Preferred Citation: Williams, Joanna. The Two-Headed Deer: Illustrations of the Ramayana in Orissa. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6870073m/

| The Two-Headed DeerIllustrations of the Ramayna[*] in OrissaJoanna WilliamsUNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESSBerkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford© 1996 The Regents of the University of California |

Preferred Citation: Williams, Joanna. The Two-Headed Deer: Illustrations of the Ramayana in Orissa. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996 1996. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6870073m/

Acknowledgments

My research on Orissan palm-leaf manuscripts began in 1979 with a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 1982-83, a Senior Research Grant from the American Institute of Indian Studies enabled me to spend a year in the area of Purl, focusing on this project and participating in the life of one of the great Hindu pilgrimage centers. Subsequent shorter visits were part of my work for the Ford Foundation in Delhi from 1984 to 1986. A sabbatical from the University of California at Berkeley made it possible to see the Dasapalla Ramalila[*] in 1990.

I am grateful to established "Orissa hands" abroad, who were supportive and gave good advice about carrying out research in this part of India: Drs. Hermann Kulke, Eberhard Fischer, Louise Cort, Thomas Donaldson, and Frederique Marglin. At home, my son, Dylan, kept me abreast of the Western artistic genre most comparable to my subject, the comic book.

The people of Orissa who helped in my work should all be thought of as my co-authors. Purna Chandra Mishra of Puri deserves the title Independent Scholar rather than Research Assistant, having been indispensable to many foreign researchers over the years. His wife, Suresvari Mishra, Reader in Sanskrit at Puri Women's College, was of immense help in deciphering manuscripts as well as making me feel at home in Puri. In Bhubaneswar I had the privilege of studying Oriya, the language of Orissa, with Tripti Mohanty, then completing her doctorate at Utkal University and trained as an instructor in the Eastern Regional Language Centre. With lucidity and infectious good nature she gave me insights into local culture that could only come from the daughter of a daitya (Puri temple priest) family Professors K. S. Behera and K. C. Sahu of Utkal University, Professor P. K. Mishra of Sambalpur University, Mr. D. P. Das of the Orissa State Department of Education, and Dr. Dinanath Pathy all generously shared interesting information with me. Without the cooperation of the painters of Raghurajpur, Danda Sahi, and Puri, no serious discussion of their work would be possible. Among my many friends in that community, Jagannath Mahapatra must be singled out as master artist. The hospitality of Sonepur, Asureshvar, and Dasapalla colors my account of rural performances. Finally, I cannot begin to list all the ways I am indebted to Dr. J. P. Das of New Delhi.

In the transformation of a complex manuscript into this book, I am grateful for Stephanie Fay's careful copyediting and dogged pursuit of my idiosyncratic turns of phrase. The entire project might have foundered without the enthusiastic support of Deborah Kirshman as Fine Arts Editor of the University of California Press. And Natasha Reichle has prepared the index with care and good judgment.

Photographs not otherwise credited are my own.

A Note on the Use of Indian Terms

Because my subject is Orissa, I have used the Oriya form for names and vocabulary, which is generally, but not always, the same as Sanskrit (and often distinct from the Hindi forms used elsewhere in India). Hence Hanumana rather than the more familiar Hanuman. In transliteration I follow the Library of Congress system, except in ch and chh (rather than c and ch ), and ri[*] (rather than

Introduction

This book concerns illustrations of the Ramayana[*] , an epic poem with epic implications for contemporary India. I have chosen, however, to focus upon the single region of Orissa—rich rice-growing plains along the eastern coast, between Bengal and Andhra, a region relatively homogeneous, traditional, and peaceful (see maps). Orissa is known for its elegantly carved and architecturally ambitious temples, dating from A.D 600 to 1250. The illustrations considered here, however, are less familiar sequences of pictures from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. My reason for addressing this topic is not that of the mountaineer who climbs a peak "because it is there" (and unclimbed). Rather I should profess a tripartite personal agenda.

First, having spent most of my scholarly career studying the ancient art of South Asia, I was tantalized by questions that seemed unanswerable. For example, in the process of analyzing reliefs of the life of the Buddha from the fifth century A.D. , the Gupta period, I considered earlier images and Buddhist texts as alternative sources for iconography.[1] When neither image nor text corresponded to a particular Gupta carving, it was tempting to credit the sculptor with creating a new version of the story Yet it was also impossible to be certain what verbal guidelines were actually current in written, let alone in oral, form. Comparison required a body of art in which it was clear what written text the artist actually knew and for which oral traditions were preserved. I must admit in advance that the recent material upon which I settled is not without its own problems and includes two genres with potentially different relationships between image and word. Moreover the projection of recent patterns onto the ancient past requires caution. This book presents information essential for that analogy but does not take understanding ancient art as its goal.

Second, having chosen to work in Orissa, I reflected on why interesting and beautiful pictures here had been largely neglected in the overall framework of Indian art, whereas the images of some traditions (e.g. Gupta sculpture or Mughal painting) had been examined and reexamined. A litany of accusations about scholarly biases does not seem to me productive. Yet one of many reasons for such neglect is worth considering—the "folk art" status of the two genres considered here. As I studied both, I found a continuum between rough work, rooted in a

Map 1.

Orissa

2.

Ganjam District

village or popular context, and refined, complex images, some produced by the same artist, others within the same generic form. I became uneasy with the polarization of folk and elite art, even in its Indian formulation, desi (local) and margi (mainstream). Such dichotomies have been uneasily transferred from the realm of verbal lore to that of visual, and the terms merit fuller theoretical analysis. In this book I have deliberately included some images that most art historians would classify as folk art. Part of my hidden agenda is to make both the rough, gutsy and the refined parts of the Orissan pictorial tradition interesting and accessible to a wide audience.

A third incentive to undertake this particular study came in the course of looking at a fine set of illustrations of a poetic text in a museum with a discerning American collector of Indian painting. He remarked as we considered the tenth picture: "What a waste to have these together, where they become boring; each one would be a masterpiece by itself." This reaction is symptomatic of our treating as separate pictures images designed to be seen in sequence.[2]

Formal analysis need be performed on only one member of a set whose style is consistent. Likewise the content of a single picture can be addressed in isolation. But for a series with narrative content, we must consider several images in sequence to understand how the story is told visually Indian illustrated manuscripts have usually been analyzed on the basis of draftsmanship and design in the isolated page. Such qualities need not be neglected. Yet to restrict oneself to them is to omit dramatic qualities such as variety, surprise, and emotional development sustained over a sequence of images. The present study attempts to talk about sequential content without dismissing formal qualities in individual images. My goal is to present this material as interesting even to the collector whose reaction galled me, and at the same time to demonstrate that the pictures have another dimension, missed if one is seen in isolation. This task is not peculiar to Orissa, so I focus upon images of the epic Ramayana[*] , some version of which is known to virtually every Indian and which ought to have a place in the world's literary canon.

For methodological guidelines, three comparisons between pictures and other sequential art forms come to mind. The first is cinema, a medium that comprises sequential images as well as words and other sounds. However fine the photography, it would be difficult to judge a movie from isolated frames, omitting other "filmic" qualities. My own experience of Indian culture began with the films of Satyajit Ray What captivated me most in the Apu trilogy was the unfamiliar mixture of emotions depicted and evoked, the sense that one could move rapidly back and forth between grief and amusement. My bafflement at so meandering a plotline perhaps reveals the limitations of a viewer raised on American cinematic aesthetics in the 1950s. When I eventually read Bibhuti Banerji's novel, on which the movies were based, I realized that Ray had tightened up the plot and reduced the number of emotional reversals. Nonetheless, I would claim that the films do reveal a structure based on the development of several complementary moods, the rasas that will figure m my own analysis, which contrast with an Aristotelian preoccupation with plot or structure based on a coherent sequence of action.

A powerful film concerning contemporary life in Orissa, the very region of this book, suggests an analogy with the pictures discussed here. The title of that movie, Maya Mriga (The Magic Deer), alludes to a theme in the Ramayana[*] central to this study In the film, the deer is an emblem of the illusory nature of traditional family values, such as respect for parents and support for siblings, in an age when education (itself traditionally valued) encourages the young to put themselves first. Unfortunately that film is not easily accessible to an English-speaking audience, so I shall not pursue the comparison. The immensely popular version of the Ramayana[*] shown on Indian public television in 1987 and 1988 will be more familiar to many readers; thus references to the TV series occur throughout this book.

Finally, one must note that cinema and video are usually more collaborative media than the painting and book illustration considered here, even in the case of a strong director such as Satyajit Ray, who guided both photography and music with care. Hence the analogy is not inevitably useful as a means to understand the production of images. Furthermore, the existence of a film, like theater, in time that is not reversible (despite the existence of the video cassette) gives it a different status from pictures whose order the viewer participates in determining.

The comic strip forms a yet more apt comparison for the illustrated book. One might argue that today's most vital sequential graphic art form is the comic, both in India and in the West.[3] In the Orissan book, the same artist normally executes pictures and text, and the text is presumably copied from another manuscript. The comic, likewise, may be produced by one artist, although many comics result from collaboration between artist, author, and letterer. The fact that the Western comic usually presents a new story makes recognizability a major issue, whereas any images of the Ramayana[*] have an initial legibility As the distinguished man of letters A. K. Ramanujan has put it, no Indian ever reads the Ramayana[*] for the first time.[4] Nonetheless, the interpretation of its depiction requires the reader's cooperation. Thus it seems fruitful to bear in mind several devices of the comic throughout this book: framing, the spectator's position, and variations in the number and size of panels to indicate the passage of time.

A third tradition analogous to narrative images is purely verbal narrative. This comparison is perhaps most promising as a source of theoretical models, having attracted the most attention. The burgeoning field of narratology provides frameworks rooted in literary criticism but readily applied to pictures that tell stories.[5] Some Westerners and educated Indians may feel that because older images do not tell stories clearly to us, they were not intended to tell stories at all. One could counter, however, that the stories were clear to the knowledgeable.[6] One could also argue, as I do, that clarity is not the only possible goal of a story. In Chapter 51 shall attempt to construct a narratological framework suited to Indian pictorial images.

Here I shall simply sketch some elements of the theoretical models from literature that I do find useful and not specific to Western culture. In the first place, the Russian formalists have distinguished story (the underlying "argument" or chronological sequence of events) and discourse (the form in which argument and events are actually presented).[7] When we turn to images, it would be easy to reduce these concepts to a verbal story and a visual discourse, but it is worth remembering that there is also a discrepancy between the two at the verbal level and hence that the text illustrated need not constitute the story. The story in fact lies in the mind of the artist, and its retrieval requires looking at the pictures in addition to reading the accompanying words. In this book, pictorial discourse is the primary concern.

Roland Barthes begins his seminal essay, "The narratives of the world are numberless" and I admire his generally pluralistic vision of the subject.[8] Barthes notes the fallacy described in the scholastic formula post hoc, ergo propter hoc , linking consecution (order) and consequence (causation). He also remarks that elements in a story may have a phatic role, that is, communicate feelings rather than ideas. Most important for me, Barthes provides an exemplary framework in which

narrative structure functions as a code, limiting but not determining the tale that ensues.[9] In other words, he admits the freedom of the artist, which I find particularly necessary in dealing with Indian traditions too readily treated as formulaic. Thus he avoids both mechanical classification of imagery and complete ram domness.

Gérard Genette, in focusing on one major novel, Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu , provides a large body of analytic concepts.[10] These seem most helpful in considering the temporal dimension of the story, and my discussion of matters of order is indebted to him. Hence the terms "anachrony" (departure from chronological order), "analepsis" (flashback), and "prolepsis" (flash-forward). Matters involving the narrator, which Genette classifies as mood and voice, are more problematic in the realm of pictorial narration in general. His term "focalization," roughly identified with a narrative point of view, has been questioned but not discredited, and visual equivalents have been suggested.[11] Given the broad impersonality of Sanskrit literature, I consider our stories as "nonfocalized" in general, but the concept may he helpful in several cases where an entire sequence is presented as an illusion.

In organization, the present work takes on some of the labyrinthine complexities of Indian storytelling. I have been tempted at points to separate out entirely my different concerns for various readers. But I do not want the student of art history to be able to bypass the rich Indian stories. Nor do I want the student of Indian literature or of narratology to be able to bypass the visual adventure of Orissan pictures. Chapter 1 presents a variety of verbal versions of the story of Rama. Chapter 2 introduces Orissan painting and manuscript illustration as a whole in traditional formal, historical, and contextual terms, as they survive from the late eighteenth century on. Chapter 3 addresses earlier sculptural images of the subject of Rama in the same region, as a visual precedent for the pictures. Chapter 4 compares systematically the diverse pictorial versions (our discourse) of ten events in the story. Chapter 5 considers each pictorial discourse in sequential terms, returning to theoretical issues. Chapter 6 attempts to draw conclusions about meaning, indeterminate as that may be, about the artists' storytelling choices, and about our judgment of the success of the pictorial narratives.

Finally, I feel compelled to underscore a philosophical point that might be lost, coming from an art historian telling a complex, pluralistic story that suggests complete relativism. The fact that we all make mistakes is trivial but true. This is comparable to pointing out that there are germs everywhere; we are not therefore justified in performing surgery in a sewer. There are mistakes as well as germs, and I would like to minimize both. But it does interest me that two or more answers to one question may be correct. This modified form of relativism underlies my argument in several ways.

1

The Story

A Resume[*]

Any discussion of variant tellings and depictions of the story must presuppose some familiarity with a basic version of the plotline. Because no Indian hears the Ramayana[*] for the first time, Indians and adoptive Indians (South Asian specialists) will not need the following résumé. This prelude is intended for Western readers venturing into a new field. To follow theoretical issues, we cannot remain outsiders and must begin like children with a fairy tale. The following bare-bones account, devoid of interpretive comment, is limited to the gist of the Sanskrit epic that is relevant to later versions current in Orissa. Illustrations from a manuscript discussed in Chapter 2 are included here because they depict clearly and directly many parts of the plot. They are part of an Orissan précis of the tale, the literal translation of which appears in Appendix 3, and thus a few incidents in our résumé are not depicted while others are added. Traditionally the story of Rama is divided into seven epic chapters, or kandas[*] .

I. Bala Kanda[*]

Once upon a time, Dasaratha, King of Ayodhya, lacked a son. The sage Risyasringa[*] , induced to leave his forest retreat to bring rain to a neighboring kingdom (Figure 1), also performed a sacrifice for Dasaratha that yielded a fertility-inducing porridge (Figure 2). Dasaratha distributed this to his three wives (Figure 3): Kausalya gave birth to Rama, Kaikeyi to Bharata, and Sumitra to the twins Laksmana[*] and Satrughna (Figure 4). After a few years the sage Visvamitra came to the court to ask Dasaratha to lend him Rama, in order to destroy demons who had been attacking the sage's sacrifices. This Rama did, accompanied by his favorite brother, Laksmana[*] (Figure 5). His youthful exploits, beginning with killing the demoness Tadaki[*] (Figure 6) and attacking other obstructors of the sage's sacrifice (Figure 7), demonstrated his role as an incarnation of the god Visnu[*] come to earth ultimately to destroy the chief demon, ten-headed Ravana[*] . The youthful Rama released Ahalya, a beautiful woman, from a curse (Figure 8). He also stopped in the court of King Janaka, where a test was under way for the hand of princess Sita ("Furrow," because she was born from the earth); various princes were attempting to bend

Figure 1.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (courtesy National Museum of Indian Art, New

Delhi, no. 72-165/I). Performer begins, Risyasringa[*] brings rain, f. 97r.

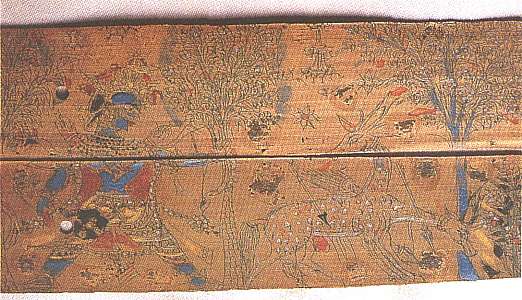

Figures 2, 3.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 97v: (top) Risyasringa[*]

performs sacrifice for Dasaratha; (above) Distribution of porridge to queens.

the mighty bow of the god Siva. Rama alone was able to perform this feat (Figure 9) and thereby won Sita as his wife (Figure 10). On the way home he encountered the powerful ascetic Parasurama and was again challenged to bend a supernatural bow. Rama succeeded and as a warrior (ksatriya[*] ) proved himself equal to the priestly (brahman) avatar of the same god Visnu[*] (Figure 11).

II. Ayodhya Kanda[*]

Back in Ayodhya, Dasaratha prepared to crown prince Rama as his successor. At that moment, egged on by her servant Manthara, the second queen, Kaikeyi, chose to redeem a boon the aged king had granted her in his youth (Figure 12).

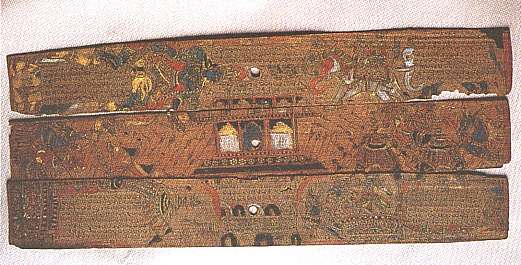

Figures 4, 5.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 98r: (top) Birth of Dasaratha's

sons; (above) Visvamitra takes Rama and Laksmana[*] .

Figures 6, 7.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 98v: (top) Death of Tadaki[*] ,

Visvamitra's sacrifice; (above) Rama fights the demons Subahu and Maricha.

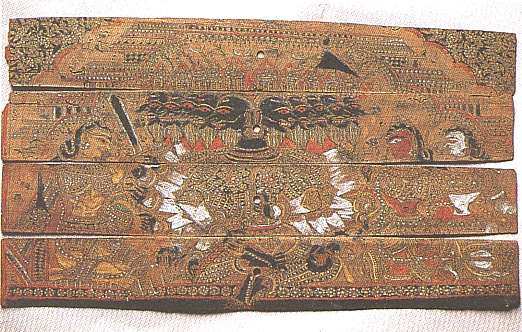

Figures 8, 9.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 99r: (top) Ahalya released from

curse, Boatman washes Rama's feet; (above) Rama, at Janaka's court, bends

Siva's bow.

Figures 10, 11.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 99v: (top) Rama and Sita's

marriage; (above) Meeting with Parasurama, Preparations for Rama's coronation.

Figures 12, 13.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), 100r: (top) Manthara,

Dasaratha and Kaikeyi; (above) Rama's exile, Chitrakuta[*] Hill.

Figures 14, 15.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 100v: (top) Rama shoots

the crow; (above) Bharata's visit to Rama, The heroes confront the demon

Viradha.

Figures 16, 17.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 101r: (top) The sage Atri

and his wife, Anasuya, welcome the exiles; (above) Surpanakha[*] denosed, Her

demon brothers.

Dasaratha was thus compelled, against his will, to crown her son, Bharata (absent from court at the time), and to exile Rama to the forest for fourteen years. Rama acceded dutifully to this plan and departed with Laksmana[*] and Sita, settling first on the charming mountain Chitrakuta[*] (Figures 13, 14). Dasaratha died of grief. Bharata returned to Ayodhya in horror at his own succession and proceeded to visit Rama in an unsuccessful effort to bring back the rightful king (Figure 15). Bharata agreed to rule in his brother's name, setting Rama's sandals on the throne that had been moved in mourning to a village near Ayodhya.

III. Aranya[*] Kanda[*]

Dwelling in a wilder part of the forest (Figures 15, 16), Rama and Laksmana[*] encountered various demons, including Surpanakha[*] the sister of Ravana[*] , the ten-headed demon king. She assumed a beautiful form but failed to seduce the two heroes. In fact Laksmana[*] cut off her nose and ears in a traditional gesture of disrespect (Figure 17). Surpanakha[*] sought redress from her brothers, first Khara, whose forces Rama defeated, then the elder Ravana[*] . This ruler persuaded the demon Maricha to take the form of a golden deer, which enchanted Sita (Figure 18). Rama went off to hunt it, leaving his wife in his brother's charge in a forest hut. Shot, the deer cried "Laksmana[*] " in Rama's voice, and Laksmana[*] was compelled to assist his brother, leaving Sita alone. Then Ravana[*] appeared in the form of a mendicant, lured her from the hut by appealing to her pious generosity, and carried her away in his aerial chariot, Puspaka[*] , to his golden citadel, Lanka[*] (Fig-

Figures 18, 19.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 101v: (top) The demon

Trisiras, Magic deer; (above) Sita's kidnap, Jatayu's[*] attack.

Figures 20, 21.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 102r: (top) Sita in Lanka[*] ,

Rama returns to hut; (above) Rama swoons, meets Jatayu[*] .

ures 19, 20). On the way, the divine vulture Jatayu[*] attempted unsuccessfully to stop the abduction and fought with Ravana[*] . Found dying, this bird informed the brothers what had happened (Figure 21). Rama was stricken by intense grief.

IV. Kiskindha[*] Kanda[*]

The brothers entered Kiskindha[*] , the realm of the monkeys, a forest filled with demons such as the headless Kabandha, with tribal hunters, and with sages (Figures 22-24). They were approached by Hanumana, general of the ruler Sugriva, who had received Sita's jewels as she was flying and was hence alerted to the crisis (Figure 25). Sugriva had occupied the throne of Kiskindha[*] while his elder brother Valin was presumed dead but was banished when the brother returned. Rama demonstrated his power as equal to the task of helping Sugriva by kicking the body of the giant Dundubhi, Whom the mighty Valin had killed, and by shooting through seven trees with one arrow (Figure 26). Then Sugriva challenged Valin to a fight, in which Rama, hidden behind a tree, eventually shot Valin. During the subsequent rainy season Rama grieved on Mount Malyavan (Figure 27), and Sugriva celebrated his own restoration by drinking. Finally the monkeys searched in all directions and discovered that Sita had been taken to Lanka[*] .

Figures 22, 23.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 102v: (top) The demon

Kabandha with Rama, Laksmana[*] ; (above) Rama and Sabari (tribal woman),

Cowherds.

Figures 24, 25.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 103r: (top) Rama meets

ascetics; (above) Rama meets Hanumana, Sugriva.

Figure 26.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I): (top) Rama shoots through seven

trees; (above) Rama kicks Dundubhi's bones, Death of Valin, f. 103v.

Figures 27, 28.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 104r: (top) Rama on

Mount Malyavan; (above) Hanumana goes and returns.

V. Sundara Kanda[*]

Hanumana leapt across the ocean, evading various demons, to reach the citadel of Lanka[*] , where he assumed a tiny form to spy on the demons' life. He delivered a ring from Rama as a token to Sita, imprisoned by demonesses in a grove of asoka trees. She affirmed her willingness to wait for rescue by Rama. Hanumana in heroic form wreaked havoc on the demon citadel and was captured by Ravana's[*] son Indrajita. The monkey's tail was bound with rags soaked in oil and set on fire, at 'which point he escaped and used his flaming tail as a torch to set the buildings of Lanka[*] ablaze. At last he and the monkey search party returned to Rama (Figure 28).

VI. Yuddha Kanda[*]

Rama and his monkey allies camped by the straits of Lanka[*] , where the demon Vibhisana[*] , having tried to persuade his brother Ravana[*] to return Sita, defected from the demons' side. The monkeys constructed a causeway of boulders across the ocean and the army marched to Lanka[*] (Figure 29). The battle began with personal combat between. Sugriva and Ravana[*] , after which various diplomatic efforts and ruses ensued. The fighting warmed up, magic weapons playing a vivid role (Figure 30). Ravana's[*] giant brother Kumbhakarna[*] had to be wakened from six months' sleep, to which he was entitled each year, and he destroyed countless monkeys before he was slain by Rama (Figure 31). Indrajita incapacitated Rama and Laksmana[*] (Figure 32), who were resuscitated when Hanumana flew to the Himalayas and brought back Mount Gandhamadana together with the medicinal

herbs that grew there (Figure 33). Indrajita was ultimately killed by Laksmana[*] and Ravana[*] by Rama (Figure 34). Sita could not be reunited with Rama until she performed an ordeal by immersing herself in fire. Emerging unscathed, she demonstrated that she had remained faithful while in another man's house (Figure 35). Vibhisana[*] was crowned in Lanka[*] (Figure 36). At last Rama and Sita returned to Ayodhya for his coronation (Figures 37-40).

Figure 29.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I): (top). Building the bridge; (above)

Attack on Lanka[*] , f. 104v.

Figures 30, 31.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 105r: (top) Garuda[*] rescues

Rama and Laksmana[*] from serpent-arrows; (above) Death of Kumbhakarna[*] .

Figures 32, 33.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 105v: (top) Laksmana[*]

wounded; (above) Hanumana brings mountain, watched by Bharata.

Figure 34.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I). Death of Ravana[*] ,

f. 106r.

Figures 35, 36.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 106v: (top) Sita's test;

(above) Coronation of Vibhisana[*] in Lanka[*] .

Figure 37.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 107r: (top) Return to Ayodhya;

(above) Coronation of Rama.

Figure 38.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 107v: (top) Lavanyavati[*] watches

(above) coronation of Rama.

Figure 39.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 108r: (top) Lavanyavati[*] watches

(above) coronation of Rama.

Figure 40.

Round Lavanyavati[*] (NM 72-165/I), f. 108v: Lavanyavati[*] (above )

watches performance (top ).

VII. Uttara Kanda[*]

The final book includes diverse stories about the earlier life of the principal actors, as well as seemingly unrelated episodes. It also includes a most problematic sequel to the story. Because of popular doubts about Sita's fidelity, Rama felt compelled to send her into exile. There she took refuge in the hermitage of the sage Valmiki and gave birth to Rama's twin sons, Lava and Kusa. Rama performed a horse ceremony, the traditional perquisite of an emperor, and was challenged by these two boys, who recited the family's story, the Ramayana[*] as composed by Valmiki. Rama recalled Sita, but she returned to her mother, the Earth. And Rama returned to heaven as the god Visnu[*] .

Litterary Versions of the Ramayana[*] In Orissa

That there are many Ramayanas[*] has been acknowledged in a number of recent essays.[1] The remainder of this chapter presents those verbal versions of the story that seem relevant as background to Orissan pictures, which are the main concern of my book as a whole. First the written texts. The reader is advised not to expect a complete survey of versions of the epic, even in Oriya. Such surveys have already been made, and the student of literature may consult the following works directly: K. C. Sahoo, Oriya Rama Literature —an authoritative, detailed description of the full range of texts by an Oriya scholar;[2] ç K. Bulke, Ramkatha (Utpati aur Vikas )—a magisterial Hindi survey of all kinds of Indian and Southeast Asian written texts;[3] ç W. L. Smith, Ramayana[*] Traditions in Eastern India —a selective and provocative treatment of Assamese, Bengali, and Oriya versions.[4] ç

Literature may of course play a variety of roles in relation to visual imagery. Some works might be termed "canonical;' as the Bible is for Christian art; that is,

they may provide a relatively standardized framework of orthodoxy[5] While Valmiki's Sanskrit Ramayana[*] has been accorded this status, this text itself varies considerably with time and place, and it may have been too inaccessible or unfamiliar to have played a canonical role in fact, although Valmiki's name is revered. A second role that literature plays is as a text explicitly illustrated. Here Orissan manuscripts of the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] and the Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] that include pictures are obvious examples. Likewise for at least one set of paintings by professional painters we have a short, popular poem that the artist set out to illustrate, verse by verse. But the third role of literature is more amorphous arid significant: it may provide a familiar and hence influential version of a story to which the artist has been exposed. Here the long Ramayana[*] of Balarama[*] Dasa, read sequentially in temples and available in many villages in the form of unillustrated manuscripts, may have had a powerful, if not "canonical," impact. Similarly, various performed versions, departing from this as well as from Valmiki and other texts, are a potent source of artistic imagery Nor, finally, should the relation between texts and images be viewed as deterministic or one-way. Surely at times verbal stories reflect pictures that the teller has seen. With all these complexities in mind, it is worth situating some relevant literary traditions briefly, before turning to the images.

Valmiki

If one asks an Oriya, or for that matter any north Indian, today, "Who wrote the Ramayana[*] ?" the answer is almost inevitably Valmiki. This sage's role is encoded in many versions of the story, which begin with the killing of a male krauñcha bird while it was making love. Valmiki was moved by the sorrow (soka ) of the mate to recite a verse composed of thirty-two syllables, the meter (sloka ) of the great epic itself. And in most versions of the last book, when Sita is banished, it is Valmiki's hermitage where she takes refuge and where her sons Lava and Kusa are born and raised. Hence his place as the composer of the tale.

The modern scholar, armed with techniques of textual analysis as well as with practical skepticism, is aware that all seven volumes are hardly the work of a single author, and one may question the historicity of Valmiki himself. It has long been felt that the core comprises books two through six, the Ayodhya through Yuddha Kandas[*] . These probably originated in the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. , whereas books one and seven (the Bala and Uttara Kandas[*] ) were added between the third century B.C. and the first A.D. [6] The method of transmission was exclusively oral at first, with some mnemonic devices that counteracted the inevitable process of diversification. Textual scholars recognize broadly differing northern and southern recensions, from which a critical edition has been constructed in the past thirty years.[7] ç Within the former, western and eastern recensions can be discerned, the second most relevant for us.[8] ç At the same time, we may in fact consider the seven volumes as a whole and ascribe them to Valmiki, simply because they were not critically differentiated by the Orissan public in the eighteenth century and later.

The sequence of events recited in my résumé is that of the Valmiki text of eastern India, found also in many later versions to be considered in more detail.

The Sanskrit, while at times self-contradictory and open to criticism, seems to present two broad concerns. One is moral—the role of the principal characters as ethical models. Thus Rama's nature, perhaps two-dimensional to Western eyes, is built around his generally unemotional acceptance of demands made by higher authority, including the abandonment of his kingdom and, ultimately, of his wife. Occasional lapses, such as the slaying of a woman (Tadaki[*] ) or the use of a ruse to kill the monkey king Valin, have been met with a rich array of Indian analyses and explanations. Likewise Sita, Laksmana[*] , Hanumana, and other actors serve as models of Indian social values, which may explain the enduring popularity of the epic as well as the urge to adapt it to modern circumstances.

A second concern is aesthetic and, paradoxically, emotional. The Ramayana[*] is identified as the Adikavya, or first example of High Poetry, a status that derives less from its technical poetics than from the broad sense of mood. While Rama himself grieves remarkably little at his own travails, the story itself is built around the emotion of sorrow (karuña rasa ), which informs major moments and hence is imparted to the audience.[9] Others among the nine standard moods—the heroic, the humorous, even the erotic—are brought in, but it is the pathetic that prevails. Thus our mythical author, or rather the text itself as it has evolved, shows a general aesthetic intent that unifies diverse stories of palace intrigue and fairy-tale exploits in the jungle.

It has been argued that this Sanskrit text provides a basic framework for the vernacular poems of eastern India, which only explain, reduplicate, resolve, apologize for, and in minor ways elaborate upon Valmiki to reflect various later concerns.[10] Indeed there are Oriya transliterations of Valmiki,[11] ç and he is invoked as the originator of the story in most Oriya versions discussed below. The great sixteenth-century Orissan poet Balarama[*] Dasa refers to pandits in his day reciting Valmiki's text.[12] ç

Yet granting its moral and aesthetic power, I find it difficult to accord Valmiki's Sanskrit a consistent role in directly guiding later literary versions of the Ramayana[*] , let alone visual ones. This objection derives partly from my focus upon authors such as Sarala Dasa and Upendra Bhañja, who depart substantially from Valmiki's framework. I am struck by the ease with which Valmiki is invoked today by people who have in fact not read the Sanskrit or even a complete translation of it into some modern language. In short, my picture of the role of Valmiki for Orissan artists is similar to the one attributed to him in the television version of the epic that captivated India in 1987 and survives in the form of videocassettes.[13] Each episode acknowledges the sage as the original author, and there is no suggestion of explicitly departing from his version for any reason. This acknowledgment does not indicate complete familiarity with the Sanskrit, although undoubtedly the television producer and his advisors knew some version of Valmiki's text. But they also drew upon a variety of other traditions, including a wide range of vernacular versions explicitly invoked in the cause of national integration. Nor does respect for Valmiki rule out innovations like those of past retellers of the story. If one is struck that more of the vernacular versions corresponds to Valmiki than to any other ancient source (such as Jain variants that present a substantially altered structure), that may be because Valmiki's Sanskrit preserves a consensus version of other written as well as oral Rama stories. These must collectively be taken as

the source for later authors and indeed for most people in a society where writing did not have its present normative status. We would be deluded to search for a single model or to privilege one, whatever its classical status.

Later Sanskrit Versions

Recasting the story in Sanskrit did not stop with the epic that bears Valmiki's name; many literary and religious versions are known. I shall focus on two that were illustrated in Orissa. The first is of pan-Indian significance—the Adhyatma ("Supreme Spirit") Ramayana[*] , one of a class of short Sanskrit works composed with later devotional and philosophical concerns. This has been ascribed to the fifteenth or early sixteenth century and is associated with Banaras in particular.[14] The impact of the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] on vernacular writing is widely recognized, not only on Tulsi Das's Ramcharitmanas , as one might expect from the composition of that influential Hindi poem in the same place a few decades later, but also on works in tongues as distant as Malayalam.[15] ç The major Bengali Ramayana[*] by Krittibasa[*] , similar in some ways, may have been composed slightly earlier; yet elements that it shares with the Ramcharitmanas seem to be interpolations into the unusually elastic Bengali text. Similarly we shall hear more of the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] as a source for Oriya writers.

The Adhyatma Ramayana[*] may be understood as a condensation of Valmiki, leaving out those matters that do not focus; upon Rama, with three broad additional concerns. First, this is a work of monastic Vedanta philosophy, for which all phenomena are dependent upon the world soul, or brahman, here equated with Rama himself, who is undifferentiated, without attributes (nirguna[*] ). Thus events are preordained. For instance, Manthara does not act from her own evil to prevent Rama's coronation but is impelled by the goddess Sarasvati (2.2.46). Illusion, or maya, in this system characterizes everything. The epitome of this principle is the order Rama gives Sita, as he departs to hunt the illusionary deer (maya mriga[*] ), that she hide her true self in the fire inside the hut and create an illusionary form (Maya Sita) that will be kidnapped by Ravana[*] (3.7.3-4). Thus his own grief at her loss is feigned, even to his brother, and the story is robbed of direct tragedy. At the same time, the tale assumes a rich phenomenological irony Maya Sita had previously appeared as a motif in earlier texts, such as the Kurma and Brahmavaivarta Puranas[*] reflecting concern with Sita's purity. But illusion plays a larger role in the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] as a consistent principle that undercuts the actual plot.

Second, this text is informed by bhakti, or a devotional attitude toward Rama, who hence becomes more a god and less a mere human. This attitude is visible in a good deal of later Ramayana[*] literature and is comparable to the development of devotion to Krisna[*] in north India, but here the devotee is seen predominantly in the stance of a servant, rather than that of a lover, unlike Krisna[*] with his female followers, the gopis. The Adhyatma Ramayana[*] is associated with the Ramanandin sect of ascetics (sadhus ), for whom the preferred name-ending Dasa (servant) indicates the ideal of humility.[16] At the same time in the Adhyatma, Rama becomes more than one of a number of avatars, is equated with Visnu[*] himself, and at times seems to transcend even Visnu[*] .[17] ç The result is to create a tension between the

Vedanta philosophical context, in which even the ultimate reality of Rama as an actor in the world should logically be called into question, and the devotional urge to emphasize his exploits.

Bhakti is visible in the way in which the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] presents Rama as delivering to salvation those whom he kills, for example the demon Maricha (3.7.22-25). Moreover, devotion is explicit in a number of hymns of praise inserted into the text, such as the encomium uttered by Ahalya when she is released from the form of a stone (1.5.43-64). The best known of these passages, the sermon preached by Rama as chapter 5 of the last book known as the Ramagita (imitating the Bhagavadgita ), is probably older than the text as a whole.[18]

Third, the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] incorporates Saiva and tantric elements, again producing some contradictions with the philosophical and devotional aspects of this work. The framework, in which the story is told by Siva in answer to Parvati's questions, may not in itself be of great significance, for it is part of the status of the text as a Purana[*] . Before the bridge to Lanka[*] is built, Rama installs a liñga on the shore and worships Siva, presumably a nod to the actual shrine at Rameshvaram (6.4.1-4). One is reminded that this text served the Ramanandins, a Vaisnava[*] sect centered in Benares, the abode of Siva. Similarly, tantric or Sakta elements have been discerned, although it may also be argued that sakti is fundamentally conceived here as Rama's maya , occasionally acting through Sita but not an independent feminine force of creation.[19] The text is in general complex and reflects conflicting currents, like most documents of Indian religion.

The popularity of the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] in Orissa is indicated by its repeated translation into Oriya between 1600 and 1900. Of the translations, the one most frequently illustrated was that of Gopala Telenga, made in the middle of the eighteenth century.[20] Gopala, a Telugu speaker as indicated by his name, was a brahman who served at the court of the ruler Ajit Sinha in Sambalpur. His is not entirely a literal translation of the standard Sanskrit text. For example, Ravana[*] takes not only Sita but also her entire hut to avoid touching her, a motif that appears elsewhere to minimize the possibility of her pollution. Most significant, at the beginning of each book Lord Jagannatha is invoked, and in the sixth, the Yuddha Kanda[*] sixty verses are added in his praise. In the same way that Siva could be accommodated in the original text, the principal god of Orissa could be brought into this vernacular translation.

The Brahma Ramayana[*] is a second and far less widely known Sanskrit work, not composed in Orissa but extant in two copies there, one of which is illustrated.[21] Both of these manuscripts are in simple Sanskrit, not translated but in Oriya characters, like most Oriya copies of the Gita Govinda, which was easily understood in the same form. Elsewhere the text exists in Devanagari script.[22] ç It appears to be part of a larger work called the Brihatkosala[*] Kanda[*] and to have fallen into three portions—Rama's Lila the marriage of Rama and Sita, and then additional play or Lila .[23] ç The Ramayana[*] plot is minimal, although the episodes of Ahalya and Tadaki[*] do appear in the illustrated Orissan version. The bulk of the text, however, concerns Rama's sport with a number of women. There is strong resemblance to Krisna's[*] relationship to the cow-maidens (gopis ), in which the seemingly erotic relation to the godhead is in fact a form of ecstatic devotion appropriate to

male followers as well as female. The elaborate description of rasa (rustic dance) dominates this text, as in many Krisna-ite[*] works.[24] Thus the Rama-bhakti of the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] is taken one step further in such a work.

Early Oriya Texts

In addressing the textual sources of Orissan pictures of the Ramayana[*] , it would be impossible to omit two monuments of early Oriya literature, even though neither has, to my knowledge, been directly illustrated. Both Sarala Dasa's Mahabharata and Balarama[*] Dasa's Jagamohana Ramayana[*] are so well known and widely revered that we may presume most artists in the region would have had some familiarity with them.

The Adikavi, or Father of Vernacular Poetry in Orissa, Sarala Dasa, active probably in the third quarter of the fifteenth century, is famed for his Mahabharata .[25] This work draws upon oral traditions, including elements that also crop up in different form in various Sanskrit works.[26] ç It was followed by three more or less literal translations of the epic, none of which equalled Sarala's[*] in popularity. The poet is identified as a sudra, a peasant whose brother was a ferryman, a status that is; in keeping with the rural language and earthy flavor of his work. For instance, Siva's worship as the liñga is explained with a story that he shocked his mother-in-law by addressing her naked at the time of a ceremony, so that she cursed him to be worshiped in the undignified form of a phallus.[27] ç Likewise local touches are only to be expected—for example the enlargement of the story of the tribal Ekalavya, who, in the guise of the Sabara Jara, kills Krisna[*] and follows his unburned body to Purl, where it becomes Lord Jagannatha.[28] ç

Like the Sanskrit Mahabharata, Sarala Dasa's poem includes a version of the story of Rama that is yet further removed from Valmiki. Here again some details occur in other versions, such as the explanation of Surpanakha's[*] anger with Laksmana[*] for having decapitated her son Japa while he was meditating in an anthill.[29] Rama is said to be reborn as Krisna[*] , and Laksmana[*] (who is also an avatar of Siva) as Balarama[*] , linking various strands of plot and religion. Some elements are shared with the Bengali tradition, such as the inclusion of multiple forms of Ravana[*] killed in different ages.[30] ç Sarala Dasa's expanded accounts of the ascetic Risyasringa[*] , of the magic deer, and of the incident of a milkman who feeds the heroes in the forest are discussed below in connection with their illustrations.

Balarama[*] Dasa worked some forty years after Sarala and is usually viewed as part of the Oriya entourage of the great Bengali Vaisnava[*] reformer Chaitanya, who visited Puri in 1510. In fact his lengthy version of the Ramayana[*] seems to have been completed in 1504 and is not directly influenced by Chaitanya.[31] His supposedly frenzied religious devotion, along with tales of the entire group of Oriya saints known as pañcha sakhas (five companions of Chaitanya), may be a later fabrication. In a colophon he is identified as the son of the minister of a ruler and as a karana[*] (scribe).[32] ç Thus he belonged to what was in fact quite a high-placed subcaste in Orissa, although technically he was a sudra, part of the lowest of the four major ranks of Hindu society, a position emphasized by followers of Chaitanya in view of the ideal of humble servitude. In general his brand of Vaisnavism[*] , centered on Jagannatha, is rooted in Orissa in the late fifteenth century.

Balarama[*] Dasa puts his story in the mouth of four different narrators, framing the epic in a complex way like the Ramcharitmanas .[33] Indeed he honors Valmiki as the first narrator on earth, and his Jagamohana Ramayana[*] (also known as Dandi[*] Ramayana[*] , from the meter) includes most of the variants of the eastern recension of Valmiki, such as the story of how the demon Kalanemi attempted to deter Hanumana from visiting Mount Gandhamadana, detailed below in Chapter 4. He also introduces elements found in the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] although not peculiar to it: the framing dialogue between Siva and Parvati and the creation of a Maya Sita before the kidnap. Indeed, illusion appears often as a matrix for phenomena, as in the Adhyatma Ramayana[*] .[34] ç There are again affinities with Bengali Rama stories, as well as with south Indian vernacular versions.[35] ç At the same time, events are consistently localized in Orissa; thus Rama's return to Ayodhya becomes the Bahuda[*] Jatra, or return of Lord Jagannatha's cart procession in Puri. Some events are given amusing human twists: on Mount Malyavan Rama gets a crane to supply him with food cooked by Sita, overcoming the bird's reluctance to accept food from a mere woman by assuring it that wife and husband are one.[36] ç At the same time, Balarama[*] Dasa must be credited with some originality. For example, the distinctively Oriya story of the origin of mushrooms in the umbrellas severed from Ravana's[*] chariot appears for the first time in writing in the Jagamohana Ramayana[*] .[37] ç On the whole this text weaves a wealth of novel detail around the framework of Valmiki. Its central place in the Orissan religious tradition is shown by its being read orally in toto, as Tulsi Das is used elsewhere in north India during the festival Dashahra.

Balarama[*] Dasa dealt with the story of Rama in a number of other, shorter poems of the forms known as chautisa (thirty-four couplets beginning with each letter of the alphabet in sequence) and barahmasa (with twelve verses for the months). These seem particularly to draw upon the Sundara Kanda[*] and the grief of the separated couple.[38] No illustrated copies of those works are known.

Two unpublished minor works are worth mentioning here because they have been illustrated at least once. These are a Durga Stuti and a Hanumana Stuti ascribed to Balarama[*] Dasa, known from an illustrated manuscript now in Ahmedabad.[39] Such stutis form a large class of popular verses in praise of various gods and goddesses. Several addressed to Durga are attributed to Hina (inferior) Balarama[*] ; although they follow the same meter as the Jagamohana Ramayana[*] , they are probably not the work of the sixteenth-century poet. The Ahmedabad illustrated text describes the occasion when Rama and Laksmana[*] were bound by Indrajita's snake-arrow. The hero recites his previous story to Durga, who advises him to pray to Garuda[*] , who in turn comes and disperses the snakes. The following part of the same work is devoted to Hanumana.

Later Oriya Texts

Oriya literature since 1550 includes many versions of the Ramayana[*] . There are, for example, several short works called Tika[*] Ramayana[*] , each purporting to be a précis of Balarama[*] Dasa, in fact also adding new stories.[40] The Vilanka Ramayana[*] of Siddhesvara Dasa is probably a work of the seventeenth century, concerning an interlude between the Yuddha and Uttara Kandas[*] in which a thousand-headed

Ravana[*] was killed with the intervention of Sita in the battle.[41] The eighteenth-century Angada Padi[*] of Vipra Laksmidhar[*] Dasa focuses on Angada's embassy to Ravana[*] .[42] ç Such short versions, like the ephemeral pamphlets summarizing the epic that are sold today, must have been widely known.

Yet it was the complex writing of Orissa's great poet, Upendra Bhañja, that was more frequently illustrated. Upendra was a member of the royal family of Ghumsar in central Orissa, today on the western edge of Ganjam District.[43] His grandfather, the Raja Dhananjaya[*] , had in the seventeenth century written a euphuistic poem called Raghunatha Vilasa[*] , in which Rama is identified with Jagannatha.[44] ç Upendra may have been born around 1670 and presumably lived in the world of the court, although his father ruled only briefly.[45] ç He himself mentions his initiation into the Rama Taraka Mantra, a spell invoking the protection of Rama, which accords with his frequent use of the Rama story in his poetry. His seventy poetic works, many of them long, belong mainly to the early eighteenth century.

Upendra Bhañja's writing in general can hardly be described with neutrality One touchy issue is his frequent use of erotic subject matter, which must have been widely acceptable in Orissan society at some points, although it has at times been condemned as obscene. A second sticking point is his elaborate style, which carries that of his grandfather many stages further. His word choice is arcane and Sanskritic, although the proximity of Oriya to Sanskrit makes his diction less artificial than it might seem. He employs the gamut of literary devices known to courtly poetry, or kavya: slesa[*] (punning), yamaka (alliteration), gomutra (zigzag reading), and many more. Such devices would seem to make for such obscurity that one might expect his work to have been known only in very limited circles. Yet his verses have long been used in the storytelling tradition called pala, where the verbal ingenuity, romance, and music of his lines still captivate rural audiences. As the great Oriya freedom fighter Gopabandhu wrote in this century,

Oh Upendra, the Pandits recite your lines at courts,

Gay travellers on the road,

The peasants in the, fields and ladies in the harems,

And the courtesans too, while they dance.[46]

The Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] or "Sport of the Husband of Sita," is a prime example of Upendra's poetic dexterity, Each line in the: work begins with the letter Va. Each canto differs from the next in the poetic device it employs, so that the effect is varied in sound as well as in substance. One canto may consist of relatively straightforward descriptive couplets, while: the next is long complexly rhymed verses based on double entendres. Nor does the selection of subjects inevitably emphasize the erotic, or sringara[*] mood. Valmiki's first six books (the Uttara Kanda[*] is omitted altogether by Upendra) correspond to the following cantos of the Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] :

Bala Kanda[*] : Chhandas 1-16

Ayodhya Kanda[*] : Chhanda 17

Aranya[*] Kanda[*] : Chhandas 18-26

Kiskindha[*] Kanda[*] : Chhandas 27-33

Sundara Kanda[*] : Chhandas 34-39

Yuddha Kanda[*] : Chhandas 40-52

The brief treatment of the critical events of the Ayodhya Kanda[*] shows a distinct preference for the lyrical over the dramatic.

The Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] refers respectfully to its own predecessors:

Valmiki and Vyasa each wrote Rama's epic.

Hanumana, the wind's son, wrote the play Mahanatak[*] .

Bhoja wrote Champu : Kalidasa's was perfected.

Balarama[*] Dasa wrote Oriya. On all I've reflected,

Bemused by these masterworks, with great trepidation.

There are stars in the sky for illumination,

Yet in the dark, fireflies also glow.

Please therefore accept my humble verses below.

(1.4)

In fact Upendra departs from Valmiki, following Balarama[*] Dasa in matters such as the creation of Maya Sita and going further than his Oriya predecessors in the inclusion of folk elements. He even alters the familiar structure by presenting Sita's birth before Rama's.

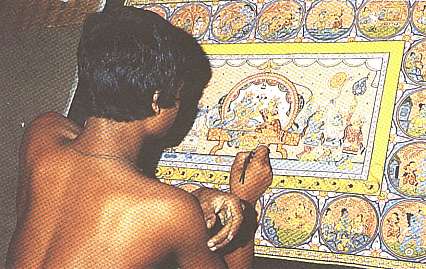

A second work by the same poet will enter into our study, although its main plot does not concern Rama at all. This is the Lavanyavati[*] , a romantic tale concerning the heroine for whom it is named and the hero Chandrabhanu.[47] Originally a heavenly couple, they are reborn as a princess of Simhala and a prince of Karnataka, who falls in love with her portrait. They meet in a dream, exchange love letters, meet secretly at the temple of Rameshvaram, and are married with their parents' consent. When Chandrabhanu departs to quell a rebellion, the couple live in romantic separation, but they are eventually reunited and ascend to the throne of Karnataka.

During preparations for the wedding, Lavanyavati's[*] father commissions a traveling entertainer to perform the Ramayana[*] in order to arouse her desire for Chandrabhanu.[48] As the translation of this portion in my Appendix 3 shows, the events of the epic are summarized succinctly in the text, generally following Upendra Bhañja's own Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] . At the conclusion, however, we realize that Lavanyavati[*] has identified Rama with her own beloved, and hence she presumably thinks of herself as Sita, the kidnap prefiguring her separation from Chandrabhanu. The adaptation of the Ramayana[*] in particular to the needs of romance may have to do with Upendra's own predilection for this divinity, apparent elsewhere in his work. In the Lavanyavati[*] itself, Rama is invoked at the very beginning. It is also appropriate, in view of the role of maya in versions of the Ramayana[*] popular in Orissa, that the whole tale should be presented as an illusion within a plot where dream and magic play a recurrent role.

Among other recent authors, Visvanatha Khuntia[*] is worth mentioning, not because he was directly illustrated but because his version of the Rama story was second only to Balarama[*] Dasa's in popularity. His name indicates that he belonged to a brahman family of temple servants in Puri. Khuntia[*] probably wrote early in the eighteenth century, and he was aware of Upendra Bhañja's works but primarily followed Valmiki.[49]

Visvanatha Khuntia's[*] work: is titled Vichitra Ramayana[*] , vichitra meaning "varied in melody," for the work is broken into sections to be sung to different ragas. It is also called a Ramalila[*] , suggesting its use as a dance-drama, and indeed it is not only read as a text but also used by boy dancers (Gotipuas[*] ) and is beloved for its simple lyrical poetry This version of the: story follows the southern recension of Valmiki, rather than the eastern (as did Balarama[*] Dasa's) and is on the whole closer to the Sanskrit plot than to Sarala Dasa's Mahabharata or even Upendra BhaÖja's Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] .

Visvanatha Khuntia's[*]Vichitra Ramayana[*] , perhaps because of its popularity, has played host to interpolations, which do not appear in older manuscripts of this text.[50] The episode of Mahiravana[*] is an interesting one, actually attributed in the printed text to Vikrama Narendra, a nineteenth-century author of his own, separate, Ramalila[*] This story, widespread in Sanskrit and in Indian vernaculars although not in most Oriya texts, involves an additional demon invoked by Ravana[*] after the death of his son Indrajita. Hanumana forms a fortress of his extended tail to protect the heroes but is tricked into letting Mahiravana[*] enter and abduct them. Mahiravana[*] prepares to sacrifice them to a form of the Goddess, but Rama asks the demon to demonstrate how to bow before her, at which point the Goddess decapitates him. The Sakta twist to the story, which is to be expected in Bengal, must also have appealed to elements in the populace of Orissa.

Performances

The value of the fact that various oral traditions remain alive in Orissa is inestimable for the art historian usually forced to work from written texts alone. But I am also acutely aware of the difficulty of conveying ephemeral, constantly varying, and multidimensional versions of stories. Hence the impassioned but unsystematic nature of my account. I shall not pretend to do justice to the rich performing arts of Orissa per se.

Popular Enactments: Ramalila[*] , Danda Jatra, Sahi Jatra

Ramalila[*] ("Geste of Rama"[51] ) is a widespread type of popular performance. The genre encompasses various dramatic enactments of the story of Rama by nonprofessional actors, men playing women's roles, common throughout north India, ranging in duration from ten to thirty-one nights, concluding on the autumn holiday Dashahra. In eastern India, however, Dashahra is fundamentally associated with some form of the. Goddess. In Orissa in particular, Ramalila[*] is performed during the two weeks following Rama's birthday, Ramanavami, in March or April,[52] ç a time that makes sense for an enactment that begins with Rama's birthday, on Ramanavami. This timing within the agricultural cycle makes the performance a celebration of the spring harvest. And it is pleasant at the beginning of intense summer heat for villagers to enjoy the cool night hours with performances, generally from midnight till dawn, while actors and audience are free to sleep in the daytime.

Another difference between these Ramalilas[*] and those of north India, which are generally based upon the Ramcharitmanas of Tulsi Das, is the use of many

different versions of the story in Orissa. I contend that the experience of viewing village performances of Ramalila[*] , vivid from childhood memory and from annual repetition, at times had more impact upon artists than did normative written texts. Yet the very diversity of Oriya Ramalilas[*] urges one to be cautious in drawing a connection with particular modern survivals. At least we can be sure that there were some performances in the areas and at the times in which most of the illustrated Orissa Ramayanas[*] were made. My observations are weighted in favor of those places where I actually watched Ramalilas[*] in 1983 and 1990.

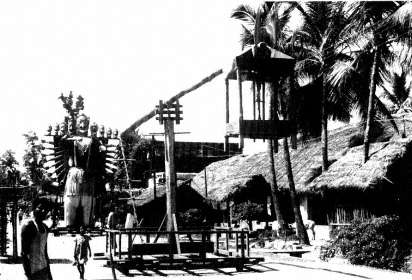

In both years, I spent much of the fortnight following Ramanavami in Dasapalla, a small town (c. 10,000 inhabitants) in the forested interior of Puri District, whose Ramalila[*] is locally considered the best dramatic spectacle. The text recited here and commonly referred to as "the Purana[*] " is a copy of the Ramalila[*] of Vikrama Narendra, a little-known early nineteenth-century author.[53] Local tradition traces the performances back to the reign of the ruler of Dasapalla state, Krishna Chandra Deo Bhanj (1805-45), who was also known for his pacification of the Khonds and other tribes in his kingdom. Narayana Deo Bhanj (1896-1913) sponsored particularly splendid performances and built (300 meters from his palace) the Mahavir Temple, where today most of the drama takes place.[54] ç Old people remember with nostalgia the days of royal support, when the queen loaned her own gold jewelry to the actors. After Indian independence the Temple Endowment Board took over supervision with remarkable effectiveness. There is widespread enthusiasm, both among local administrators and elders (such as the school teacher Brindaban Mohanty, who selflessly directs performances these days) and among the actors. People tell of a former actor, who as an old man lost his voice but who insisted on playing his role while others spoke the lines. A similar spirit is still alive among many local youths today. The reputation of Dasapalla is also due to its spectacular props, a 25-foot crane that serves as Puspaka[*] Vimana and a 30-foot image of Ravana[*] , burned on the final night (Figure 41). Each year old wooden masks of cunning design are vividly repainted—Surpanakha's[*] with a removable nose. Most have slits beneath the painted eyes, enabling the actor to see, while the eyes of the mask itself are more emphatic than they would be if cut out. Electric lights are used lavishly today, both to decorate the town for the festival and, ingeniously, as part of the performance. For example the three lines drawn by Laksmana[*] on the ground in front of Sita's hut consist of strings of tiny bulbs that suddenly glow, highlighting the protective boundary.[55] ç

Among other Ramalilas[*] , Bisipada, a smaller town (c. 3,000 inhabitants) 10 kilometers southeast of Phulbani, struck me as most traditional in 1983, although in 1990 it had lost some of its vitality. Here a palm-leaf text is in use, composed by Janardana Dasa at least a century and a half ago.[56] Bisipada was never a royal center, and the performance there was in the past, as it is today, organized by the village elders, largely Bisois (soldiers, of the khandayat caste), who gave their name to the town. Props survive in older form than those of Dasapalla, including a fine appliqué canopy that goes back to the nineteenth century.[57] ç The masks have not recently been repainted. The ambitious props of Dasapalla are absent here, but wooden torsos encase the bodies of the actors who play the three major demons, so that the heads rise to a height of nine feet. The acting style in 1983 was strikingly traditional, with long passages in which the royal characters simply moved

Figure 41.

Dasapalla Ramalila[*] . Ravana[*] and Puspaka[*] Vimana.

their feet back and forth in a stylized step. In 1990 the Bisipada performance showed more of the strutting and exaggerated gestures associated with Jatra (professional theater). In any case, it would be wrong to present any center as authoritative, for diversity must always have existed. Diverse acting styles, reflecting the alternatives of conservatism and innovation, may well have competed in the past.

Ramalilas[*] flourish along the Mahanadi, as far as Baudh and reportedly Sambalpur. Gania follows a copy of Vikrama Narendra's text, which was adopted from Dasapalla, 20 kilometers to the southwest. Yet details of staging differ from those of Dasapalla: few masks are used, and a cart wheel turned on its side serves as Puspaka[*] Vimana, with Ravana[*] and the kidnapped Sita seated on top, its whirling suggestive of movement through the air. Nearby Belpada follows the printed text of Vaisya Sadasiva, an eighteenth-century work widely known in other parts of Orissa and itself directly influential for one of Orissa's greatest living painters.[58] Here an elaborate two-story stage is used, quite different from the simple canopied spaces that generally house the core of action near a shrine, with some processional movement along the streets of other towns.[59] ç

To the south, other theatrical genres present the story of Rama, including the Desia Nata[*] of Khoraput District and the professional Jatra, which remains popular throughout Orissa. But to return to the more participatory and ritually based Ramalila[*] , we have every reason to think that it flourished in Ganjam District and those areas near Puri where most of the images to be considered were produced. Thus near Khurda a Ramalila[*] continues to occur at a slightly later ritual date.[60] Manibandho, near Kavisuryanagar, is reported to maintain a Ramalila[*] with masks

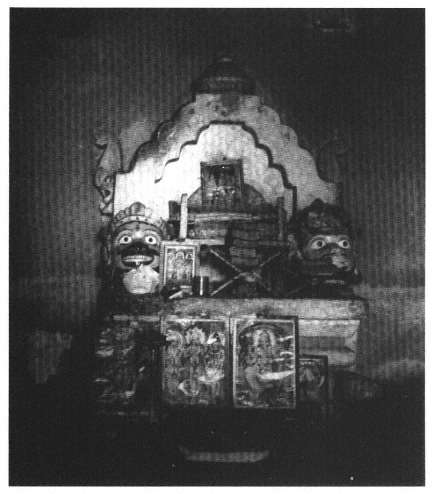

today.[61] In Chikiti, far to the south, the ruler Krishna Chandra Rajendra (1750-80) composed a Ramalila[*] of which one illustrated palm-leaf manuscript survives.[62] ç There, lively performances with masks took place during the fortnight after Ramanavami until 1956, when they ceased for lack of royal support.[63] ç And in Amrapura, near the large Rama temple of Odagaon, the masks of a now defunct Ramalila[*] tradition are preserved, those of Hanumana and Añgada still in worship on the altar of a temple (Figure 42).[64] ç Thus it is likely that palm-leaf illustrators and painters in the nineteenth century knew performances broadly analogous to those of Dasapalla and Bisipada.

Amid this welter of local forms, what generalizations can we make about plot structure? In Dasapalla alone, the number of daily performances has varied from ten to sixteen during the past fourteen years.[65] Moreover, the exact division of

Figure 42.

Amrapura. Ramalila[*] masks and palm-leaf manuscripts in worship in

Mahavir Temple.

events on particular nights may vary from year to year.[66] The following schedule of Dasapalla in 1990 provides one sample:

1. Dasaratha's sacrifice, Rama's birth

2. Protection of Visvamitra's sacrifice (Tadaki[*] killed, Ahalya freed)

3. Breaking the bow

4. Rama's marriage and the meeting with Parasurama

5. Killing the rhino

6. Rama's exile (and Bharata's visit[67] )

7. Killing Virayudha (and Rama's visit to Puri and to various sages)

8. Kidnap of Sita[68] ç

9. Rama's grief

10.Killing Valin

11.First attack on the fort and finding of Sita

12.Second attack on the fort and death of Kumbhakarna[*]

13.Burning of Lanka[*] and death of Ravana[*]

14.Coronation of Rama

Either the fourth or the fifth night has consistently been devoted to killing the rhino, an event that may come as a surprise in view of the Rama story as a whole. The action, corresponding to only three pages of Vikrama Narendra's text, took over three hours to perform in both 1983 and 1990. Dasaratha requires meat to perform the sraddha sacrifice for his ancestors. The four brothers lead the audience in procession to a market several kilometers' distance from the stage, accompanied by the deep, pulsating beat of kettle drums, a tribal instrument as opposed to the oblong mridanga[*] that accompanies the normal chanting. Sabaras dance and a Sabara king comes to help in the hunt (Figure 43), when ultimately Rama shoots a rhino, symbolized by a green coconut. The people of Dasapalla consider this event distinctive of their Ramalila[*] .[69] This is the most gratuitous case of emphasis upon tribal elements in the performance, although tribal references occur at other points as well—the Sabara king (Guha) who helps the exiles cross a river, and the Sabari woman who offers Rama a mango that she has tasted to be sure it is ripe. Historically these themes may reflect Krishna Chandra Deo Bhanj's effort to pacify the Khonds in Dasapalla; at the same time, their retention is made possible by the general visibility of these aboriginals living on the periphery of Hindu culture in central and western Orissa.

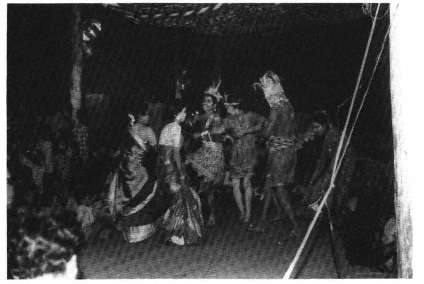

The interpretation of particular events often differs from town to town. For example, in Bisipada, Siva's bow is brought in a ponderous wood chest, an occasion for extended acrobatics by Janaka's servants, preserving the gymnastic traditions of this soldier village. In Dasapalla the bow glides quickly onstage in the same sari-covered frame that had served as a boat the night before, whereas the entry of Sita's suitors is humorously prolonged—including a mincing Napumsaka (eunuch), a foul Mleccha (foreigner with a broom as tail), and several other suitors Who arrive on motorbike. The overall sequence is similar in the two towns, except that in Bisipada the first eleven events are extended over more time. Thus the

Figure 43.

Dasapalla Ramalila[*] . Sabaras dancing.

burning of Lanka[*] by Hanumana occurs on the climactic penultimate day, followed by all the events of the Yuddha Kanda[*] , squeezed into the last night. This truncated version of the story emphasizes Hanumana's exploits in a way we shall occasionally encounter in palm-leaf illustrations.

All of the Oriya Ramalilas[*] have a homey flavor by comparison with the more widely known pageant of Ramnagar, still supported by the Maharaja of Banaras.[70] This quality follows in part from their scale: at the major pilgrimage center Banaras it is possible to assemble a crowd of 500,000, whereas at Dasapalla the audience comes from villages in the vicinity and is closer to 5,000. This in fact is as much as the town spaces can accommodate, creating a sense of bursting popular interest, a wall of spectators whose eager faces extend into the surrounding darkness. The relative intimacy of the rural setting enhances audience participation in the enactment itself, whereas the great crowds of Ramnagar move as devotees of the divine characters. In Orissa the actors are familiar townsmen. Women of the village join in Rama's wedding, ululating as they would at an actual celebration.

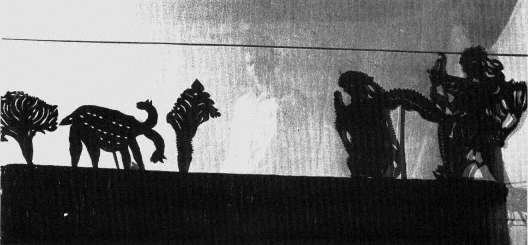

The night of Sita's kidnap at Dasapalla illustrates many compelling dramatic effects. Surpanakha[*] appears first as a seriously seductive woman, played by one of the most accomplished young actors, then as a comic masked demon, denosed, who brings in a lively band of other demons. Ravana[*] in royal form without a mask (acted by a magisterial member of the old royal family) approaches the sympathetic sage Maricha, and a small wooden deer with two heads is pulled onstage (Figure 44). Suddenly at 3 A.M. thousands of spectators troop up the road from the primary stage near the temple to an area specifically identified as Mount Chitrakuta[*] , where the acting space is a narrow passageway in the middle of the seated audience. At one end sits Sita, joined by Maya Sita in ghostly form behind a translucent

sari that forms the wall of the hut, as Rama departs into the night pursuing the little wooden deer.[71] Laksmana[*] leaves and a mendicant appears, the illusionary form of Ravana[*] who drags away Maya Sita at 4:15 A.M. Now the audience again moves a hundred meters to the crane, where the royal form of Ravana[*] , Maya Sita, and the chief singer revolve in the air, propelled by fifteen youths who weight the opposite end of the huge fulcrum. Jatayu[*] fights in vain, and Maya Sita drops her ornaments to a happy band of monkeys, just as dawn comes up behind the huge effigy of Ravana[*] that had been raised with great effort the previous evening.[72] ç It is hard for the remaining audience not to feel both awe at the ominously whirling crane and a sense of identification with the optimistic monkeys who chatter away at its own level as another day begins.

Danda[*] Jatra is categorized as a separate genre, although in fact it might be regarded as a special form of Ramalila[*] , for it takes place at night at the same time of year, the fortnight after Ramanavami. As far as 1 know, the name is peculiar to Asureshvar, a town about 20 kilometers from Kendrapara, just north of the river Mahanadi.[73]Danda[*] means "road," referring to the main street of the town, where the action originates at the Raghunatha Temple and proceeds to the Jagannatha shrine at the opposite end. The heroes are carried down the road on the shoulders of devotees and given offerings along the way, with some analogy to the great cart festival of Orissa as well as to the tradition of static tableaux, or jhanki[*] , found

Figure 44.

Dasapalla Ramalila[*] . Magic deer.

Figure 45.

Puri. Sahi Jatra. Mahiravana[*] .

throughout north India.[74] The Ramcharitmanas of Tulsi Das is read in Oriya translation both day and night throughout the fortnight. The Raghunatha Temple and the entire observance were founded by Rama Krisna[*] Dasa, a local landowner, several centuries ago.

What makes the Asureshvar event distinctive is that townsmen desiring some goal may undertake a vow, or vrata, at this time. To do this entails assuming the

guise of a monkey, for Hanumana is the epitome of devotion. The believer rents a monkey costume from the temple, consisting of a wooden mask, leathered tail, and chain of bells (Plate 1). He eats only once a day, chants the name of Rama, performs simian antics, and begs for alms during the period of the vow, which may last for a week.[75] In short, here yet more ordinary people participate in the Ramayana[*] story, The role of the vanaras (forest animals) is made vivid, with monkey-men appearing in the bazaar and running around the town.

Sahi Jatra may represent another variant upon the Orissan Ramalila[*] . This term, peculiar to Puri, designates performances put on by the sahis, or districts, of the town, which are not restricted to Ramanavami, although a major cycle occurs in the fortnight following that day.[76] The episodes selected are not those of rural Ramalilas[*] . They tend toward tableaux focused on a few characters. The same episode may be performed by different streets of Purl, with a sense of neighborhood competition, although on some nights the performance is left to one street or gymnasium (akhada[*] ) to organize.

Thus in 1983, the Sahi Jatra for Ramanavami began between nine and ten P.M. with a simple procession of the four brothers as boys, together with Risyasringa[*] , wearing two horns (Plate 2). The second night was devoted to acrobatic performances by various demons. The first two, most popular, were called Naka and Kana, "Nose" and "Ear," possibly a reference to the two organs of Surpanakha[*] that Laksmana[*] was to out off. While that action was not performed, spectators kept quoting a famous double entendre from the Vaidehisa Vilasa[*] of Upendra Bhañja, cited below in Chapter 4. On the third night three Durgas, played by particularly strong men, including a member of the painter community, danced on different streets for several hours, an arduous undertaking in view of their heavy masks and costumes involving multiple arms. There were also floats that bore impersonations of Ganesa[*] Narasimha, generic warriors (Nagas), as well as some characters specific to the Ramayana[*] , such as Ravana[*] . On the fourth and sixth nights no action occurred. On the fifth, seventh, and eighth nights the action revolved around various Ravanas[*] , which some spectators called Mayaravana[*] and Mahiravana[*] . These performers appeared late in the night, seemed almost to be in trance, and went on dancing into the daylight, pausing regularly to rest from the weight of their heavy costumes (Figure 45).

In short, this form, as our term "street theater" suggests, is impromptu and invites participation by the people of Puri. Narrative action is minimal, and references to the Ramayana[*] are haphazard. Nonetheless the dramatic image is memorable, particularly of great multiarmed characters dancing, drenched in sweat, the audience itself in a hallucinatory state.

Dance Traditions

Ramayana[*] themes appear throughout the gamut of Orissa's dance traditions. The Gotipua[*] boy dancers, as already mentioned, use Visvanatha Khuntia's[*] Vichitra Ramayana[*] , but their repertoire centers more on Krisna[*] . Likewise in the most classicized, or margi, dance form of the region, Odissi[*] the Ramayana[*] is present in a minor way, it being virtually impossible to distinguish long-standing local variants in the story used. Chhau, a more transitional form that includes folk or martial