Emergency Landscapes

Between July 1940 and July 1943 at least three million workers had moved to sustain the ship, airplane, and munitions industries; with their families, the displaced masses totaled about seven million people.[54] They urgently required living accommodations. Name-brand architects contributing to the landscape of defense housing included Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, Eliel and Eero Saarinen, Buckminster Fuller, and more locally, William Wurster.[55] California's population increase made "the once famous Grapes of Wrath problem look like a picnic," stated the planning and housing expert Catherine Bauer.[56] Recognized for its efficient provision of emergency housing, the FSA had shifted its focus from migrant laborers' assistance to defense housing by 1941 [figure 109]. Eckbo served as landscape consultant for about fifty of these war housing projects. The socially and architecturally radical—and somewhat quixotic—efforts of the FSA era were definitely over as the government turned on its own. In 1942, before leaving the relief administration, Eckbo worked on developing camps for "Japanese evacuees" in the Owens Valley. His projects include the landscape plan for the staff housing section of Manzanar, a relocation unit for Japanese Americans. The camps of Marysville and Tulare originally destined for workers from the Dust Bowl, now served as temporary internment quarters.[57] Eckbo had joined the FSA to formulate a sheltering landscape for the displaced and landless; now

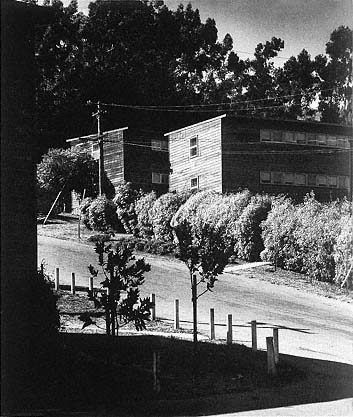

109

Defense housing trailer park. San Miguel, 1942. Farm Security Administration.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

—however tragically—the relocation centers served as a mean of pure control, and instead of offering a sense of place reprieved from the outside world, they brought only a sense of isolation.

Eckbo had applied the lessons of high art, first advanced in the Contempoville project, to the basic functionalism of the FSA camps. In a similar way, he would learn from his experience with defense housing and trailer camps to establish a pattern for postwar suburban developments. As he would later write in Landscape for Living:

The general theory is the grouping of the units in articulated cellular patterns in which the cells achieve special identity by virtue of the strong formal relations established within them. The total grouping achieves a spatial organization of the site with considerable movement and quality. Tree patterns and building colors can of course expedite this identifying articulation a great deal .[58]

Eckbo's contribution to FSA California war housing included the landscape plan for 72 units at Taft, designed by Vernon DeMars, and that for 3,000 single Navy workers and 200 families at Vallejo, with Theodore Bernardi and Vernon DeMars [figure 110]. Like Thomas Church's vegetal solutions for emergency landscapes, Eckbo's scheme for Vallejo attempted to provide neighborhood identity while relieving the rigidity of the matter-of-fact site plan. He relied on windbreak allées of Lombardy poplars and weeping willows to edge the various clusters of cabins, dormitories, restaurant, and administration buildings. He interspersed this formal order with specimen plantings of Japanese privet, sycamore, and Pittosporum nigricans , much as he had keyed the various areas of migrant camps with vegetation. The same ideal underlay FSA projects and war housing as "every technician involved in developing environments for people is responsible not just for providing shelter, but also for developing their fundamental potential dignity" [figure 111].[59]

Eckbo argued for planning defense housing without "the sacrifice of essential space to the twin bogeymen of cost and mechanical gadgetry, [nor] the vicious practise of developing minimum standards based on income strata, rather than optimum standards based on bio-ethnic needs," which he foresaw as "too apt to produce the slums of tomorrow."[60] In this deprecation of the Housing Authority's stan-

110

Defense housing "duration dormitories" and cabins for Navy yard workers. Site plan. Vallejo, 1942.

Farm Security Administration. Tenant activities building seen in the upper segment of the site plan

was designed by Bernardi, De Mars, Wickenden, Langhorst, and Funk.

[Documents Collection ]

111

Defense housing dormitories. Sausalito, 1946.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

dards, he echoed Catherine Bauer's assertion that public housing and even more so, war housing, allotted too little space to both interiors and exteriors. This was a stance that Eckbo shared again, when he deemed that after the sacrifices of the war effort, Americans deserved, not minimum, but optimum standards in housing.