A New Deal

The nomads had been the followers of flocks and herds,

Or the wilder men, the hunters, the raiders.

The harvesters had been the men of homes.

But ours is a land of nomad harvesters .[11]

Early in his presidency, Franklin Delano Roosevelt advocated the need for national planning as a palliative to the economic freefall that followed the 1929 Wall Street crash and plagued individuals across the country [figure 87].[12] Planning policies were drafted to establish rural communities that would offer advantages equal to those of urban settlements; to create new towns in undeveloped areas; and to reform land-use and agricultural economic patterns.[13] Ironically, the centralized bureaucracy promoted the most advanced planning ideals through the actions of visionary individuals, as it was forced by stringent time constraints to decentralize, thus relinquishing power and control.

Initiated by the Division of Subsistence Homesteads in the Department of the Interior and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration at the outset of Roosevelt's first term, communities were later developed by the Resettlement Administration (RA ) and finally by the Farm Security Administration [figure 88]. With roots in the socialist theories of Charles Fourier and Robert Owen, the American rural cooperative models of the 1930s further reinforced the back-to-the-land movement initiated at the beginning of the century.

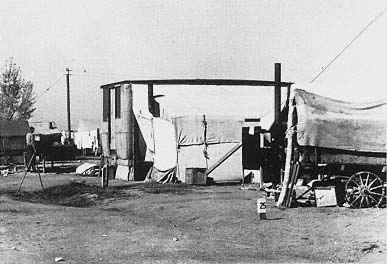

87

"Typical of thousands of migrating agricultural laborers.

California. March, 1937."

[Dorothea Lange, courtesy Bancroft Library,

University of California at Berkeley ]

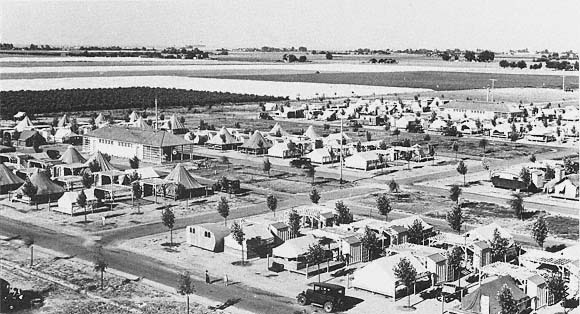

88

Tulare Camp. Aerial view. Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley,

1937–42. Farm Security Administration.

[ from Pencil Points]

This movement had advertised the financial advantages of returning to an agrarian economy in opposition to the evils of industrialization. After the 1929 crash, however, it was the quest for survival rather than better economic prospects that drove hordes of back-to-the-landers out of cities. In his inaugural speech on 4 March 1933, Roosevelt urged Americans to "recognize the overbalance of population in industrial centers and, by engaging on a national scale in a redistribution, endeavor to provide a better use of the land for those best fitted for the land."[14] Eckbo would later denounce this type of sentimentalism while he agreed with the need for the specificity of design standards applied to rural situations.[15]

On 30 April 1935 Roosevelt placed Rexford Tugwell at the helm of the newly created Resettlement Administration, whose goals included establishing communities for destitute or low-income families in rural and suburban areas. Other charges concerned reforestation, erosion control, flood control, rural rehabilitation, and recreational development. We need only review the legacy left across America by New Deal programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC ), the Works Progress Administration (WPA ), the Soil Conservation Service (SCS ), or the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA ) to understand the value of federal planning in the development of public domain. It was the hopelessness of the depression that had both instigated and permitted the intervention of the federal government. By the second half of the 1930s, however, with the likely prospect of future economic recovery, the assisted population showed less tolerance toward the somewhat paternalistic directives of the planned communities. The Resettlement Administration, and later the Farm Security Administration, would pursue relief as well as permanent reform. The RA 's ambitious mission was caustically described by a journalist as attempting "to rearrange the earth and the people thereof and devote surplus time and money, if any, to a rehabilitation of the Solar System."[16] Even the basic relief of migratory camps was met with loud protests from the growers, who feared that the concentration of a semi-permanent labor force would permit organization.[17] Thus large-scale farmers and farm organizations hardly viewed the system of grants and loans that allowed individual farmers and cooperatives to gain ownership of land as a necessity. Both relief administrations would be vilified by powerful agricultural lobbies as harboring Communist tendencies.

89

A Hooverville.

[Dorothea Lange, courtesy Bancroft Library,

University of California at Berkeley ]

The National Labor Relations Act, signed into law by Roosevelt in July 1935, precluded agricultural laborers from the rights and protections guaranteed to industrial workers. The westward displacement of farmers from the southcentral states—Oklahoma and Arkansas in particular—exacerbated the meager conditions of the rural caste and brought the New Deal Administration and its emergency relief programs to the field of migrant housing and health. Forced off their farms, hundreds of thousands of refugees from the so-called Dust Bowl flowed into California. The field reports prepared by the economist Paul Taylor and illustrated by Dorothea Lange's photographs publicized the plight of white migrant workers and shocked an America that had otherwise remained oblivious to the equally unfortunate working and living conditions of Mexican, Asian, or black laborers.[18] Settling mostly in the Central Valley, the new wave of temp-farmers lived along roads, in private labor camps, overcrowded auto and trailer camps, shack towns, and squatter camps [figure 89]. With Tugwell's resignation, the controversial Resettlement Administration was reborn in September 1937 under the guise of the Farm Security Administration, with Will Alexander at its head. The new agency carried on the work and planning ventures of the Resettlement Administration, placing an emphasis on the aid to the lowest stratum

90

Chandler Co-operative Farm housing. Southwest garden facade

(oriented toward prevailing breezes). Arizona, 1936–37, 1939.

Farm Security Administration. [Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

of farmers, found in the migrant laborers of California and the Southern sharecroppers.[19]

Perhaps in reaction to the criticism of Tugwell's excessive power and control, the twelve regional offices of the FSA operated independently of the parent agency in Washington on all matters except final approval of designs and cost. This lack of bureaucratic interference paired with an absence of precedent allowed the regional offices to act locally and experiment with architectural and landscape design, site planning, and engineering. Talbot Hamlin, tireless proselytizer for modern American architecture, described the FSA communities as "human and attractive because their designers understood people and their needs, and insisted that all those needs—intellectual and emotional as well as physical—should be taken care of. They are beautiful because designed by artists, to whom creation was not limited by any economic deadline and to whom it was as necessary to think in creative form terms of a privy as of a community center."[20]

The planning production of the San Francisco FSA office was somewhat codified: hexagon-shaped camps in California (Tulare) as well as in Arizona (Eleven-Mile Corner); modernist prisms of multi-family units in adobe were erected at Chandler, Arizona, and in wood and

91

Tulare Camp. Aerial view of multi-family housing units, with trailer

camp in the background. Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley,

1937–42. Farm Security Administration.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

92

Taft Defense Housing. San Joaquin Valley, 1941.

Farm Security Administration.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

composition board at Yuba City, Tulare, and Taft in California [figures 90–92]. This rationalized planning addressed a typical function—the relief of day farmers and their families. Atypical, however, were the time frame of construction and life span of these facilities. Intended as emergency solutions to a temporary crisis, they were conceived as instant towns that would probably never mature and whose surreal character must have rivaled that of movie sets propped up in the middle of the desert.

Ironically, the social underpinning of the FSA venture, at least for the San Francisco office, generated an approach to architecture whose formal stance would be recognized internationally. Thus the cooperative farm of Chandler, for example, which Vernon DeMars and Burton Cairns planned and designed, was selected as one of the two examples of American modern architecture to illustrate Alfred Roth's Die Neue Architektur 1930–1940 .[21] Roth duly highlighted the design's response to climatic and functional constraints: the housing units were set at an angle to the road and at a right angle to the prevailing winds, so as to maximize their cooling capabilities. Adobe offered thermal advantages; its labor-intensive, self-help construction process provided work for the unemployed; and its traditional roots tied the buildings to the vernacular. The lower units were shaded by the first floor overhang, itself protected from direct sunlight by a protruding roof.

Roth also recorded the various landscape additions to this flat site, which before agricultural irrigation "was a cactus-covered desert." The kitchen-dining room extended outward, into the individual garden, under the shade of a poplar (albeit a strange choice for a shade tree). The garden was designed almost as if it belonged to a standard urban lot, in its elongated dimensions as well as in its features. The "sitting out place" was bounded by hedges, fragrant with herbs, and decorated with geranium, morning glory, and rockrose; the clothesline ruled over the lawn patch and a fruit tree marked the limits of the lot. Such mundane—yet elegant—arrangements revealed the importance of landscape as a common denominator within a wide spectrum of cultural origins. Everybody everywhere needed a tree, especially when "everywhere" was not home. Thus vegetation acted as an anchor to the land. It was both universal and traditional. Because of such features, Eckbo's efforts to create an indigenous

and formally innovative lexicon for the migrant camps were particularly noteworthy.

93

Shafter Camp. Tents on platforms with trellis extensions.

Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley, 1938. Farm Security Administration.

[The Dorothea Lange Collection, The Oakland Museum of California, The City of Oakland .]