Buildings Purposely Constructed as Rooming Houses

Living in a "used" building—one constructed for something other than multiple residences—was for tenants a bit like wearing hand-me-down clothing. The cultural fit was often less than perfect, the social appearance sometimes embarrassing and demeaning.[18] In the struggle to establish respectability, a room that was new and solely intended to be a rooming house room could be an asset for better self-respect and public status. For managers, a purpose-built structure was easier to manage than an ad hoc one. All rooms could be an equal size, with no oversized or difficult-to-rent rooms. When American landowners chose to provide permanent hotel accommodations for this price range, they did so in two different ways: small purpose-built rooming houses and huge downtown hotels.

A great many new rooming houses were built downtown after 1900 on house-sized lots but usually with an improved, specialized type of building: the downtown rooming house .[19] These buildings improved on the livability of the former-house and generic-loft buildings. The construction was not temporary; owners were confident that single-room living would bring in reliable rents for a long time. On the ground floor were store windows and commercial spaces that in their form, use, and lease income clearly said "downtown." The fifteen to forty rooms on the floors above said "residential" to those living in the structure. Relatively generous light wells illuminated and ventilated the upstairs rooms and reinforced the permanent commitment to residential use. San Francisco's Delta Hotel, built about 1910 and still in residential use in the 1990s, exemplifies the type (fig. 4.5).[20] On the street level next to the storefront is a small door, demurely marked, with a narrow interior stairway extending to the eighteen rooms on the second and third floors (fig. 4.6). Public space is at a minimum; the only lobby is a wide area in the second-floor hall near the room that serves as an office and part of the manager's unit (fig. 4.7).

Renters sometimes called their purpose-built rooming houses "upstairs hotels." The phrase is apt, since before 1910, elevators were rare

Figure 4.5

Street view of a typical small

downtown rooming house, 1992.

The former Delta Hotel in San

Francisco's South of Market district.

Figure 4.6

Entrance door to the former Delta Hotel,

San Francisco.

Figure 4.7

Plan of the second floor in

San Francisco's Delta Hotel.

A room sink is next to the

case closet in each room; the

toilet room and bathroom

are off the rear hall.

Figure 4.8

Typical rooming houses in San Francisco. Top row , from left to right:

Isabel Cory's lodgings (shaded house), built ca. 1870; the Central Pacific

Hotel, ca. 1880; the Oliver Hotel, 1906. Bottom row: National Hotel,

ca. 1906; the Salvation Army's Evangeline Residence, 1923.

in hotels of this price range. Climbing one to four flights of narrow stairs was a modal and often reluctantly faced experience for residents.[21] Stairs figured in the letters written home by Will Kortum, an eighteen-year-old lumberyard clerk from a small California town. Kortum, who moved into a new hotel of the rooming house rank on his arrival in San Francisco in early 1906, wrote this to his mother after several weeks in the city:

I received your letter last night. It is always a feeling of great pleasure when the hotel clerk in answer to your inquiry for mail, dodges behind his desk and produces an envelope. And the long stairs seem a good deal easier to climb.[22]

Later designs for large rooming houses included elevators and floor plan arrangements that were variations on the plan for the Delta. By 1930, three-fourths of San Francisco's rooming house rooms were in taller, blockier buildings of five or six stories (fig. 4.8). Lobbies and dining rooms were small (if they existed), rooms were very simple, and there were rarely more than two chairs per room. Elevator or not, at this price range, most baths remained down the hall, at a ratio of about one bath to every five or six rooms. This far exceeded the one-to-fifteen

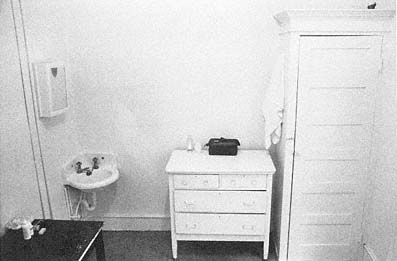

Figure 4.9

Room sink, dilapidated chest of drawers, and case closet in a large

rooming house, the National Hotel, San Francisco. In rooming houses

for men, sinks were often mounted lower than usual

and informally doubled as urinals.

ratio available in converted houses.[23] Another upward step in plumbing was a small sink in every room, typically on the same wall as a case closet—a closet built like a large cabinet or wardrobe rather than being built into the walls (fig. 4.9). The sinks, along with smuggled-in hot plates, made light housekeeping easy for tenants. For a larger rooming house, San Francisco's National Hotel is typical of the cheapest sort: no lobby, no frills, but ninety very regular rooms opening off very small light wells (fig. 4.10).

Whether found in small or large rooming houses, new or old, the conditions of one's room depended on the hotel's market and management. Matrons from the middle and upper class of San Francisco conducted a rooming house survey in 1926 and were shocked at what they saw:

There were dark rooms where it was impossible to find the washstand without first turning on electric light; dingy rooms where the carpets had a musty smell, and the furniture was shabby and faded; sleeping rooms with lumpy double beds and dirty lace curtains. . . . Most of the rooms had such dim lights that no one could read in the evening.[24]

The matrons could recommend only one-fourth of the downtown rooms they inspected. Sinclair Lewis had given a similar description in 1905, adding that the gas light "neither illuminated the mirror nor enabled the guest to read in bed."[25]

Figure 4.10

Floor plan of a large rooming house. The second floor of the National Hotel in San Francisco, built

ca. 1906. The location of the street entry is marked by a black triangle; the first room at the head

of the stairs is the office; toilets and baths are off the left rear hall. Shaded areas are light wells.

In a rooming house, one's room was never really isolated. Even for the very shy, life was indirectly social. After the third or fourth day, astute desk clerks would greet tenants by name. After two or three weeks, residents realized that they had begun to smell a bit like their hotel. At night, when the street noise died down, residents involuntarily monitored the activities and conversations in all the adjoining rooms. Coughing was a communal act; one always knew when one's neighbors had a cold. Carrying the sounds were light wells, floors, and walls built with minimal sound-deadening details; in hot weather or when the heating system overdid, hall doors and open transoms also carried sound. Personal affairs such as fights between couples could not necessarily be conducted privately behind closed doors.[26] For a guarantee of behavior better matching middle and upper class norms, some residents looked to rooming houses with more overt management.