Griffith's Film Acting

The little evidence available leads to the conclusion that most of the performers with whom Griffith worked used the histrionic code, as did Griffith himself, though Griffith, as an aspiring man of the theatre, must at least have attended verisimilarly coded performances. Eyewitness accounts and films provide evidence of Griffith's notions of appropriate cinematic acting in 1907 and 1908.[15]

After the failure of A Fool and a Girl , a financially desperate Griffith became involved for the first time with the film industry, selling story ideas, appearing as an extra, and even playing a few leads. Between December 1907 and July 1908, Griffith appeared in twenty-three films that we know of, twenty-one at Biograph and two, Rescued from an Eagle's Nest and Cupid's Pranks , for Edison.[16] Wallace McCutcheon, who directed Griffith in his Biograph films, summed up his actor's talents in two words: "He stinks!" McCutcheon continued to employ Griffith not for his thespian abilities, but because he had story ideas and suggested "bits of business for other performers."[17] Henry Marvin, Biograph's vice-president and general manager, also worried about the skills of Biograph's new acquisition. In his unpublished memoirs, Billy Bitzer discusses Griffith's first film appearances:

In the spring of 1908 when Mr. Griffith first got before the camera as an extra when my boss . . . Mr. H. N. Marvin . . . saw the picture . . . he could not help but notice that the character Mr. Griffith was playing, an innkeeper or bartender, in a picture with a "What Ho, what'll it be me Hearties" attitude accompanied with a swinging gesture of his arms . . . that the arms were a blur, looked more like fans than arms, for which I was blamed . . . It would take a shutter of a hundredth of a second to stop the waving arms and some of the other quick movements of . . .

Rescued from an Eagle's Nest: Griffith's

superfluous gesture.

Griffith. I figured the only thing to do would be to place this Griffith to the side of scenes and then if his gestures were wild, I could move the camera ever so slightly and he could do his waving out of the scene. [Griffith said later], "Why didn't you tell me to slow down. I thought action had to be exaggerated the way I had seen them do it in Vitagraph pictures."[18]

From this comment we can infer that in his initial appearances Griffith thought it necessary to adapt his stage acting style to the new medium, which he did by speeding up the fully extended, heavily stressed movements of the unchecked histrionic code.

Close analysis of Rescued from an Eagle's Nest (J. Searle Dawley, director, Edison Studios, 1908) and At the Crossroads of Life (Wallace McCutcheon, Jr., director, Biograph, 1908) reveals that it was not blurred arms that set Griffith apart from his fellow film performers but rather an intensely self-conscious theatricality combined with the making of narratively superfluous movements. In Rescued , Griffith plays a woodsman whose child is stolen by an eagle and carried to its nest. In the film's second shot, Griffith and two others cut down a tree. The situation makes histrionically coded gestures unnecessary: all the actors have to do is saw. But Griffith nonetheless pauses to gesture to his fellow workmen and then point at the tree, as if exhorting them to greater effort, though they seem to be working hard enough. In the sixth shot, Griffith and friends cut down another tree. After it falls, Griffith extends his left arm and swings it back and forth while smiling in what seems an entirely meaningless gesture contributing neither to story nor characterization. At this point, his wife rushes in and tells him about the kidnapping. She gestures upward, and he points upward three times in succession before leading the group offscreen with much arm-waving. Griffith and company chase the eagle until they reach the top of a cliff on the side of which the eagle resides. The men tie a rope around Griffith and lower him over the side. As he begins

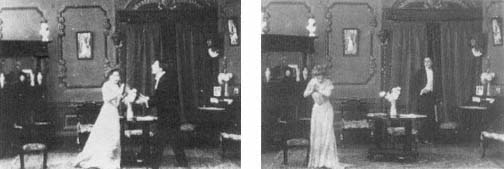

Left: At the Crossroads of Life: Griffith pleads with his beloved (Museum of Modern Art Film

Stills Archive).

Right: At the Crossroads of Life: Griffith as rejected suitor (Museum of Modern Art Film

Stills Archive).

his descent, and then again as he disappears, he raises his right hand in a wave, the gestures all but meaningless. After landing on the cliff ledge, Griffith kneels screen right over his stolen child and then, seeing the eagle, assumes an extremely theatrical posture. He looks around and extends his right arm fully before rising with both arms extended outward, right leg bearing his weight, knee slightly bent, and his left leg back, knee bent as if to kneel, then puts both hands to his head and holds the pose. Having killed the eagle, he kicks it over the cliff edge, accompanying the kick with a sweeping outward gesture of the right arm. As the eagle falls, he leans over and shakes his fist at it.

Griffith's excessive theatricality is even more apparent in At the Crossroads of Life , where at times he seems to be almost intentionally parodying the histrionic code. In his first scene in this film, he comes to visit his lover. As he enters through a curtained doorway, he looks right, then left toward the woman. He pauses to assume an "I love you" pose, both hands reaching out toward her. He advances toward her with hands still extended, takes her hands and kisses one, then holds her hand with his right hand while pointing toward the door with his left in a "come away with me" pose. He then takes both her hands in his again and leans in so that his face is next to hers. When a servant enters, they separate, Griffith holding his right hand extended sideways, the arm slightly bent, and the other hand near his chest, again striking an attitude. After the servant leaves, he kisses the woman again. She breaks away, but he keeps both arms extended toward her then drops his hands to his sides as he walks out. At the door he pauses again, points at her, talks, turns to leave, and clenches the hand that had been pointing, so that he exits with one arm extended backward and fist clenched. Later, at the denouement, the woman rejects him. He shakes hands with her, turning his head momentarily, then turns back thrusting his chin forward in a "noble" pose. He kisses her hand, steps

back, still holding her hand and looking at her, and, turning away from her, he brings his hand up to his chest and then down again in a conventional gesture of rejection.

These two films illuminate Marshall Neilan's comment about Griffith's acting. It was not simply that Griffith used the histrionic code, it was that he used it inadequately. Judging both by his fellow performers in these films and by other films featuring histrionically coded performances, Griffith was a bad actor by the standards of the histrionic code. He took the self-consciousness and theatricality inherent in histrionically coded acting and exaggerated it, giving each gesture and pose a great and unnecessary emphasis.