Rooming House Districts:

Diversity and Mixture

In addition to many rooms at low prices, rooming house residents needed at least two other features: easy access to work places, and a surrounding neighborhood with mixed land use including stores, bars, restaurants, and clubs for association with friends and commercial recreation. Few outsiders questioned the first of these two needs. However, the retail mixtures of rooming house neighborhoods caused concern within the dominant culture. They also reinforced the liminal status of rooming house residents.

The Mixtures of Rooming House Streets

Work places and rooming houses were inextricably linked. Especially during boom times, employers needed a ready supply of help on short notice, and workers could afford only so much time and money for their journey to work. Given the erratic availability of employment, they also needed to be within easy reach of many different companies. Roomers rarely owned cars. Thus, rooming house areas were usually within half a mile of varied jobs. For the greatest number of rooming house residents, work was downtown in the retail shopping district in the office core, or in a warehouse, shipping, or manufacturing zone very close to the center of the city. Higher-paid white-collar workers could afford to commute on streetcars to an outlying rooming house area (fig. 4.13). Streetcar transfer locations like these were exceptions to the dominant pattern, but made up between 5 and 10 percent of San Francisco's rooming house supply by 1930.[53]

Rooming houses might have seemed unnecessary to downtown, but they were just as essential for urban economic growth as the family tenements that stretched next to factories and just as basic as the new downtown skyscrapers and loft buildings. At the turn of the century, urban Americans knew at least two different types of rooming house areas: districts of old-house rooming houses, and newer purpose-built rooming house districts.

Figure 4.13

A large outlying rooming house in San Francisco, photographed ca. 1912.

Streetcars to downtown ran directly past the building. Note entrance to hotel

under the small gable roof in the center of the storefronts.

A large central area of San Francisco known as the Western Addition was a quintessential old-house rooming district. Fillmore Street was its commercial and entertainment spine (fig. 4.14).[54] The Western Addition was a twenty-minute walk west of downtown. Between downtown and the Western Addition was a neighborhood of newer flats and houses with higher rents, an area rebuilt after the fire of 1906. Several major streetcar lines crossed the Western Addition on their way farther west to single-family neighborhoods. By the 1920s, Fillmore Street's vaudeville houses, dance halls, and inexpensive restaurants were well known in San Francisco. After the fire, many downtown entrepreneurs had relocated along the street. From the public experience of this main artery, the whole Western Addition was most commonly known as "the Fillmore," although the street itself was off-center, near the edge of the neighborhood (fig. 4.15). Most of the area was filled with former middle-income houses and flats, most built in wood between 1870 and 1900, the later ones using wildly exuberant Victorian ornamentation. Commercial land-use mixture in the Western Addition was common. Owners had built long rows of storefronts into the base of houses or flats and leased them to corner grocery stores, tobacconists, bars, millinery shops, secondhand stores, and antique shops. On the side streets were auto dealers, repair shops, and commercial laundries that stood next to housing and were important employers in the neighborhood (fig. 4.16). Along the major avenues were other employers. At the southeastern corner of the district, the postfire city hall and civic center office complex offered nearby white-collar employment.[55]

Figure 4.14

Map of two principal rooming house districts in

San Francisco. Streets running north and south

(vertically) are, from left to right, Divisadero,

Fillmore, and Van Ness. The diagonal is Market Street.

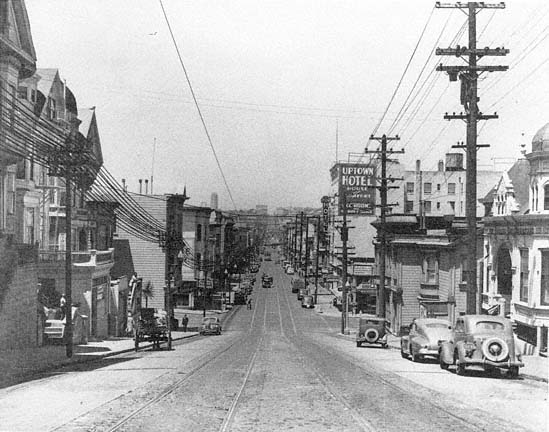

Figure 4.15

Residential section of Fillmore Street in 1944. Seen looking north from Grove Street, this view was

typical of the southern edge of the Western Addition.

Figure 4.16

Side street in the Western Addition in the 1920s. Laundries and industrial shops mixed with

older flats, many rented as rooming houses.

To people from the newer, richer family districts of San Francisco, the streets of the Western Addition epitomized mixture, crude commercialism, and unskilled employment. Many of the commercial building fronts were jerry-built. The housing and commercial spaces were built of wood and rarely faced with masonry, as were the areas closer to downtown. The district represented reuse, the filtering of blocks to new tenants. In the late 1950s, when Alfred Hitchcock looked for an old rooming house setting for a mysterious transitional character in Vertigo , he found what he needed on the southern edge of the Western Addition.[56]

The Western Addition was also known for its social, ethnic, and racial diversity. After the fire, inexpensive rooms of the Western Addition became home for a growing number of German, Russian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants, along with more consolidated settlement patterns of Japanese and African-American families who had been living in dispersed patterns before the fire.[57] At the end of the depression, San Francisco's Real Property Survey documented race on a unit-by-unit basis, showing that at the eastern edge of the Western Addition African-American families were mixed with Japanese, Filipino, and European families. The 1940 census showed that the city's 5,000 blacks

Figure 4.17

Ellis Street in the Tenderloin district, San Francisco, in the early 1940s. Buildings of one-room and

two-room apartments are interspersed next to tall residential hotels.

made up less than 1 percent of the city's population; in the Western Addition, African-Americans comprised 5 percent and by 1960 would comprise half the residents in the area.[58] Most cities had a zone of converted houses with a succession similar to the Western Addition. In Boston, it was the South End; in New York, Chelsea came to be a zone of converted houses; in Chicago, it was the Near North Side.

An adjacent San Francisco area, the Tenderloin district, exemplified another type of rooming precinct—a rebuilt rooming house area that was overwhelmingly white as late as 1970.[59] The Tenderloin is essentially bounded on the west by the Western Addition and on the north by Nob Hill, and it is immediately west of the department stores around Union Square. By the 1920s, most cities had two or three such areas, some of them only a few blocks in extent. Such areas were not composed of old converted houses but new urbane buildings expressly intended as rooming houses, often next to middle-income apartments and midpriced hotels (fig. 4.17). If a single 100-room hotel had represented the social stratification of the hotels in the Tenderloin in 1930, 52 of the rooms would have been of the rooming house type; 26, midpriced; and 22, the cheap lodging house type. The Tenderloin typified a rebuilt rooming house area also in that along one side (the Nob Hill

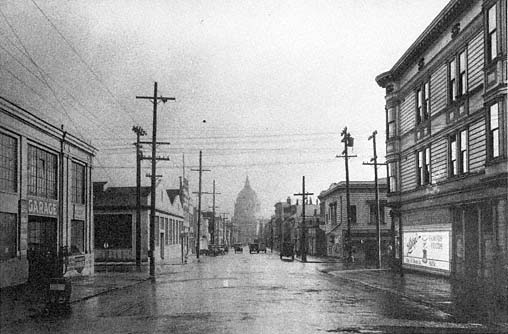

Figure 4.18

The bright light district on Fillmore Street in the 1920s. After the fire of 1906, Fillmore became one of the

substitutes for the burned Market Street. The corner light fixtures added a festival air to the street year-round.

side), it had expensive apartments and houses; and on the opposite side (the South of Market) was a huge district of working-class housing. The newness of the Tenderloin in the 1920s was a result of the rebuilding required after San Francisco's 1906 fire. Even without such a stimulus, however, landowners in other cities had found the same rebuilding necessary and profitable. In 1930, the Tenderloin had 59 percent of San Francisco's rooming house units. All of the new rooming house districts, together, had a third of the city's residential hotel rooms.[60]

For roomers in any type of rooming house district, a short journey to play was as important as a short journey to work. Rooming house areas relied on thoroughfares with heavy streetcar or bus service and commercial businesses that catered to people from throughout the city. In San Francisco, prime examples were Fillmore and Market streets. Like the thoroughfares that cut through the bright light districts of other cities, Market and Fillmore were busy at night with people going out to eat and be entertained at the theaters, vaudeville houses, movie halls, and large dance halls—the latter being prominent and often on the second floor above retail stores.[61] Inexpensive restaurants, cafeterias, bars or lounges, and variety stores filled the interstices (fig. 4.18).

Above the larger men's clothing stores were often pool halls. As one commentator put it, in such an area the clothing store signs always advertised for "gents," never for "men" or "gentlemen."[62] These bright light entertainments and retail bargains depended more on people from outside the rooming house zone than from inside it. Local residents relied more on smaller stores scattered throughout the zone: small bakeries, tailor shops, laundries, drugstores, shoe repair shops, and also (depending on the decade and local state law) corner liquor stores that also sold convenience food and snacks at exorbitant prices.[63] Nearest the workers' cottage or tenement districts were usually a few goodsized public bathhouses so essential for tenants who had hot water only once a week.[64] At the sleaziest or least expensive side of the rooming house area, but never far from the main thoroughfare, one would see astrologers' parlors, saloons, and fairly obvious houses of prostitution. No matter where one traveled in the rooming house zone, however, there were restaurants of all descriptions. Their role was central to the residents of the area.

Simple Food

On a day-to-day basis, the most important provision of the rooming house district was inexpensive food (fig. 4.19). Individualized dining was a major advantage of rooming houses over oldstyle boardinghouses. Boarders complained about eating at preset times, paying for meals whether they were there or not, not getting enough food, not having food they liked, and enduring very repetitious fare. While living in a rooming house, tenants could choose from a variety of places to eat, at varied prices, and over a much wider range of hours—provided payday was not too far away.[65]

The cheapest eateries were almost literally holes in the wall: tiny storefronts or basements, minimally adapted for their new uses. In Boston's South End in 1900, building owners converted house basements into small dining rooms managed, as Wolfe put it, by women "of uncertain experience." The atmosphere was dark, hot, and unfriendly. The beverage included with the meals could be either coffee or tea (one could not always be sure which it was, Wolfe said). However, the table d'hôte meals of four dishes cost as little as 20 cents each. Model boardinghouses run by home economists and settlement volunteers could not set a table at such low prices. At small storefront places in the industrial areas, the lunch fare was likely a cheap stew (potatoes,

Figure 4.19

Wallet card advertising a

beanery-style fast-food

emporium in New York City, 1901.

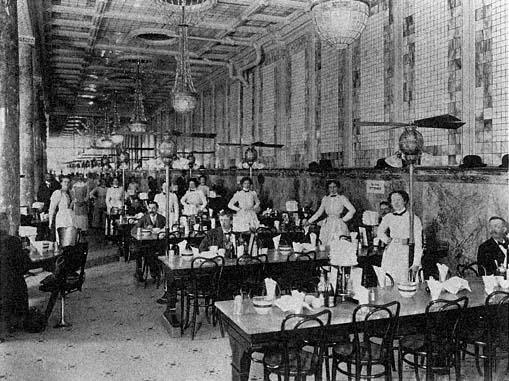

Figure 4.20

Child's Restaurant, a dairy lunchroom in New York City, ca. 1900.

carrots, and as little meat as possible) served with bread, pie, and coffee. Later, cafeterias and small counter-and-booth luncheonettes in rooming house areas continued the traditions of the small eateries. Through the 1960s, they remained a frequent haunt of rooming house residents.[66]

Larger basement restaurants offered similar bargains but better atmosphere. In the 1880s and 1890s, large and profitable places known as "three for two" restaurants catered to rooming house patrons, offering three 10-cent courses for two bits (25 cents). These eateries were a variation on the "beef and" restaurants, serving beans with a hefty cut of beef or pork, that sprang up after the Civil War.[67] Richardson, in the New York she knew during the late 1890s, occasionally treated herself with a good meal and a cup of hot coffee at a dairy lunchroom or quick lunchroom (fig. 4.20). Dairy lunchrooms were in large storefront spaces, attractively remodeled with white tile walls. They opened early and closed late. In some, tidy waitresses gave rapid service; in others, patrons picked up their food and ate at side-arm chairs. From a fairly large bill of fare, patrons could have a full dinner for 15 cents, order items à la carte for 5 to 7 cents, and efficiently pay the cashier in her cagelike desk.[68]

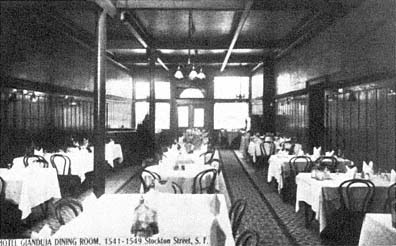

Meals in smaller new cafés were an even bigger treat for roomers who wanted a special dinner out. The range of Bohemian cafés in rooming house districts were typically known throughout the city for their informal dress, casual manners, and reasonable prices. Most cafés commanded a street view through plate glass windows and also had electric lights and fans. They were clean and attractive and had linen tablecloths. A steady café diet could cost $4.50 or $6 a week, as even spare breakfasts cost 20 cents; lunches, 25 cents; and dinners, 35 cents. Inexpensive hotel dining rooms essentially offered the same service (fig. 4.21).[69]

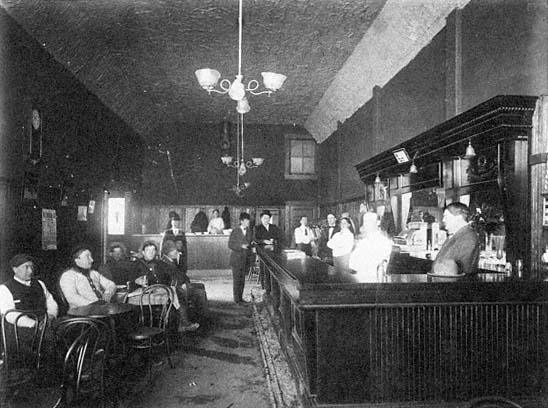

For convivial alternatives to the cafés, rooming house residents could turn to bars and saloons. Eating in a saloon was clearly working-class behavior and hence suspect for young people who aspired to the middle and upper class. Yet in 1912 a Philadelphia housing reformer defended the saloon with a positive description:

[Patrons at a saloon] could have a good dish of soup by purchasing a glass of beer for five cents. Often there is an egg, a clam, a fried oyster, or reed-bird

Figure 4.21

A small hotel's dining room. For rooming house residents, the Hotel Gianduja

in San Francisco's North Beach was a typical place for a special dinner.

given free with every drink. . . . For a very small price a hungry man can get as much as he cares to eat or drink. . . . As a rule the food is good, well-cooked, and palatable.[70]

Furthermore, he said, "That air of poverty which unfailingly pervades the cheap restaurants, and finds its expression in cheap and dirty table linen, is wanting in the saloon."[71] Polished oak or mission tables greeted saloon patrons (fig. 4.22). Richardson, too, was surprised one day when her fellow laundry workers whisked her through the women's entrance to a saloon. "Whatever the soup was made of, it seemed to me the best soup I had ever eaten in New York," she wrote, adding that she would "never again blame a working man or woman for dining in a saloon in preference to the more godly and respectable dairy-lunch room."[72] In the early 1900s, many saloons required that hungry patrons buy two beers to get the free lunch.

Other competitors to cheap cafés were illegal hot plates in one's room. Landladies often supplied these, to the concern of fire marshals. Regular diets of snack foods were available at the many neighborhood bakeries, delicatessens, grocery stores, and fruit stands. Their ready-to-eat bread, cake, cheese, and pickles supplemented the hot-plate fare.[73] Not only rooming house residents but also permanent guests at nearby midpriced hotels availed themselves of the delicatessen supplies.

In both the older, revamped neighborhoods like the Fillmore and the newer areas like the Tenderloin, the local dance halls and bars (or after

Figure 4.22

A plain saloon. After work hours, construction workers mix with young clerks in this San Francisco

saloon. Note the lunch counter at the rear.

Prohibition, the local lunch counters) often had a group of regular neighborhood customers. To the horror of her colleagues, the sociologist Margaret Chandler found a high degree of social cohesiveness in these groups. Social circles focused on one person's room or more frequently around a particular lunch counter, bar, or street corner. Some lunch stand groups behaved much as they might have in small towns. People stopped several times a day or night; on occasion, owners cooked up special meals for their regulars and extended them credit.[74] This social cohesion stood in sharp contrast to the alienation, anonymity, and illegal behavior that also characterized the mixtures of rooming house districts.

Beyond the Edge of Propriety

For people who wished to be anonymous and unnoticed, life in cheap hotels could be ideal. In a rooming house district, a small town Simple Simon might be teased less than he had been at home. People who wanted to live a liberated or illegal life

could do so in rooming houses and lodging houses more easily than in most other settings. For alcoholics or drug addicts, the fear of being discovered, the desire to be near some people like themselves, and the need to be close to supply sources brought them to hotels. Addicts could have seclusion if they wanted it, and desk clerks fended off investigators and pesky caseworkers.[75] Landladies might not remember or even know a new tenant's name. The frequent change of address possible at hotels, perhaps with a corresponding change in name, helped runaways elude their parents, reformed people escape their past, and criminals evade the police.[76] For anyone who wanted to melt into the physical maze of the city, such anonymity and the large number of rooming houses offered the perfect settings.

Given the large number of people seeking entertainment and anonymity in rooming house districts, red-light or vice zones logically overlapped with rooming house areas. In 1910, three-fourths of the parlor houses in American cities were in the rooming house and tenement fringes of the central business district. The architectural arrangements for small rooming houses in the 1910s could be almost identical to those built for parlor houses: rental store space on the first floor—inevitably a saloon in houses of prostitution—with parlors and the madam's suite on the second floor and many bedrooms on the third floor. For the prostitute residents, the madam's parlor house functioned as a boardinghouse or rooming house. A madam often listed her business in the city directory under the category of lodgings; notorious black sex clubs were sometimes advertised as buffet flats.[77] This overlapping of hotel life and prostitution was heightened in New York by a state vice law of 1896, which inadvertently produced "Raines Law hotels." Under the new statute, saloons could no longer offer free lunches, and hotels alone could sell liquor on Sunday and then only with meals. "In consequence," complained one legitimate New York hotel keeper, "every gin-mill in New York is now a hotel. It is easy to create a hotel. All you need is 10 microscopic bedrooms and some permanent sandwiches." At the turn of the century, Manhattan and the Bronx had 1,407 certified hotels, and 1,160 of them had apparently sprung up in response to the Raines Law.[78]

By the 1920s, decreases in general prostitution ironically led to an increase in prostitution in hotels. Business for women prostitutes had declined with the rise of the flapper—or more correctly, with shifts in

social mores for women that allowed women to be more sexually active and independent. Prohibition and Progressive Era attempts to protect young men—particularly the soldiers of World War I—from the Victorian versions of prostitution had decimated the flagrant red-light districts of many cities. Growing use of the automobile for sexual encounters moved prostitution to new locations. For the prostitution that remained downtown, hotels played a larger role as prostitutes' homes and as places of assignation. In San Francisco, a major vice crackdown of 1917 saw police raiding "hotels, lodging houses, and flats on streets which had never before known a house of prostitution." In national surveys in the 1920s, streetwalkers were found to be operating out of hotels twice as often as old-style bordellos.[79] Any of these social problems at times led rooming house residents to look for other housing options.