1940s, dining areas remained

the chief social vortex of palace hotel life.

ruly staff of servants. Beginning in the 1870s, middle and upper class Americans in private houses (especially the women of the houses) complained regularly about the "servant problem." The available servants were ill-trained, prone to move often, expensive, and not nearly so docile as servants in England. From the 1890s to 1920, the problems increased as immigration brought fewer domestic workers from northern Europe. In the face of these problems, hotels promised perfected service 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. "A suite at the luxurious Westward Ho! will solve all your housekeeping problems," chirped a typical hotel advertisement in the decade before World War I. "We're glad to do your hiring and firing."[3]

Hotel life also offered a gregarious existence not possible in private houses. Grand hotels were built for crowds, and hotel life was spectacularly and notoriously public. In an expensive hotel, barrooms concentrated political and business life; dining rooms, social life.[4] San Francisco's Lick House featured a dining room one hundred feet on a side; the long tables could seat four hundred people amid decor modeled after the dining hall of Versailles (fig. 2.2). The dining room of a palace hotel usually outshone all the other public spaces except the lobby. Before the Civil War, servants sounded great gongs to announce

Figure 2.3

Dinner menu from the exclusive Royal Poinciana Hotel in Palm

Beach, Florida, 1900.

the beginning of the serving hours, which extended for several hours for each meal. Guests walked in during the first half hour, sat down with other people at unreserved tables, and ordered dishes from the day's long bill of fare (fig. 2.3). The American plan of hotel pricing combined room costs and four meals a day into a single daily price. As late as 1910, most of the best hotels were strictly on the American plan.[5]

Astute observers explained the popularity of hotel dining—and hotel living in general—as a manifestation of a peculiarly sociable and gregarious American spirit. In England during the mid-nineteenth century, upper-class hotel guests usually ate alone in private hotel dining rooms. In 1844, when a New York hotel offered this service for the first time in the United States, a local editor objected to the idea as "directly opposed to American ideals of democracy." The public experiences in hotel dining rooms and drawing rooms, he continued, were the "tangible

republic"; "going to the Astor and dining with two hundred well-dressed people and sitting in a splendid drawing room with plenty of company" were major charms of urban life. He warned that private dining in hotels "engendered the spread of dangerous blue-blood habits."[6]

The convenience and sociability of hotel dining aside, pre-Civil War cooking in palace hotels was not always inviting. After spending most of 1862 in America's elegant hotels, the English writer Anthony Trollope praised the vast quantities and types of food served but dreaded the sight of the "horrid little oval dishes" in which all the food swam in grease.[7] After the Civil War, palace hotel managers increased the use of fine cooking to distinguish their hostelries. They imported the best chefs, offered elaborate and exotic menus, and initiated more socially stratified seating procedures in their dining rooms. After 1870, new guests had to know the maître d' (or buy his attention) to get a prominent table, and the tables were no longer of mixed parties. In most cities by 1900, three of the top five restaurants were sure to be in palace hotels, and the creative cookery and inventive bar drinks of the era often emanated from hotel chefs or hotel barkeepers. Parker House rolls, Waldorf salad, Maxwell House coffee, and the Manhattan cocktail all gained their names from hotels. The importance of dining in the company of an elegant crowd and fine food continued into the twentieth century, although elite Americans were building more privacy and class separation into their environments (fig. 2.4). In the 1930s, for instance, a group of New York millionaire investors wanted to have residential suites in a hotel whose restaurant would match the quality of chef Charles Pierre's Park Avenue restaurant. They backed the chef in building the forty-two-story Hotel Pierre.[8]

As Wharton's Spragg family found, palace hotels offered their greatest advantage in the commercialized and nearly instant social position they conferred on their residents. Tenants at palace hotels bought status rather than waiting for it to accrue. Hotel life did not require the slow building and furnishing of an expensive house in the correct neighborhood, the gradual building up of a reputation, or the laborious wheedling of one's way into the proper social clubs and dinner circuits. Immediately after moving into a palace hotel, newcomers could begin to observe (and be observed by) the local elite. The revelry of upper-class dances, banquets, and weddings provided still more social stimu-

Figure 2.4

The Old Poodle Dog Restaurant in San Francisco, an elegant restaurant that competed with palace hotel

dining before 1920.

lation and opportunity. "The pleasantest parties in the world are given at the Lick House," wrote Mark Twain in 1864, further noting that scarcely any save the guests of the establishment were invited.[9] For over a hundred years, hotel advertisers reminded readers that their ballrooms were the scene of particular "invitational dances of the inner circle of society," or they featured photographs of their entertaining rooms to emphasize the hotel's central position in society rituals.[10]

Although the public rooms of a hotel harbored a gregarious life, once residents left the ground floor they could arrange for absolute privacy. As one guest put it, "One of the great joys of being in a hotel" was "to be alone and to be left alone."[11] Desk clerks screened visitors, salesmen, community fund solicitors, and journalists. The service hallways allowed politicians or stage personalities to evade public contact. The better the hotel, the heavier were its walls and draperies and the better the acoustical isolation of its rooms. The selectivity of hotel privacy was its advantage over other private realms. One could intersperse days or hours of seclusion with the conviviality of the dining room, lobby, bar, or downtown theater, gymnasium, or club. "A distinguished literary person can be as isolated in a hotel room as in a cabin in the north woods," wrote one observer, "and yet meet and talk with people at will." At some points in their careers, he added, many prominent busi-

ness people, scientists, artists, writers, and editors relied on hotel seclusion to meet deadlines in their work.[12]

For the very wealthy, a handsome suite in the best hotel cost only a fraction of the price for maintaining a mansion or large private house with comparable amenities. In 1870 in one of San Francisco's five best hotels, a suite of rooms and food cost about $1,000 a year, or $19 a week.[13] By the 1920s, the peak decade for living in hotels, a single room and bath cost from $100 to $230 a month for rent only. Special service and food were available for additional fees. (The usual palace resident rented at least a two-room suite; the single-room price is given here for comparison with other hotel types.)[14] These prices, too, were considerably less than the cost of keeping up a large house with servants (See table 2, Appendix).[15] The generally expanding and volatile business climate of the United States generated both the incomes that paid these costs and also the people who chose hotel life.

Wealthy Hotel Dwellers

In palace hotel life, one most often met first-or second-generation wealth—newly successful entrepreneurs in retail, investment, industrial, or mining enterprises. In Chicago's Sherman House in the 1850s lived Marshall Field's partner Levi Z. Leiter and Potter Palmer. Two prominent tenants in an 1869 apartment hotel in Boston were Major and Mrs. Henry Lee Higginson. Major Higginson was a prominent banker as well as the founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. In 1874, he moved to his own apartment hotel, the Hotel Agassiz.[16] The families of many of the 1870s leaders of San Francisco's Merchant's Exchange lived in hotels; the exchange was the center of western America's business life.

Predictably, the social groups living at different hotels developed distinct reputations. The eccentric San Francisco philanthropist James Lick, a piano manufacturer who made a fortune in real estate, built the Lick House that later intrigued Twain. In the 1860s, Lick declined to decorate his hotel with the usual buxom female nudes and instead displayed cartloads of tranquil mountain scenes by Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Hill. Thereby, he helped establish the Lick House as the city's preeminently proper family hotel, the home of the "Lick House set." Lick lived out his years at his own elegant hotel, adding his personal reputation and presence to attract others of his economic rank.[17] By the 1890s, the highest prestige in San Francisco had shifted from the Lick

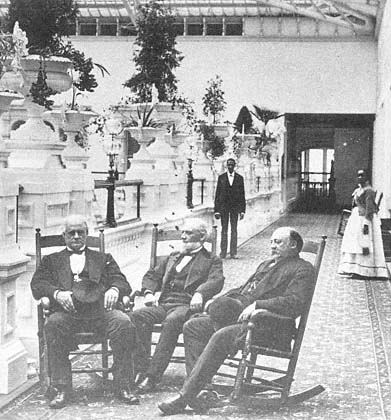

Figure 2.5

Lloyd Tevis, president of Wells Fargo Bank, with friends and servants on the

top floor of the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, ca. 1880.

House to the Palace Hotel. Dozens of California's leading families filled the suites on the top two floors of the hotel, including former Governor Leland Stanford, the president of Wells Fargo Bank, and the editor of one of the city's foremost newspapers and his wife (fig. 2.5). After 1910, the residents of the St. Francis Hotel developed a reputation for being the fashion setters and high rollers, while the Palace residents became known as the more traditional and respectable group.[18]

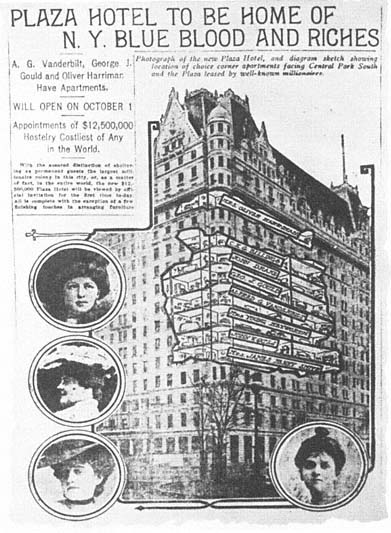

So many business leaders lived in hotels that some developed appropriate corporate legends. In New York City, John W. Gates hammered together the organization of U.S. Steel in his suite at the old Waldorf-Astoria, where he was one of the first permanent guests. James R. Keene, Charles M. Schwab, and other top Carnegie associates also lived at the old Waldorf. When the new Plaza Hotel opened in 1907, the New York Times printed a cutaway diagram of the hotel, revealing the corner suites of the most prominent residents, representing among them many of America's most famous fortunes (fig. 2.6). John Gates

Figure 2.6

Newspaper diagram of the Plaza Hotel, 1907. Published just before the

hotel opened, this cutaway view shows where the wealthiest families

were to live.

and his wife were on the list, along with Mr. and Mrs. George J. Gould, Mr. and Mrs. Alfred G. Vanderbilt, and Mrs. Oliver Harriman.[19]

These most famous and wealthy hotel tenants probably moved to hotels largely for convenience. However, every famous and influential hotel resident attracted a dozen other people like the Spraggs, people who needed to know and be seen with the dominant social group of the city and nation. Indeed, the palace hotel was an important residential counterpart to the increasingly national and closely linked social group leading American business. The rapidly expanding size of corporations and the sheer number of large business organizations after 1900 meant a marked expansion in the number of highly paid and

fairly mobile white-collar employees. Developers made ample provisions in the new palace hotels for this infusion of investors, lawyers, bankers, brokers, financial analysts, and other professionals looking for expensive residential hotel rooms. In 1910, for instance, Tessie Fair Oelrichs, the daughter of the mining king James Fair, completed the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. On opening, half of the rooms were reserved for permanent guests who needed a downtown pied-à-terre. This level of demand was repeated sixteen years later when the Mark Hopkins opened directly across the street from the Fairmont.[20]

Hotel Children

Since married couples (particularly young married couples) often lived in palace hotels, children were a prominent part of residential hotel life, especially in the nineteenth century. The wealthier the young family (with either one parent or both parents present), the more likely they were to have children with them. In 1880, 114 out of the 225 permanent guests in the Lick House were families: 15 married couples with no children, 12 couples with one child, and 9 families with two or more children. One family had five children.[21] When Twain lived at the Lick House, he learned to detest the younger children there, and he explained his judgment by describing a typical afternoon as he tried to work in his room:

Here come those young savages again—those noisy and inevitable children. God be with them!—or they with him, rather, if it be not asking too much. . . . I know there are not more than 30 or 40 of them, yet they are under no sort of discipline, and they make noise enough for a thousand. . . . They assault my works [the door to his room]—they try to carry my position by storm—they finally draw off with boisterous cheers, to harass a handful of skirmishes thrown out by the enemy—a bevy of chambermaids.[22]

In Twain's account, the chambermaids abandon their brooms. The children, still without supervision, ride the brooms as horses and return to taunt the author. Next they attack a Chinese laundryman, steal his basket, and pull his queue. Finally, the children's nurses arrive and drag them off, to Twain's relief.

Twain was hardly alone in his exasperation. "Close and frequent acquaintance with small juveniles in an American hotel," wrote the London journalist George Augustus Sala in 1879, "is apt to induce the conviction that, all things considered, you would like the American child

best in a pie."[23] Victorian hotel rules expressly prohibited the conversion of corridors into playgrounds, but besides the children's dining room, youngsters had few other places to go. In the 1890s, in keeping with new attitudes about children's spaces in American homes, the managers of large hotels began to install kindergartens, playrooms, special classes, and other organized children's programs. The huge McAlpin Hotel in New York had an entire floor set aside for women and children—for both transient and permanent guests.[24]

By the late 1920s, with the greater expansion of apartment living and suburban housing options, the demand for raising children in hotels declined. Only a few palace hotels had so many young children, and some allowed no young children at all. In 1929, for instance, all the 160 permanent residents of San Francisco's Canterbury Hotel were listed in the social register. There were 94 single people (single women outnumbering single men by about 4 to 1), 27 couples with no children, and only 6 families with children.[25] Yet in 1955, Kay Thompson could still choose New York's Plaza Hotel as the setting for a children's book with a rambunctious heroine named Eloise who terrorizes the lobby, elevators, empty meeting rooms, and corridors. Eloise epitomizes the pampered, privileged, upper-class hotel child: she is six years old, with a tutor who goes to Andover, a full-time English nanny, and precocious knowledge of how to order anything she wants from room service. She also divulges that her mother is thirty years old, has a charge account at Bergdorf's, knows the hotel owner ("and Coco Chanel and a dean at Andover, too"), and travels a great deal.[26] At age six, Eloise is well entrained in an upper-class trajectory, and her mother is apparently maintaining her own class status as well.

Edmund White gives a less glowing account of growing up in a "luxury hotel, sedate and respectable," at about the same time as Eloise. White's mother apparently chose the best possible hotel to meet the kind of new husband who could improve her shaky financial status. She could afford only one room with twin beds; White and his sister took turns sleeping on the floor. His mother was gone most of the time, and on cold days the children morosely hung around the hotel, picking fights with each other and eating at different times to avoid each other in the dining room. White discovered an accessible parapet off the empty ballroom and spent hours there, reading.[27]

Especially after 1930, hotel children like Eloise and White had few playmates because outside children were afraid of hotels. For adventure and companionship hotel children often tagged along with the chambermaids and bellboys on their rounds, learning all the inside gossip about the guests. Conscientious mothers complained that they had more child-care responsibilities in hotels compared to houses, because in hotels it was harder to keep children happy.[28] Indeed, the hotel emphasized adult social needs, in contrast to the child-centered suburban environment.

The children in hotels may not have cared much about architectural opulence, but adult hotel residents certainly did. Like the commercial sociability and other personal advantages of hotel life, architectural luxury and geographic prominence of palace hotels were important attributes for the class formation aspects of expensive hotel life.