Human Management

Among the most straightforward examples of psychological expertise used for political purposes during World War II were researchers and analysts who used the tools of their trade to assist public administrators. They did not have to be told to subordinate the goal of knowledge production to that of human management. It was simply understood that war "forces all scientific efforts to short cuts" and that

their job description involved producing tips on how to control people effectively rather than theories that might explain previously obscure aspects of social life.[41]

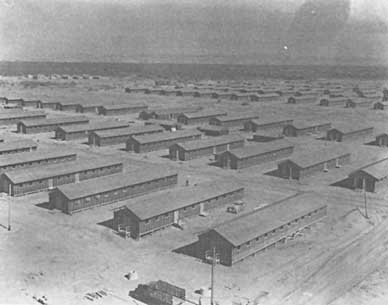

The Sociological Research Project, located in the Poston Relocation Center for Japanese-Americans in the Colorado River Valley, was a clear example of psychology's usefulness in this area (fig. 1).[42] Brought into existence through the forceful advocacy of War Relocation Authority (WRA) consultant Robert Redfield (dean of the Division of Social Sciences at the University of Chicago) and other believers in the administrative value of applied social analysis, the project was directed by Alexander H. Leighton, a navy psychiatrist with some previous field experience in Navajo and Eskimo communities. This innovative research effort was initiated in March 1942, shortly after the decision had been made to intern the 112,000 Japanese-Americans living on the Pacific Coast. The express intention was to experiment with techniques of human management that would prove useful to internment managers and, at the same time, prepare field workers of Japanese ancestry to help with the military occupation that was being planned for various areas of the Pacific.[43] Constructed on the model offered by the Office of Indian Affairs, which had used social scientists as administrative aides in the past, Leighton's research team brought the tools of psychological theory, psychiatric treatment, and cross-cultural research to bear on the management problems at hand. He consciously organized the effort by professional and amateur social scientists (trained in cultural anthropology, sociology, and psychiatry) along clinical lines, "but with the community rather than patients being the subject of study."[44]

Leighton's team members included anthropologists Edward H. Spicer and Elizabeth Colson as well as typists, artists, and translators drawn from among the camp's better-educated population.[45] They specifically disregarded the question of whether the evacuation itself was justified, noting only that "these questions involve matters concerning which data for forming an opinion are not available at present."[46] . They did, however, dutifully apply themselves to helping administrators run the Poston Center and maintained a firm belief that their work would help to uncover the invisible laws of individual and social behavior, thereby strengthening the partnership between science and government.

The greatest promise [of the project] for men and their government, in stress and out of it, is in a fusion of administration and science to form a common body of thought and action which is not only realistic in the immediate sense

Figure 1. Aerial view of Poston Relocation Center for Japanese-Americans,

where World War II experts aided administrators by applying "the psychiatric

approach in problems of community management." Photo: National Archives.

of dealing with everyday needs, but also in the ultimate sense of moving forward in discovery and improved practice. This requires more than hiring social scientists to make reports. It requires an administration with a scientific philosophy which employs as its frame of reference our culture's accumulated knowledge regarding the nature of man and his society.[47]

To this end, the researchers began with a "fundamental postulate" about basic human nature: the psychological self was a universal entity in which many cultural variations appeared. Their assumptions about the psychological status of center residents all followed from their understanding of basic human nature and of fundamental parallels between mass and individual psychology. These assumptions can be summarized as follows: behavior was largely irrational, motivated by emotion and past experience (especially childhood); residents' perceptions of their internment (their subjective "belief systems") were more important than what had actually happened to them (the "objective facts") and whether or not internment was morally justified; dangers

lurked in groups because individual fears and resentments could be kin-died into hysterical and difficult-to-control crowd behavior.

Day to day, the research team conducted intensive interviewing and personality analysis and gathered general sociological data by compiling employment and education records. Staff members prepared oral and written reports that predicted reactions to an array of possible administrative moves and tried to guide management in the directions suggested by their working assumptions. "The administrator who approaches turbulent people with reason is likely to get about as much result as if he were addressing a jungle," was a typical example.[48] While team members could find themselves coping with such humdrum annoyances as unruly teenagers, they tried to concentrate on analyzing and reducing resistance to the overall relocation program as well as to particularly controversial policy suggestions, like registering each camp member for the purposes of a loyalty interrogation. In the latter case, the psychological experts' recommendations were considered important enough to be classified as confidential and circulated at very high policy-making levels.

The picture of the center that emerged from their work was of a community in psychological turmoil, cut off from previous sources of stability, anxious about what other citizens thought of Japanese-Americans, and internally divided along generational, Issei-Nisei lines. Most of all, residents needed a sense of security. Hence, providing it was the surest route to effective administration of the center. When the arrest and detention of two camp residents in a beating incident provoked a general strike at the center, the research team's recommendations helped to defuse mounting tensions quickly and peaceably. Leighton's group pointed out that some administrators' impulse to respond with force rested on a foundation of irrational, racist stereotyping and suggested instead that camp residents be granted more responsibility for maintaining order themselves. The team's recommendations for instilling security through self-government (compiled in a memo written by Conrad M. Arensberg, associate professor of sociology and anthropology at Brooklyn College) won acclaim among high-level policy-makers in the Washington office of the WRA, and resulted in the addition of a community analyst to the staff of every WRA camp in January 1943.

The general conclusions of the Poston team, summarized by Leighton in The Governing of Men: General Principles and Recommendations Based on Experience at a Japanese Relocation Camp (1945), were that human management techniques had to be as psychologically and emo-

tionally oriented as their object. According to Leighton, "Societies move on the feelings of the individuals who compose them, and so do countries and nations. Very few internal policies and almost no international policies are predominantly the product of reason.... To blame people for being moved more by feeling than by thought is like blaming land for being covered by the sea or rivers for running down hill."[49] . The best measures of social control necessarily embodied a sophisticated psychology, since managing people effectively entailed managing their feelings and attitudes, far more a question of engineering self-controls than imposing external punishments.