Rationales for Lodging House Life

For the men and women who lived in cheap lodging houses, the looming advantage was low price. But cheap lodging houses had other advantages. For the indigent elderly, the advantage of ambulatory independence in a central location was particularly prominent. (This was true of other ranks of hotel life as well.) As long as older tenants could walk, they could meet their own needs. California researchers found that elderly residents cherished their independence. Anderson described areas of a few blocks that satisfied all the employment and services needed by former hoboes. A great many of the aged men and women who lived their last years in cheap lodgings lived in grim surroundings. Yet the psychological benefits of maintaining their personal choice and self-reliance seemed to be the most important attractions of staying in hotel housing, just as it is for the elderly in hotel housing today.[66] For workers, cheap hotels and their staff also provided specific stabilizing services. Before 1925, in the heyday of the cheap lodging house districts, men could turn over their summer earnings to the hotel proprietor, who acted as banker and bursar. This ensured that the hobo or sailor would not lose all his money in one first spree.[67]

For the most outcast people—drifters, unemployables, thieves, or prostitutes—rooming houses simply offered a place to be. Technically, state laws required hotel managers to accept any reasonable person for one night, although managers did not have to accept everyone on a weekly or monthly basis. On occasion, however, landlords welcomed

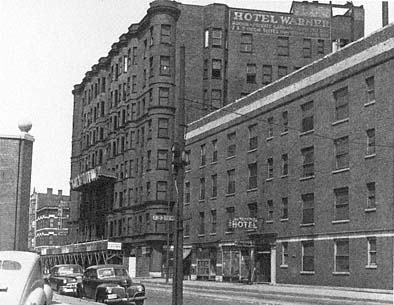

Figure 5.20

Hotels for black workers on Chicago's South Side. The Hotel Warner

and Memorial Hotel on Cottage Grove Street, photographed in 1950.

long-term tenants who were outcasts elsewhere. Poor casual laborers made up a reliable market for slumlords and honest landlords alike. By renting to hoboes, building owners with a warm heart or a dilapidated and unrentable loft space could invest very little money and yet reap a tidy profit. A madam could pay substantially higher leases than other tenants and pay additional sums under the table to the building owner, to district politicians, or to the police. The flophouse floor, even with its vermin, was still a viable commercial space.

The financial pressures on managers who leased cheap hotels probably did the most to open places for outcast people. Each month the lease had to be paid. Only rented rooms brought income. When rooms were going empty, or where the architectural or sanitary conditions were already at a low ebb, undesirable tenants were better than no tenants at all. Managers of "no-tell hotels" that allowed men to take women to their rooms found that they could charge a higher rent. Harvery Zorbaugh asked one hotel keeper how many married couples there were in her house. Her answer: "I don't know—I don't ask. I want to rent my rooms."[68] As long as couples paid, she did not oversee their moral life as old-fashioned boardinghouse keepers might have done. Such management realities, taken to their extreme, fostered the worst social and physical conditions of all types of inexpensive hotels.

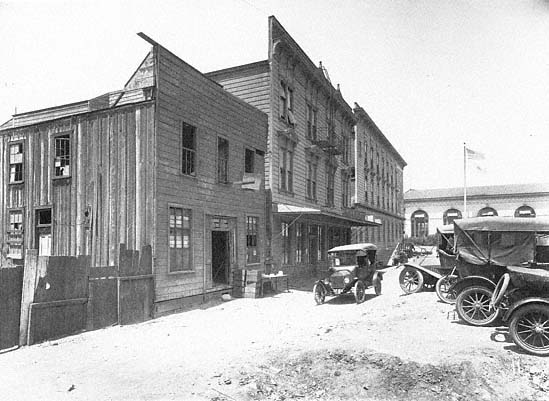

Figure 5.21

Line of wooden rooming houses near the Union Iron Works shipyards in San Francisco, photographed

just before demolition in 1918. The closest building was probably intended to be temporary.

For so-called homeless men, cheap hotels and the area around them were also more than shelter. They were a significant part of hobo identity, just as suburban houses became important for family identity in the middle and upper class. However, unlike suburban houses or better hotels, cheap lodgings were more important as a type of building than as individual structures. The way casual laborers relied on built space contrasted with the manner of the middle and upper class. Wealthy hotel dwellers lived in highly individualistic buildings; their hotel homes were part of an elaborate and individuated material culture system. Midpriced or palace hotel residents could further anchor their identities with their professions, marriage partners, personal pedigrees, and clothes or other possessions. Single laborers, who moved often and easily from one cheap lodging house to another, relied on a more generalized use of the city fabric. They lived largely within a nonmaterialistic and verbal subculture. The social organization and membership in the American day laborer's subculture relied less on unique possessions and more on story telling and social drinking. While less individu-

ally anchored to specific buildings, casual laborers were nonetheless identified with hotels as a group. The anthropologist James Spradley has maintained that flops (places to sleep) made up the most significant set of words in hobo language and culture; no other American group had so many words for places to sleep.[69] Other recent research suggests that, among no-family people, setting in large part can become life-style. The hotels, street corners, parks, and businesses of cheap lodging house districts—even though fluidly used and seen as virtually interchangeable—provided an essential and meaningful backdrop for the single laborers' individual and social worlds. Cheap lodging house districts socially countered the low esteem of hobo employment and provided an island in a hostile dominant society.[70]

Employers and bankers could see advantages to lodging house life, too. The individual freedom of people living completely apart from a family and without material possessions dovetailed precisely with the needs of employers for maximum flexibility and control over a set of workers. The single, more atomized residents of cheap hotels could adjust more easily than family-tied workers to the whimsy of economic demand for a risky new business or a sudden big contract.[71] At a more abstract level of capital circulation, commercial single-room housing had additional benefits for landowners and managers of the middle and upper class. When thousands of workers lived as part of a family or boarded with a family, that rent money went into the family sector; it went back into the control of the private urban community. Hotel life, however, channeled the workers' rent and food money directly into commercial circuits, retail hands, without passing through a private household. More than in family tenement districts, the money of hotel life went into commercial entertainment and commercial socializing. The architecture of the no-family house also displayed these uneasy truces between the renters, the owners, and the employers of the city.