Early Years

Eckbo was born in Cooperstown, New York, on 28 November 1910. His father possessed only limited business acumen and each of his proj-

Garrett Eckbo. Los Angeles, 1959.

[Julius Shulman ]

ects intended to advance the financial security of the family seemed to achieve just the opposite effect.[3] The result was a move west, first to Reno for his parents' divorce, and then to Alameda, California, with a new stepfather. Here the young Eckbo remained through his college years.

Growing up with "limited social opportunities," Eckbo says that he acquired both ambition and direction only after a half-year's stay in distant Norway with his paternal uncle, Eivind Eckbo, in 1929.[4] As he watched the economic and social success achieved through dedicated effort, Eckbo began to consider his options for the future, a future clouded shortly thereafter by the collapse of the international economy. He worked for two years as a bank messenger and at other jobs, attended Marin Junior College for a year, and entered the University of California in 1932. But what discipline should he study?

So I went through the catalog and I found a subject, landscape design, I think it was called then, in the College of Agriculture. And I thought, well, I always used to like to play with plants in the garden, and my mother told me I was artistic, so maybe I should try this .[5]

When Garrett Eckbo entered the University of California, the landscape program was already four decades old. Frederick Law Olmsted had designed the original plan for the then College of California in 1865, when the nascent institution moved to Berkeley from Oakland to escape the corrupting influence of the city.[6] The College of Agriculture added a course in Landscape Gardening and Floriculture in 1913, with John W. Gregg as professor. Katherine Jones complemented Gregg's strengths and interests with an expertise in plant materials. The curriculum intended to provide "both theoretical and practical" instruction, leading toward professional competence. In manner, the program was neither innovative nor retrograde, neither blindly formal nor uncritically informal, educating its graduates at levels commensurate with the national standard. The collapse of the stock market in 1929 and the ensuing depression colored the role of the landscape architecture profession throughout the country, as estate design gave way to public parks, land reclamation, and water management.

More directly influential in the formation of Garrett Eckbo's thinking was H. Leland ("Punk") Vaughan, whose ideas about landscape archi-

tecture contrasted with those of the more senior members of the faculty. A fortuitous meeting with University of California alumnus Thomas Church at Ohio State, resulted in Vaughan's appointment to teach courses in construction, and implicitly, in design. Francis Violich, who graduated from Berkeley in 1934, wrote of Vaughan:

Vaughan (age 25) brought a younger generation's forward looking point of view that provided common ground with the students of those changing times. His broader European and East Coast experience, his understanding of land building relationship, his exposure to modern design ideas, all seemed to turn the department around .[7]

Vaughan's presence thus stimulated in Berkeley students an openminded vision that questioned the complacency of landscape practice in the Far West. He "emphasized economy and clear thinking in the design studio, not as a source of style but as examples of design reflecting time, place, and people."[8] The writings and work of Garrett Eckbo reflect many aspects of Vaughan's philosophy.

Thomas Church, who preceded Eckbo at Berkeley by about a decade, had seen in the Mediterranean countries a source of inspiration and pragmatic parallels to the California condition. Even before the turn of the century the myth of California's Spanish past had played an increasingly influential role in forming the state's architecture. Helen Hunt Jackson's Ramona , published in 1884, described the carefree outdoor life of Mexican-America, the vibrancy of the patio, and the fragrance of the night-blooming vines.[9] By the 1920s a Spanish Colonial Revival was well under way in California, given authority by a 1925 municipal ordinance in Santa Barbara that prescribed buildings in the central district to be designed in idioms recalling Andalusia and other Iberian locales.

In the hands of talented designers such as James Osborne Craig, Lutah Maria Riggs, and George Washington Smith, the Santa Barbara works turned out magnificently, using plays of solids and courtyards efficiently and to great effect.[10] While romantic shopping complexes such as Craig's 1923 El Paseo used meandering paths and architectural mood to evoke mythical memories of Spain, the city's and period's true monument was the Santa Barbara County Courthouse of 1928 by William Moser. In both instances, landscape elements strikingly complemented the architecture, with the red, magenta, or tawny

hues of massive bougainvillea plantings staining the white brilliance of stuccoed walls.

Church's 1927 graduate thesis at Harvard was titled "A Study of Mediterranean Gardens and Their Adaptability to California Conditions," an announcement of Church's professional intentions after the requisite travel in Europe. Fortune brought Church and architect William Wurster together in the early 1930s, and together they developed buildings and landscape for the golf community of Pasatiempo near Santa Cruz. Despite his interest in the Mediterranean countryside, Church's work at Pasatiempo reflected the greatest respect for the native landscape, and his interventions with clipped plantings, lawns and beds, were quite restricted in both scale and exuberance.[11] Later in the decade, as his San Francisco practice began to flourish, Church's designs turned more elaborate, though still tending to rely on the established polite vocabulary of the Italian formal garden. Hedges and parterres of clipped boxwood, axial walkways, and nearly symmetrical dispositions paralleled the decorum of the architectural scheme. While the selection of native and subtropical plant species and a certain relaxed correctness characterized these garden designs, they were still heavily tinted by the manners of the Mediterranean past.

Eckbo recalls that although the University of California's landscape program tended toward a Beaux-Arts doctrine that applied formal ideas to institutional projects and informal ones to residential designs, Berkeley was just a bit too far from its continental sources to maintain true orthodox rigor.

It was a practical, pragmatic philosophy. It was not as doctrinaire as I found later in the East. It was just oriented toward solving problems and preparing students to work in the world the way it was then. It was a limited world in terms of design sources or design inspiration and ideas, which came basically from the movement of the old Beaux-Arts system into the West, where because of the climatic changes and other kinds of local problems, it was forced to become more practical and to adapt.[12]

The power of the California landscape normally diminished the formality of any scheme, softening any overbearingly geometric planting arrangements with an acknowledgment of view and cognizance of

sun and wind—a lesson that would never be neglected in Eckbo's designs.

Eckbo had little contact with contemporary currents in landscape design when he entered college, and no evidence suggests a greater awareness of them when he graduated. He took courses in drawing, plant materials, history and construction as well as studio, and emerged a skilled designer with festering ideas that extended beyond those of quotidian practice. With a wry, tongue-in-cheek title, Eckbo undermined the name of one assignment, if not the actual design [figure 1].[13] A gently undulating entrance road traversed the golf course, transformed into a formal approach to the parking court before the U-shaped country club. Each of the programmatic elements was addressed in a straightforward manner, but no big ideas transcended the assembly of parts.

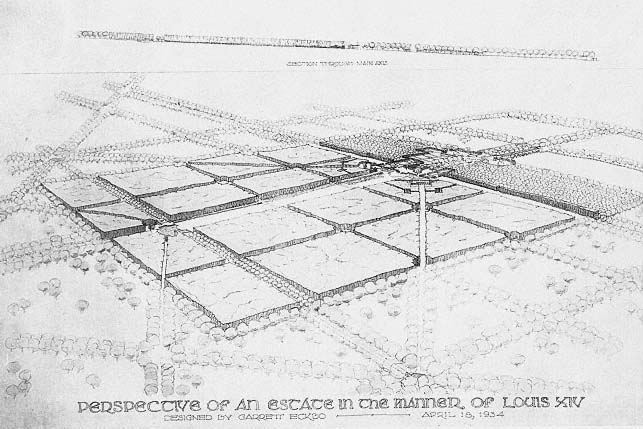

Seen from today's perspective, a third-year student project, An Estate in the Manner of Louis XIV, might be taken as completely ironic—but it was executed in all seriousness [figure 2]. The design was carefully planned and resolved, and a building or colonnade actively terminated the three allées of the trivium . A court formed between them set off the main "château" in a manner reminiscent of the central zone of André le Nôtre's design for Vaux-le-Vicomte from the 1660s. "This was perhaps the best plan I did [as an undergraduate]. . . . I was very interested in history when I was at Berkeley, and I practically memorized the Italian gardens—it wasn't so easy to memorize the French."[14] The first impression of yet another reduced replica of Versailles dissipates with greater scrutiny. While the prevailing central organization, cross axial scheme, and diagonal allées of the patte d'oie hark back to the formal gardens of seventeenth-century France, Eckbo tweaked almost every element of the classical plan, as a mannerist, if not a modernist. Given the openness of the curriculum, the tenor of the American economy, his commissions executed within a year after graduation, and his subsequent social vision, this design remains a complete—and charming—anomaly.

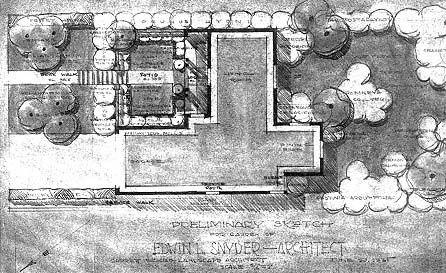

A plan for a small garden for Edwin Snyder [figure 3] demonstrated that the recent graduate could operate competently in more than the classical mode, although the scheme possessed no truly distinctive elements.[15] In many respects the design reinvestigated ideas for

1

Gottrox Country Club, Berkeley. Site plan. Student project at the

University of California, Berkeley, 1935. Watercolor on paper.

[Documents Collection ]

2

An Estate in the Manner of Louis XIV. Aerial perspective. Student project

at the University of California, Berkeley, 1934. Watercolor on paper.

[Documents Collection ]

3

Snyder garden. Rendered site plan. Berkeley(?), 1935. Pastel on diazo print.

[Documents Collection ]

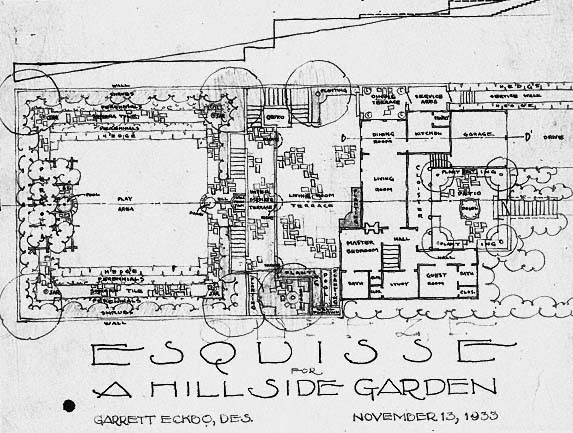

4

Esquisse for a Hillside Garden. Site plan. Student project at the University of California, Berkeley, 1933.

Ink on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

5

Forbes garden. Site plan. Glendale, 1936. Armstrong Nurseries. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

sequential zones characteristic of school projects such as the 1933 Esquisse for a Hillside Garden [figure 4], although its planting scheme was decidedly less rigid. A field of ground cover and two clumps of birches addressed the street, giving on to a rectangular enclosed patio that fronted the house's entry loggia. Masses of ceanothus and other shrubs disguised the borders of the lot to the rear and enveloped an exterior space that served as an extension of the living and dining rooms. Despite this early commission, the depression years were not a good time to enter private practice, and government work comprised almost all the available opportunities for landscape architects.[16] But John Gregg had helped arrange a job for Eckbo in Los Angeles and, a Bachelor of Science degree in hand, in summer 1935 the recent graduate headed south.

Los Angeles was hardly the sprawling, built-up, and smog-laden region it has come to be, and even today Eckbo retains only the fondest memories of his first years in the Southland paradise. He was employed by Armstrong Nurseries in Ontario to design gardens for its clients on sites ranging from the near-palatial to those of very modest dimensions. During his year working at the nursery, Eckbo designed about a hundred gardens, for which the average fee for

6

Flowers garden. Site plan. Temple City, 1935. Armstrong Nurseries. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

design was $10—refunded with the client's first purchase of $25 worth of plants.[17] The drawings for many of these projects remain. As a group they suggest that the landscape architect had already begun to question the notion of styles applied indiscriminately to contemporary California. Set in these terms neither the formal axes of France and Italy, nor massed tree clumps of the English landscape garden, were appropriate to a dry suburban backyard. The schemes also illustrate that relaxed plantings and spaces were beginning to take hold in California, for example, in the work of H. L. and Adele Vaughan. While Eckbo claims that he "hadn't even heard the word modern in connection with landscape design" until he reached Harvard a year or so later, the Armstrong Nurseries designs clearly reflect a simplified organization and a softened formality that would become a strong part of modern landscape architecture.[18]

While we might kindly term these designs contemporary, in no way could they be termed modern. In many of them the flavor of the estate is brought down to the scale of the suburban house. A lawn politely announced the entrance, with shrubs defining the street edge, and trees such as sycamores dignifying the principal facade. The schemes also varied in their degree of formality, at times more rigor-

7

Garden design. Site plan. Location unknown, circa 1936.

Armstrong Nurseries. Pencil on tracing paper.

[Documents Collection ]

ously Moorish, at other times, more fuzzy [figure 5]. For larger sites, a motor court brought the car to the garage and visitors to the front door. Each of the outdoor work spaces—the drying yard and cutting garden, for example—were screened by shrubs, and defined exterior spaces to the south complemented the primary rooms of the house. The orchard, however minuscule, was a common element in many of these works. Although organized rigidly, these tended to be specimen orchards that might contain papaya, citrus, persimmon, orange, avocado, tangelo, and apple trees all in the same grid [figure 6]. Presumably the effect would be less ordered in the reality of maturing trees than in the simple uniform diameter circles shown on the plans, revealing certain contradictions within the design or naïveté on the part of the designer.

The overall planting, in fact, was varied and rich—one might say, overcomplicated and at times, even garish. The linear extension of the house in one unidentified garden design, for example, terminated in a pair of acacias, each flanked by a deodar cedar and announced by a splash of white wisteria—a curious combination of species, to say the least [figure 7]. In some instances the planting schemes ran riot, bringing to a single site lines of myrtle and ranges of eucalyptus.

8

A Country Estate on an Island. Competition entry for a Harvard University scholarship, 1936.

Watercolor on paper.

[Documents Collection ]

Whether this variety stemmed from the young Eckbo's desire to try out as many plants as he could, to see what the more benign (if necessarily irrigated) climate of southern California could uphold, or just reflected the fact that he was working for a nursery—which, after all was in the business of selling plants—we can only speculate.[19] But in his mature years Eckbo never matched in exuberance the planting schemes of his year at the Armstrong Nurseries. His later palette relied instead on an armature of greens enriched by varietals and well placed patches of color.