The Pool in the Garden

In 1941 Margaret Olthof Goldsmith advised her presumably affluent clients that "When you think of the money spent in renting a summer cottage on a distant lake or seaside, and in getting there year after year, you will find a swimming pool a good investment. . . . No one who has a good swimming pool will deny that it yields a return that justifies its cost." Despite this sheaf of purported benefits, she admitted that "it is costly, just as an automobile is costly." The incidence of swimming pool construction in southern California continued to mount after the war, while the price of pools continued to drop. Even in far-off New York State, presumably the setting for John Cheever's "The Swimmer," the pool had become such a ubiquitous element of the domestic landscape that the story's protagonist could consider swimming across a sequence of suburban backyards: "He seemed to see, with a cartographer's eye, that string of swimming pools, that quasi-subterranean stream that curved across the county."[87] Given that Los Angeles is essentially an irrigated desert, the swimming pool became an object of intense desire for those with the means to build them [see plate IX].

Its dimensions often made a pool the garden's most prominent feature, and in many of the Eckbo designs it became the point of departure for the spatial composition [figures 54, 55]. Given its aristocratic birth in the estates of the wealthy, the pool was normally set off from the principal part of the garden and screened from view. But the restricted lot sizes of Californian suburban development precluded such a privileged distinction, and the landscape architect was forced to integrate the pool into the garden as a central feature. For Thomas Church the pool served a multitude of purposes both aesthetic and useful:

It can remain a simple reflection pool in the garden, in which you occasionally take a dip, or become a complete entertainment center where you have as many fascinations for children and guests as you can dream up. It may have a cabana with shade and lemonade, or maybe it has a bar. If there are youngsters around, it might have a soda fountain and a sandwich counter. If your guests stay for the weekend, it can double as a guest house.[88]

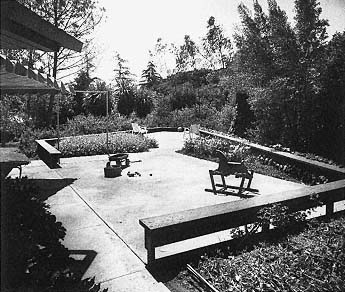

53

Chappell garden. Bel Air, mid- 1950s. Although the redwood

bench demarcated the limit of the patio, planting intruded,

softening the sense of boundary.

[Maynard Parker, courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

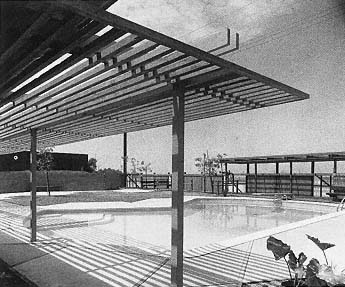

54

Pool and pergolas, Bellehurst Estates. Los Angeles, late 1950s.

[Julius Shulman ]

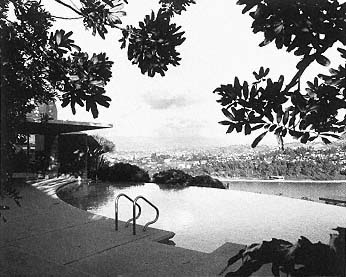

55

Reiner garden. Los Angeles, late 1956. John Lautner,

architect. The waterline extends to the very edge of the pool,

visually merging with the Silver Lake reservoir beyond.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

Thomas Church's Donnell garden of 1948 immortalized the kidney as the archetypical Californian pool shape.[89] With its command of a hilltop in Sonoma County, its sweeping view toward San Francisco Bay, and the contemporary flavor of its swimming pool, the design captured the imagination of readers and designers, nationally and internationally, as the epitome of a modern setting for outdoor living [figure 56]. But if the pool's shape could embody absolute contemporaneity in some Church designs, it could also play a more refined role, almost in the manner of a classical Italian garden. Church's Henderson garden in Hillsborough from 1958, for example, used the pool to establish the axis of the central area, linking the house with the landscape beyond [figure 57].

Eckbo, in contrast, found in water a more active catalyst for reading the space, using to advantage both the pool's exotic shape and its relation to other elements of the garden composition [figures 58-60; see plates X, XI, XVI]. Writing to the professional, he suggested the place of the liquid in the garden design:

The landscape architect must think of water, not only as a provider of coolness and repose or motion or life, or even as a translucent veil which intensifies the color and texture of any material across which it is drawn, but also (because one does not step into a pool without careful preparation) as a positive space-organizing element which controls physical movement, knocking a hole in the site, but does not block the movement of the eye .[90]

Thus water—most notably as swimming pools—came to prominence in Eckbo's postwar garden designs for the arid Southland.

Pool form varied with the shape of the site, orientation, location, and its compositional function within the garden. Put simply, "the garden must shape the pool, rather than being forced to conform to it." One pool, for example, anchored a garden design intended to expand "the outlook direction derived from the house form."[91] To accommodate a paraplegic client, for whom water offered pleasure as well as exercise, a pool was bent and gently sloped for wheelchair access [figure 61; see plate XI]. In contrast, to maximize the dramatic potential of the pool for a bathing suit designer, the Cole garden in Beverly Hills

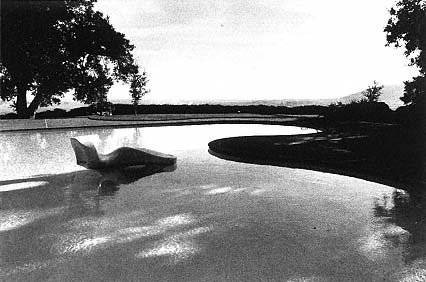

56

Thomas Church. Donnell garden. Pool with sculpture

by Adaline Kent. Sonoma County, 1948.

[Marc Treib ]

57

Thomas Church. Henderson garden. Hillsborough, 1958.

William Wurster, architect.

[Marc Treib ]

58

Hartman garden. Axonometric view of pool and pool house. Beverly Hills, 1946.

Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

59

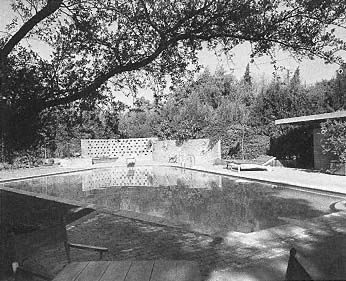

Hartman garden. Beverly Hills, 1946.

[Julius Shulman ]

60

Hartman garden. Trellis and textured

wooden screen walls. Beverly Hills, 1946.

[Julius Shulman ]

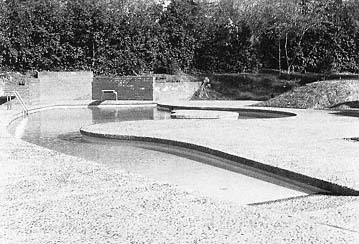

61

Cranston garden. Los Angeles, 1950s.

[Garrett Eckbo ]

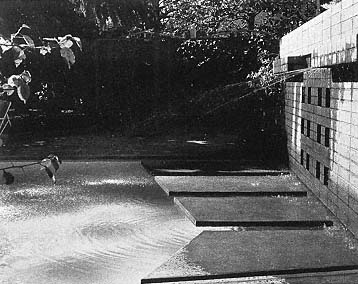

62

Cole garden. Beverly Hills, early 1950s. The masonry wall was

supported on a beam spanning the pool, allowing swimmers to

emerge from beneath the cantilevered concrete pads.

[Evans Slater, courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

63

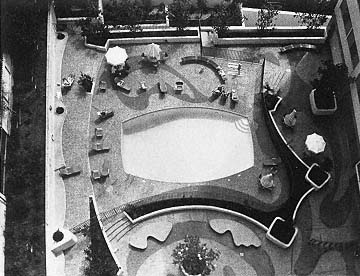

Churchill Apartments. Patio and pool. Los Angeles, mid-1950s.

William Lescaze, architect.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

concealed a rear pool area from view. Models, clad in the latest aquatic fashion, would clandestinely enter and emerge into the main pool from beneath the masonry screen wall [figure 62; see plate X]. Pool shapes ranged from simple rectangles to angular boomerangs, stiff amoebas, and folded kidneys [figure 63]. The formal/spatial idiom might be termed cubo-biomorphic, or simply cubo-bio, an astute mixture of cubistic (or suprematist) forms with the curvilinear shapes that recalled the work of Joan Miró, Jean Arp, or Isamu Noguchi—artists with whom Eckbo was well acquainted.[92]

Of the hundreds of gardens designed by Eckbo during the period from 1946 to 1960, the Goldstone garden in Beverly Hills serves as a typical, if extreme, example. The sweeping arched wall of the garden, completed in 1948, confronted the living spaces of the existing house [figures 64, 65]. The forms of the garden are in fact alien to both their site and the style of the architecture; instead, the landscape is a respite from banality, a more perfect world of contemporary form, shape, materials—a sculpture encompassing living outdoors [figures 66, 67]. In plan an active and complicated geometry played angled walls against the swimming pool of composite rectangular/circular profile. These elements were unified by the sweeping masonry and glass bottle wall that backdropped the entire composition. Around 1950 Eckbo became more interested in shade, shadow, pattern, and texture in the garden, as much by architectonic means as by vegetation.[93] The wall reveals those interests. Rather than a conscious decision to use built form instead of plants, the shift seems to have broadened the means for making the garden.