Expanding the Notion of Home

The history of hotel life shows that the crisis in the residential hotel supply was a planned event. So too, solutions to the SRO crisis can be planned events choreographed by residents, activists, officials, owners, and experts. Pioneering groups have begun to build new residential hotels, thereby stretching the boundaries of both the official and public definitions of home in America.

The new residential hotel building types are as varied as their different sites and cities. For lower-income residents, hotel makers are reinventing the rooming house; higher-income residents are seeing variations on the midpriced hotel or motel. For new rooming houses, the trend is to plan fairly large buildings with at least one hundred rooms. Most typically, they are structures remodeled or built with some type of public/private partnership and managed by a nonprofit organization. However, with initial subsidies a few private developers have also successfully developed SRO projects. Because neighborhoods at the edges of town continue to block efforts to build for a diverse population, these hotels continue to be on expensive downtown land. Like the downtown rooming houses of 1910, the new rooming houses rely on commercial rentals on their ground floor to subsidize rents on the upper floors and to provide retail services for a neighborhood where home activities are scattered up and down the street. The new rooming

Figure 9.16

First floor plan for San Diego's Baltic Inn, opened in 1987. Rooms at the lower

part of the plan include the lobby, manager's apartment, and service spaces.

houses require larger lots to accommodate a comparatively large number of parking spaces—more than the 1910 rooming house, which had no parking spaces, and fewer than the typical present apartment requirement of one parking space per unit.

In the early 1990s, about a dozen of these projects in the United States are either newly built or in working drawings. Two West Coast examples are typical. In San Diego, California, the 207-room Baltic Inn opened in 1987. It was the first new SRO building in the city in seventy years and one of the first in the nation (figs. 9.16, 9.17). It marks a new least-expensive version of the rooming house. As one commentator characterized the legal permit battles for the hotel, "San Diego has said, in effect, that it is willing to permit some citizens to live in places most others would not prefer."[63] In Berkeley, California, the Studio Durant project has been planned for a large lot between the city's downtown retail district and the University of California campus. The 198 rooms occupy the upper three floors. At the back of the site (with an E-shaped plan of rooms above) is a large parking area; retail spaces and a generous lobby fill the site next to the sidewalk. The project features timely commercial facade design, as any good hotel owner would have re-

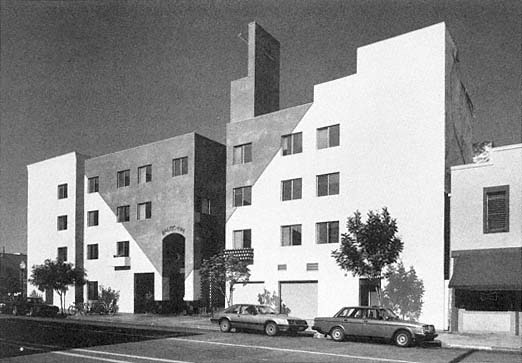

Figure 9.17

Street view of the new Baltic Inn, San Diego.

quired in the past (fig. 9.18). The projected construction cost in 1991, $20,000 a room, compares favorably with the $27,000 a room being spent to renovate a residential hotel across town.[64]

The most striking physical changes in these new rooming house buildings include their provision of more social spaces—lobbies, lounges, and shared kitchens—and their improved ratio of baths to rooms. The one to six ratio from 1910 is no longer viable. The Baltic Inn provides the new minimum: a private toilet for each room, simply in a stall behind a curtain, and a room sink on a small all-purpose countertop area. Showers are down the hall. The plan for the Studio Durant, geared to a slightly higher rent, provides each very small room with a private shower and toilet room and a room sink on a longer all-purpose counter built as a cooking area (with a small refrigerator and a microwave oven as standard equipment). The bathroom sink doubling as the kitchen sink harks back to light housekeeping rooms of the 1940s. The tiny built-in kitchen area, which has yet to gain a name, does not make these new dwellings into full studio apartments; in most cases these structures are not designed to meet apartment building codes. Instead, the better plumbing and wiring, the rudimentary baths and cooking

Figure 9.18

Perspective view of the Studio Durant, a new rooming house planned for downtown Berkeley, California.

The architect, David Baker, expresses each of the functional elements on the facade of the project.

units, are responses to age-old demands from both hotel residents and managers. In the past, because the wiring was not adequate, the smells disturbed neighbors, or the food attracted vermin, managers even in palace and midpriced hotels fought tenants who illegally cooked in their rooms. However, the small inexpensive refrigerator has revolutionized food storage. Milk bottles set to keep cool overnight on rooming house window ledges are no longer a telltale sign of residents making breakfasts in their rooms, and vermin can be made less prevalent as well. Making the wiring, plumbing, and cabinetwork more adequate from the beginning is better for both tenants and managers. The increase in bath ratio is completely in keeping with the history of increasing plumbing expectations in dwellings of all sorts in the United States.

Sustaining existing residential hotel buildings continues to be essential and even more challenging than constructing new buildings. Because very few purpose-built rooming houses were constructed after the early 1920s, 99 percent of the inexpensive hotel rooms in the United States are in structures that are seventy years old or more. Their heating systems and elevators wore out long ago, and most have been inexpertly patched and repaired rather than replaced. If the buildings have

any cooling system at all, it probably consists of those few windows that still operate. The plumbing is as old as the heating; the plumbing ratio usually needs to be improved, at least to one bath for each four rooms. All this refitting has to be done inexpensively and if possible without closing the building entirely. In 1990, using Community Redevelopment Agency funds, advocates in Los Angeles opened 520 newly rehabilitated SRO rooms on skid row and planned to build a new 72-room hotel. The sponsors argue that these SRO services will cost the city $11 a night versus the $28 per night for ward-style shelters. San Francisco has bought and renovated six hotels (with a total of 460 rooms) and turned them over to nonprofit agencies for management. In 1991, the city's Redevelopment Agency—the former archenemy of residential hotels—remodeled a downtown building as mixed apartments and SRO units. The unsung heroes of the hotel housing movement include the architects, managers, and financial backers who devise ways to upgrade structures like these.

Rehabilitated structures provide the widest variation in size and social program. Sheltered dwellings, small board-and-care homes, and halfway houses have made use of modest structures in a variety of settings, even in outlying single-family neighborhoods. In the 1990s, market rents marginally sustain thousands of 30-room downtown rooming houses, anonymous three-story buildings on 25-foot-wide lots often managed by families of recent immigrants. With appropriate subsidies for maintenance, these structures can continue to provide housing, probably at the upper end of the SRO price range. Midsized buildings, from 30 to 80 rooms, are more expensive to buy and manage; most hotel activists say that roughly 100 rooms are needed to make efficient use of a full-time manager and to staff a desk 24 hours a day. The scale of a 100- to 150-room older structure is also well matched to the financial abilities of many nonprofit organizations. The largest inexpensive hotels—those with 400 rooms—often require different sorts of organizations or partnerships for purchase, rehabilitation, and management.

Hotels that fewer people want to talk about are new or rebuilt temporary shelters for people living on the streets or in their cars. These structures may have to be the future equivalents of the lodging house rank—the dormitories, cubicles, and missions from the Progressive Era. They could replace the hastily converted armories, church base-

ments, barely renovated flophouses, and other temporary shelters that have become quasi-permanent while the SRO crisis has intensified. As temporary shelters or as permanent single-room housing, hotels cannot solve the entire housing crisis. But they can help to solve parts of it, especially for single men and women (even some with children) who need to get off the streets, for single working people with low incomes, and for low-income elderly people.

A possible revival is apparent for hotels at more expensive levels, too. Private developers in Quincy, Massachusetts, opened a new sixteenunit rooming house in 1986, the first purpose-built rooming house constructed in the Boston area in several decades. All over the United States, both public and private developers have reinvented the role of the midpriced hotel in the form of elderly housing developments with household services and common meals. In 1990, one typical Bay Area "retirement hotel" offered a private room, full hotel services, and meals for $1,500 a month and shared rooms for $650 a month. Chains of Hometels and Embassy Suites have begun to combine motel, hotel, and residential hotel features. For rents of $2,000 a month (without meals), expensive new apartment hotels—including a 44-story example in Chicago—essentially re-create the apartment hotel of the early 1900s.[65] The popular television series "Beverly Hills 90210" featured a teenage hotel child for much of the first season. According to the show's writers, the character of Dylan McKay "was supposed to live in the Beverly Wilshire, like Warren Beatty." Dylan is the Eloise of the Plaza for the 1990s.[66]

New and rehabilitated hotel buildings are only one of the new experimental residential structures that promoters are proposing to the American public. Not since the 1890s have so many new types of units, mixtures of uses, and shared facilities been tried simultaneously in the United States. Live-work (loft) structures, "mingles" (apartments designed to be shared or co-owned by two separate heads of household), co-housing (a cluster of separate houses that share cooking, recreation, child care, and open space), and "doubling up" (two households sharing one house to counteract high rents) are examples of a sudden burst of chosen or forced experimentation.[67] These projects, along with hotels, can reasonably be expected to push into more suburban settings as well.

These experiments continue to spark heated debates and are usually slow to gain official permission. Housing activists repeatedly must climb against a hundred-year-old glacial accumulation of skewed textbooks, laws, bureaucracies, and attendant attitudes. Two years or more can easily go by while the sponsors of a new rooming house debate with their financiers, the local planning office, the zoning commission, and finally the city council over procedural questions and definitions, including: Should each room in the rooming house be required to have a separate off-street parking space? Are these units legally apartments? If they are not apartments, what are they? If the minimum permitted room size is relaxed, what happens in the future? How will the management guarantee that future densities will not soon overwhelm provisions geared to one- or two-person households?

Obviously, funding subsidies are a prerequisite for most hotel housing projects at the lodging house or rooming house level. Public funds for construction and rebuilding of hotel housing are urgent, and they are needed in far larger amounts than ever before spent for alternative housing projects in the United States. Taxpayers who balk at these expenditures must be consistently reminded that, according to one analysis, the 1990s home owner deduction from federal income taxes has amounted each year to a $47 billion subsidy for private suburban households, half with incomes over $80,000 a year. This private home owner deduction equals four times the entire annual budget of the Department of Housing and Urban Development.[68] If the economically comfortable can be so handsomely subsidized, in good times as well as bad, then the economically essential—the poorly paid people or elderly people who have played fundamental roles in our economy but at low-paying jobs—equally deserve subsidy.

Along with funds for construction, new programs must be funded for management training, building on the New York City model. Running a hotel was one of the most demanding jobs of the nineteenth century, and it is still a task that requires more than can be learned on the job. The horrors of past and present street hotels and indifferently managed flophouses have repeatedly proved that management is as important as the building itself for successful hotel housing. The current cadre of nonprofit hotel staff cannot stretch to cover the number of improved hotels that are needed in the near future.

The necessity of hotel housing is not decreasing. All indications from those who know the homeless situation point in one direction: the need for inexpensive, nonapartment housing is only going to increase. Alice Callaghan, from the Skid Row Housing Trust of Los Angeles, noted in 1992 that hotels were still the last place available for urban people. Like so many other SRO activists, she stressed that hotels provide the last viable safety net for housing; if people miss this net, they will either become homeless—literally forced to live on the street—or institutionalized.[69] It is significant and a sign of wider public concern that Callaghan was being interviewed for an airline flight magazine. In 1970, her only audience might have been the readers of a social welfare journal. Even a relatively conservative housing expert can now publicly point to the unattached as being the least well-served people in American housing. Peter Salons, of Hunter College in New York, emphasizes that "homeless people are merely the most visible portion of the unattached who need housing; there are many more." He continues that these people "do not all need apartments; they need rooms ."[70]

Twenty years of the SRO crisis and of determined study and activism have not produced the massive housing program that is needed, but they have set the stage for such a change. Perhaps the most necessary shift is a broader point of view about urban space, a move away from the monolithic one-best-way approach that gained currency in the late nineteenth century.