The Move South

Eckbo held fond memories of the Southland from his short tenure with Armstrong Nurseries in the mid-1930s, and saw the vast sea of opportunities for landscape architects there. In contrast to the more restrained design arena of northern California, the Los Angeles area had been open to the aesthetic avant-garde since the 1920s. For Eckbo: "There was a sense of drive, action, dynamism that I had never felt in the north." This innovative climate, perhaps spurred on by the film industry, had fostered unbridled experiments in space and form, from the early houses of architects including Frank Lloyd Wright, R. M. Schindler, and Richard Neutra, to the Second Generation represented by John Lautner, Gregory Ain, Craig Ellwood, and Raphael Soriano, among others.[78] The influx of émigrés beginning in the 1930s further stimulated developments in art (Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dalí), music (Arnold Schoenberg), film (several Austrian directors including Josef von Sternberg, Fritz Lang, and Billy Wilder), and literature (Thomas Mann). Eckbo scrutinized both the artistic possibilities in the Los Angeles area and its burgeoning economy and population—which translated into extensive building opportunities. From 1945 on, he began to spend one week a month in Los Angeles: beating the bushes for work and keeping an eye on the projects on the boards and in the ground. For a roof, he used a spare room in the house of Gregory Ain, who would become a fast friend and frequent collaborator. By the end of the year he had secured sufficient work to open the office.

Thus, in late 1946, Garrett and Arline Eckbo moved south; a southern branch of Eckbo, Royston and Williams was opened, renting space for two years from the architect Robert Alexander in the Baldwin Hills Village Golf Club. From the beginning, each office and partner was relatively independent, with quarterly meetings for review and planning. "Mutual respect and cooperation were exemplary," Eckbo remembers. Because of the tight housing market, the Eckbos first rented an apartment in San Pedro, south of the city, but in time found a house more centrally located.[79] Los Angeles was booming, architecture was thriving, and the desire for outdoor living—before the widespread use of air conditioning—was reaching its apogee [figure 37; see plate IX]. The potent combination of peace,

37

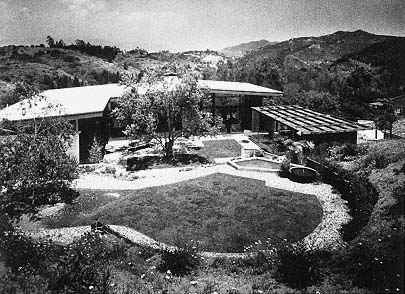

Kiernan garden. Los Angeles, mid-1950s. The openness of the house extends

into the sunny areas—grassed or paved—with trees and a lath house providing

shade. [John Hartley, courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

38

Goldin garden. Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles, mid-1950s. Distinctly shaped

areas of paving, and an irrigated and manicured lawn, contrast significantly

with the natural landscape beyond.

[Courtesy Garrett Eckbo ]

growing prosperity, the relaxation of building material restrictions, and the psychological release from years of austerity—all tinged with personal aggrandizement—made the garden a desirable commodity. The practice flourished, producing garden after garden for clients with existing houses, or in conjunction with housing built to the designs of modernist architects.

In gardens that can be counted in the high hundreds, if not the thousands, Eckbo investigated and reinvestigated the play among space, activity, geometry, climate, and vegetation. The garden's dynamic or more lyrical composition countered the more stolid form of the house and its orthogonal relation to the lot lines [figure 38]. Eckbo "understood that the modern garden had fewer constraints than the modern house, which was concerned with function, efficiency and economy," wrote the landscape architect and professor Michael Laurie. "The garden could be approached much as a sculptor approaches a new block of stone or as a painter, brush in hand, stands before a blank canvas" [figure 39]. The architectonic framework of the garden—commonly built for purposes of physical enclosure or visual screening—structured zones of use and aesthetic space. Vegetation at first played only a secondary role, but in time planting achieved greater prominence [figure 40].[80] Thus, within a handful of years after the war, the elements of Eckbo's mature style were already apparent: staggered, interlocking spaces articulated by a mixture of angled walls, often terminated by a circular space defined by an arcing wall or curving row of trees.