The Art of Social Landscape Design

Dorothée Imbert

For almost six decades Garrett Eckbo gave form to our landscape. The scope of his contributions ranged from small sculptural gardens to large-scale planning schemes; his practice evolved from a home-based studio enterprise to a multi-initialed corporation. Eckbo's commitment to aesthetics, laid upon solid social foundations, never wavered. To the self-posed rhetorical questions—Is design social? and Is it art?—he replied, "Formal design can be socially oriented and social design may be art. Regardless of form concepts, the basic question may be: is design for people, or are people a vehicle for design?"[1]

From the outset of his career, Eckbo treated plants both as units of construction and as conductors for social patterns, whether they structured the private realm or the collective landscape. No matter how elite, his gardens were always considered to be arenas for living, rather than mere pictorial compositions. Perhaps even more remarkable was his double dedication to create a new form of community life and instill beauty in the landscapes for the landless laborers of the depression. William Wurster, architect and longtime collaborator of Thomas Church, commended architects who "chose to work for the Government," in particular Burton Cairns and Vernon DeMars, for their design of the Farm Security Administration migrant camps in California. Wurster assessed camps as "minimum shelters for human beings [that had become] 'architecture.'" With such endeavors, he

Garrett Eckbo. Southern California, circa 1946.

[Documents Collection ]

continued, "the design of buildings emerged as a social art, and [he] hope[d] it will never be placed exclusively on the luxury shelf again."[2] Similarly, Eckbo's contribution to the New Deal landscape remains an extraordinary conjunction of high design, or art, and true understanding of social exchanges—and people.

The projects Eckbo conceived for the Farm Security Administration mark the first concrete manifestation of his involvement in designing the collective landscape. Student projects and early publications had already demonstrated the telltale signs of a growing social conscience. His writings from 1938 onward are informed with an awareness of the disproportionate distribution of wealth, the tension between aesthetics and functionalism, and the delicate balance between planning for the demands of the individual and those of the group.

Ground Work

For almost six decades Eckbo gave form to our social landscape. He continuously framed his theories and social ideals within the search for a modern idiom, establishing a perpetual dialogue among people, nature, and aesthetics. With his Harvard fellows Dan Kiley and James Rose, Eckbo published articles that stressed the necessity for a revised approach to landscape design, whether for an urban, rural, or primeval situation. Echoing Christopher Tunnard, the triumvirate of modernist graduate students argued for the application of science to the field of landscape design and for the use of vegetation sculpturally, if not structurally. As if to announce Tunnard's 1942 claim that the "right style for the twentieth century is no style at all, but a new conception of planning the human environment," Eckbo repeatedly stated the irrelevance of style to landscape design.[3] Instead of deepening the schism between formal and informal styles, he asserted, one should seek a dual understanding of biology and geometry. Abandoning the classical references of his early student investigations, such as An Estate in the Manner of Louis XIV designed while at Berkeley [see figure 2], Eckbo's Harvard projects veered decisively toward modernism. The 1937 Freeform Park was a "Memorial to the Fathers of our Country" situated on Potomac Island, where the informal became modern, and the modern went informal [see figures 10–11; plate I]. If the circulation and general geometries of Freeform Park still retained a traditional structure reminiscent of Fletcher

83

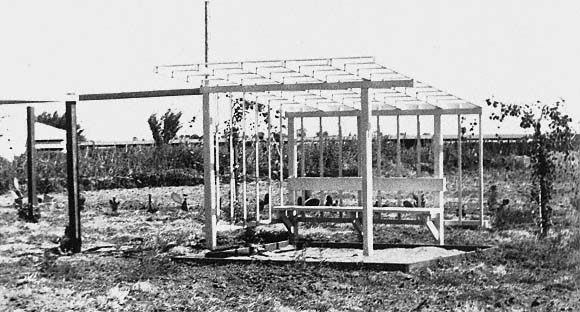

Flexible Co-op (project). Circa 1945. The adjustable screens facilitated the transformation

of private space into public.

[Documents Collection ]

Steele's classical modernity, two of Eckbo's later student projects clearly departed from such references.

For the 1937 Small Gardens in the City, Eckbo shaped the backyards of an entire urban block [see figures 21, 22a-d]. Although he designed most of the gardens as individual entities, the play of partition walls affecting two neighboring lots announced his future explorations in site planning. The postwar Flexible Co-op project, for instance, structured the garden in gradients of privacy: as one moved away from the house, the space remained private or became semi-public through the manipulation of boundaries—hedges and movable screens [figure 83].

Eckbo's thesis project, Contempoville, also studied the formal variations of individual residential gardens but added a public dimension with a central communal open space [figure 84]. His proposal situated Contempoville in Los Angeles, at the time of a hypothetical 1945 world's fair, which would have "portray[ed] the World of Day-After-Tomorrow [through] an exposition of the most advanced design-thought of the day." To answer the wishes of his client, Eckbo developed a block of model suburban homes composed of twenty-three houses, whose plans he borrowed from contemporary architectural magazines, placed on half-acre lots around a ten-acre park. The park offered "active recreational facilities" for residents of all ages, thereby leaving money and space for a "more pleasing landscape development" of individual lots.[4] The garden plans were extremely varied but consistent in the modernity of their idioms [see figure 23]. Arp-inspired biomorphic shapes, replicas of Legrain's zigzag lawn border [see figure 13], and explosions of angled lines shaped the ground plane. Similarly, enclosing elements and sylvan architecture manipulated the spatial envelope. By alternating translucent and opaque walls, and hedges above and below eye-level, Eckbo confused the sense of boundary and implied a continuation of the dynamically layered space into the depth of the park. A caption read: "Beginning with geometrical lot lines and house forms, shrubs and trees are placed in a consciously ordered arrangement to control the garden space. However, nature will dominate these gardens, because the plant material is so placed that it can continue its growth with a minimum of interference by the hand of man."[5] Such divorcing of the graphic ground plane from the vegetal mass foreshadowed Eckbo's landscape

84

Contempoville: A Model Block of Suburban Homes, to be exhibited

at the Los Angeles 1945 World's Fair. Site plan. Thesis project, Harvard University, 1938.

[Documents Collection ]

85

Contempoville. Central park with shelter (replica of the 1929 Barcelona [German] Pavilion),

outdoor theater, and playgrounds. Plan. Thesis project, Harvard University, 1938.

[Documents Collection ]

compositions for the migrant camps, as well as his planned communities in southern California, where the volumetrically varied plantings effaced the rigor of their arrangement.

The communal amenities of Contempoville included an outdoor theater, children's playgrounds, tennis court, swimming pool, and its shelter [figure 85]. Centrally placed within the block, these were arranged inside groves of trees and partitions of hedges. For the pool shelter, the landscape architect borrowed Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's 1929 Barcelona Pavilion [see figure 25], which—in Eckbo's own words—had thus "achieved (or descended to) functional community use."[6] If the transformation of this icon of modernist architecture—witnessed in the revision of the reflecting pool into a swimming pool—may seem irreverent to some, the homage to Mies was genuine. Seeking the concept of house-and-garden as an organic unit, Eckbo cited contemporary architecture for what he termed "decentralized building and open space arrangements, in which one can find no façades."[7] He translated Mies's depth-enhancing overlay of architectonic planes into shifting hedges that suggested unbounded space within the scale of the private garden. Although Eckbo later dismissed Contempoville as falling short of being a community—qualifying his student thinking, not in social or planning terms, but exclusively in formal terms—this project held all the promise of his future investigations in site space design and social involvement.[8]

Formally, Mies van der Rohe's dissolving of the architectural envelope would find literal applications in several of the public landscapes Eckbo conceived just after graduation [figure 86]. He spent half of 1938 in Washington, D.C., designing guideline schemes for public housing recreation spaces at the request of Frederick Gutheim (assistant information director, United States Housing Authority).[9] In these theoretical projects, the vocabulary of Contempoville was further developed, as well as simplified. The shifting and overlapping of planes—hedges and screens, benches, pools, and sandboxes—and architectonic rows of trees defined various use areas, whose rigor was softened by the curvilinear wrappings of grassed islands and tree canopies. Plantings were minimal, to reduce maintenance. Untrimmed hedges partially reinforced the edges of the central space and established a link with the tenant yards. These vegetal screens framed the "free play," "quiet," "shelter," or "apparatus" zones. Regulated by allées

86

Study for public housing recreation areas. Axonometric drawing and plan.

Designed for the United States Housing Authority. Washington D.C., 1938.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

and bosks (which were "transparent," that is not fully blocking the view), architectural partitions (above and below eye level), and hedges (opaque, blocking the view), the space was varied, yet neither confining nor labyrinthine, and thus offered the ideal terrain for the "active pre-school child."[10]

Although Eckbo came from a modest background and had been exposed by osmosis at Harvard to the social ethos of European modernism—in courses offered by Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer—his student years were relatively sheltered from the effects of the depression. Upon his return to the San Francisco Bay Area, however, Eckbo immersed himself in one of the major enterprises of federal relief planning, when he joined the Farm Security Administration (FSA ) in 1939.

A New Deal

The nomads had been the followers of flocks and herds,

Or the wilder men, the hunters, the raiders.

The harvesters had been the men of homes.

But ours is a land of nomad harvesters .[11]

Early in his presidency, Franklin Delano Roosevelt advocated the need for national planning as a palliative to the economic freefall that followed the 1929 Wall Street crash and plagued individuals across the country [figure 87].[12] Planning policies were drafted to establish rural communities that would offer advantages equal to those of urban settlements; to create new towns in undeveloped areas; and to reform land-use and agricultural economic patterns.[13] Ironically, the centralized bureaucracy promoted the most advanced planning ideals through the actions of visionary individuals, as it was forced by stringent time constraints to decentralize, thus relinquishing power and control.

Initiated by the Division of Subsistence Homesteads in the Department of the Interior and the Federal Emergency Relief Administration at the outset of Roosevelt's first term, communities were later developed by the Resettlement Administration (RA ) and finally by the Farm Security Administration [figure 88]. With roots in the socialist theories of Charles Fourier and Robert Owen, the American rural cooperative models of the 1930s further reinforced the back-to-the-land movement initiated at the beginning of the century.

87

"Typical of thousands of migrating agricultural laborers.

California. March, 1937."

[Dorothea Lange, courtesy Bancroft Library,

University of California at Berkeley ]

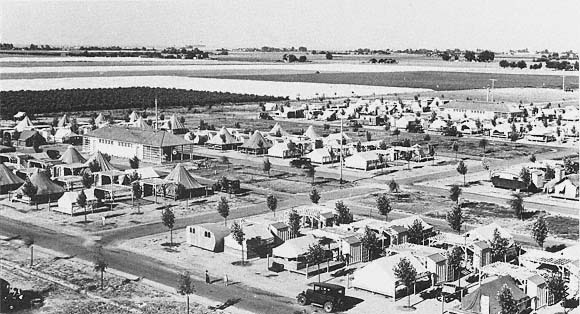

88

Tulare Camp. Aerial view. Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley,

1937–42. Farm Security Administration.

[ from Pencil Points]

This movement had advertised the financial advantages of returning to an agrarian economy in opposition to the evils of industrialization. After the 1929 crash, however, it was the quest for survival rather than better economic prospects that drove hordes of back-to-the-landers out of cities. In his inaugural speech on 4 March 1933, Roosevelt urged Americans to "recognize the overbalance of population in industrial centers and, by engaging on a national scale in a redistribution, endeavor to provide a better use of the land for those best fitted for the land."[14] Eckbo would later denounce this type of sentimentalism while he agreed with the need for the specificity of design standards applied to rural situations.[15]

On 30 April 1935 Roosevelt placed Rexford Tugwell at the helm of the newly created Resettlement Administration, whose goals included establishing communities for destitute or low-income families in rural and suburban areas. Other charges concerned reforestation, erosion control, flood control, rural rehabilitation, and recreational development. We need only review the legacy left across America by New Deal programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC ), the Works Progress Administration (WPA ), the Soil Conservation Service (SCS ), or the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA ) to understand the value of federal planning in the development of public domain. It was the hopelessness of the depression that had both instigated and permitted the intervention of the federal government. By the second half of the 1930s, however, with the likely prospect of future economic recovery, the assisted population showed less tolerance toward the somewhat paternalistic directives of the planned communities. The Resettlement Administration, and later the Farm Security Administration, would pursue relief as well as permanent reform. The RA 's ambitious mission was caustically described by a journalist as attempting "to rearrange the earth and the people thereof and devote surplus time and money, if any, to a rehabilitation of the Solar System."[16] Even the basic relief of migratory camps was met with loud protests from the growers, who feared that the concentration of a semi-permanent labor force would permit organization.[17] Thus large-scale farmers and farm organizations hardly viewed the system of grants and loans that allowed individual farmers and cooperatives to gain ownership of land as a necessity. Both relief administrations would be vilified by powerful agricultural lobbies as harboring Communist tendencies.

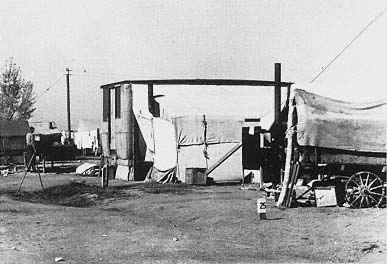

89

A Hooverville.

[Dorothea Lange, courtesy Bancroft Library,

University of California at Berkeley ]

The National Labor Relations Act, signed into law by Roosevelt in July 1935, precluded agricultural laborers from the rights and protections guaranteed to industrial workers. The westward displacement of farmers from the southcentral states—Oklahoma and Arkansas in particular—exacerbated the meager conditions of the rural caste and brought the New Deal Administration and its emergency relief programs to the field of migrant housing and health. Forced off their farms, hundreds of thousands of refugees from the so-called Dust Bowl flowed into California. The field reports prepared by the economist Paul Taylor and illustrated by Dorothea Lange's photographs publicized the plight of white migrant workers and shocked an America that had otherwise remained oblivious to the equally unfortunate working and living conditions of Mexican, Asian, or black laborers.[18] Settling mostly in the Central Valley, the new wave of temp-farmers lived along roads, in private labor camps, overcrowded auto and trailer camps, shack towns, and squatter camps [figure 89]. With Tugwell's resignation, the controversial Resettlement Administration was reborn in September 1937 under the guise of the Farm Security Administration, with Will Alexander at its head. The new agency carried on the work and planning ventures of the Resettlement Administration, placing an emphasis on the aid to the lowest stratum

90

Chandler Co-operative Farm housing. Southwest garden facade

(oriented toward prevailing breezes). Arizona, 1936–37, 1939.

Farm Security Administration. [Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

of farmers, found in the migrant laborers of California and the Southern sharecroppers.[19]

Perhaps in reaction to the criticism of Tugwell's excessive power and control, the twelve regional offices of the FSA operated independently of the parent agency in Washington on all matters except final approval of designs and cost. This lack of bureaucratic interference paired with an absence of precedent allowed the regional offices to act locally and experiment with architectural and landscape design, site planning, and engineering. Talbot Hamlin, tireless proselytizer for modern American architecture, described the FSA communities as "human and attractive because their designers understood people and their needs, and insisted that all those needs—intellectual and emotional as well as physical—should be taken care of. They are beautiful because designed by artists, to whom creation was not limited by any economic deadline and to whom it was as necessary to think in creative form terms of a privy as of a community center."[20]

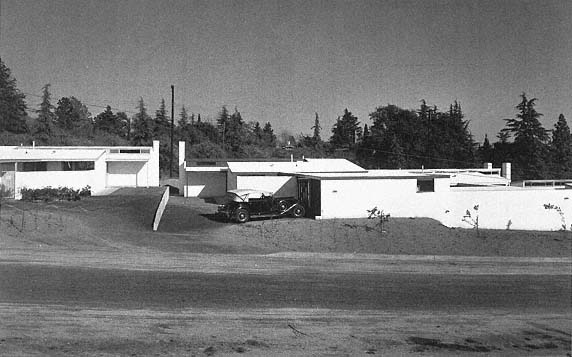

The planning production of the San Francisco FSA office was somewhat codified: hexagon-shaped camps in California (Tulare) as well as in Arizona (Eleven-Mile Corner); modernist prisms of multi-family units in adobe were erected at Chandler, Arizona, and in wood and

91

Tulare Camp. Aerial view of multi-family housing units, with trailer

camp in the background. Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley,

1937–42. Farm Security Administration.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

92

Taft Defense Housing. San Joaquin Valley, 1941.

Farm Security Administration.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

composition board at Yuba City, Tulare, and Taft in California [figures 90–92]. This rationalized planning addressed a typical function—the relief of day farmers and their families. Atypical, however, were the time frame of construction and life span of these facilities. Intended as emergency solutions to a temporary crisis, they were conceived as instant towns that would probably never mature and whose surreal character must have rivaled that of movie sets propped up in the middle of the desert.

Ironically, the social underpinning of the FSA venture, at least for the San Francisco office, generated an approach to architecture whose formal stance would be recognized internationally. Thus the cooperative farm of Chandler, for example, which Vernon DeMars and Burton Cairns planned and designed, was selected as one of the two examples of American modern architecture to illustrate Alfred Roth's Die Neue Architektur 1930–1940 .[21] Roth duly highlighted the design's response to climatic and functional constraints: the housing units were set at an angle to the road and at a right angle to the prevailing winds, so as to maximize their cooling capabilities. Adobe offered thermal advantages; its labor-intensive, self-help construction process provided work for the unemployed; and its traditional roots tied the buildings to the vernacular. The lower units were shaded by the first floor overhang, itself protected from direct sunlight by a protruding roof.

Roth also recorded the various landscape additions to this flat site, which before agricultural irrigation "was a cactus-covered desert." The kitchen-dining room extended outward, into the individual garden, under the shade of a poplar (albeit a strange choice for a shade tree). The garden was designed almost as if it belonged to a standard urban lot, in its elongated dimensions as well as in its features. The "sitting out place" was bounded by hedges, fragrant with herbs, and decorated with geranium, morning glory, and rockrose; the clothesline ruled over the lawn patch and a fruit tree marked the limits of the lot. Such mundane—yet elegant—arrangements revealed the importance of landscape as a common denominator within a wide spectrum of cultural origins. Everybody everywhere needed a tree, especially when "everywhere" was not home. Thus vegetation acted as an anchor to the land. It was both universal and traditional. Because of such features, Eckbo's efforts to create an indigenous

and formally innovative lexicon for the migrant camps were particularly noteworthy.

93

Shafter Camp. Tents on platforms with trellis extensions.

Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley, 1938. Farm Security Administration.

[The Dorothea Lange Collection, The Oakland Museum of California, The City of Oakland .]

A New Landscape Deal

Eckbo held one of the positions of landscape architect at the San Francisco FSA office (Regions IX and XI) from 1939 until 1942. Vernon DeMars became acting district architect, after the death of Burton Cairns; Herbert Hallsteen was district engineer and Nicholas Cirino, regional engineer. Their official goal was to design the physical framework for shelter, sanitation, education, and care for migrant workers across the western states. The majority of these camps were established in California, which, with its extensive mechanized agriculture and the vast influx of migrant laborers, required the most intensive relief efforts. Thus, the San Francisco office planned communities for Ceres, Gridley, Winters, Thornton, Westley, Firebaugh, Mineral King, Tulare, Shafter, Arvin, Brawley, Marysville, Yuba City, and Coachella. Other sites included Walla Walla, Granger, and Yakima in Washington; Yamhill in Oregon; Caldwell and Twin Falls in Idaho; Yuma, Glendale, Agua Fria, Chandler, Casa Grande, Eleven-Mile Corner, and Baxter in Arizona; Weslaco, Harlingen, Robstown, and Sinton in Texas. As a norm across the states, landscape design concentrated on providing

shade, preventing erosion and dust, and ultimately—to cite Eckbo—expanding and framing the architecture.[22]

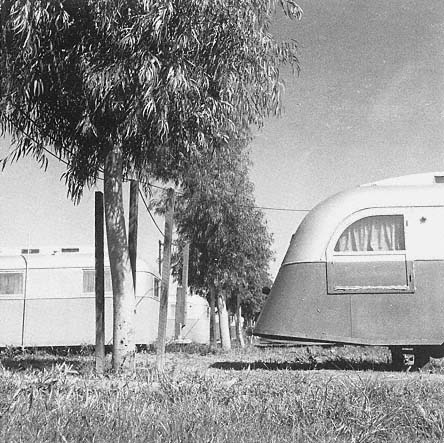

Economic, social, and climatic factors determined the planning of home, trailer, and tent communities for permanent, semi-permanent, and transient residents [figure 93]. The permanent section of the camps housed between one and three hundred occupants; the temporary areas needed to accommodate up to a thousand migrants, who lived in metal shelters—usually replacing the platform-tent units of the early camps—or trailers. The transients' area of the camp was arranged in a linear block pattern, hexagons, or double hexagons, to allow continuity of circulation within controlled borders. In contrast, the permanent residents lived in individual houses or multi-family housing that formed distinct neighborhoods. The site plans usually organized the homes in cul-de-sac pattern and staggered the one- or two-story apartment units to idealize orientation to sun and wind and to ensure privacy. The inhabitants of both houses and apartments maintained private subsistence plots. The park, sports, and recreational facilities complemented the community buildings, usually located close to the temporary residents' lodgings, where the demand for such amenities was greater [figure 94].[23]

94

Tulare Unit; central open space for the trailer camp. Site plan.

Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley, 1937–42. Farm Security Administration.

The assembly hall is at the right of plan with the utility building at left.

[Documents Collection ]

During his FSA years Eckbo experimented with what he termed the "assembly-line-technique" of modern site planning. Site planning integrated all aspects of design, a means to approach the expansive as well as the restrictive nature of landscape. He wrote that comprehensive study was needed to determine the best possible relationships among buildings, utilities, recreation facilities, planting, and open space. Thus, cohesive site planning, regardless of scale should be the "arrangement of environments for people." Its ultimate goal was to "produce the best possible physical pattern within which a group of people can develop a good social pattern."[24] Eckbo described gardens as forming spaces in which the structural elements of ground plane, enclosure, and canopy were interdependent and equally important.[25] But ultimately, the raison d'être of landscape design was to provide a setting for human activity, and the migrant camps were no exception.

The creation of diverse outdoor spaces defined with enclosures of varying heights and density—paired with amenities—fostered social exchange, during "free play" or games of baseball, in hanging laundry or dancing [figure 95]. The park, addressing the community building, served as an outdoor extension for the functions taking place inside—shaded and sheltered from the wind—and as the common green for the garden-less trailers surrounding it and for the colony as a whole. With the active practice of religion officially discouraged by the camp's "constitution," recreational activities would provide the arena for communal interaction.

As Eckbo observed in his article on design in the rural environment, the grouping of agricultural communities offered social and recreational advantages as well as those of cooperative economy: "whereas in the cities the need is for more free space (decentralization)," he wrote, "the rural need is for more intensive use of less space (concentration)."[26] The frontier model of the homesteader—in which the family stood as both the social and the recreational unit—needed revision. So did rural housing and rural recreation. The expansion of territory and scattering of population that characterized the industrialization of agriculture made social contact more essential than ever. Productivity may be a key element in the organization of a rural area, wrote Eckbo, but it still should rely on the understanding of the physical as well as cultural aspects of that area. Hence the need to grasp

95

Ceres Camp. Community recreation space. San Joaquin Valley, 1940. Farm Security Administration.

"Large tree patterns at the baroque scale of cheap rural land."

[Documents Collection ]

the importance of a well developed local road network, in addition to the interstate highway system, of grouped rural housing, and of organized recreation.

Rural recreation may be too novel a field to have established standards, Eckbo continued, but its facilities should foster group activities and competition, including concerts, dance, sports, and drama. But standards did exist, as evidenced by the three-volume Park and Recreation Structures published by the National Park Service in 1938. Formally, these campsites and facilities had little in common with Eckbo's take on the rural landscape—as they complemented forested natural beauties with rustic buildings and campfire circles. Furthermore, their aim also differed, in that the National Park tent and trailer campsites accommodated voluntary, and most likely urban, dwellers and not agricultural refugees. Despite their rather pastoral image, the National Parks exerted some form of control as "the tent camper seem[ed] to exercise (and to get away with!) an inversion of the right of eminent domain. He [held] any attempt to regulate his tenancy and conduct in the public interest to be ultra vires and inhibiting of his ruggedly individualistic prerogatives."[27] It was this very rugged individualism—generally associated with the frontier spirit of farmers—that appears to have warranted the strict arrangement, the supervising administration, and constitution of the FSA settlements. Instead of a layout of cabins, dining lodges, craft shops, and wash houses scattered amidst groves of trees by the Civilian Conservation Corps, the architecture and landscape architecture team of the San Francisco FSA office favored a highly hierarchical plan more akin to the Renaissance new town than to any "delightful informality" so scorned by Eckbo. The latter considered that "we may as well accept the fact that man's activities change and dominate the landscape," although adding, "it does not follow that they should spoil it."[28] Thus he would look toward the ordered patterns of agriculture as theaters for, and models of, design interventions.

Eckbo stated once again his sympathy for a formed landscape, arguing that the "romantic informality" of the countryside was a concept that had long needed overhauling; agricultural fields did not "'blend' with nature" but instead showed human organization of nature. Then,

he concluded, "whence . . . the theory that landscape and building design must go rustic in the rural areas."[29] To sustain his argument, he utilized the modernist architecture of the FSA camps as a possible model for rural housing. Part-time farm colonies that promoted sustainability, such as Chandler, had an edge over the camp dependent on, and an appendage to, the agricultural industry—a trend Carey McWilliams saw as encouraging, if only as a signpost on the road to reform. To McWilliams,

the real solution involves the substitution of collective agriculture for the present monopolistically owned and controlled system. . . . A partial solution will be achieved when subsistence homesteads have grown up about the migratory camps. . . . It is just possible that [the] latest recruits for the farm factories may be the last, and that out of their struggle for a decent life in California may issue a new type of agricultural economy for the West and for America .[30]

The FSA did attempt to stabilize migration patterns within various states. The highly specialized agricultural industry tended to employ a large seasonal labor force that rural communities could not absorb year-round. The relief administration thus experimented with variable-geometry or variable-demography settlements whose plans evolved from sports fields and vice versa. The camp of Woodville, located among the cotton, grapes, asparagus, and citrus fields of the lower San Joaquin Valley of California, was planned as the nucleus of a new small town. The aim was to retire the camp as the seasonal users were replaced with permanent residents—should additional employment arise. Located on a flat bare site, Woodville was praised by architectural critics for the quality of its planning as well as for the design of its community buildings [figure 96].[31] The arrangement balanced the temporary metal shelters with single and row houses that recalled those erected at Yuba City. Lavatory, laundry, and shower facilities served the migrant residents—constituting three-quarters of Woodville's population—while the co-op store, school, and community building joined camp and "town" areas. The tri-alar school and community building was a lesson in economy and flexibility: low prisms linked by exterior corridors opened the various classrooms directly to agricultural fields and orchards; with the assembly room

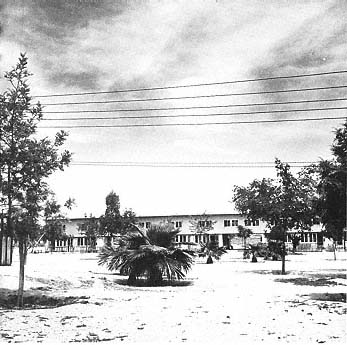

96

Woodville school and community center. Aerial perspective.

Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley, 1941. Farm Security Administration.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

doubling as the school gymnasium, the complex furnished "areas for child instruction, adult instruction, recreation, and social gatherings, adjustable to almost any use."[32]

Elizabeth Mock, curator of Architecture and Design at New York's Museum of Modern Art, assessed Woodville's "handsome buildings [as] the result of careful and economical design: FSA 's San Francisco office has shown that 'bureaucratic architecture' can also be distinguished."[33] The placement of the gatehouse beyond the center and homes area, "in control of the camp section only," so as "to remove any suggestion of a Government reservation," was perhaps an indicator of the social hierarchy within the settlement itself.[34] In their time-axis conception, such camps reflected similar patterns as those of immigration, for example, the recent arrivals pushing the lower strata upward.[35]

To complement such "touch[es] of European modern [architecture] in the western landscape," Eckbo sought an optimal structuring of outdoor spaces with planting patterns that were distinctly his own [figure 97].[36] At Weslaco, Texas, he designed a dozen variations for the park addressing the gatehouse and garage with modifications of the "grass-shrub-tree relationship."[37] All schemes, modular yet varied, bore a close resemblance to modern art, with formal manipulations of green elements—lines, arcs, and free forms [figures 98–99]. With outdoor rooms, suggestions of enclosure, and rhythmic punctuations of spaces, Eckbo followed the dictum of "blocking off portions so there is a succession of views and to set up movement and circulation."[38]

Throughout his landscapes, he formed space by arranging the elements of surfacing, enclosure, and "enrichment"—that is "pictures, 'compositions,' patterns [and] flower borders." With "enrichment" limited by economic or practical constraints, his equation relied on the possibilities offered by "sensitive and imaginative selection and arrangement of enclosure and surfacing elements." He saw this option as "equally satisfying with no more than the greatest enrichment of all—human life and activity."

Eckbo frequently asserted that open space should be considered the skeleton and controlling form of the site plan, rather than the by-

97

Weslaco Unit. Site plan. Texas, 1939. Farm Security Administration. Photostat.

Buildings in upper center frame the site of Eckbo's alternate park schemes, shown at left and opposite.

[Documents Collection ]

98

Weslaco Unit. Park for community building and gatehouse/garage.

Aerial perspective. Texas, 1939. Farm Security Administration. Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

99

Weslaco Unit. Park for gatehouse/garage. Four of twelve plan variations.

Texas, 1939. Farm Security Administration. Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

These studies indicate "the potential variety of grass-shrub-tree

relations which can be developed beyond the standard interpretation

of meadow." [ from Garrett Eckbo , Landscape for Living]

100

Mineral King Co-operative Ranch. Community park. Aerial perspective. Near Visalia, Tulare Basin,

San Joaquin Valley, 1939. Farm Security Administration. Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

101

Shafter Unit. Shelter/play structure. Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley, 1937–41.

Farm Security Administration. Note the combination trellis/bench/sandbox.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

product of the buildings arrangement and roadways.[39] As he entered the FSA office relatively late in the operation of the program, however, his major planning investigations were directed toward the design of the parks for permanent homes rather than the overall layout of camps [figure 100]. Built on federal land, the settlements were beyond the control or harassment of state and county agencies, and by private militias. Intended to protect—if not isolate—the residents from the environment and social tensions, the camp design attempted to create a climatic haven and a sense of place for the transients. To counter the aridity and heat of the California valleys, Texas, or Arizona, Eckbo used plantings as shelter and as the spatial structure for life and play [figure 101]. Tree canopies or trellises countered the sun or functioned as outdoor rooms complementing the tent, trailer, or housing units. The allées, screens, and clusters of vegetation defined specific spaces assigned to specific functions: roads, drying yards, common play areas, or individual vegetable gardens. Praising the designs the San Francisco office produced for the migrant workers, the architectural critic Talbot Hamlin hardly commented on the formal landscape improvements, but he remarked on the attention given to, and the necessity for, vegetation:

In all of this site planning the problem has been seen as a human and as an aesthetic problem as well as a problem in serving practical ends. Thus the most careful use has been made of existing trees, and where definite groves or stands of timber exist on the property these areas have been chosen wherever possible for the community buildings, the schools and the more permanent houses, so that the migrant driving in dusty after a day's work in blazing shadeless field or a long run over sunbeaten and windswept highways may find his relaxation in a place dappled with leaf shadows, embowered with trees and with the heartening feel of green and growing things around. Moreover, tree planting and a certain amount of modest landscaping has formed an essential part of all the communities .[40]

The site plan of the camp at Taft favored a centripetal arrangement in which the two-story units not only sought the best orientation but also formed a visual closure that served as a "sheltered oasis" [figure 102]. Heavy plantings of hardy species such as black locust, Siberian

102

Taft Defense Housing. Central open space. San Joaquin Valley,

1941. Farm Security Administration.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

103

Yuba City Unit. Aerial view. Sacramento Valley, 1937–39. Farm Security Administration.

Housing for permanent residents surrounds a grove of existing trees, in the foreground,

with the double hexagon of the migrant workers' trailer camp beyond.

[ from Architectural Forum]

elm, and coast beefwood withstood the extreme temperature range and dry climate of the San Joaquin Valley and structured the landscape scheme.[41] Highly tolerant of wind, drought, and poor soil conditions, these trees were also extremely fast-growing if irrigated. Such perfect subjects for soil conservation or land reclamation fought wind erosion by providing excellent windbreaks and shelter belts. In addition to creating express landscapes in deserts, Eckbo also relied on, or supplemented, vegetation present on the site. His interventions could be thus defined as either adaptations , the creation of oases within the harsh environment; insertions , when he complemented the landscape with a reinforcing vegetal structure; or appropriations , when he integrated entire groves of existing trees to his scheme [figures 103–4]. The planting plan of Winters, west of Sacramento, combined the latter two modes, as Eckbo laid out the Farm Labor Homes within apricot and walnut orchards and subverted their formal order with hedges, groves, and lines of hackberry, Chinese pistachio, and Chinese elm.

Eckbo described plantings not only as providing shade, greenery, color, and general amenity but also as the final refining element in the complete spatial design of the site. The landscape architect should collaborate with the architect and the engineer on site planning from the very beginning, wrote Eckbo, "if he is to be saved from the fate of being an exterior decorator for architecture. The keynote of the planting scheme should be the use of plants as space-organizing elements rather than as decoration."[42] Spines of trees offered protection from wind while enclosing spaces such as baseball fields or other play areas, reinforcing circulation patterns, and implying movement. Lines of shrubs also outlined outdoor rooms and multiplied view-points, thereby suggesting a continuation of space beyond the actual boundaries of the park.

For inspiration, Eckbo saw no better source than the rural landscape itself—the congruence of people and nature.

[With] innumerable definite three-dimensional space forms produced with both structural and natural materials: rectangular or polygonal fields cut from solid natural wildwoods; trees in rows or belts forming planes; the regularity of orchards; straight lines of

104

Yuma Unit; multi-family housing. Site and planting plan. Arizona, 1939. Farm Security Administration. Photostat.

[Documents Collection ]

untrimmed hedges and mixed hedgerows . . . ; free-standing clumps of trees forming natural pavilions; intersecting planes of these lines of trees and hedges and walls forming a fragmentary organization of space. It is seldom completely enclosed; always there is a suggestion of its continuity, something to follow, the stimulating impossibility of seeing all of the space at once .[43]

The landscape design of the Shafter camp appeared as an interpretation of the standard agricultural fields [figure 105–6].[44] Each of the twenty-nine permanent home lots was sufficiently large to raise subsistence crops, a majority of indigenous trees structured the two-acre park, and in the play areas, the "light frame trellis-and-screen structures [stood as] abstractions of typical practical agricultural crop structures." Despite the stringent budget, Eckbo accorded great attention to the spatial definition of house and circulation areas. Announcing the later vegetation codings of postwar projects such as Community Homes, he drew three site plans keyed accordingly to the height of trees and shrubs.

The camps were located strategically along the migratory routes followed by laborers, and within proximity of employment, which allowed Eckbo to take advantage of the extremely rich soil of the Californian agricultural valleys. And being of the opinion that "it has yet to be proven that long plant lists necessarily increase costs," he planted heavily and variedly.[45] He sought to create "large tree patterns at the baroque scale on cheap rural land," using eucalyptus, palm tree, and poplar as the backbone of the layout; oak, olive tree, and magnolia to offer shade; and almond and plum trees for color [figure 107].[46] Thus the geometries that looked rigidly systematic in plan were offset in reality by the variegation of trees and shrubs. This sampling of vegetation could be seen as reminiscent of the gardens Eckbo designed for Armstrong Nurseries—a panoramic range of species that softened the formality of the basic planting schemes [see figures 5–7].

Although simple in manner, Eckbo's schemes for the FSA camps displayed a sophisticated spatial layering—both vertical and horizontal—that recalled the formal variations of his theoretical Small Gardens in the City of 1937. In the landscapes of relief, the lessons of modern architecture were translated into planting designs where architec-

105

Shafter Unit; farm labor homes for permanent residents, with park. Site plan.

Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley, 1941. Farm Security Administration. Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

106

Shafter Unit; farm labor homes. Axonometric drawing. Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley,

1941. Farm Security Administration. Ink and pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

107

Woodville. The edge of row housing. Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley,

1941 Farm Security Administration.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

tonic screens were enlarged through vegetation. And these designs, destined for the lowest-income group, shared the same formal investigations as those of his avant-garde private gardens: a rare instance of aesthetics at the service of the expedient.

The shaping of camps into the hexagons of ideal town plans transcribed an inner political order—with its own constitution and higher committee. It revealed an order that strove for humanism against the outside world and its Red-bashing militias.[47] To promote communities that instigated social as well as economic rehabilitation, the architects of the New Deal attempted to create a miniature society whose naïveté in pursuing a democratic and collective spirit was matched only by its fondness for keeping rural folklore. If the first Roosevelt administration had been placed under the sign of planning, the great depression era coincided with the idealization of regionalism. In times of economic and social uncertainty, the longing for a more secure past and a sense of place typically holds the promise of a recoverable order. Perhaps the designs of FSA camps best expressed the tug-of-war between reform and relief, progress and tradition. Their manufacturers put forward the social ideals of modernism—both in landscape and architecture—as a tool for stabilizing the human drift across the land. Such projects acted not only as design exhibits but also as social beacons, as Paul Conkin concluded in Tomorrow a New World:

When a simple farmer, wide-eyed with wonder and expectancy . . . moved into a glittering new subsistence homesteads or resettlement community, he was entering a social show window. Willingly or unwillingly, knowingly or unknowingly, he was a human mannequin in a great exhibit, for the many architects of the New Deal communities, despite varying philosophies, were all striving to create, within the conducive environment of their planned villages, a new society, with altered values and new institutions .[48]

Eckbo's plantings evoked the order of, or sometimes borrowed from, the surrounding orchards; they also superimposed agrarian references and the indigenous with the forms of functionalism and exotic species. More often than not, however, Eckbo subverted the hermetic and controlling order of the camp. At Tulare, the hexagon-forming shelters addressed on one side the grid of an existing wal-

nut orchard and on the other the central open space with its utilities building and assembly hall [figure 108]. The park itself appeared to draw more from patterns of paintings by László Moholoy-Nagy or Kasimir Malevich than from any rural precedent. The dynamic diffractions of space – with overlapping allées and green hemicycles—was enhanced by varied plantings. With the diverse scales and textures of tree of heaven, silver dollar gum, olive, camphor, and bottle tree, the eye of the hexagon seemed independent from the order of the camp. Within the trailer-bound ideal shape, Eckbo inserted another set of rules, just as formal but based on another geometry. Modifying the vertical scale and the degree of usual transparency between the patterns, he completely abolished any remnant of a Cartesian reading. Ultimately his order—totally alien to both surroundings and migrants—became the norm for the central spaces of many of the camps scattered across the west.

Urban, highly educated, secular young men oversaw the daily lives of rural, mostly non-educated, and frequently fundamentalist laborers from Arkansas and Oklahoma.[49] Similarly, in spite of Eckbo's claims that "the country must be redesigned for country people —i.e., neither from the viewpoint of nor for the benefit of the urbanite," his parks for the FSA were, most likely, alien to anything country people might have experienced before.[50] He did succeed in creating spatial identity—albeit architecturally derived, art-referential, and mostly highbrow—within the agrarian landscape of the West. His plantings, which appeared originally so diminutive when photographed next to the ready-made architecture of the camps, have now matured, and form ghost images of their social endeavor throughout the California valleys.

In spite of the higher ideal pursued in the creation of migrant camps—that of a new pattern of community life removed from an individualistic and materialistic society—the quantitative production of the FSA was deemed by many to be at best a stopgap solution. Not only did the sheer volume of exploited farm laborers living in squalor overwhelm the capabilities of the relief agency, but the assistance to migrants remained superficial rather than structural. The government-run camps functioned as a subsidy for farmers that relieved them of responsibility to provide housing or minimal wages.[51]

108

Tulare Unit. Site and planting plan, detail (12 December 1941). Tulare Basin, San Joaquin Valley. Farm Security

Administration. Blueprint. The shelters form a hexagon around the park; an existing walnut orchard lies between

the migrant section and the permanent residents' homes.

[Documents Collection ]

The results of such efforts, whose limited scope was perpetually threatened by agribusiness lobbies, are sadly summed up in today's migrant settlements, still inhabited by agricultural laborers—though of a different ethnicity [see plate II].[52] As Cletus Daniels concluded:

Farmworkers in California were poor, uprooted, and powerless people long before Franklin Roosevelt's voice crackled over the radio imploring middle America to have courage in the face of depression and promising a new order of prosperity and economic justice in the days and years ahead. And they were no less poor, uprooted, and powerless after the reformist enthusiasm of the New Deal had waned and the attention of the nation had shifted from domestic to foreign affairs .[53]

Emergency Landscapes

Between July 1940 and July 1943 at least three million workers had moved to sustain the ship, airplane, and munitions industries; with their families, the displaced masses totaled about seven million people.[54] They urgently required living accommodations. Name-brand architects contributing to the landscape of defense housing included Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer, Eliel and Eero Saarinen, Buckminster Fuller, and more locally, William Wurster.[55] California's population increase made "the once famous Grapes of Wrath problem look like a picnic," stated the planning and housing expert Catherine Bauer.[56] Recognized for its efficient provision of emergency housing, the FSA had shifted its focus from migrant laborers' assistance to defense housing by 1941 [figure 109]. Eckbo served as landscape consultant for about fifty of these war housing projects. The socially and architecturally radical—and somewhat quixotic—efforts of the FSA era were definitely over as the government turned on its own. In 1942, before leaving the relief administration, Eckbo worked on developing camps for "Japanese evacuees" in the Owens Valley. His projects include the landscape plan for the staff housing section of Manzanar, a relocation unit for Japanese Americans. The camps of Marysville and Tulare originally destined for workers from the Dust Bowl, now served as temporary internment quarters.[57] Eckbo had joined the FSA to formulate a sheltering landscape for the displaced and landless; now

109

Defense housing trailer park. San Miguel, 1942. Farm Security Administration.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

—however tragically—the relocation centers served as a mean of pure control, and instead of offering a sense of place reprieved from the outside world, they brought only a sense of isolation.

Eckbo had applied the lessons of high art, first advanced in the Contempoville project, to the basic functionalism of the FSA camps. In a similar way, he would learn from his experience with defense housing and trailer camps to establish a pattern for postwar suburban developments. As he would later write in Landscape for Living:

The general theory is the grouping of the units in articulated cellular patterns in which the cells achieve special identity by virtue of the strong formal relations established within them. The total grouping achieves a spatial organization of the site with considerable movement and quality. Tree patterns and building colors can of course expedite this identifying articulation a great deal .[58]

Eckbo's contribution to FSA California war housing included the landscape plan for 72 units at Taft, designed by Vernon DeMars, and that for 3,000 single Navy workers and 200 families at Vallejo, with Theodore Bernardi and Vernon DeMars [figure 110]. Like Thomas Church's vegetal solutions for emergency landscapes, Eckbo's scheme for Vallejo attempted to provide neighborhood identity while relieving the rigidity of the matter-of-fact site plan. He relied on windbreak allées of Lombardy poplars and weeping willows to edge the various clusters of cabins, dormitories, restaurant, and administration buildings. He interspersed this formal order with specimen plantings of Japanese privet, sycamore, and Pittosporum nigricans , much as he had keyed the various areas of migrant camps with vegetation. The same ideal underlay FSA projects and war housing as "every technician involved in developing environments for people is responsible not just for providing shelter, but also for developing their fundamental potential dignity" [figure 111].[59]

Eckbo argued for planning defense housing without "the sacrifice of essential space to the twin bogeymen of cost and mechanical gadgetry, [nor] the vicious practise of developing minimum standards based on income strata, rather than optimum standards based on bio-ethnic needs," which he foresaw as "too apt to produce the slums of tomorrow."[60] In this deprecation of the Housing Authority's stan-

110

Defense housing "duration dormitories" and cabins for Navy yard workers. Site plan. Vallejo, 1942.

Farm Security Administration. Tenant activities building seen in the upper segment of the site plan

was designed by Bernardi, De Mars, Wickenden, Langhorst, and Funk.

[Documents Collection ]

111

Defense housing dormitories. Sausalito, 1946.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

dards, he echoed Catherine Bauer's assertion that public housing and even more so, war housing, allotted too little space to both interiors and exteriors. This was a stance that Eckbo shared again, when he deemed that after the sacrifices of the war effort, Americans deserved, not minimum, but optimum standards in housing.

A New Landscape for Living

Eckbo later recalled that no other project had given him as much satisfaction as designing landscapes for the migrant camps, resulting from the "combination of large open site without intensive demands beyond the already existing natural character and the social function." "As human density on the land increases," he continued, "demands for specific functions become more intensive. Trees, to survive at all, must be placed within (and enhancing) those functional patterns, rather than exploring those freer conceptions that [he] had dreamed of."[61] In spite of such reservations, functional constraints occasionally served design by reinforcing, and offering a foil to, Eckbo's space-defining plantings and "freer conceptions." In this regard, housing provided an essential driving force for his formal investigations.

In his postwar Flexible Co-op project, Eckbo conceived the house and garden as a whole. Individual privacy, family living, service elements, and public approach were integrated as indoor-outdoor sequences [see figure 83]. Privacy and views resulted from the planning of both the proximate and neighborhood contexts of the house. The optimum postwar standard of living required the planning of community facilities to parallel private amenities, much like the community building, parks, and public recreational facilities that complemented the homes and gardens of the FSA camps and the rural areas around them. In the Flexible Co-op project, group and child-care centers, neighborhood eating centers, laundry and shopping facilities reduced household drudgery, freeing women for more satisfying activities.[62]

In 1945 Eckbo collaborated on the site plan for the housing development of Ladera with Robert Royston and Nicholas Cirino—who had held the position of engineer for the FSA San Francisco office—and architects Joseph Allen Stein and John Funk, with whom he then shared an office [figure 112]. The founders of the

Peninsula Housing Association—who, like many postwar home builders, were disenchanted with typical suburban developments—had turned toward cooperative organization and the promise it held for an ideal democratic community.[63] The project distributed 400 single-family houses on a hilly 256-acre tract near Palo Alto, south of San Francisco. The plan called for an elementary school, kindergarten and playgrounds, gas station, guest house, and recreational, community, and commercial facilities. The shopping center was situated at the edge of the property in order to also serve surrounding developments, just as the community buildings of the migrant camps had served residents and neighboring farmers alike.

Balancing privacy and public amenities, the planning of Ladera echoed the recommendations of the Flexible Co-op project that demanded facilities for children, recreation, and shopping facilities. Broadly articulated by two through streets and a large wooded area, Ladera's overall plan laid out, along culs-de-sac, single lots that ranged between a quarter acre to two-and-a-half acres. In most instances, footpaths were segregated from vehicular traffic and residents could walk to park areas from almost anywhere in the subdivision without having to cross a through street. In addition to the existing clusters of live oaks, tree plantings reinforced neighborhood identity without obstructing views. The intention of Ladera's sponsor had been to create a rural community, where people could "enjoy the advantages of country living, but without the high costs, isolation, and inconveniences we would face if we each tried to go it alone."[64] Their ideals validated Eckbo's arguments for the planning of cooperative farms during his tenure in the FSA .

Stein and Funk designed a dozen unit plans. The layouts ranged from compact square units complemented by paved surface and a small garden, to pin-wheel plans that extended their walls into the landscape to form green rooms, to bipolar plans in which the outdoor space penetrated the house to articulate the separation between sleeping and living areas. Overall, large expanses of glass increased the spatial perception of the houses from within and erased the division with the garden; Eckbo virtually mirrored the interior functions with complementary outdoor rooms—whether paved or carpeted with lawn—defined by hedges and screens. Ironically, the public play-

112

Ladera Housing Co-operative. Site plan. Palo Alto, 1946–49. Joseph Allen Stein, John Funk,

architects; Nicholas Cirino, engineer; Eckbo, Royston and Williams, landscape architects.

Color pencil on diazo print.

[Documents Collection ]

grounds were bounded by rectangular or circular perimeters like distant memories of the FSA parks constricted by the ideal geometries of the site plan [figure 113].

113

Ladera Housing Co-operative.

Playground for children ages

5–11. Plan and axonometric

drawing. Palo Alto, 1947.

[ from Garrett Eckbo ,

Landscape for Living]

Only a minimal part of the proposed overall layout and architecture of Ladera was ever carried out, as the Federal Housing Authority turned down the request for a construction loan—perhaps because of the group's racial integration. By 1949, with 35 houses built using individual financing—one house and lot at a time—the cooperative association was dissolved and the site sold. The planning of Ladera was then revised and partially redeveloped by Eichler Homes with houses designed by architects Quincy Jones and Frederick Emmons.[65]

Before Ladera's construction—or rather its transformation—had materialized, Eckbo moved to Los Angeles to nominally establish, in 1946, the southern branch of Eckbo, Royston and Williams. There, he collaborated with Gregory Ain on several housing projects, of which Community Homes in Reseda remains the most ambitious [figure 114]. In its social endeavor, democratic process, integration of architecture, private garden, and public landscape, its hierarchical favoring of pedestrian circulation and greenery over infrastructure and automobile traffic it offered a postwar southern California suburban equivalent to European, and in particular Swedish, cooperatives. As a writer for Arts and Architecture stated, cooperatives "are successful only when the need is real and close to the members' personal security. They atrophy or are vegetative when interest is passive and intellectual."[66] The project's architect was Gregory Ain, in collaboration with Joseph Johnson and Alfred Day. The scheme grouped 280 single-family homes on 100 acres of flat land in the San Fernando Valley. The overall plan—by Simon Eisner—formed a large L, articulated by sixteen acres of open spaces that dissected each leg.

The two expansive "strip parks," and uniformly distributed "finger parks," offered proximate recreational spaces for people of all ages throughout the grid of houses and gardens [figure 115]. Recalling FSA experiments in vegetal structure, Eckbo devised a master tree plan with a "backbone" pattern of vertical formal accents—fan palm, Canary Island pine, Lombardy poplar, incense cedar, Italian cypress, and a large variety of eucalypts—as the ordering structure for a mix of 79 types of trees. The rigor of this vegetal skeleton was offset by

114

Community Homes. Site plan. Reseda, San Fernando Valley, 1946–49. Garrett Eckbo, landscape architect;

Gregory Ain with Joseph Johnson and Alfred Day, architects; Simon Eisner, planner. Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

115

Community Homes, Strip Park. Plan study. Reseda,

San Fernando Valley, circa 1948. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

116

Community Homes. Tree diagram. Reseda, San Fernando Valley, circa 1948.

Pencil on tracing paper. High species included fan palm and Canary Island pine;

medium species, Italian stone pine, southern magnolia, and camphor;

and low, purple-leaf plum and photinia.

[Documents Collection ]

117

Community Homes. Tree diagram. Reseda, San Fernando Valley, circa 1948. Pencil

on tracing paper. Here, Eckbo examines spatial patterns in relation to tree shape and texture.

[Documents Collection ]

the broader silhouettes of the "grove trees": London plane, Chinese elm, fruitless mulberry, cut-leaf silver maple, and weeping willow, and irregular plantings of shade trees, flowering trees, and fruit trees.[67] The tree plan was approved by the constituents via a thoroughly democratic process, Eckbo recalled, and like the landscape of the migrant camps, it drew from the "still rural character of much of the valley around it."[68] Tree patterns aimed to express neighborhood identity using spatial, structural, and textural qualities of the plantings. He alternated the heights of trees—low, high, and medium—and their shapes—columnar, "Christmas," plume, ball, and spreading. Transparency and the sense of enclosure varied within the architectural and planning matrix: a different order—that of vegetation—underlined yet subverted the uniform grid of houses.

Eckbo's diagrams included a significant amount of information, as they indicated height, density, shape, and whether the species was evergreen or deciduous [figures 116–17]. This graphically sophisticated encoding reveals upon study a wealth of spatial variations. Tall evergreen "plumes" essentially ran east-west, to provide shade against the southern exposure as well as a formal connection to the main recreation spine of the development—itself signaled by rows of palm trees. Eckbo suggested alternate scales within the grid of houses. By varying the height and opacity of vegetal enclosures he modified the planned order: blocks were either expanded—their unit boundaries minimized—or on the contrary, vegetation articulated the individuality of each cell within the suburban pattern.

Ain and Eckbo's integrated house and garden plans shared the clarity and simplicity of contemporary Ladera's spatial organization. As a juror, Ain had described the 1943 competition for "Designs for Postwar Living"—sponsored by Arts and Architecture —as a "Cooperative symposium." He saw the entries as reflecting what the "average citizen" required, indicating the "acceptance of a trend toward simplicity and directness . . . and the need to consider the relation of one dwelling to another. [The projects also affirmed] the need for 'livability' beyond the satisfaction of the purely mechanical functions of a house."[69] Such a stance would ultimately express his own approach to postwar housing, planning units in relation to one another and the community, with gardens that answered the interiors and

a simplicity of execution that afforded maximum space with minimum means.

For Community Homes, Ain designed four typical house plans, whose variable configurations met the differing needs of their residents [figure 118]. Options ranged from compact two-bedroom, one-bathroom units, to slightly less compact three-bedroom, two-bathroom homes. When the dimensions of the kitchen precluded a breakfast nook, an opening between the cooking and dining-living areas allowed "the housewife to participate in social activities in the living room."[70] Sliding partitions permitted the conversion of two rooms into one. Overhangs, screens, and hedges extended the architecture into the garden.

Transparency—like the multiplication of interior rooms—made the outdoor space read as a paved mirror image of the living room, furnished with redwood rounds, specimen shrubs, and arbor [figure 119]. Similarly, Eckbo proposed alternative gardens according to needs and maintenance requirements, although none offered the vegetable plots of his earlier Flexible Co-op scheme. Possibilities ranged from a garden for the "active home farmer dirt gardener" to that for the "lazy one who just wants fun in the yard;" all fencing between lots balanced neighborliness with privacy.[71] To achieve a continuous landscape frontage along the street, he kept the vegetation open—with trees springing from planes of lawn or ground cover—limiting hedges or screens to the sheltering of the living spaces. In the backyard, on the other hand, Eckbo favored privacy and structured spaces, with arbors, flower beds, grape stakings, and "tall untrimmed hedges." This seclusion was not complete, however, as interruptions in hedges allowed a glimpse of, and passage to, the semi-public inner block "finger park." By separating cars from pedestrians, and interspersing greenbelt parks, pocket recreation spaces, and private gardens, Community Homes promised an alternative to more common suburban development [figure 120]. It would have been one of the most progressive experiments in communal home building, arguably unmatched in the United States since Radburn and Baldwin Hills Village.

During the postwar building boom, cooperative communities had become rather common endeavors—promoted in shelter magazines

118

Community Homes. House and garden plan

(type "B"). Reseda, San Fernando Valley,

1946–49. Gregory Ain with Joseph Johnson

and Alfred Day, architects; Garrett Eckbo,

landscape architect. The gap in the backyard

hedge allows passage to the "finger park."

[ from Garrett Eckbo , Landscape for Living]

119

Community Homes. House and garden plan.

Reseda, San Fernando Valley, 1946–49.

Gregory Ain with Joseph Johnson and Alfred Day,

architects; Garrett Eckbo, landscape architect.

[ from Garrett Eckbo , Landscape for Living]

"Our house is small but if we handle it properly

we can extend our living space right to the

property lines." [ from Richard Neutra ,

Mystery and Realities of the Site, in a

review of the book by Garrett Eckbo, 1951 ]

120

Community Homes. Aerial perspective. Reseda, San Fernando Valley, 1946–49. Garrett Eckbo, landscape architect;

Gregory Ain with Joseph Johnson and Alfred Day, architects; Simon Eisner, planner.

[ from Garrett Eckbo , Landscape for Living]

such as House and Garden —more typically resorting to conventional architectural expressions.[72] Those very tenets of defense housing Eckbo had questioned seemed to direct Federal Housing Authority programs, which subsidized home construction in terms of their sale or resale value. Innovative design could thus prove a hindrance, as no "theories or 'schools of thought' . . . should be allowed to interfere with this clear expression of the law-making body."[73] Financing was almost a formality for veterans without "too unconventional ideas about architecture, nonsegregation or restrictive covenants," as Vernon DeMars pointed out.[74]

Of course, Community Homes hardly fit the bill. The lengthy process—three or four years spent organizing the group, purchasing the land, meeting with various planning departments, and revising floor plans—came to a grinding halt with the Federal Housing Authority's decree that the inclusion of minorities jeopardized good business practice.[75] DeMars noted:

Co-operatives have traditionally insisted on nondiscrimination as to race, creed, and color, a rather academic consideration in England or Scandinavia, and one presenting no difficulty in running a consumer's grocery store in the United States. Housing is something else again, and co-operatives should abandon not idealism but naïveté. Better housing is, in itself, a crusade—so is the co-operative way .[76]

The subscribers of Community Homes believed that better housing should not abandon idealism: veterans of all races had fought in the war. Bureaucracy prevailed, however, and the project was terminated through Regulation X, which prevented the Federal Housing Authority from insuring loans for racially mixed developments.

Community Landscapes

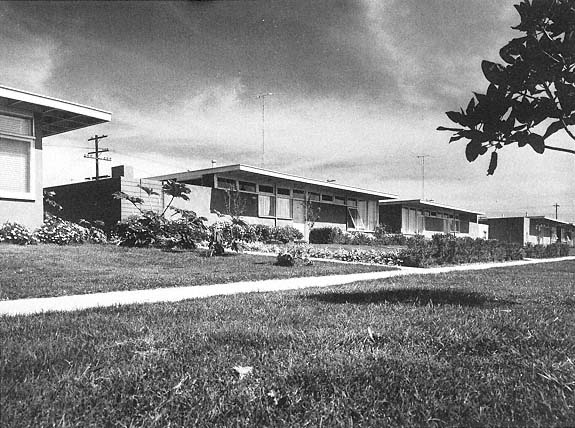

In 1946–47 Ain and Eckbo also designed Park Planned Homes, only a part of which was realized [figure 121]. The subdivision was originally planned to span four square blocks of Altadena, but of its projected sixty units only twenty-eight were ever built—along a single street. To increase economy, Ain resorted to semi-prefabrication. Savings were ultimately minimal, however, with building crews demanding higher wages for less labor. These practices confirmed Ain's prejudice

121

Park Planned Homes. Site plan. Altadena, 1946–47.

Gregory Ain, architect.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

122

Park Planned Homes. Altadena, 1947.

Gregory Ain, architect.

[Julius Shulman ]

against standardization, which most contemporary architects seemed to consider an aim in itself, and an "incidental means to mass production of good dwellings."[77]

The 1,600 square-foot houses, oriented east-west, were placed on quarter-acre lots stepping down the incline of Highview Avenue [figure 122]. Of reasonable size, with three bedrooms and two baths, a patio-garden in the back and a play area/service yard in the front, large expanses of glazing and a clerestory for light and ventilation, the buildings offered openness and transparency without undermining privacy. The garages—paired and sharing a driveway—sheltered the service yard and children's play area from the street. Although both the site and floor plans show Eckbo's varied designs for individual gardens, the streetscape received his closest attention.

With the houses and garages set back from traffic, ninety-six-foot long planting strips provided a green transition between street and house. These islands of brilliantly colored flower beds were intended to combine with the varyingly painted street facades to relieve monotony. The planting schemes for Community Homes used trees to form linear spines or allées through the residential neighborhood and even to subvert its order. For a distinct identity, Eckbo usually keyed species to a block, a street, or at least a cluster of houses. The vegetation of Park Planned Homes was far more variegated within a smaller range [figure 123]. Here, he alternated heights and textures with each pair of garages and, coupled with the staggered driveways across the street, achieved a shifted allée of fragments. From the quincunxed planting strips sprang Lombardy poplar, olive, dwarf eucalyptus, and Mexican palm, to name only a few elements of the complex vegetal palette. Nearer the front door, the plantings became more regular—with Chinese pistachio marking the entrance to houses—culminating in the green frame of the hedges that outlined the rear gardens. With this variety of street trees, Eckbo established a play between street landscape and service yard, as private canopies emerged from behind enclosures and merged with the public landscape, making the latter part of the private realm while magnifying the streetscape of Highview Avenue.

Today, the image of Park Planned Homes is hardly that of an idyllic community, with collections of cars in various states of disrepair clut-

123

Park Planned Homes. Planting plan (27 February 1947). Altadena.

Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

tering some driveways. The elegant balance of solid and voids has been distorted over the years, as additions were built and courtyards filled. A glance at the model of the original scheme affirms the idiosyncratic entente between Ain and Eckbo, whose interest in the social planning of housing communities outweighed that of designing luxurious individual houses and their gardens.

The two designers would renew their collaboration in Mar Vista, a planned development east of Venice [figure 124]. Completed in 1948—if only partially, with only 52 of the intended 100 houses constructed—Mar Vista probably remains the most compelling evidence of a model joint venture among architect, landscape architect, and developer that would provide an alternative to the sterile productions of the "banker-builder-realtor trinity."[78]Arts and Architecture reported that to the Advanced Development Company, the project's developer, a house was not a mere commodity as it is for the typical builder—that is, an object to be bought and sold. Instead, it exemplified the "broader and more human definition of the word commodity ," that is to be convenient and provide amenity and accommodation.[79]

Modernique Homes (as the project was advertised)—of roughly 1,050 square feet on 75 x 104-foot lots—featured a basic unit type, with eight possible relations of house to garage and house to street [figure 125].[80] Intended to appeal to the average veteran, the house was situated on an average lot and intended to answer average needs. Modern planning fostered "full use of necessarily limited area; removal of living room from the main line of traffic through the house; direct connection of the living room with garden area away form the street; ease of maintenance, etc."[81] Sliding partitions provided flexibility within and increased a sense of openness and functionality. This description—equally applicable to the houses of Park Planned Homes and even Ladera—fit Ain's overall approach to low-cost housing, which he had already announced while judging the 1943 design competition for postwar living:

A few plans, compact and well-studied, were eliminated early . . . as architectural clichés. They were well organized, had good interrelation of rooms and gardens, and adaptability to restricted sites, and especially showed intelligent regard for the "Amenities of Living" (a cliché incidentally). They were reminiscent of some -

124

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Aerial perspective. Los Angeles, 1948. Gregory Ain, architect.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

125

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Los Angeles, circa 1949. Gregory Ain, architect.

Meier Street around time of completion.

[Julius Shulman ]

thing that had already been done, but something that could well become a respected tradition. But it must not be forgotten that some clichés are so apt and forceful that they eventually became valuable additions to a vocabulary .[82]

Similarly, Eckbo would refine his own clichés, or "valuable additions to a vocabulary" of landscape design and planning: neighborhood identity, relation of the individual to the group, manipulation of ground plane, spatial definition of overhead, and enclosure. He fully understood Ain's modest yet persevering attitude, later writing: "In all . . . Ain projects, the houses had a repetitive clarity with subtle variations. They challenged me to exploit variations in garden design for smaller spaces, and variations in street front treatment within overall unity" [figure 126].[83] Mar Vista was no exception, as Eckbo blurred once again the division between public and private domains, treating the buffer gardens as an expansion of the common green, and pulling the sidewalk away from traffic. He lined the streets with wide lawn strips and allées of magnolia on Meier, melaleuca on Moore, and ficus along one side of Beethoven. The character of each of these blocks varied greatly [figure 127]. With the allée of magnolia—a slow-growing species—the space is read as continuous from house to house, with the street causing a mere interruption to the texture of the predominantly linear green expanse. Dominating the houses on Moore Street, on the other hand, the vigorous melaleuca form a green nave resting on white trunks that divides the space as pedestrian-car-pedestrian [figure 128]. Finally, Beethoven Street stands as a case study of "before and after" or "if you don't do this, you'll get that" [see plate III]. Although ficus and magnolia are quite similar in their bearing and appropriateness as street trees, Meier and Beethoven streets lie worlds apart. Size, of course, is one issue, as the ficus firmly anchor the edge of the Modernique development. Ain's houses and Eckbo's plantings line only one side of Beethoven Street, with the other half displaying in full sun the hodgepodge of styles and yards that characterize most unplanned developments. Thus Mar Vista clearly demonstrated the superiority of intelligent planning as a vehicle for neighborhood amenity and identity.

The urban or suburban context dominated the equation among architecture, city, and landscape in the designs for Community Homes, Park Planned Homes, and Mar Vista. In contrast, landscape

126

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Los Angeles, 1948.

Gregory Ain, architect. Moore Street seen through an

entrance atrium.

[Julius Shulman ]

127

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Los Angeles,

1948. Gregory Ain, architect. Meier Street, showing existing

mature eucalyptus as well as newly planted magnolia.

[Documents Collection ]

128

Mar Vista Housing (Modernique Homes). Los Angeles, 1948.

Gregory Ain, architect. Moore Street today.

[Marc Treib, 1996 ]

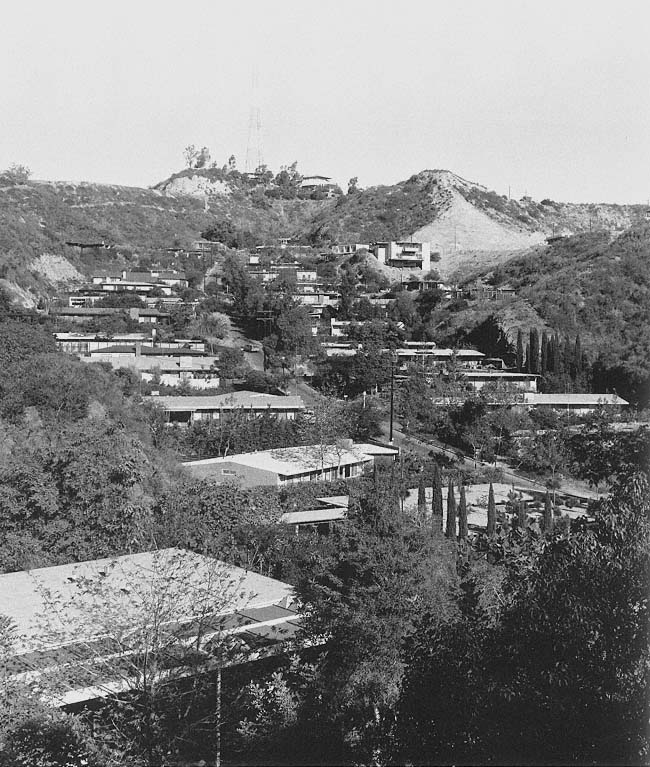

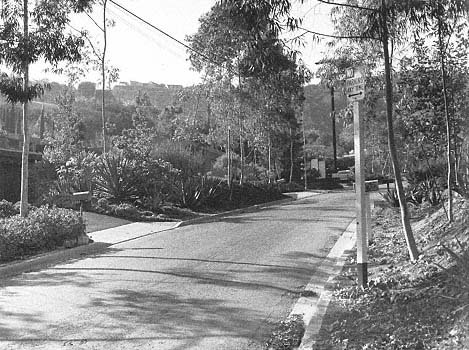

weighed the balance in the site planning of Crestwood Hills and Wonderland Park, as if on such hilly terrain, the human hand, or its design, was to bow against nature.