The Social Art of Landscape Design

Marc Treib

In the title of his first major publication, Garrett Eckbo encapsulated his definition of, and attitude toward, landscape design. Landscape for Living rejected the garden and the park as provider of mere visual pleasure, as the setting for horticultural display alone, as the locus of the stylistic battle between the formal and the informal. Instead, a landscape was the site of the interaction of people and place, and landscape architecture—exterior spatial design—the purposeful formation of that interaction.[1] By the time of the book's publication in 1950, Eckbo had secured a professional reputation of international scope. With a handful of colleagues, he had tested and pushed the limits of how landscape architecture was practiced and, perhaps more important, how it was conceived. By midcentury, landscape architecture could rightfully claim a modern, if not always a modernist, orientation.[2] Admittedly, this was almost five decades after modernism had transformed painting and sculpture, and three decades after its acceptance as a viable approach to architecture. The path had not been easy, and it had taken some unusual turns along the way. Garrett Eckbo's own path began in New York.

Early Years

Eckbo was born in Cooperstown, New York, on 28 November 1910. His father possessed only limited business acumen and each of his proj-

Garrett Eckbo. Los Angeles, 1959.

[Julius Shulman ]

ects intended to advance the financial security of the family seemed to achieve just the opposite effect.[3] The result was a move west, first to Reno for his parents' divorce, and then to Alameda, California, with a new stepfather. Here the young Eckbo remained through his college years.

Growing up with "limited social opportunities," Eckbo says that he acquired both ambition and direction only after a half-year's stay in distant Norway with his paternal uncle, Eivind Eckbo, in 1929.[4] As he watched the economic and social success achieved through dedicated effort, Eckbo began to consider his options for the future, a future clouded shortly thereafter by the collapse of the international economy. He worked for two years as a bank messenger and at other jobs, attended Marin Junior College for a year, and entered the University of California in 1932. But what discipline should he study?

So I went through the catalog and I found a subject, landscape design, I think it was called then, in the College of Agriculture. And I thought, well, I always used to like to play with plants in the garden, and my mother told me I was artistic, so maybe I should try this .[5]

When Garrett Eckbo entered the University of California, the landscape program was already four decades old. Frederick Law Olmsted had designed the original plan for the then College of California in 1865, when the nascent institution moved to Berkeley from Oakland to escape the corrupting influence of the city.[6] The College of Agriculture added a course in Landscape Gardening and Floriculture in 1913, with John W. Gregg as professor. Katherine Jones complemented Gregg's strengths and interests with an expertise in plant materials. The curriculum intended to provide "both theoretical and practical" instruction, leading toward professional competence. In manner, the program was neither innovative nor retrograde, neither blindly formal nor uncritically informal, educating its graduates at levels commensurate with the national standard. The collapse of the stock market in 1929 and the ensuing depression colored the role of the landscape architecture profession throughout the country, as estate design gave way to public parks, land reclamation, and water management.

More directly influential in the formation of Garrett Eckbo's thinking was H. Leland ("Punk") Vaughan, whose ideas about landscape archi-

tecture contrasted with those of the more senior members of the faculty. A fortuitous meeting with University of California alumnus Thomas Church at Ohio State, resulted in Vaughan's appointment to teach courses in construction, and implicitly, in design. Francis Violich, who graduated from Berkeley in 1934, wrote of Vaughan:

Vaughan (age 25) brought a younger generation's forward looking point of view that provided common ground with the students of those changing times. His broader European and East Coast experience, his understanding of land building relationship, his exposure to modern design ideas, all seemed to turn the department around .[7]

Vaughan's presence thus stimulated in Berkeley students an openminded vision that questioned the complacency of landscape practice in the Far West. He "emphasized economy and clear thinking in the design studio, not as a source of style but as examples of design reflecting time, place, and people."[8] The writings and work of Garrett Eckbo reflect many aspects of Vaughan's philosophy.

Thomas Church, who preceded Eckbo at Berkeley by about a decade, had seen in the Mediterranean countries a source of inspiration and pragmatic parallels to the California condition. Even before the turn of the century the myth of California's Spanish past had played an increasingly influential role in forming the state's architecture. Helen Hunt Jackson's Ramona , published in 1884, described the carefree outdoor life of Mexican-America, the vibrancy of the patio, and the fragrance of the night-blooming vines.[9] By the 1920s a Spanish Colonial Revival was well under way in California, given authority by a 1925 municipal ordinance in Santa Barbara that prescribed buildings in the central district to be designed in idioms recalling Andalusia and other Iberian locales.

In the hands of talented designers such as James Osborne Craig, Lutah Maria Riggs, and George Washington Smith, the Santa Barbara works turned out magnificently, using plays of solids and courtyards efficiently and to great effect.[10] While romantic shopping complexes such as Craig's 1923 El Paseo used meandering paths and architectural mood to evoke mythical memories of Spain, the city's and period's true monument was the Santa Barbara County Courthouse of 1928 by William Moser. In both instances, landscape elements strikingly complemented the architecture, with the red, magenta, or tawny

hues of massive bougainvillea plantings staining the white brilliance of stuccoed walls.

Church's 1927 graduate thesis at Harvard was titled "A Study of Mediterranean Gardens and Their Adaptability to California Conditions," an announcement of Church's professional intentions after the requisite travel in Europe. Fortune brought Church and architect William Wurster together in the early 1930s, and together they developed buildings and landscape for the golf community of Pasatiempo near Santa Cruz. Despite his interest in the Mediterranean countryside, Church's work at Pasatiempo reflected the greatest respect for the native landscape, and his interventions with clipped plantings, lawns and beds, were quite restricted in both scale and exuberance.[11] Later in the decade, as his San Francisco practice began to flourish, Church's designs turned more elaborate, though still tending to rely on the established polite vocabulary of the Italian formal garden. Hedges and parterres of clipped boxwood, axial walkways, and nearly symmetrical dispositions paralleled the decorum of the architectural scheme. While the selection of native and subtropical plant species and a certain relaxed correctness characterized these garden designs, they were still heavily tinted by the manners of the Mediterranean past.

Eckbo recalls that although the University of California's landscape program tended toward a Beaux-Arts doctrine that applied formal ideas to institutional projects and informal ones to residential designs, Berkeley was just a bit too far from its continental sources to maintain true orthodox rigor.

It was a practical, pragmatic philosophy. It was not as doctrinaire as I found later in the East. It was just oriented toward solving problems and preparing students to work in the world the way it was then. It was a limited world in terms of design sources or design inspiration and ideas, which came basically from the movement of the old Beaux-Arts system into the West, where because of the climatic changes and other kinds of local problems, it was forced to become more practical and to adapt.[12]

The power of the California landscape normally diminished the formality of any scheme, softening any overbearingly geometric planting arrangements with an acknowledgment of view and cognizance of

sun and wind—a lesson that would never be neglected in Eckbo's designs.

Eckbo had little contact with contemporary currents in landscape design when he entered college, and no evidence suggests a greater awareness of them when he graduated. He took courses in drawing, plant materials, history and construction as well as studio, and emerged a skilled designer with festering ideas that extended beyond those of quotidian practice. With a wry, tongue-in-cheek title, Eckbo undermined the name of one assignment, if not the actual design [figure 1].[13] A gently undulating entrance road traversed the golf course, transformed into a formal approach to the parking court before the U-shaped country club. Each of the programmatic elements was addressed in a straightforward manner, but no big ideas transcended the assembly of parts.

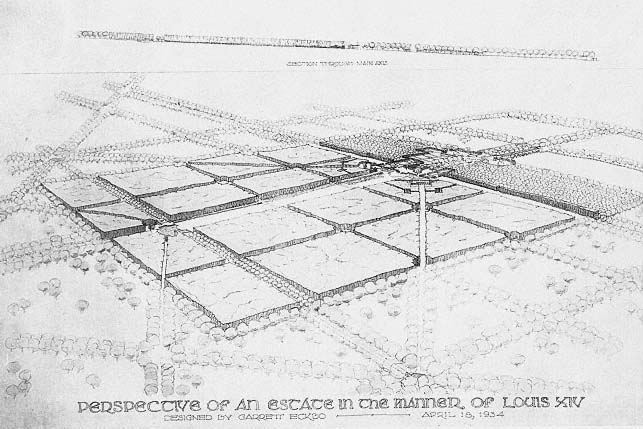

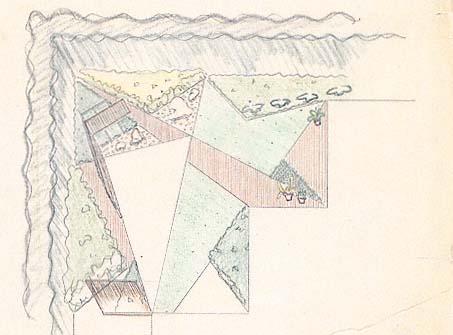

Seen from today's perspective, a third-year student project, An Estate in the Manner of Louis XIV, might be taken as completely ironic—but it was executed in all seriousness [figure 2]. The design was carefully planned and resolved, and a building or colonnade actively terminated the three allées of the trivium . A court formed between them set off the main "château" in a manner reminiscent of the central zone of André le Nôtre's design for Vaux-le-Vicomte from the 1660s. "This was perhaps the best plan I did [as an undergraduate]. . . . I was very interested in history when I was at Berkeley, and I practically memorized the Italian gardens—it wasn't so easy to memorize the French."[14] The first impression of yet another reduced replica of Versailles dissipates with greater scrutiny. While the prevailing central organization, cross axial scheme, and diagonal allées of the patte d'oie hark back to the formal gardens of seventeenth-century France, Eckbo tweaked almost every element of the classical plan, as a mannerist, if not a modernist. Given the openness of the curriculum, the tenor of the American economy, his commissions executed within a year after graduation, and his subsequent social vision, this design remains a complete—and charming—anomaly.

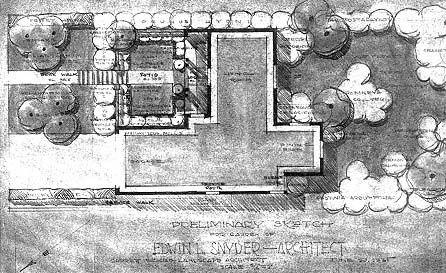

A plan for a small garden for Edwin Snyder [figure 3] demonstrated that the recent graduate could operate competently in more than the classical mode, although the scheme possessed no truly distinctive elements.[15] In many respects the design reinvestigated ideas for

1

Gottrox Country Club, Berkeley. Site plan. Student project at the

University of California, Berkeley, 1935. Watercolor on paper.

[Documents Collection ]

2

An Estate in the Manner of Louis XIV. Aerial perspective. Student project

at the University of California, Berkeley, 1934. Watercolor on paper.

[Documents Collection ]

3

Snyder garden. Rendered site plan. Berkeley(?), 1935. Pastel on diazo print.

[Documents Collection ]

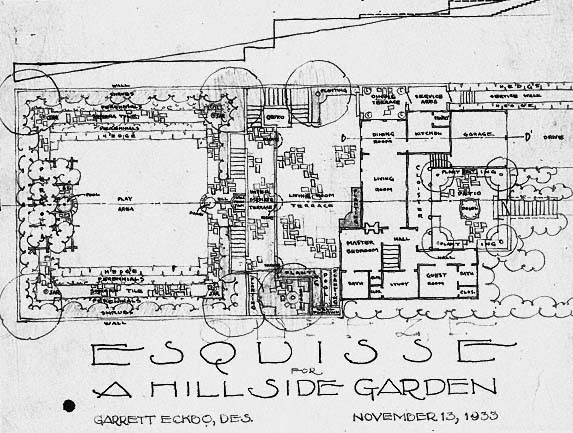

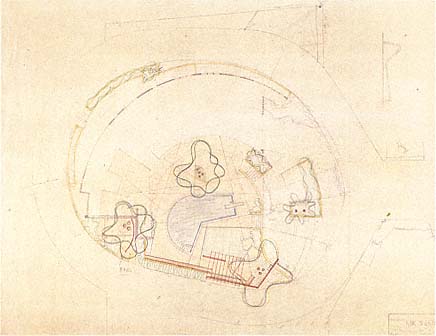

4

Esquisse for a Hillside Garden. Site plan. Student project at the University of California, Berkeley, 1933.

Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

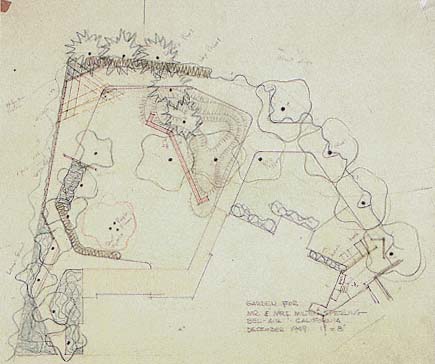

5

Forbes garden. Site plan. Glendale, 1936. Armstrong Nurseries. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

sequential zones characteristic of school projects such as the 1933 Esquisse for a Hillside Garden [figure 4], although its planting scheme was decidedly less rigid. A field of ground cover and two clumps of birches addressed the street, giving on to a rectangular enclosed patio that fronted the house's entry loggia. Masses of ceanothus and other shrubs disguised the borders of the lot to the rear and enveloped an exterior space that served as an extension of the living and dining rooms. Despite this early commission, the depression years were not a good time to enter private practice, and government work comprised almost all the available opportunities for landscape architects.[16] But John Gregg had helped arrange a job for Eckbo in Los Angeles and, a Bachelor of Science degree in hand, in summer 1935 the recent graduate headed south.

Los Angeles was hardly the sprawling, built-up, and smog-laden region it has come to be, and even today Eckbo retains only the fondest memories of his first years in the Southland paradise. He was employed by Armstrong Nurseries in Ontario to design gardens for its clients on sites ranging from the near-palatial to those of very modest dimensions. During his year working at the nursery, Eckbo designed about a hundred gardens, for which the average fee for

6

Flowers garden. Site plan. Temple City, 1935. Armstrong Nurseries. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

design was $10—refunded with the client's first purchase of $25 worth of plants.[17] The drawings for many of these projects remain. As a group they suggest that the landscape architect had already begun to question the notion of styles applied indiscriminately to contemporary California. Set in these terms neither the formal axes of France and Italy, nor massed tree clumps of the English landscape garden, were appropriate to a dry suburban backyard. The schemes also illustrate that relaxed plantings and spaces were beginning to take hold in California, for example, in the work of H. L. and Adele Vaughan. While Eckbo claims that he "hadn't even heard the word modern in connection with landscape design" until he reached Harvard a year or so later, the Armstrong Nurseries designs clearly reflect a simplified organization and a softened formality that would become a strong part of modern landscape architecture.[18]

While we might kindly term these designs contemporary, in no way could they be termed modern. In many of them the flavor of the estate is brought down to the scale of the suburban house. A lawn politely announced the entrance, with shrubs defining the street edge, and trees such as sycamores dignifying the principal facade. The schemes also varied in their degree of formality, at times more rigor-

7

Garden design. Site plan. Location unknown, circa 1936.

Armstrong Nurseries. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

ously Moorish, at other times, more fuzzy [figure 5]. For larger sites, a motor court brought the car to the garage and visitors to the front door. Each of the outdoor work spaces—the drying yard and cutting garden, for example—were screened by shrubs, and defined exterior spaces to the south complemented the primary rooms of the house. The orchard, however minuscule, was a common element in many of these works. Although organized rigidly, these tended to be specimen orchards that might contain papaya, citrus, persimmon, orange, avocado, tangelo, and apple trees all in the same grid [figure 6]. Presumably the effect would be less ordered in the reality of maturing trees than in the simple uniform diameter circles shown on the plans, revealing certain contradictions within the design or naïveté on the part of the designer.

The overall planting, in fact, was varied and rich—one might say, overcomplicated and at times, even garish. The linear extension of the house in one unidentified garden design, for example, terminated in a pair of acacias, each flanked by a deodar cedar and announced by a splash of white wisteria—a curious combination of species, to say the least [figure 7]. In some instances the planting schemes ran riot, bringing to a single site lines of myrtle and ranges of eucalyptus.

8

A Country Estate on an Island. Competition entry for a Harvard University scholarship, 1936.

Watercolor on paper.

[Documents Collection ]

Whether this variety stemmed from the young Eckbo's desire to try out as many plants as he could, to see what the more benign (if necessarily irrigated) climate of southern California could uphold, or just reflected the fact that he was working for a nursery—which, after all was in the business of selling plants—we can only speculate.[19] But in his mature years Eckbo never matched in exuberance the planting schemes of his year at the Armstrong Nurseries. His later palette relied instead on an armature of greens enriched by varietals and well placed patches of color.

Graduate Study

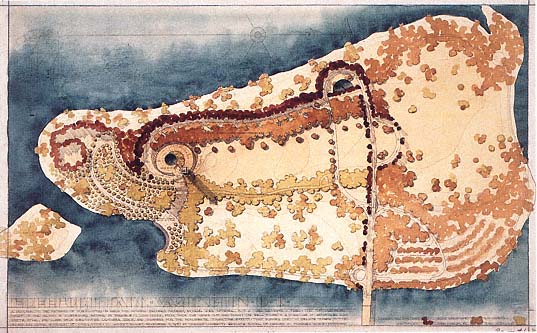

After less than a year of work, Eckbo could see that the horizons at the nursery were limited. The schemes were becoming "rote," and Eckbo was restless to expand his vision of landscape.[20] An opportunity for graduate study came his way by a scholarship competition sponsored by the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University. He entered the competition; he was successful. The winning design for a country estate on an island eschewed rigorous French or Italian formality, substituting instead a structured but less geometric development of the site [figure 8]. In the manner of Olmsted, or later

Fletcher Steele, the house was sited at the northern terminus of a broad lawn that linked the residence to the water. This greensward was leveled in the central area for "games" and gently bowed to exaggerate the sense of perspective from the shore up to the house. In the manner of the Italian Renaissance bosco selvatico , the wooded surroundings comforted a "casino" and outlook terrace; a more defined grassed swath opened eastward from the dining room, presumably for leisurely morning meals taken outdoors.

Eckbo acknowledges today that the design was "a fairly prosaic plan. There are probably twelve thousand gardens like this throughout the eastern part of the country. It has that kind of symmetrical informality that was begun at Mt. Vernon, which was the colonial period's contribution to ongoing design ideas."[21] But as a whole, the design was thoughtful and resolved. While the small sketches successfully illustrated the various architectural events on the island, neither the scheme nor its ink and watercolor rendering could match the brilliance of Eckbo's Beaux-Arts counterparts in France. But the entry was awarded first prize and secured for Eckbo a scholarship for further studies in landscape architecture. With his friend Francis Violich, Eckbo headed east, optimistic about the prospects of Ivy League education despite the lingering effects of the depression.

After a year at Harvard, and summer work in the Boston area, Eckbo traveled to New York to visit—and marry—Arline Williams [figure 9], the sister of his Berkeley classmate and future partner, Edward Williams.[22] During his first year of study, the graduate student found the curriculum superficially similar to that at Berkeley, and yet more rigidly entrenched. Henry Vincent Hubbard reigned as the theoretical head of the department, and the Beaux-Arts method formed the crux of his approach to design. The 1936 Harvard University Register defined landscape architecture as "primarily a fine art, which aims to create and preserve beauty in the efficient adaptation of land to human use."[23] Hubbard and Theodora Kimball's Introduction to the Study of Landscape Design codified this vision of landscape architecture and was regarded with near-reverence:

A work of art which has style may be esthetically organized in either of one of two fundamentally different ways. The artist may design his work to express his own ideas, to serve his own uses, to show his control over some of the materials and forces of

9

Arline Williams. Cambridge,

Massachusetts, 1938.

[Courtesy Arline Eckbo ]

nature. Or on the other hand he may design his work to express to the beholders the understanding which he has of some modes of nature's organization, and the pleasure he finds in them. In the first case, the esthetic success of the work will require that the hand and the will of man be visible in it; in the second case, the higher art would be that which so perfectly interpreted nature's character that the work should seem to be a wonderfully complete and intelligible expression of nature's self .[24]

As Eckbo remembers his Harvard education, its central issue was the designer's visibility, usually expressed as the difference between the informal and formal garden traditions. Most problems, he claims, were stated in terms of that very broad dichotomy. And in his writings, Eckbo hammered away at the false distinction between the formal and informal modes while—ironically—dividing the world's garden traditions into exactly those two categories. To him the particular style in which a landscape was executed mattered less than the intention behind that vocabulary—which should not be a question of style alone. In 1941, some three years after he received his master's degree, he wrote:

The formal garden forces architecture upon the landscape; the informal garden forces the landscape upon architecture. Neither does anything toward the basic problem of garden design: the integration and harmonization of the structural geometry of man with the biological growth and freedom of nature. This can't be done by holding them apart and calling one formal and the other informal. The fundamental fallacy seems to be that a choice between the two extremes is necessary. The argument has been to take either biology or geometry; why not biology plus geometry?[25]

Eckbo's telling of the story was based on a useful form of simplification. In fact, as Reuben Rainey demonstrates, the Beaux-Arts approach was more subtle than the modernists made it. Rarely was any project entirely formal or entirely informal; almost always the rigidity of any scheme would need be softened by the particularities of the site and program.[26] While perhaps propelled to a greater degree by a geometric structure, the formality of the garden scheme was tempered and enriched by climate, plant materials, and the client.

Like any theoretical stance, this method was never as fixed as its opponents believed it to be; the presentation of the Beaux-Arts beliefs by Hubbard and Kimball was intelligent, comprehensive, and accepting of infinite manipulation and variation. To the graduate student, it didn't seem that way at the time. Eckbo's own copy of Hubbard and Kimball is filled with argumentative marginal notes that spoke back to the authority represented by the text.[27] While transparently the churlish cartooning of a prior era by the hand of its successor, these jottings reveal just how seriously Eckbo took his education, and how seriously he set the course for a modern landscape architecture.

However one may qualify Eckbo's caricatured retelling of his days at Harvard, there is no question that landscape pedagogy lagged well behind that of the architecture program. Joseph Hudnut had become the dean of the newly formed Graduate School of Design in 1935, bringing with him ideas about modernism and a renovated curriculum. "Our exigent problem is that of our place in the world," Hudnut wrote. "If indeed architecture can exist amidst airplanes, dynamos and motion pictures, it must seek a reconciliation with them, discovering a new grace and order in the very heart of contemporary technical processes."[28] Under Hudnut's invitation, the former Bauhaus director Walter Gropius came to Harvard in 1937 and, with Marcel Breuer, injected forefront European ideas about architecture and its social role into an American context. This connection, more than any issue of style, is what Eckbo would carry away from his courses in the architecture department: the link between society and what he would later term "spatial design." While landscape design embraces "surfacing, enclosure, enrichment," a designer strives to "give the richest, most plastic and satisfying form to the space which is being organized; the other is to concentrate always on that space as an arena, volume background, and shelter for human life and activity."[29]

For Gropius, "the term 'design' broadly embraces the whole orbit of man-made, visible surroundings, from simple everyday goods to the complex pattern of the whole town." Critics had questioned, with good reason, the Modernist project's efficacy in designing cities. Tellingly, there was no instruction in landscape architecture at the

Bauhaus. Eckbo's concern for art and science paralleled those advanced by Gropius and other architects who saw the need for creatively addressing new materials, standardization, and rationalized fabrication. "Good planning," wrote Gropius, "I conceive to be both a science and an art. As a science, it analyzes human relationships; as an art, it co-ordinates human activities into a cultural thesis."[30] This last sentence alone could have served as the basis for Eckbo's forthcoming master's thesis project.

In addition to the other European émigrés, Hudnut also invited the Canadian-English landscape architect Christopher Tunnard to teach at the Graduate School of Design. In 1934, recently graduated from the Royal Horticultural Society school at Wisley and the Westminster Technical Institute, he began to publish a series of articles in the journal of the Landscape Institute, and later the Architectural Review . Tunnard sought not only a modern manner for landscape design, but more profoundly, an approach that would avoid questions of style altogether. He, too, acknowledged that landscape history had fallen into considerations of formal and informal, but he found in Japan the "empathetic" manner by which a concern for the social and ecological landscape could transcend the very question of style: "This conception of Nature and natural forms finds one of its expressions in Japan (and it is beginning to in Europe) in the unity of the habitation with its environment."[31] Tunnard's essays ranged in subject matter from investigations into British landscape history to the use of sculpture in gardens, and were collected and published in 1938 as Gardens in the Modern Landscape . The tract would remain the sole English-language polemic for landscape modernism until the publication of Eckbo's own (and more comprehensive) Landscape for Living in 1950.

That Tunnard sought to draw landscape design into tandem with architecture and other modern arts underscored his belief that landscape architecture must be a social art as well as a social science. While the implicit argument for an expression in accord with the times is buried in the text, he rooted his argument in reason, history, and problem solving. Indeed, in an article published during the war years, Tunnard proposed that "the right style for the twentieth century is no style at all, but a new conception of planning the human

environment." As James Rose had suggested several years before, Tunnard proposed modern architecture as the role model for a contemporary approach to landscape design: "Modern landscape design is inseparable from the spirit, technique, and development of modern architecture."[32] Clearly, the emerging generation saw its future in parallel with architecture rather than with the more specific investigations of painting and sculpture. While the latter almost always stood far in advance of the "social arts"—and avant-garde—in most instances they lacked a client, a program, and space—all requisites of landscape design.

Although locked into a more ossified theoretical stance than its architecture counterpart, the landscape program at the Graduate School of Design allowed its students the latitude to take courses in other subject areas and strike out on their own in both formulating and designing landscapes of their choosing—or at least subvert their studio assignments. Certain of Eckbo's projects were controlled by a formality not totally foreign to the work he had produced at Berkeley or during his year at the Armstrong Nurseries. By this time, however, narrow columns of explanatory text began to accompany each assignment, as a sort of sermon on landscape theory. For one project for a country estate, the notes read:

A country estate: a place where people live in the country; in intimate and sympathetic relation with the landscape; areas used by man, formed by man in an intelligent and unashamed manner. Areas unused by man left natural. Developed and undeveloped areas concentrated so as to achieve maximum effect from each, and contrast of two together. A forecourt is a reception room for automobiles, let it be an extension of the house, not an approach to it. People like to dine out of doors, swim and play tennis in gay surroundings, sit and walk in the shade, and look out on a pleasant, spacious view .[33]

The estate's design continued the long tradition of more formally planned areas—forecourts, terraces, and orchards—set against the naturalistic order of the woods, in essence, continuing the play between geometrically and informally planned zones.

If these early assignments suggested a wavering between what he had learned at Berkeley and what he was acquiring through his

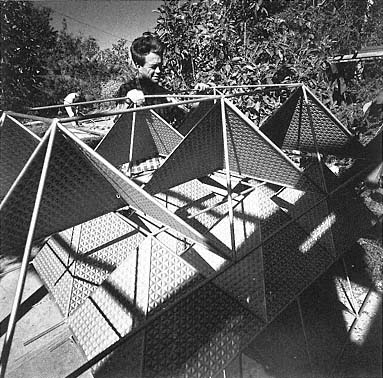

10

Freeform Park, Washington, D.C. Partial site/planting plan. Student project at Harvard University, 1937.

Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

architectural forays at Harvard, the design for a Freeform Park in Washington, D.C., left no question about his future direction.[34] The overall planning of the island site in the Potomac was asymmetrically developed, heavily weighted toward its western tip [see plate I]. The approach road cut northward across the island before veering west toward the park's central space. Here, tree plantings spiraled toward a round pool at the plaza's center flanked by a tower made of two concrete slabs (architecture student friends helped Eckbo on the design) [figures 10, 11]. London plane trees prevailed, lining the edge of the road and enclosing the plaza. A grid of ornamental apple trees (Malus sylvestris ) was planted as a foil for the roads and for clumps of locusts and maples.

11

Freeform Park, Washington, D.C.

Sketch of the tower. Student

project at Harvard University,

1937. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

The note accompanying the rendered site plan dispelled any doubt about the author's patriotic and artistic intentions behind the design:

A memorial to the fathers of our country in which the informal becomes modern, modern goes informal, but a tree remains a tree. The topographical spirit of the island is preserved insofar as possible: a low ridge, from which one looks out and down. The bell tower is a structure of reinforced concrete, steel, and glass, which substitutes lightness, grace, and openness for the monumental tombstone effect. Tree masses used to relate tower to the island and define movement of circulation .[35]

Even at this early date, we see Eckbo bristling against the simple bifurcation of approaches to landscape into the informal and the formal, and to the application—however updated—of received ideas. Instead, he was searching for a new vocabulary, a vocabulary like the International style in architecture, to announce the arrival of modernity. More important, this idiom would signal a new regard for landscape architecture in society. His search sought sources in architecture, painting, and sculpture.

The New Space of the Garden

Modern architecture suggested that space was the most important aspect of landscape or architectural design. As Eckbo later wrote in Landscape for Living , when we purchase a lot, we are actually buying a block of space—why be concerned with only the design of its surface [figure 12]? Spatial design is achieved through both inert and

vegetal materials, and seen in this light, the quests of architecture and landscape are actually congruent. That one discipline produced roofed space and the other spaces open to the sky, to Eckbo was no viable reason for this artificial division. In truth, both professions shared a common goal: a landscape for living, if landscape be taken in much broader terms to include people and their relationship to the land.[36]

Eckbo shared this interest in space with the architects of his generation and with his landscape classmates as well. James Rose would become one of modern landscape architecture's most polemical writers during the 1940s, beginning to publish almost as soon as he left school. In the 1938 article "Freedom in the Garden," for example, Rose, like Eckbo, noted the affinity between landscape design and sculpture. What distinguished the two, however, was the focus on space: "In reality, [landscape design] is outdoor sculpture, not to be looked at as an object, but designed to surround us in a pleasant sense of space relations."[37] Using illustrations of drawings by Picasso, houses by Mies van der Rohe, and sculpture by Naum Gabo—paired with images of his own projects—Rose sought parallels in the arts to propel developments in landscape architecture.

In The International Style , Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson advanced a concern for space over mass as a defining characteristic of modern architecture. Like Frank Lloyd Wright's citing of Taoism and in particular Lao Tzu in "the reality of the vessel is the space within," the formation of space and the use of space by human beings became central issues in Eckbo's work.[38] His appreciation of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's 1929 German Pavilion in Barcelona was obvious in his writings and in his designs, in particular the use of the overlapping rather than intersecting corner. And in projects ranging from suburban backyards to expansive housing estates, plant materials and constructed planes were first and foremost addressed to defining space. The forms by which space was delimited followed closely thereafter.

But what of the particular vocabulary that would form the modern landscape? To appear contemporary one might investigate the most free of aesthetic investigations: painting and sculpture. In an early article, "Sculpture & Landscape Design," published just as he was com-

12

"Your Block of Air." Carlos Diniz,

delineator. [ from Garrett Eckbo ,

The Art of Home Landscaping]

pleting graduate studies, Eckbo stressed the intrinsic connection between architecture, landscape, and the plastic arts. Although emphasizing the essential unity of the arts, he cautioned that "landscape design concerns itself with provision for the outdoors activities of man."

Architecture [like sculpture] . . . works with three-dimensional volumes, but their arrangement is governed by human activities which they must shelter. . . . Yet sculpture is also analogous to landscape design, for the handling of ground masses can be carried out with a truly sculptural sense of forms in relation. In fact, landscape design may be considered more analogous to sculpture, since its forms are moulded and carved and grouped, whereas those in architecture are constructed.[39]

Alfred Barr, founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, had analyzed the development of abstraction in painting and sculpture and distinguished between "pure-abstraction" and "near-abstraction": "Pure-abstractions are those in which the artist makes a composition of abstract elements such as geometrical or amorphous shapes. Near-abstractions are compositions in which the artist, starting with natural forms, transforms them into abstract or nearly abstract forms."[40] This dichotomy opened a conceptual application of the contemporary plastic arts to landscape design, suggesting to designers their role as the designers of habitable near-abstractions.

13

Pierre-Émile Legrain. Tachard garden.

La Celle-Saint-Cloud, France, circa 1924.

Sketch by Garrett Eckbo from a photo.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

Barr included architecture, film, furniture, graphic, and theater design in his exhibition "Cubism and Abstract Art," but landscape architecture was notably absent, as it had been from the Bauhaus.[41] Yet even in this century, garden designers—often architects or interior designers rather than landscape architects—had explored the links between the aesthetic zeitgeist and outdoor space. Most obvious was the "cubistic" idiom of Gabriel Guevrekian's Garden of Water and Light at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, and his walled garden for the Villa Noailles in Hyères executed three years later. The landscape profession was introduced to the French work through publications—all in French and virtually linguistically inaccessible to the young Americans, with the notable exception of Fletcher Steele's 1930 "New Pioneering in Garden Design." Eckbo was so impressed with a view of Pierre-Émile

14

Jones garden. Site plan. Ontario, late 1940s(?). Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

15

Garrett Eckbo and James Rose on a student excursion, 1937.

[Courtesy Arline Eckbo ]

Legrain's Tachard garden in La Celle-Saint-Cloud, he overlaid the photo to produce his own sketch for further study [figure 13].

It blew my mind because of that little sawtooth edge, which you probably think is kind of silly, but it made me think about what a path is for. A straight path with straight sides is a linear movement through space, designed to get you from here to there as quickly as possible. It's like a street or highway. But if you break the edge like that, you say that there's something along the side that maybe you should stay and look at. It was a form that came out of modern art .[42]

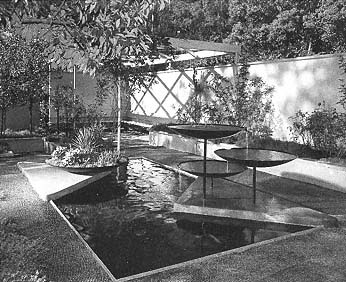

While the zigzag path rarely maximized its effect on movement in the Eckbo garden, it became one of the landscape architect's favored design motifs. And the influence of the banked earthen planes—in pattern, if not actual form—of Guevrekian's Garden of Water and Light and Legrain's Tachard garden are most obvious in Eckbo's studies for the segmented patterning of the Jones garden (Ontario, undated, probably late 1940s) [figure 14; see plate IV].

As a graduate student, Eckbo was well aware of developments in the arts, and the bibliographies of his articles and books balance readings in the arts with sociology, soil conservation, and planning. In "Sculpture & Garden Design," which appeared in the Magazine of Art in 1938, his setting for a modern sculpture reworked the spiral row of trees that enclosed the plaza of his Freeform Park project. But here the motif had been adapted for purely aesthetic ends. Intended to terminate the allée of a large garden, the design's "ramped earth

16

Garrett Eckbo and Dan Kiley at the beach. Cape Cod, 1938.

[Courtesy Arline Eckbo ]

planes meet at a low mound, from which rises a piece of modern sculpture whose smooth forms blend readily with the earth forms." Archipenko's Hero became the central feature of the design, an image appropriated from Alfred H. Barr's Cubism and Abstract Art first published in 1936.[43] This borrowing was no doubt intended to add a gloss of modernity to the design's vegetal elements. In any event, the article's publication offered Eckbo a national arena in which to broadcast his views—certainly among the earliest exposures of modern landscape to the American public.

Eckbo was not alone in his quest for a modern landscape architecture. His Harvard classmates included James Rose and Dan Kiley, and the trio would come to play a pivotal role in twentieth-century American landscape architecture [figures 15, 16].[44] Given their callow youth and radical ideas, it is startling that the band found a forum for their writings so early on, and that they chose to attack global problems and theories rather than small-scale garden design issues alone. In 1939–40, they jointly published a series of articles that laid out an approach to design based on a three-part division of the earth into primeval (i.e., wilderness), rural, and urban landscapes. Citing Lewis Mumford in the essay on design in the primeval landscape, they asserted that it is impossible to design responsibly in any of the three arenas without considering—and affecting—the remaining two. In closing, they stressed that "the design principles underlying the planning of the urban, rural and primeval environments are identical: use of the best available means to provide for specific needs of the specific inhabitants; this results in specific forms."[45]

17

James C. Rose, Bibby estate. Kingston, New York.

Student project at Harvard University, 1938.

[ from James C. Rose, "New Freedom in Garden Design" ]

18

Pablo Picasso. Figure , 1910.

from James C. Rose, "New Freedom in

Garden Design" ]

Perhaps not surprisingly, it was the architecture journals that gave space to Rose and Eckbo for their writings. In "Freedom in the Garden" Rose argued for a landscape design that was spatially based, which he illustrated with modern architecture, painting, and sculpture as well as his own projects. The images were used rhetorically. A plan of his 1938 Harvard school project for the Bibby estate in Kingston, New York, was paired with Figure , a drawing by Pablo Picasso [figures 17, 18]. Other examples were drawn from the work of Theo van Doesburg, Mies van der Rohe, and Naum Gabo. In projects undertaken as a graduate student, Rose clearly demonstrated his comprehension of modernist architecture, as he applied its notions of spatial fluidity to the garden. In 1940 he wrote that "we are already accustomed to a freer type of space organization—living/dining rooms with groups arranged for conversation, study, and play. . . . We have yet to develop the house and landscape unit on the same basis rather than just the house with the garden attached."[46]

Although a socially reinvigorated landscape architecture adapted its aesthetic vocabulary from contemporary plastic arts, underlying both was the spirit of the times—and a belief in progress and most of all the positive rational power of science. Science and the promise of technology in realizing the democratic ideal were frequent themes in both Rose's and Eckbo's writings. Gropius had written that the new architecture derived not from the personal aesthetic tics of a handful of designers but "simply the inevitable logical product of the intellectual, social and technical conditions of our age."[47]

Vaguely defined and open to a variety of interpretations, the positive impact of technology ran as a common thread in publications by various authors on landscape design. Tunnard wrote about science in 1938, restricting his purview to the development of hybrid species and the improvement of the soil:

Just as the design of the locomotive, the aeroplane, and, for that matter, the modern house, is being changed by scientific invention, in a similar way, science will transform the garden of the future. The latter must necessarily be influenced by new materials and their methods of application—for example, by plant importation and hybridization, and the amelioration of soil and weather conditions .[48]

Rose pushed the matter further but diverted the topic of discussion in his 1939 article "Why Not Try Science?" He bemoaned the fact that landscape thinking lagged so far behind developments in architecture, hampered by the employ of traditional building materials and plant varieties. Science was not an abstract idea, he claimed, but instead directed the landscape architect's working method. More specifically—and surprisingly—a scientific use of plants meant avoiding plants used in masses: "It is only by the isolation of specimens that plants can be controlled scientifically, developed to the ultimate of their potential characteristics, and used with elastic tensility. It is the method employed in all scientific investigation in horticulture—and in the study of building materials." In fact, if science has anything to demonstrate, wrote Rose, "it has proved that so-called 'natural' conditions are not necessarily the best conditions for development." Having dismissed the emulation of nature as impossible, Rose made absolutely no apologies for his view:

It is perfectly possible to use plants with the same knowledge and efficiency with which we use lumber, brick, steel, or concrete in building. And when we apply the science of growth to our landscape design standards, so that we can determine accurately the form characteristics and definitely establish the growth rates for individual plants under given conditions, we will be able to use plants with the same expediency as the factory-made, modular unit in building .[49]

The influence of modern architecture on Rose's thinking appears to have been decisive, no doubt inculcated by his training under Gropius. Curiously, Rose offered no more than broad notions of landscapes appropriate to contemporary living; he rarely spoke of the specific use or user group for these landscapes. His concern fell almost completely on spatial and formal ideas, with few specific notions of people, modern thinking—or science.

Science

By the time Landscape for Living was published, Eckbo's view of science had been greatly modified. In the immediate postwar era, with the world again free for democracy, almost everything seemed possible. Technology reappeared as a fully positive force and, with it, the

optimism witnessed at the 1939 World's Fair in New York. In the introduction to Landscape for Living , "Why Now," Eckbo announced his desire for "a serious analysis, in terms of theory and practice, of landscape development in our culture." The advance of the scientific method in all fields of inquiry, including less "exact" fields "such as esthetics and sociology" occasioned this study: "The scientific method is one which takes nothing for granted, accepts no precedents without examination, and recognizes a dynamic world in which nothing is permanent but change itself." Thus, to Eckbo, science was less a force or a body of knowledge than a stance by which to re-examine his discipline, landscape architecture. He quoted Christopher Cauldwell: "Art is the science of feeling, science the art of knowing. We must know to be able to do, but we must feel to know what to do." Put into Eckbo's own terms, this is the difference between "know-how" and "know-why:" "Theory is the why of doing things, practice is the how. If practice is know-how, theory is know-why. Theory must serve practice; must answer the questions raised by practice; and must be tested by the data of practice."[50] Seen in these terms, theory and practice are complementary, helping landscape architecture—which becomes a humanistic science—create appropriate outdoor settings for human existence. This theme recurs through almost all of Eckbo's writings, reflecting—if not as forcefully—the conviction with which he advanced it in Landscape for Living .

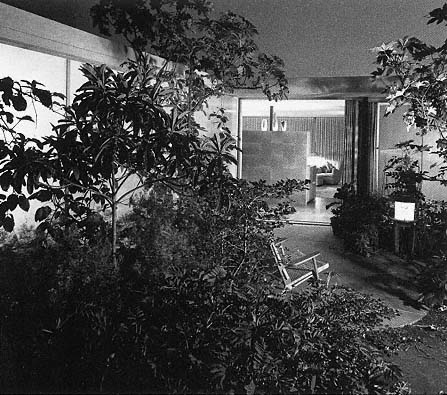

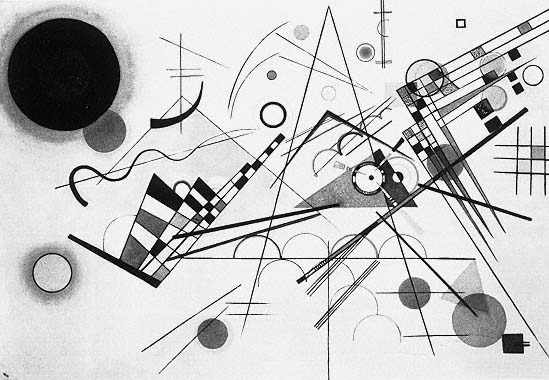

The call for a scientific method for landscape architecture raised questions as to its manifestation as garden form and space. On the one hand, designers hold conceptual interests that address broader, almost intangible, issues such as "contemporary living," "technology," and "science." These rarely find a direct, perceivable expression in any landscape design and serve primarily to propel the designer in his or her work. Thus, these factors tend to color the values behind the design but lack a direct expression within it. On the other hand, the perceptual concerns demand an expression appropriate to the designer's values and aesthetic sensibility. It was at this level that investigations in the other arts were so important for the development of the modern garden in California. Shapes, forms, and spaces drawn from the work of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Wassily Kandinsky [figure 19], Mies van der Rohe, László Moholy-Nagy [figure 20], Naum Gabo, El Lizzitsky, Joan Miró, Jean Arp, and Isamu Noguchi

19

Wassily Kandinsky. Composition 1 , 1921.

[Yale University Art Gallery ]

20

László Moholy-Nagy.

Composition no. 4 , 1923–24.

[Katherine S. Dreier Bequest, © 1996

Museum of Modern Art, New York ]

were as important for what they were not as for what they were: they were neither the informal nor the formal tradition. Instead their idiom spoke of today, of design in space.[51]

Painting, Sculpture, and Landscape Design

More significantly perhaps, modern painting signaled the arrival of non-perspectival space, an idea with which landscape designers could counter the thrust of the formal axis or the informal clump. Joan Miró spoke of the "motionless movement" he sought in painting, another idea with possible application to the new garden: "As there is no horizon line nor indication of depth, [the forms] are displaced in depth. They are also displaced in plane, because a colour or a line leads fatally to a displacement of the angle of vision. Inside the large forms, small forms move. And, when you look at the whole picture, the large forms become mobile in turn."[52]

Denied the picture plane, painting could become a space without areal boundaries and possessing infinite depth, undermining the reading of the painting as a representation with ties to the objective world. The space and movement of a landscape employing the elements of nonobjective painting—here turned into "nonobjective spaces"—could better accommodate contemporary living outdoors. The years at Harvard constituted a pivotal stage in Eckbo's formation; and academic study gave him a laboratory for pure research and its applied development. Several design studies investigated the linkage of modern art with Eckbo's more socially rooted ideas.

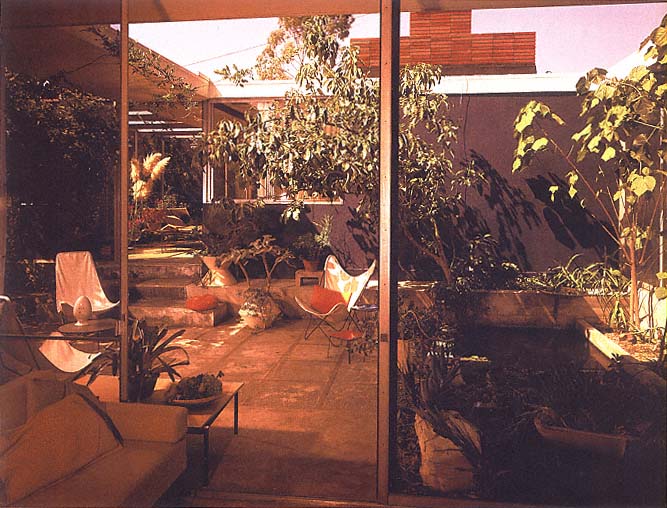

The 1937 project for, and subsequent publication of, "Small Gardens in the City" functioned as an advanced manifesto for the urban landscape [figure 21]. The undertaking was entirely self-motivated, intended to serve as a near-culmination to his graduate study—a thesis would follow—and a testing of ideas concerning the elements of a modern urban landscape.[53] Eckbo developed the design of eighteen gardens on a single city block, patterned in dimension on the urban units of San Francisco with which he was so familiar: "This was a study of design possibilities—a study of physical form, based on the idea that the content would develop over time."[54] The architecture of the houses to complement the gardens was more or less assumed and in the end mattered little in terms of the site design—other than the functional connection between indoor and outdoor spaces.

21

Small Gardens in the City. Model. Student project at Harvard University. 1937.

[Documents Collection ]

The site sloped slightly, affording minimal opportunities to sculpt the terrain. The gardens—presented in model form as an entirety and individually as axonometric ink drawings—developed variations on particular themes [figure 22a-d]. Some designs seem to have begun with the limits of the site and worked inward; others expanded outward from the living spaces of the house. The thrust of the designs varied from those aligned with the shape of the lot, to those turned obliquely to the walls, to those using a less geometric idiom as a means to distance the garden from the rectangular bonds of the lot. In one garden, arc segments descended the slope in overlapping terraces; another employed a geometry rotated 45 degrees to the edges of the site. The modeled ground plane acquired a third dimension, and considerable tracts of paving complemented areas of low vegetation and ground covers. Tree plantings were arranged more freely, in places appearing more as sculptural elements than as providers of shade and mass. Pergolas and other light structures completed the designer's palette.

With all their innovation and individual formal brilliance, the eighteen gardens created little sense of a continuous landscape; they remained discretely conceived and bounded. Only in certain minor gestures—like the zigzag fence that traversed the property limits—did Eckbo challenge the tyranny of the lot line.[55] The street side of each house was left untouched. Like a botanical garden, with each plot assigned to a different plant family, each unit tested a varied formal vocabulary but left the greater question of the urban landscape conglomerate unquestioned. Eckbo would address this issue in his thesis, Contempoville, completed the following year.

Conceived as an independent school project, "Small Gardens in the City" was published within six months of its completion in Pencil Points , one of the United States' leading architectural journals. Taking stock of his audience, Eckbo wrote an explanatory text, laying the ground rules for the small bounded site and elucidating the assumptions behind his investigations. He cited his original thoughts and added an updated commentary in a 1993 memoir:

"Gardens are places in which people live out of doors."

"Gardens must be the homes of delight, of gaiety, of fantasy, of illusion, of imagination, of adventure." These

a

Abstraction of natural contours, curved terraces

follow nature slope. Curves need be neither

"noturalistic" nor "formal." Any garden made by

man is formed, therefore formal. Outside

connection of garden with second-story living

room is very important to unity of house and

garden and circulation.

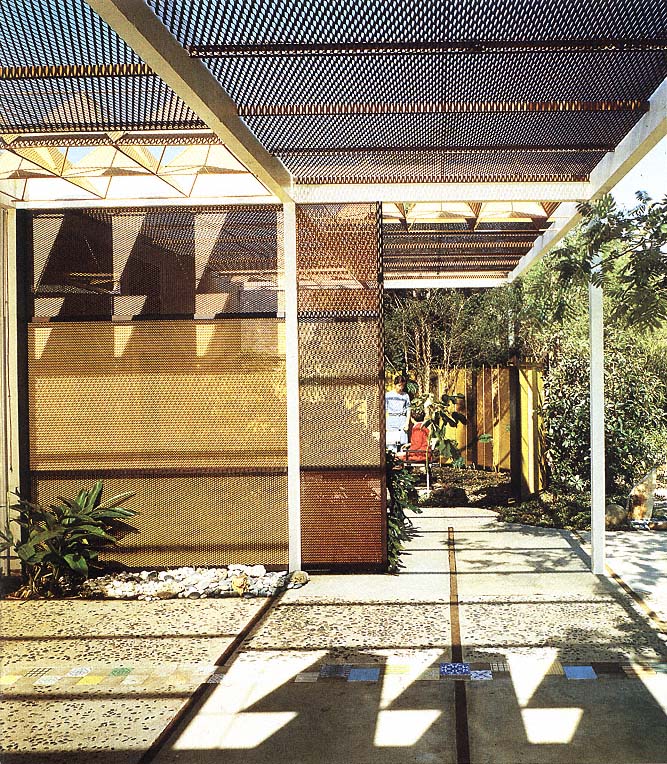

b

Spatial design. Shape of an area warped to break up

feeling of hard enclosure. Colonnade gives distance

by partial concealment and enframement of lower

end of garden. Ample planting space. Change in

property line by agreement between two owners.

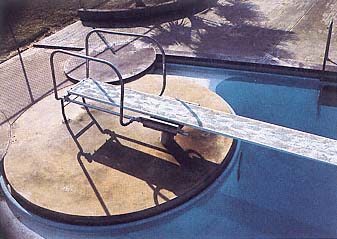

c

Repetition of a simple square turned at a 45-degree angle.

Line of descent follows natural slope. Plants as specimens.

Water either moving or soil. Abstraction of natural forms,

the spirit, nor the semblance.

d

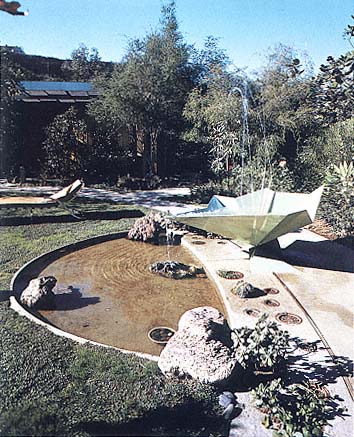

Water garden. Population of aquatics, fish, frogs,

and turtles. Thrill of crossing by stepping stones

to lower sitting area. Pattern from second-story

living room.

22a–d

Small Gardens in the City. Axonometric studies.

Student project at Harvard University, 1937.

Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

are not physical qualities. The assumption was that bold and free arrangements of space and material would generate such feelings and responses .

"Designs shall be three-dimensional. People live in volumes, not planes."

"Designs shall be areal, not axial." . . . Spatial experience is more than a line .

"Design shall be dynamic, not static." . . . Axial design tends to be static, its obvious purpose being to express and freeze the status quo. We do not want to live in a static world .[56]

With his graduate studies still uncompleted, Eckbo had already received validation through publications in leading art and design journals.

Collective Landscapes

During his time at Harvard, Eckbo collaborated with architects and planners, sowing the seeds for his continuing interest in the greater sphere beyond the limits of the individual lot and garden. A project for a recreation center in South Boston, designed with architecture students Saunders, Robinson, Currie, and Crain, suggested the super-structure for public space assigned to varied use.[57] This expanded scope of inquiry was further developed in his thesis study Contempoville, which portrayed Eckbo's vision for the ideal American suburb: a subdivision linked to an imagined 1945 world's fair in Los Angeles. Troubled by the valuing of individual expression over community good, Eckbo proposed a total landscape linked by pervasive rows of hedges reinforced by tall trees [figure 23]. Each family received its own domestic compound, each its privacy ensured by untrimmed hedges. Each site acknowledged its boundaries and yet appeared to develop centrifugally from the interior of the house. The planning idea held consistently throughout, yet Eckbo again used a remarkable variety of formal vocabularies for the designs of the gardens. Oval beds; skewed plantings of hedges; networks of interlocking paths—all these ground patterns were complemented by the higher masses and canopies of trees, composing the domestic space outdoors in three spatial levels. Eckbo's explanatory text read:

23

Contempoville. Study for the overall site plan. Student project at Harvard University, 1938.

Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

House and garden developed as an organic unit which will present a compelling setting for the "more abundant life." The garden flows into the house; the house reaches out into the garden. . . . Nature will dominate these gardens because the plant material is so placed that it can continue its growth with a minimum of interference by the hand of man .[58]

This statement is remarkably prescient in summarizing Eckbo's regard for the single-family site and its relation to the community, and the relation of planned nature to its maintenance and growth.

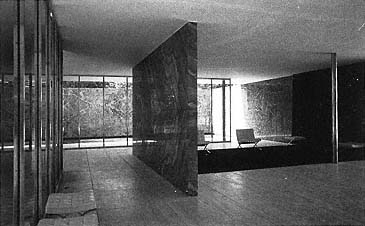

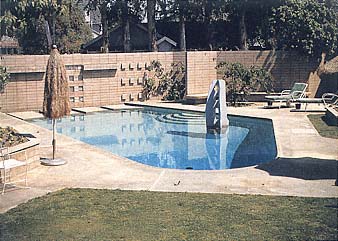

Contempoville's layout employed the winding roads common to the American suburb, with a central park area that could be traced back to the common of colonial times. The suburb's subdivision and design, however, clearly reflected more advanced planning ideas, such as those of Clarence Wright and Henry Stein. Each of the house plans were designed by "real architects" and taken from professional publications;[59] the Barcelona Pavilion made a cameo appearance as the social center of the plan, its reflecting pool adapted for the more mundane function of swimming. The structure's flowing spaces were joined to an amphitheater on one side by sinuous plantings of hedges; a tennis court abutted the buildings' eastern walls. Given the age of its designer, and the scope of his landscape designs executed until this time, the project evinced an astonishing cohesion from site plan to detailed garden plans. The specific vocabulary employed at Contempoville would be loosened in the succeeding decades. But in many respects—foremost among them the ideas of linkage, the group, and the individual home—would stay as constant foundations for almost all of Eckbo's community plans.

Although Contempoville was a more comprehensive and ultimately more significant exercise, it was the Small Gardens in the City project that announced to the architectural readership Eckbo's arrival as a professional with advanced ideas about modern landscape design. Its republication in France, and its inclusion in Margaret Olthof Goldsmith's 1941 Designs for Outdoor Living , reiterated the power of the ideas and the hunger for a new view of landscape architecture.[60] In some ways, Eckbo seems to have already cut his connections with landscape architecture as it had been conceived and as it was prac-

ticed. Here was a vision more compressed and fitted to contemporary conditions and aesthetic developments, aimed at the city more than the estate of the wealthy client. Eckbo's use of publications reveals an incredible drive for soap-boxing, self-promotion, and astute utilization of the print medium. Indeed, he would become a prolific writer, with six books and countless articles published over half a century.

A Graduate Again

Through Frederick Gutheim, whom Eckbo met at Harvard, Mr. Eckbo went to Washington [figure 24]. His courtyard plans for the United States Housing Authority were less specific solutions to specific problems than studies that tested the range of possibilities for developing exterior recreational space [see figure 86]. We see here the furthering of the Contempoville and Small Gardens ideas, or the selective adoption of elements first proposed there to define spaces for sitting, conversation, light work, and play (on the drawings termed "preschool: active; adult: passive"). By applying the spatial ideas of buildings such as the Barcelona Pavilion [figure 25]—in which walls slide past one another, Eckbo created fluid spaces assigned to specific purposes, without sacrificing a sense of the whole. Vegetation was restricted, its use intended to soften the architectural lines over time: "Few shrubs or small plants are indicated and a minimum amount of planted area is called for. Trees, hedges and permanent outdoor structures are the principal elements added to the site."[61] The short tenure in Washington also provided him the opportunity to design a garden for the Gutheims' Georgetown home.

The preliminary design for the Gutheim townhouse garden is dated 10 October 1938 [figure 26]; it could be taken as a collage of the attitudes and motifs proffered in the Small Gardens project.[62] The plan of the long narrow lot was developed along a path that alternated between a flowing biomorphic line and the zigzag borrowed from Pierre-Émile Legrain. Terrace and stair connected the second floor directly to the garden, enclosing a sunken court to the north of the house, cool in summer. The movement from interior to the raised giardino segreto centered on an existing catalpa at the opposite end of the site. The presence of the hidden garden was revealed by a small pool animated by a jet, a structure for tea roses, a perennial

24

Garrett Eckbo in cap and gown.

Harvard University Commencement, 1938.

[Documents Collection ]

25

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. German Pavilion [reconstruction].

Interior view looking toward court. Barcelona, Spain, 1929.

[Marc Treib ]

26

Gutheim garden. Preliminary plan. Georgetown, Washington, D.C., 1938. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

27

General Motors Pavilion, New York World's Fair. Study for the landscape design, 1938. Photostat.

[Documents Collection ]

border, Irish yews, and a host of other more architectural features such as seats and an arbor. The design was far more complex than its site demanded—or even comfortably allowed. It demonstrated how restlessly Eckbo was chafing at the bit, raring to apply as many of his recently developed modernist garden ideas to whatever commission came his way. But he would have to wait; the scheme was realized only in part.

For a short time thereafter, again through Gutheim's auspices, Eckbo worked in the office of Norman Bel Geddes. His assignment there was the landscape design for the General Motors Pavilion for the 1939 New York World's Fair, in particular, the area surrounding the building's principal facade [figure 27]. Modeling the ground plane as a series of earthen terraces and using tree plantings to articulate a series of green zones, Eckbo attempted to complement the building's streamlined masses in landscape form. For Eckbo, this was time to play and explore—in theory, Bel Geddes was interested in advanced landscape ideas to match the architecture of the pavilion. But the final scheme, the one witnessed in photographs of the fair, focused on the procession of visitors who wound their way up the ramps on the pavilion's flank. Little vegetation was used; the reality of the pavilion was the exhibit within.[63] In the end, the Eckbo landscape proposals had come to naught, except to provide the young landscape architect and his wife with sufficient funds to return to California. They did so at the end of 1938.

Return of the Prodigal

"Why don't you go on west to California?" said the "owner men" in John Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath: "There's work there and it never gets cold. Why, you can reach out anywhere and pick an orange. Why there's always some kind of crop to work in. Why don't you go there?"[64]

Like the Joad family, Garrett Eckbo was lured back to California not only by nostalgia but also by the promise of a job—in the Farm Security Administration (FSA ) office in San Francisco. When Eckbo arrived late in 1938, however, the position had evaporated. He sought work from Thomas Church and was taken on immediately. Their association as employer and employee did not last long—two

weeks to be exact. At that time, the FSA job rose again with the promise of slightly greater pay. Eckbo asked Church to match the FSA offer; Church declined, and Eckbo entered the ranks of government functionaries. Filled with advanced landscape design ideas, social ideals, and a considerable population of migrant farmworkers for which to design, the recent graduate joined a talented team of designers working in the FSA 's western office.[65]

Regionalism, with the reexamination of the locale, was a theme underlying many New Deal programs, from the Federal Writer's Project to local art programs. Regionalism asserted the knowledge and experience of a particular place over a broader idea of the nation as a whole, expressing "the need for a sense of place amid the stress and dislocation of the depression." For an agricultural society in turmoil, with hundreds of thousands of displaced nomads forced to wander on western roads, the idea of soil, roots, and home became a preoccupation. "This land, this red land, is us," wrote John Steinbeck, "and the flood years and the dust years and the drought years are us." In the flight that followed dispossession, farmers dreamed of the land from which they had been driven: "How'll it be not to know what land's outside the door? How if you wake up in the night and know—and know the willow tree's not there? Can you live without the willow tree? Well no, you can't."[66]

The regard for things regional exerted an essentially conservative—in its literal sense—influence upon art and design, denying continental avant-garde imports for themes validating what were believed to be distinctively American concepts. The reconstruction of Williamsburg, the elevation of Mt. Vernon to the status of shrine, and the FSA photographic project reveal common origins in the search for heritage. It was an urge that also found expressions in landscape design and buildings that evoked the perceived stability of prior eras, such as the structures based on local historical prototypes built by the National Park Service.

Throughout the country, projects for parks and recreational facilities, rose gardens and campgrounds challenged landscape designers to maximize the impact of minimal means and the often unskilled labor force of the Civilian Conservation Corps. The designs tended to reflect regional themes grounded in sentiment. Park and Recreation

Structures , a three-volume handbook written by Albert H. Good and published by the National Park Service in 1938, represented the best of local and federal governmental sponsored work, from signing and water fountains to lodges and trailer camps. It became the standard reference work for decades. In the foreword to the first volume Arno Cammerer, director of the National Park Service, established the prerogatives for park design:

A basic objective of those who are entrusted with development of such areas [modifications of the natural landscape] for human uses for which they are established is, it seems to me, to hold these modifications to a minimum and so design them that, besides being attractive to look upon, they appear to belong to and be a part of their settings .[67]

Although this statement could be interpreted and utilized by an architect such as Frank Lloyd Wright to produce Taliesin West, for the most part the illustrations and message of the books argued for a traditional expression drawing upon indigenous architecture and materials. "More than any other regional issue," wrote Michael Steiner, "sense of place offered a promise of order, security and self-understanding."[68] Eckbo never denied the importance of these longings, but he did not readily accept the assumed prescription of a regional or traditional expression for them so common to the National Park Service.

Among its assignments, the western office of the Farm Security Administration was charged with providing minimal living conditions for agricultural workers, both migrant and more sedentary, focused on California, Arizona, and Texas. To meet the constantly increasing demands for housing, the authority's designers created a series of camps, many of them in California's Central Valley, that used almost every available form of housing stock. The solutions ranged from tents to trailers to metal sheds; none of them fancy, all of them minimal. These were all standardized units—despised by the program's architects—and the contributions of the FSA designers were primarily in the planning of the communities and in the humanization of exterior spaces against the harsh climates of the arid land.

Eckbo worked on the design of almost fifty camps during his four-odd

28

Park and community building. Harlingen, Texas, 1940. Farm Security Administration. Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

years with the administration, relying on a relatively stable approach to layout and landscape. While many projects, such as the Taft or Shafter camps, used a hexagonal or modified hexagonal arrangement, some schemes were less formal and developed more directly from local site conditions. The designers planned an architectural ecology of sorts, in which platform tents or trailers would be succeeded by more permanent metal housing, probably of little actual improvement given its poor insulative qualities. Finally, apartment blocks or detached houses might be built [see plate II].

In these projects, as in most of his community landscape designs, rows of trees or hedges reduced the velocity of winds and provided shade; their linear alignments or sinuous curves unified the spaces surrounding individual structures, in effect creating a landscape super-structure to which the minimal buildings were subservient. Plant lists were surprisingly varied, with most of the trees brought to the site, others transplanted within the same site or from other proximate FSA projects. These included cottonwood, Chinese elm, sycamore, mulberry, and other hardy species.

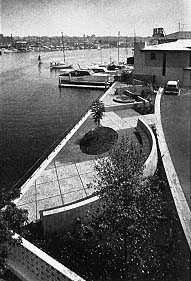

The highlights of the landscape schemes were the park or community areas in which the group spaces of laundry structures, meeting rooms, or playgrounds were extended outward [figure 28]. In Landscape for Living , Eckbo presented twelve variants for the same park space for the camp near Weslaco, Texas, demonstrating how to create genetically affiliated spatial designs using a simplified—yet consistent—vocabulary [see figures 98, 99]. All these areas were intended to be irrigated and kept green. Water resources were usually available because the camps occupied sites previously used as farms or ranches. In some instances, the grand ideas—both social and vegetal—languished with lack of maintenance. Dorothea Lange's photographic documentation made the limits of the FSA 's interventions only too clear, discussed by Dorothée Imbert in the following essay.[69]

In retrospect, the success of the FSA projects might be qualified, but rarely the idealism of their enterprise. Housing by Burton Cairns and Vernon DeMars at Chandler, Arizona, and Yuba City were among the earliest social housing in the United States, cited and published widely. The landscape ideas that complemented these projects—led

by Garrett Eckbo and his classmates Corwin Mocine and Francis Violich—matched in energy and zeitgeist the most advanced of architectural ideas. In almost all of these landscape designs, the spatial ideas found in Modernist architectural space were applied to desiccated landscapes or agricultural fields. Versions of Eckbo's Contempoville were realized up and down the length of California, reduced to an almost pathetic level of means, but with no reduction in the intensity of their spatial investigation or humanity.

During his employment with the FSA , Eckbo moonlighted on private commissions and took an active part in the discussion of relevant professional and social issues. Telesis, an informal alliance of design practitioners based in San Francisco, was formed to address the problems facing the environment of the Bay Area. The first meeting was held in the Eckbo house on Telegraph Hill in 1939, with a core group that included architects Burton Cairns, Vernon DeMars, and Phillip Joseph; planner T. J. Kent; landscape architects Francis Violich and Corwin Mocine (who would become planners); and industrial designer Walter Landor, among others. In July 1940 the group held an exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Art, arguing for comprehensive planning, the joining of social, political, and physical planning concerns, and an integration of the design professions in outlook and collaboration. Although Eckbo served as editor of a West Coast issue of Task in late 1944, the group's cohesion—if not its idealism—had been seriously undermined by the demands of war, at home and in battle.[70]

With the American entry into World War II, the FSA agency turned its attention to defense workers' housing for their constantly growing numbers in the San Francisco Bay Area and central California. Of the existing government agencies, only the FSA held a positive track record for producing housing and community facilities, on time and more or less on budget: "Neither [the United States Housing Authority nor the Public Buildings Administration] was very effective, and by the spring of 1941 the housing program was the furthest behind schedule of all defense building efforts."[71] The result was the FSA 's undertaking of defense workers' housing and the formation of the Division of Defense Housing to meet the ever-growing population surges into California.

The War Years, The Postwar Years

The lingering effects of a 1939 auto accident, in which Burton Cairns was killed, kept Eckbo from active military service.[72] And a few weeks' work in a Sausalito shipyard convinced Eckbo that his talent lay in design; he went to work for the war effort, planning four dozen schemes within a three-year period. The site and landscape development for the community and commercial center in Vallejo, designed by Theodore Bernardi and Ernest Kump, paralleled designs by Thomas Church for housing by William Wurster on other parts of the site. The means were meager; the allotted time, virtually none. Once again, sinuous lines of poplars doubled as spatial integrators and windbreaks, softening the relentless march of standardized units that followed the contours of the grassy hillsides.

With hostilities ended in August 1945, America began the return to normalcy. Given the transplanted minions of workers who elected to remain in the Golden State, the GI Bill that gave veterans access to education and homes, and the basic optimism that accompanied the nonmartial economy, California boomed. Suburbs developed on the perimeter of every major city in the state, soon to be rendered the inside of the city and not its edge.[73] Freeways provided access to greater and greater amounts of land gobbled by suburban development, calling for more freeways and even greater development. The cycle never abated.

Eckbo formed a partnership with his brother-in-law, Edward Williams, in 1940 and designed a number of gardens in the San Francisco Bay Area while employed with the FSA and war housing programs.[74] At a Telesis gathering before the war, Eckbo met Robert Royston, who worked for Thomas Church from the late 1930s until he entered military service. Royston, always known as an extremely talented designer, became a mainstay of the Church office and supervised the defense workers' housing project in Vallejo. By mail, Eckbo invited him to join the firm as partner upon his release from the Navy, where he was serving in the Pacific theater. Royston had come within a hairsbreadth of partnership with Church: "When I got home Tommy had my name on the door. It was a difficult period for me

because I liked Tommy very much and we had a close relationship. But Garrett always attracted me because he's a clear and social thinker, and he can really see the whole picture." He described practice as a brand-new world where "we could experiment right and left."[75]

Eckbo, Royston and Williams was established in 1945, and within five years it had become one of the leading firms in the country, highly regarded for its advanced planning ideas, innovative modern vocabulary, and its quality of execution. It was during these years that the distinctive Eckbo idiom developed, prompted by the association with Robert Royston, and in collaboration with leading architects such as Joseph Stein, John Funk, and John Dinwiddie. To some degree, these designs developed ideas first proposed in the Small Gardens and Contempoville studies, but each of these ideas was tempered by the particular conditions of the site and program.

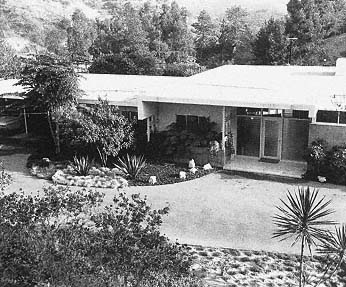

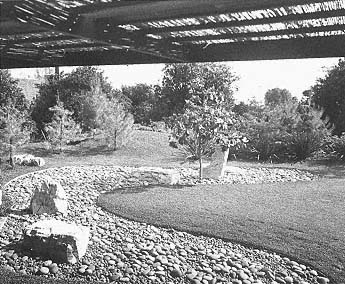

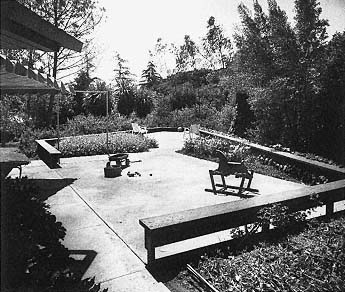

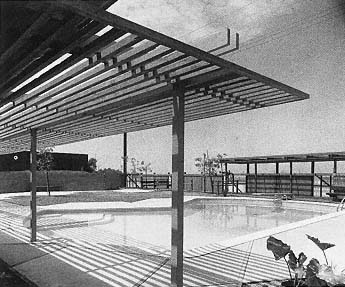

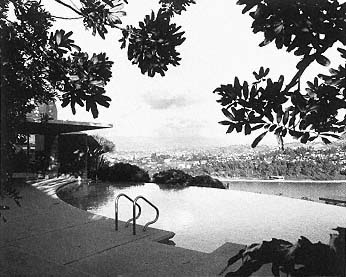

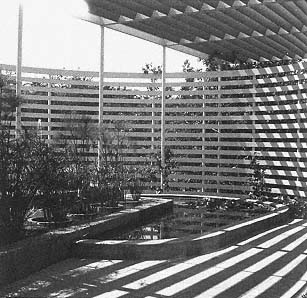

The 1939 garden for Mr. and Mrs. F. M. Fisk in Atherton had allowed Eckbo to work at larger residential scale, pairing sunny lawn and "natural meadow" areas with layered spaces defined by hedges, set under oaks and redwoods [figures 29, 30]. The net effect was one of openness and enclosure, sun and shade, boundary and vista. That no aspect of the garden was perceived as absolute is also suggested in a pencil study for the Reid garden in Palo Alto from the same period [figure 31]. The low hedges established an orthogonal structure in which the house reverberated in the garden; but the overarching frame of trees led the eye over and beyond these spatial dividers toward the horizon. For John Dinwiddie's 1941 Frazier Cole house in Oakland, Eckbo used curving planes of wooden screen walls to enclose fluid spaces around the house, protecting them from unwanted street noise and outside view [figures 32, 33].

As a group, the designs for northern California gardens of the period following immediately after the war could best be characterized as considerate of their clients' needs and the dicta of the site, and intelligent in deriving forms to suite those requirements. Although touches of modernity appear in their spatial definition, in the curving of a wall or in the use of some offbeat paving material, the gardens

29

Fisk garden. Site plan. Atherton, 1939. Photostat.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

30

Fisk garden. View southwest over the lawn area. Atherton, 1939.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

31

Reid garden, Study. Palo Alto, circa 1940. Photostat.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

32

Cole garden. Axonometric view. Oakland, 1941. Photostat.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

33

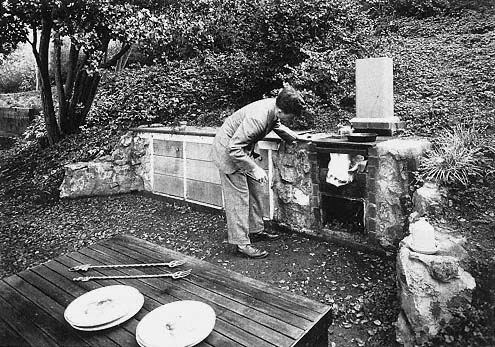

Cole garden. Retaining wall with built-in barbecue—and Garrett Eckbo. Oakland, 1941.

Photostat. [Philip Fein, courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

34

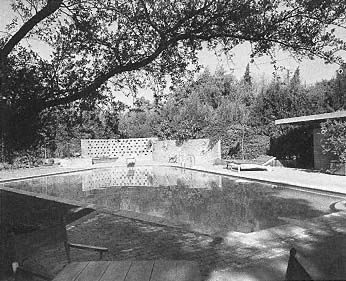

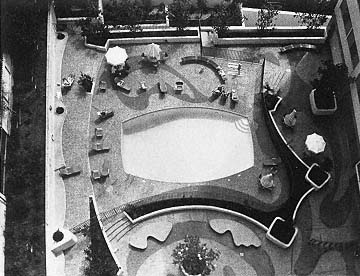

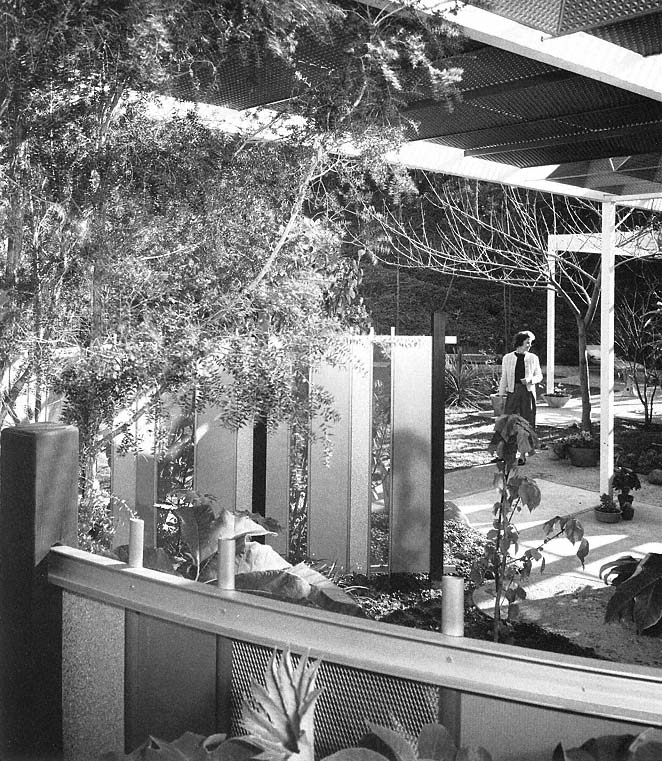

Robert Royston. Platt garden.

Axonometric view. Oakland, circa 1946.

[ from Architect and Engineer]

35

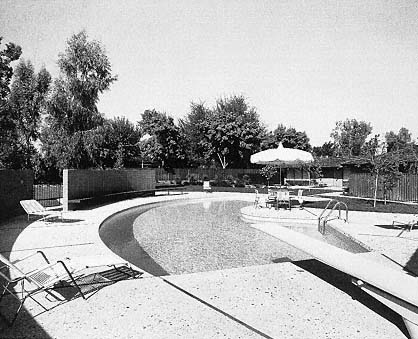

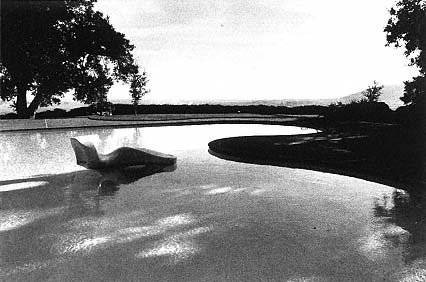

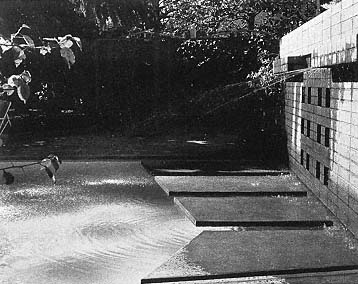

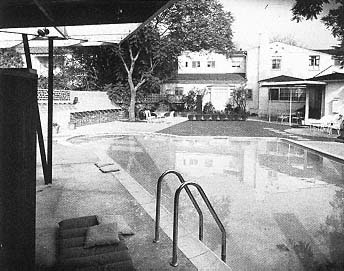

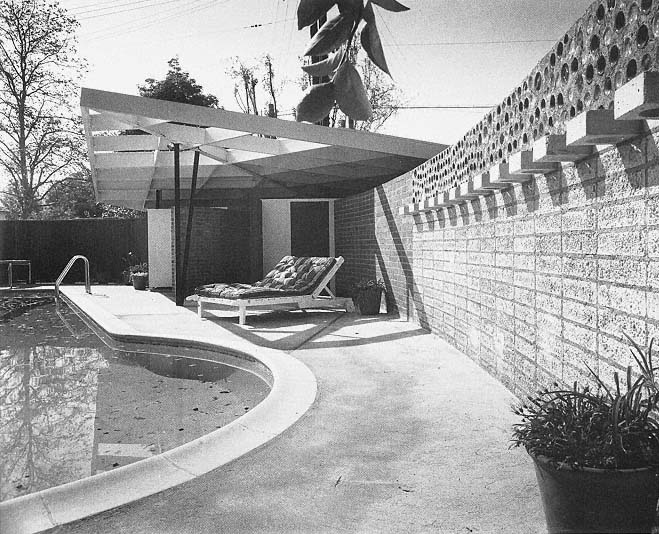

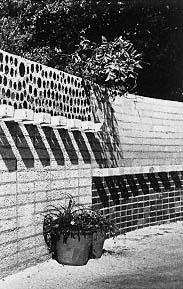

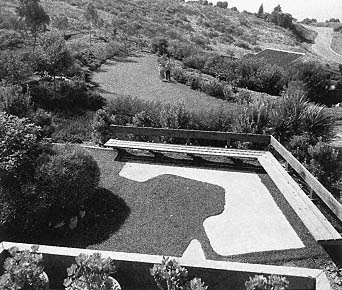

Robert Royston. The Palo Alto. Pool area. Palo Alto, 1950s.

[Louis Alley, courtesy Robert Royston ]

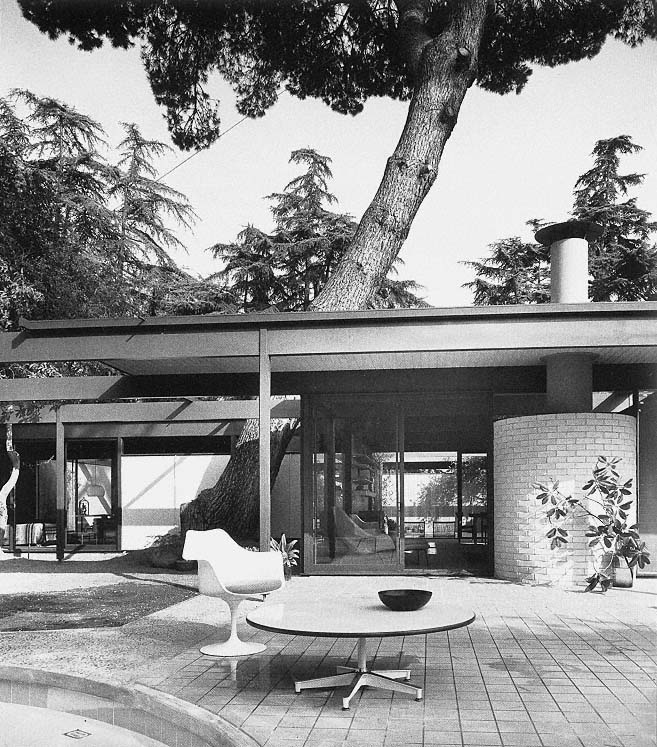

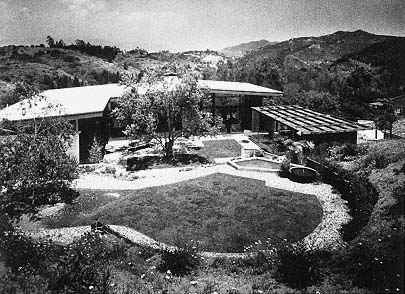

remained polite and restrained, lacking the full-blown exuberance of the following years in southern California.