Painting Under the Shadow:

California Modernism and the Second World War

Susan Landauer

The Scenario of Chaos

Modernism, as Malcolm Bradbury and James McFarlane tell us, is born of "cataclysmic upheavals of culture, those fundamental convulsions of the creative human spirit. . . . It is the one [artistic impulse] that responds to the scenario of our chaos."[1] Behind these words is an understanding that war is among the defining themes of modernism in Europe and America. Despite Virginia Woolf's oft-quoted line about the world changing in 1910, it was the First World War that proved such a great catalyst for modernism across the arts. The explosion of modernism—whether the dada performances in Zurich, the poetry of T. S. Eliot, the drawings of George Grosz, or the plays of Bertolt Brecht—was clearly a response to the war, even when artists abandoned the themes of battle and violence for those related to social structure or the human psyche. Perhaps because of the immense jolt of the First World War, the modernist burst after World War II was less intense than that of the teens and twenties. But this second surge of modernism was indeed significant, bringing us the introspection of French existentialism, the nightmare visions of Francis Bacon, and the absurdist plays of Samuel Beckett.

In California, however, the sequence of events was reversed. In contrast to the European capitals or New York, the modernist explosion after the Second World War was far more extensive than that following the First. As the essays in this volume attest, there were pockets of modernist activity in California well before the 1940s. But the number of modernists was small by comparison to that in New York, where precision-ism dominated the artistic discourse of the 1920s and where abstractionists such as Stuart Davis could thrive even during the aesthetically conservative 1930s. For California, it took World War II to initiate the first great burst of modernism. The catalyst was not only the horror of the war, but also the explosive transformation of the state. More than half of all army cargo and troops bound for the Pacific theater passed through San Francisco's Golden "Victory" Gate.[2] In the space of a few years, several million people moved to the West Coast to work in the country's largest centers of shipbuilding

and aircraft construction—mostly in and around San Francisco and Los Angeles. By the late 1940s the San Francisco Chronicle was boasting that the massive westward migration "dwarfs the crusades and makes the Gold Rush seem like a boy scout outing."[3]

Mirroring these sweeping demographic changes, California's artistic community grew as the war brought artists—returning veterans—from all parts of the country, many arriving through the ports of Los Angeles and San Francisco. In addition, with the influx of refugees from fascism came European avant-garde ideas. Although New York was the center for European artists in exile during the war, Los Angeles drew a sizable number of artists, writers, musicians, and composers, including Thomas Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Arnold Schoenberg, Salvador Dalí, Man Ray, and Igor Stravinsky.[4] San Francisco attracted fewer émigrés than Los Angeles, but artists such as Stanley William Hayter, Gordon Onslow-Ford, Wolfgang Paalen, Jean Varda, and Max Beckmann—and returning expatriates like Charles Howard and Henry Miller—helped to expand the cultural horizons of the state.

Also adding to California's newfound cosmopolitanism was the wartime museum policy of circulating exhibitions of contemporary painting from coast to coast—initi-ated in part to offset the removal of art treasures inland for safekeeping. The director of the San Francisco Museum of Art, Grace McCann Morley, embraced the policy enthusiastically. Morley's exhibitions, many of them loan shows from the Museum of Modern Art in New York, brought to Bay Area audiences the latest work of Max Ernst, Roberto Matta, André Masson, Yves Tanguy, Pier Mondrian, and many other European émigrés then in New York. Indeed, the first major survey to include contemporary painting by European refugees in America, Abstract and Surrealist Art in the United States , was organized by Morley with the help of the New York art dealer Sidney Janis in 1944 for travel on the West Coast. The exhibition featured, among others, the little-known painters Mark Rothko, Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, and Jackson Pollock.

The impact of all this activity was immediate and profound. By the end of the war, California artists found themselves at work in national and international contexts that pulled them out of their provincial preoccupations and toward broader worldviews. Although in 1939 the critic Alfred Frankenstein observed a nearly exclusive focus on "the more or less objective recording of native themes and situations,"[5] by the war's close in 1945 the Montgomery Street Skylight was reporting "a mass conversion to abstraction," even among "veterans of the picturesque flowerpot."[6] The forms California modernism took reflected more or less those found elsewhere in the country: surrealism, abstraction, and expressionism, fusing toward the end of the forties in the movement known variously in San Francisco as "free-form," "first sensation," and, in less sympathetic quarters, the "drip and drool school." Abstract expressionism was slower to attract adherents in Southern California. While San Francisco's most forceful presence was Clyfford Still, Los Angeles's modernism was dominated by the hard-edge abstraction of Lorser Feitelson and John McLaughlin and the tempestuous figuration of Rico Lebrun.

As different as their aesthetics may have been, these artists shared a double-hermed response to the war. On the one hand, their embrace of modernism was itself a turning outward, a manifestation of a new global perspective that deemed regionalism irrelevant. Modernism, as the cultural lingua franca of the free world, represented a repudiation of totalitarianism and its brutal curtailment of artistic expression. At the same time, this modernism—and herein lies its most significant departure from the machine aesthetic of much post-World War I art in America—was deeply inner-directed. Expressionists, surrealists, and abstractionists alike responded to the ferment by turning inward, away from social and political reality, to the realm of individual imagination. It is in part an index of their revulsion from the mass destruction made possible by modern industry and technology that so many modernists in California, like their counterparts elsewhere in the country, concentrated on such un-modern phenomena as dreams, myth, and magic. The depth and breadth of this primitivist impulse can be measured by its grip on such relatively conservative painters as Matthew Barnes. The tendency cut across political and aesthetic lines.

Despite such pervasive subjectivism, many California modernists wanted to contribute to the war effort. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) Southern California Art Project, until it closed in 1942., hired artists to paint murals for troops in training—to produce "fighting art to inspire fighting soldiers," in the words of Feitelson, the project's design supervisor.[7] Most modernists, however, drew the line at creating propaganda for the Office of War Information (despite tempting offers of employment), letting more traditional artists and Hollywood filmmakers take on the work of boosting homefront morale. Their view conformed with Duncan Phillips's in his classic mandarin exhortation not to press art into the service of any social, political, or religious idea, since "art is a social communication and a national asset, but never more so than when it is a miracle of personal expression."[8]

The majority of California modernists were thus content to express their subjective responses rather than comment overtly on the conflict. Most registered the impact of the war through dramatic changes in the content or style of their work. There is little in the San Francisco Museum of Art's painting and sculpture annual of 1941 to suggest that a global conflagration was taking place. A year later, however, Robert Howard and Adaline Kent were alluding to the war through titles such as Combat and Victory . Palettes also darkened to suggest a gloomy despondency. Artists of various aesthetic persuasions, from Ruth Armer to Hans Burkhardt, expressed the prevailing atmosphere of dread by painting in deep reds and blacks. This color combination, a favorite of Still's, became a mainstay for Bay Area abstract expressionists well into the 1950s.

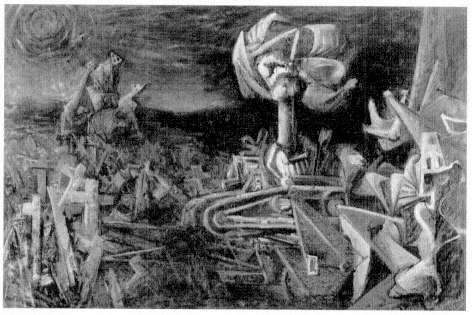

Another, more familiar, modernist strategy for expressing the mood of the period was through compositional fragmentation. This approach can be found in the twisted automobile carcasses of Howard Warshaw (Fig. 14), the decomposing anatomies of Lebrun, and the colliding razor-edged shards of Feitelson, each expressing the flux, instability, and dislocation of the period.

Figure 14

Howard Warshaw, Wrecked Automobiles , 1949. Gouache on canvas, 23 × 47 in.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles County Funds.

At the other extreme, but just as much a response to the upheaval, were the meticulously controlled abstractions of James McCray, Frederick Hammersley, and Peter Krasnow. Krasnow's work in particular demonstrates what Austin Warren called the "rage for order," the urge to impose some measure of control on a chaotic world (see Plate 4).[9] Krasnow's perfectly axial bricks of radiant color were intended as a soothing balm in turbulent times: "When tragedy was at the deepest point," he later said, "my paintings breathed joy and light—color structure instead of battle scenes, symmetry to repair broken worlds."[10]

The painting of John McLaughlin presents an interesting bridge between these opposing strategies for dealing with the trauma of the war and its aftermath. While at first glance the neat contours and streamlined surfaces of McLaughlin's geometric abstractions communicate a universe of order and stability, their ambiguous spatial relationships effectively undermine the initial impression of harmony. Although Susan Larsen's interpretation of McLaughlin's abstractions as profoundly anticlassical may be an overstatement, these works do provide a subtle commentary on the psychological climate of the era.[11]

Most California modernists approached the theme of war iconographically rather than through such oblique indices of style. Following Rufino Tamayo's lead, they depicted beasts locked in battle to convey the savagery of military aggression or, like Ernst painted ruins crumbling under relentless vegetation to suggest civilization's moral decay

It is interesting to see how closely realists and abstractionists converged thematically during the 1940s. Both were consumed with allegories of strife and despair, differing primarily in their degree of literalism.

Amid the passion and suffering of the war, it is not surprising that the crucifix became a common metaphor, treated by figurative and abstract painters alike. Lebrun's ambitious Crucifix cycle (1947- 50), comprising over two hundred drawings and a large triptych, is perhaps the best-known example, but Burkhardt and Eugene Berman also treated the subject. Their paintings are among the few modernist attempts to bestow a measure of nobility on those who fought and suffered in the war. As an emblem of the soldier's heroic sacrifice, the crucifix had been invoked in the war poetry of Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, and Randall Jarrell. The historian Paul Fussell has traced the image to the trenches of World War I, where rumors circulated about Germans' crucifying captured soldiers, rumors the press sensationalized to rally public support for the war. A crucifix incident at the front lines during World War II also made its way into American newspapers—testimony to the power of the image.[12] As general a part of the culture as the crucifix is, Frank Lobdell's later ascending spread-eagles—which also suggest the Resurrection—probably had their source in the wartime adoption of religious allegory.

Although modernists in California expressed their emotional reactions to the war, and in some cases dealt with the moral, psychological, and physical costs of the conflict, the indirection and nonspecificity of their work generally took the political bite out of it. The Second World War provoked few overt protests or attacks on society, and certainly nothing as combative as the angry denunciations of the dadaists or the Weimar expressionists. Curiously, one of the most scathing condemnations of World War II came not from the liberal modernist quarter, as one might expect, but from the conservative Midwest regionalist Thomas Hart Benton.[13] Benton's murals of burning farms and soldiers blown to pieces stirred up far more controversy than such noncommittal paintings as Charles Howard's First War Winter (1939-40). Howard's painting carries no more political freight than a December rainstorm by the realist Millard Sheets. Not until the mid-1950s, with the rise of Bay Area funk art, would California modernists in significant numbers become conspicuously political in their art.

In fact there was little clear-cut opposition to the war among modernists anywhere in the country until after it had ended and the mind-bending human toll from the death camps and atomic explosions was tabulated. Although the overwhelming majority of modernists in California harbored pacifist sentiments, most believed, like the American population as a whole, in the necessity of U.S. involvement in this particular war. Such support did not dampen the agony and horror so many California modernists incorporated into their art. But the war engendered greatly varied artistic expressions, from the highly aestheticized anger of Burkhardt to the whimsical escapism of Clay Spohn's War Machines and the ominous impastoed canvases of many San Francisco abstract expressionists.

Disarming Parables: Hans Burkhardt's War Paintings

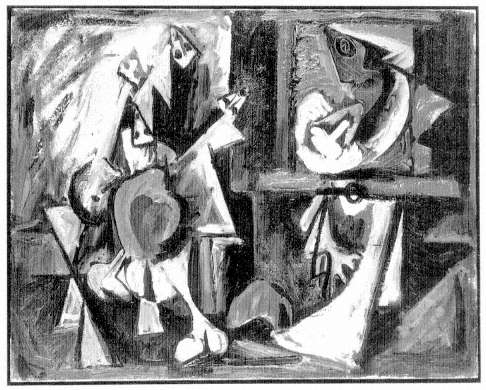

Hans Burkhardt stands apart among modernists in California, not only for his opposition to World War II at its very outset, but also for his willingness to confront political reality directly in his art. Burkhardt's more than forty antiwar paintings, begun several years before America entered the conflict, were virtually the only modernist protests in California. Paintings such as One Way Road (1945), with its imagery of limitless, incalculable destruction, or Iwo Jima (1945), with its bloody mutilation, contrasted dramatically with the popular media's sanitized portrayal of the war in the 1940s, when even novelists were admonished not to write of combat as an unpleasant affair.[14] Burkhardt's works were intended to jolt viewers out of their apathy, and indeed, they sometimes provoked heated reactions. Even his War, Agony in Death (1939-40; Fig. 15), which condemned the German bombing of the Basque town of Guernica, inflamed Los Angeles viewers in 1944. One woman attacked it with a cane and had to be forcibly removed from a gallery on Sunset Boulevard.

Burkhardt spent the late 1920s and 1930s receiving private tutorials from Arshile Gorky in New York, where, along with Gorky's other informal pupil, Willem de Kooning, he developed a relatively sophisticated understanding of French abstraction from Cézanne to Miró. Burkhardt's thematic concerns, however, soon diverged from those of de Kooning and Gorky, both of whom kept their distance from the political arena. As early as 1937, after Burkhardt had moved to Los Angeles, his work began to reflect the growing turmoil in Europe. In 1938 he initiated a series of canvases on the theme of the Spanish Civil War, culminating in War, Agony in Death , the first of his mural-sized antiwar paintings. Burkhardt claimed to have been unaware of Picasso's Guernica , and indeed, the final product synthesizes expressionist and surrealist styles in a very un-Picasso-like manner, with slashing brushwork and a palette of lurid reds reminiscent of Chaim Soutine's. Unlike Picasso, Burkhardt does not attempt to evoke the actual bombardment but presents a generalized image of devastation. Although the painting is dominated by a back-thrust head with mouth open wide that recalls Picasso's shrieking figures as well as such earlier antecedents as Hieronymus Bosch's gaping jaws of hell, Burkhardt's head is less easily identified. Half-human, half-armored tank, its twisted, dripping mouth emits a cry that powerfully expresses the collective anguish of Guernica. The destruction of life is indicated by the profusion of crosses—so numerous that the), topple over one another in competition for space, an allusion perhaps to the mass graves that were then a largely unpublicized fact of war.

Burkhardt's knowledge of collective graves could not have come from firsthand combat experience. Beyond the draft age, he had spent the early part of World War II in a Southern California defense plant building airplane parts and the remainder finishing furniture for a film studio in Hollywood. His closest personal contact with war waobserving, as a child in Switzerland, the eerie red glow produced by bombs bursting. over the border mountains during World War I. This image is often conjured in his paintings,[15] but the crimson sky as a backdrop for battle has a long tradition in poetry

Figure 15

Hans Burkhardt, War, Agony in Death , 1939-40.

Oil on canvas, 78 × 114 in. California State University at Northridge.

Photograph courtesy Jack Rutberg Fine Arts, Los Angeles.

and painting, from Eugene Delacroix to Edmund Blunden.[16] For the most part, then, Burkhardt's vision of war drew primarily on his imagination, as well as cumulative associations from literature, the popular media, and the work of other artists. His work is best understood, not as an expression of the "reality" of war, but as a response to antecedent, technique, actual events, and, above all, his own intense feelings about the destruction and violence of war.[17]

Burkhardt's antipathy cannot be traced to any involvement with organized religion or politics; his preoccupation with death and suffering had much more personal roots. He spent his early childhood in Basel's industrial quarter, where his family's home stood in the shadow of a chemical factory and across the street from a rat-infested junkyard.[18] When Burkhardt was three, his father abandoned the family for America; a few years later, when his mother died of tuberculosis, he and his sister went to live in an orphanage. Years later, after moving to New York to join his father and stepmother, he lost both within a year, one to illness and the other to an automobile accident.

The theme of abandonment can be found in one of Burkhardt's first war paintings, The Parting (1939; Fig. 16). Although highly abstract, the image can be read as a man leaving his family to go to war. On the left, several children cry out, while on the right, their parents embrace for a final parting kiss.[19] This painting provides a template for

Figure 16

Hans Burkhardt, The Parting , 1939. Oil on canvas, 22 × 28 in

Photograph courtesy Jack Rutberg Fine Arts, Los Angeles

many of Burkhardt's later works, notably War, Agony in Death , where the "children" reappear as a personal shorthand for suffering. But there the "father-mother" configuration has metamorphosed into a monstrous weapon of war. The image projects Burkhardt's conflicted feelings of anger and loss toward his parents while doubling as a metaphor for the demonic forces of technology. On both levels of parable, victim and oppressor are conflated.

Burkhardt has been described as Goya's spiritual heir, and it is true that few artists since Goya have been as consumed by the brutality of war. But unlike Goya's Disasters of War (1810), Burkhardt's paintings dwell on the innocent victims rather than those responsible for war's atrocities.[20] Among his most horrific renderings of suffering are the concentration camp paintings, of which he made at least four during the course of the war. The first, painted in 1941, suggests two skeletal figures locked in an embrace. The threat of death is near, symbolized by two crosses at their heads. By 1942, the figures have collapsed into an undifferentiated heap, with only the most tentative characteristics of humanity to define them. Burkhardt unleashes some of his most savage

brushwork in this painting and its companion of the same year, with ragged, slashing strokes that express the full force of his fury. These paintings, however, are most remarkable, not for their emotional intensity, but for their prophetic imaging. Although it was common knowledge in America at the time that the Nazis had confined European Jews to concentration camps, the details of Hitler's gas chambers and crematoria were made public only in 1943. Even in 1944 most Americans remained oblivious to the genocide. According to the historian John Morton Blum, a poll taken in December 1944 revealed that much of the general public "knew Hitler had killed some Jews but could not believe that even the Nazis had methodically murdered millions."[21]

Skeletal forms appear in Burkhardt's paintings with increasing frequency toward the end of the war, culminating in one of his most harrowing paintings, VE Day (1945; Plate 5). The subject of victory in Europe might suggest something celebratory, but Burkhardt confronts the appalling cost of the armistice by presenting a panorama of horror that recalls the hellscapes of Bosch. The dead and wounded are shown in such profusion that they appear to rise ad infinitum beyond the canvas. In some cases, their bodies appear torn and mutilated. One disembodied member actually appears to pierce another, causing a cascade of blood. This painting, however, constitutes one of the rare instances in which Burkhardt specifies the gruesome details of war. Although he often implies an abundance of blood through a liberal use of red, Burkhardt largely excludes the horror of battle from his paintings. Nowhere do we find the rotting maggot-infested cadavers of Otto Dix, who painted the German battlefields of World War I. Compared with Dix's nauseating body-littered trenches, Burkhardt's VE Day provides a pleasure to the eye.

It is a paradox of Burkhardt's work—and indeed, of many modernist attempts to treat the theme of war—that a concern with technique often resulted in the artful rendering of a profoundly ugly subject. Many of Burkhardt's paintings present an unsettling conjunction of sensuality and death. Burkhardt certainly did not intend to aestheticize violence or to use his war paintings as vehicles for virtuosity, but that is precisely what he did. His paintings of atomic explosions, with their radiant colors and masterful handling of line, are especially dazzling.

Burkhardt embraced not only the aesthetic devotion of modernism but also its aversion to narrative, which precluded the concrete treatment of war found in the work of Dix or Goya. Although his paintings are for the most part tied to specific events, they show some of the same striving for universality that one finds in abstract expressionism. In most of Burkhardt's paintings, people appear, not as individuals, but as archetypes of humanity. Burkhardt shared abstract expressionism's ambition to express a content generic to all cultures, to speak what Elmer Bischoff called a pictorial Esperanto.[22]

Burkhardt's desire for unity, the flip side of his obsession with war, could at times verge on utopianism, as in One World (1945), a painting that exceeds even the idealism of Wendell Willkie's best-selling book of the same title published two years earlier. Going well beyond Willkie's call for global democracy, Burkhardt imagines a world in

which all the races have blended to form a single unified culture, symbolized by an abstraction of interlocking planes of color. A strain of optimism runs through much of Burkhardt's work. Many of his darkest war paintings of the 1940s contain a glimmer of hope, often suggested by the conventional landscape allegory of storm clouds beginning to break. Occasionally, Burkhardt's paintings serve as an arena for enacting his fantasies of political justice. As early as 1939 he painted Hitler hanging from a noose over the ruins of Germany. In later decades he would bury Lyndon Johnson for his complicity in the Vietnam War and Richard Nixon for his corruption of the government. But if Burkhardt occasionally found imaginative release through his art, the seriousness of political injustice was never far from his mind. His brand of escapism was not intended for amusement or diversion. Burkhardt's sober response to World War II was worlds apart from Clay Spohn's whimsical flights of fantasy.

Clay Spohn's Fantastic War Machines

In the summer of 1941, some six months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the San Francisco artist Clay Spohn began having recurring dreams about battling the Axis powers with fantastic weapons of war. "They were not nightmares," he recalled, "but like great spectacles of color."[23] Spohn took profuse notes on these dreams, waking in the middle of the night to make elaborate annotated "obsession drawings." Most of his more than two hundred ideas for war-related paintings never evolved beyond scrap paper, but at the urging of his good friend Charles Howard, Spohn produced enough finished works for an exhibition. A notorious procrastinator, Spohn worked on them until the very eve of their presentation. On February 22, 1942, two months after America entered the Second World War, Spohn's Fantastic War Machines and Guerragraphs premiered at the San Francisco Museum of Art.

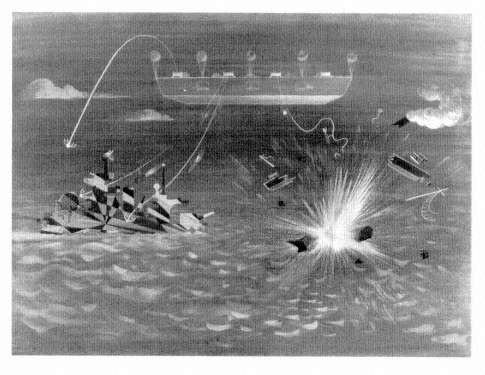

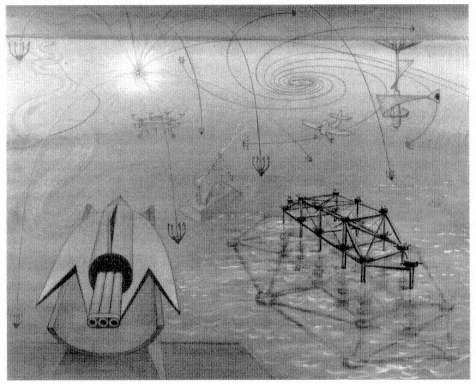

The critical reaction to Spohn's exhibition was alternately baffled and bemused. It was difficult to say whether the artist was ridiculing the war effort or merely indulging in escapist fantasy. The show consisted of nine meticulously drawn, elaborately captioned gouache renderings of weaponry, which, as one critic quipped, illustrated some very unorthodox ways of winning the war.[24]Hover Machine (Fig. 17), for example, showed a device that could snare enemy vessels from both sea and air at lightning speed with the grappling hooks it ejected on cables from lubricated windlasses. Tornado Machine depicted an electronically controlled cyclone; Spy Detector showed an ornately decorated vehicle with outsize spy glasses; Balloonic Uplifters represented brassiere-shaped nets to entrap enemy aircraft; and the mammoth Rolling Fort (Fig. 18) featured

Figure 17

Clay Spohn, Hover Machine , 1942. Gouache on paper, 15 × 20 in. The Oakland

Museum, gift of the Estate of Peggy, Nelson Dixon. Photograph by M. Lee Fatherree.

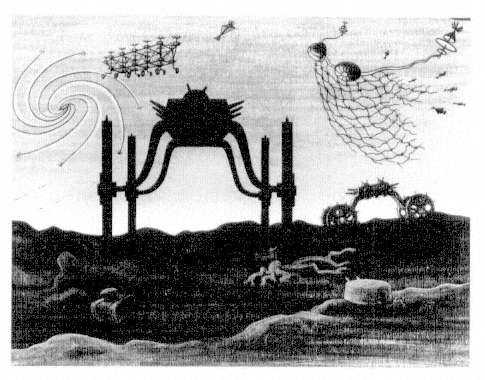

Figure 18

Clay Spohn, The Rolling Fort , 1942. Watercolor on matboard, 18¾ × 26 1/8 in.

Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, Logan, Utah.

Gift of the Marie Eccles Caine Foundation.

a chassis one hundred and twenty feet above the ground. Spohn's exhibition also included eleven drawings and gouaches of various war-related subjects, for which Douglas MacAgy, the show's curator, coined the term Guerragraph , from the Spanish word for war. At least one of the Guerragraphs anticipated the "Spy vs. Spy" cartoons of Mad Magazine , showing spies engaged in various ludicrous operations, such as peering at each other from around the corners of buildings and from other conspicuous hiding places.[25]

Spohn's War Machines and Guerragraphs have often been classified as surrealist, and indeed, Spohn borrowed liberally from that movement.[26] Stylistically, his approach was closest to that of René Magritte, Dalí, and Tanguy, who sought to fix dream-inspired images by illusionistic means. Spohn's work resembles that of these artists in its crisp delineation and smooth, unmodulated colors as well as in the artist's tendency, particularly in the Guerragraphs , to suspend forms weightlessly in a dreamlike landscape (Fig. 19). But Spohn's variety of madcap comedy is unusual in surrealism. His playful antics seem blissfully naive compared with the black humor of Magritte or Dalí. When the Europeans dealt explicitly with the subject of war, there was little lighthearted humor. Magritte's Black Flag (1937), for example, makes a striking contrast with Spohn's renditions. Magritte's war machines are equally fantastic and irrational, but their dark silhouettes are ominous and funereal. Hovering above a colorless landscape depleted of life, they could be, as Sidra Stich has suggested, the futuristic relics of a dead civilization.[27] Spohn was less concerned with the sinister implications of war, in large part because he did not subscribe to surrealism's Freudian view of humanity as inherently barbaric. Spohn preferred to focus on the positive elements of human nature, and he did not share the surrealist ambition to discommode the social status quo by revealing the dark and unruly workings of the mind. If, like the surrealists, Spohn hoped to short-circuit the intellect through humor and fantasy, it was rather to intensify the pleasure of life.[28]

In this sense, Spohn's approach was closer to Alexander Calder's than to that of any of the surrealists. Calder's whimsical mechanical sculptures may in fact have been an important stimulus for Spohn, since the two artists had known each other since their days at the Art Students League in New York and had worked in adjacent studios in Paris during the 1920s. It was apparently Spohn whose suggestion that Calder work with wire ultimately led him to invent the mobile.[29] Spohn's colorful kites and streamers and his kinetic Wind Machine for San Francisco's Open Air Show in 1941 were very much in the spirit of Calder's fanciful mobiles and circus toys.

Yet Spohn's War Machines were perhaps closer still to the preposterous contraptions of Rube Goldberg, then a popular cartoonist for the New York Evening Sun . Goldberg's mural Automatic Hitler Kicking Machine (1942) was as filled with impossible gadgetry as Spohn's inventions.[30] It would hardly be surprising if Spohn had admired Goldberg. since Spohn had also begun as a cartoonist.[31] Although he quickly abandoned cartoon work to pursue a career in painting, he continued to amuse himself and others with his

Figure 19

Clay Spohn, The Unsinkable Fort , 1942. Gouache, pencil, and crayon on paper,

17 ¾ × 21 in. Collection of John E Axelrod, Boston. Photograph by Michael Korol.

considerable comedic talent. Spohn was acclaimed in San Francisco in the 1940s particularly for his zany assemblages—the best known being his Museum of Unknown and Little-Known Objects (1949), which featured such whimsical exhibits as Bedroom Fluff , a collection of dust balls Spohn gathered from under a friend's bed; Old Embryo, a rubber Halloween mask floating eerily in a chemist's flask; and Mouse Seeds , a jar of mildewed rice. Spohn described these creations as "prankisms," acknowledging that they lacked the intellectual underpinnings of dada or surrealism.[32] Like many American modernists, Spohn approached art instinctually rather than theoretically.[33] Indeed, he was attracted to humor precisely because it afforded "a kind of free release from the bondage of dogma."[34]

The moment when Spohn's Fantastic War Machines debuted at the San Francisco Museum of Art could hardly have been more tense. In early 1942 the Japanese were rapidly overpowering the small, ill-equipped American garrisons on Pacific islands. The

fall of Bataan in the first few months of 1942 was probably the nadir of the war for the Allies, coming shortly after the loss of Singapore and Hong Kong and the sinking of the great British battleships the Prince of Wales and the Repulse .[35] Although most San Franciscans experienced these events only in news reports, the war was difficult to forget with such daily reminders as the convoys of warships filing steadily through the Golden Gate, with Angel Island overflowing with German and Japanese prisoners of war, and with such strange sights as the enormous Kaiser Shipyards, so busy producing Liberty ships that, as Dos Passos reported, they glowed all night long like forest fires.[36] Not only was San Francisco the major supply port for troops and munitions fueling the war effort, but it was also America's lifeline. The daily plasma drives and Red Cross blood banks springing up in such places as the California School of Fine Arts on Russian Hill were a grisly reminder that a massive war was on.

The anxiety was particularly acute in the months just after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. As the most strategically important port in the country, and hence America's front line, San Francisco was consumed by fear of becoming the next target. Blackouts were nightly events, and posters around the city warned civilians and soldiers alike to "zip your lip" since "loose lips sink ships." The paranoia can be measured by the rumors that filled the local newspapers. One story accused Japanese-born farmers of planting their tomatoes in the shape of an arrow to guide enemy bombers.[37] Another claimed that the Italian residents of North Beach were protecting their homes from air attack by painting swastikas on their roofs.[38]

Spohn's humorous spies and fantastic weaponry thus clearly ministered to a desperate need to relieve the tension.[39] Yet while Spohn certainly intended that the War Machines and Guerragraphs amuse, he also meant them as provocative satire. As Spohn's biographer, David Beasley, has written, these paintings "mocked imaginatively their original unworkableness as much as they mocked the seriousness of war."[40] They suggested the fiction of the government's and the media's grandiose claims that American weapons were invincible. The critic who described Spohn's War Machines as "Popular Science gone nuts"[41] had clearly not picked up a recent issue of the magazine, or he would have known that Spohn's ideas were not so distant from some of the armament designs seriously proposed at the start of the war, such as John Hodgdon's "Gyroscope Torpedo" and George Walker's flying "Mosquito Boat."[42] Spohn's War Machines , for which he concocted elaborate deadpan captions, deftly parodied such hopeful inventions. But it was not necessary to look at magazines specializing in science and industry; publications like Time and Newsweek were filled with praise for the ingenuity of American war technology, with the sort of bravado voiced in an advertisement for Corsair bombers that appeared in the December 1942 issue of the Saturday Evening Post : "Woe to any Jap or Nazi that tries to slip away! This new Navy fighter has 'got the drop' on everything under the axis sun!"[43]

As a veteran of the First World War, Spohn was somewhat skeptical of Allied slogans about swift victory. His assemblage Wake Up and Live , constructed around the same

time as the War Machines , expressed his concern that, as he later explained, "if we didn't wake up to the real facts that were going on with the war in Europe and so on, we might find ourselves in a bad way."[44] Wake Up and Live , consisting of a painted fly in a shadow box that could be swatted by pulling a chain, offered a graphic image of what could happen if America merely remained "a fly on the wall" during the conflict. By ridiculing America's claims to military prowess, the War Machines and Guerragraphs conveyed a similar warning about the need for preparedness. Spohn could scarcely have known how close to the truth he was. Only the military elite and those who did the actual fighting knew the deadly inefficiency of such highly touted war machines as the B-17 Flying Fortresses.[45] As Paul Fussell observed, few could have predicted that "before the war ended the burnt and twisted bits of almost 22,000 of these Allied bombers would strew the fields of Europe and Asia, attended by the pieces of almost 110,000 airmen."[46]

The GIs and the Canvas: The Artists of the California School of Fine Arts

Abstract expressionism is often interpreted as a response to such horrific revelations as the Nazi death camps, Hiroshima, and the threat of global holocaust. The standard art-historical account describes the rejection of identifiable subject matter as a corollary to the acute anxiety produced by these events, coupled with profound disillusionment with the political systems that made them possible. Recently, a number of scholars have carried the argument further to suggest that the decision to paint abstractly reflected a political neutrality born of this disillusionment. With social realism tied to outworn Marxist ideologies, and American Scene painting linked with the conservative "America Firsters," abstraction represented a noncommittal middle ground. Some art historians have interpreted this disengagement as an unwitting collusion with cold war centrism,[47] while others have explained it as a demonstration of anarchist sympathies.[48]

It is illuminating to test these hypotheses against the San Francisco abstract expressionists, who were far more forthcoming about their political views than their East Coast counterparts. The San Francisco group presents a profile strikingly different from that of the New York School. Clyfford Still, probably the best known of the San Francisco abstract expressionists, apparently joined the Right after the war, while a number of others remained faithful to the Left, including Hassel Smith, Robert McChesney, Ronald Bladen, and Edward Corbett. Although the Bay Area had been a center for anarchist activity since Alexander Berkman published his radical labor paper the Blast during the teens, none of the abstract expressionists ever became involved with that movement, or with any of its libertarian offshoots that flourished among the West Coast literary avant-garde during the 1940s.[49] Yet there can be no denying that the war was the shaping factor in their art. Unlike the New York School, most of the San Francisco artists had firsthand experience with the war. Of the best-known New York abstractionists, by contrast, only Ad Reinhardt served in uniform.[50] But to

see their painting as the product of alienation and angst is to simplify a complex phenomenon. Although such an argument could be made for Frank Lobdell, it would not hold for Richard Diebenkorn, or for Smith.[51] Yet the work of each cannot be understood without taking into account the war, which fundamentally shaped their art and their worldview.

John Grillo's painting had little to do with disillusionment but a good deal to do with the war. He was among the first of the veterans to arrive, in 1946, at the California School of Fine Arts, which was soon to become the center of abstraction on the West Coast. Douglas MacAgy the school's director, remembered Grillo vividly as a "fiery young sailor" who showed up at the school, still in uniform, bearing a portfolio of tattered paintings from overseas. After looking at Grillo's work, MacAgy concluded: "Far from the blunt detachment represented by the Time-Life-Fortune type of war record, these fragments expressed the searching experiences of an individual in the hands of war."[52] Yet even though Grillo had been stationed on Okinawa, among the bloodiest combat sites of the war, his paintings remained decidedly cheerful. Grillo's painting virtually exploded with high spirits on his arrival in San Francisco after the war, when he became something of a legend for executing his canvases from across the room. These paintings have none of the anguish of Pollock or the mystery of Rothko. Instead, they exude a sensuality and delight in the manipulation of paint, with colors that are radiant, in some cases phosphorescent.

Perhaps more than any other San Francisco abstract expressionist, Grillo expressed the euphoria that briefly accompanied the war's end. Although some of the artists came out of the war harboring feelings of guilt and unease—notably those who, like Corbett and Lobdell, had experienced too much violence firsthand—the tenor of the period immediately following the founding of the United Nations was one of tremendous optimism. Most exhilarating for the veterans was being free at last from the bondage of the military. For many, the end of the war represented less an escape from mortal danger than a liberation from what Leonard Woolf called the "negative emptiness and desolation of personal and cosmic boredom."[53] Only a fraction had actually served in combat; the rest were consigned to the tedious tasks of administration, transportation, and supply, where waiting itself became the primary activity.[54] Most, like Elmer Bischoff, experienced the war as little more than "repugnant minute to minute, day in day out imprisonment."[55] Perhaps more devastating than the sheer boredom was the suppression of individual personality. As one of sixteen million GIs, the soldier in the Second World War was even more anonymous than his counterpart in the First.[56] The military's rigid hierarchy instilled a powerful antagonism toward bureaucracies of any kind. George Stillman spoke for many at the California School of Fine Arts when he said, "We had all been fed up with regimentation, with being put in a uniform and told what to do. We were looking for a way out of that discipline—a way to be individual, a way to be human."[57]

The antiauthoritarian ethos was especially strong at the California School of Fine Arts, where the traditional student-instructor roles were blurred by the leveling experience of the war. As Bischoff remarked, because they had all been in the service together, "There were not really instructors and students as much as there were older artists and younger artists."[58] Douglas MacAgy was fully aware of the returning veterans' aversion to institutional environments. As director from 1945 to 1950, he was determined that the school not "impose a ready-made set of visual arrangements or prescribed meanings," but instead pay respect "at all times to the ultimate integrity of the individual artist."[59] Rather than provide a set of a priori standards, MacAgy's instructors encouraged experimentation. Clyfford Still may have been draconian on matters of artistic conscience, but he refused to judge individual paintings.[60] Similarly, Clay Spohn implored his students never to follow the precepts of a master, but to leave open an infinite range of possibilities: "Art is not only free of anything that has to do with the dogmatic, but it is the essence and spirit of freedom. It can be developed only when the mind and spirit are completely free and released. Limitation is the enemy of free expression."[61]

Grillo's spontaneous method of painting was one way for the veterans to release their pent-up desire for personal expression. Smith, Diebenkorn, Bischoff, and David Park were among those who found release in explosive canvases that employed the drip, the splatter, the smear, and the gesture. Although not every artist worked in a rapid-fire fashion—Corbett, Still, and Lobdell are the notable exceptions—all the San Francisco painters rejected the impersonality of geometric abstraction. Whether in the form of cubism, neoplasticism, or Bauhaus design, such abstraction seemed incapable of commenting on the world. Geometry was also associated with a sympathetic view of technology and science that was no longer tenable after the war.[62] By the late 1940s, the machine aesthetic, as a subset of classicism, had come to signify the forces of tyranny and oppression. Thus, for Diebenkorn, geometric abstraction "equalled sterility"; for Corbett, it represented a "straitjacket"; and for Still, it meant nothing less than "totalitarian hegemony."[63]

The aesthetic consequences of this anticlassicism among the San Francisco abstract expressionists involved more than a refusal to paint geometric shapes. Indeed, nearly every aspect of their sensibility can be seen as antithetical to the ideals of classicism. They rejected clean, smooth surfaces and clear hues in favor of rugged textures and earthen, sometimes muddy, colors. In their works clarity, order, and stasis gave way to the contrary romantic qualities of dynamism, ambiguity, and imprecision. This distaste for static forms included a reluctance to fix edges with delineating lines. As MacAgy observed, the quantitative, delimiting function of the enclosing line made it a paramount symbol of classicist rationality.[64] Even the borders of a frame were considered too confining. Still was especially adamant in this regard, declaring: "To be stopped by a frame's edge was intolerable; a Euclidean prison. It had to be annihilated, its authoritarian implications repudiated."[65]

There is a powerful aura of protest around much of Still's work that appealed to the former GIs in San Francisco. It was his "anti-color" and his "willingness to use something really raw and brutal," as Jack Jefferson put it, that won him so many admirers.[66] As the 1940s came to a close, a number of events transpired to make a dark, forbidding variant of abstraction more relevant to the times than Grillo's joyful expressionism.[67] The rising threat of global atomic warfare and the beginning of the Korean War in 1950 contributed to a general malaise and to a growing sense of betrayal among the veterans. "We felt we had been betrayed by words and by the wordsmiths," John Hultberg recalled. "We had won the war and that was supposed to bring happiness, but we weren't sure things were [getting] any better."[68] The war had been sanitized and Norman Rockwellized for the troops and particularly for the homefront, and now the cycle was beginning again.[69]

Disillusionment in the 1950s was especially acute among those who had sacrificed the most during the war, the few who had experienced the devastating psychological impact of combat. Compared with the pastel confections of Diebenkorn, who remained in relative comfort as an art student at Stanford and the University of California for most of the war, the canvases of Jefferson, who served on Guadalcanal at the height of action, are dark and morose, mostly in grim shades of gray, brown, and black. The black enamel paintings of Corbett, who nearly lost his life in the Battle of the Coral Sea, are among the angriest abstract expressionist paintings from the early 1950s (Fig. 20). Corbett, who had registered his horror of the Holocaust with a chilling drawing of bodies stacked like cordwood,[70] described his black paintings as the "expressive complement" of "vast conglomerates of evil."[71]

But of all the San Francisco abstract expressionists, the one who became most obsessed with the hypocrisy and brutality of the war, translating this obsession into powerful paintings of personal anguish, was Lobdell. From an essentially formal preoccupation with the innovations of Klee and Picasso, Lobdell developed toward the end of the 1940s an aesthetic that had no room for beauty or sentimentality—which in his opinion served only to cloak the harsh realities of postwar society.[72] Lobdell's work began to take on a disturbing cast around 1948, with a group of paintings and lithographs that recall bones, tendons, and intestinal coils.[73] As a lieutenant in the infantry in Germany, he had witnessed horrific slaughter on the front lines.[74] Fellow California School of Fine Arts artist Walter Kuhlman remembered Lobdell's recurring nightmares about "blood and guts spilling out of men."[75] The horror and nausea of such experiences are powerfully conveyed in an untitled work circa 1948 that suggests torn limbs dripping with blood.

As the 1950s progressed, Lobdell's paintings became increasingly ominous and brooding. The chalky white grounds of his earlier work gave way to dense and impenetrable blacks and grays in agitated impastos. As in the work of Still, these impastos are divested of all the sensuality usually associated with the technique: they are the product of slow accretion rather than of oil-laden brush strokes. Often, as in the Oakland

Figure 20

Edward Corbett, Untitled , ca. 1950-51. Oil and enamel

on canvas, 60 × 50 in. Collection of William M. Roth.

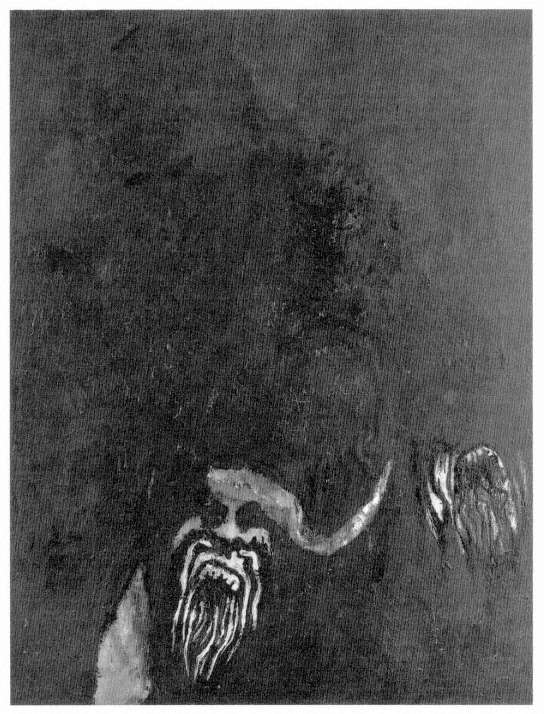

Figure 21

Opposite : Frank Lobdell, January, 1955 , 1955. Oil on canvas, 69 5/8 × 53½ in.

The Oakland Museum, gift of Mrs. Robert Chamberlain. Photograph by M. Lee Fatherree.

Museum's January, 1955 (Fig. 21), Lobdell's surfaces are as dry and parched as cinder. This painting evokes a fire-charred hell, the blackness pierced by flickering streaks of orange and red, suggesting flames as well as mouths open wide in agonizing screams. As we have seen, the cry of anguish was a theme that had earlier occupied Burkhardt, as it had Lebrun, Picasso, and Bacon. It is one of many war-engendered motifs—along with the crucifix, the savage beast, and the shadowy woods—that typify the painting of the period both in Europe and America, whether one looks to London, Paris, New York, Los Angeles, or San Francisco.

Conclusion

The years from 1941 to 1951 fundamentally transformed the art of California, no less than that of the country as a whole. In that decade, regionalism and other realist tendencies antagonistic to European influence gave way to a powerful tide of modernism that ultimately swept them off the stage entirely. New York is generally regarded as the generative site for this phenomenon, but in fact the trend toward abstraction was remarkably broad, apparent not only in galleries and studios in Manhattan, but in art schools and regional exhibitions across the country.[76] California's participation in the rise of modernism during the postwar era, then, should not be understood as a passive absorption of trends initiated elsewhere, but rather as a profound response to historical pressures brought about by the war. Although most of the strategies Californians found for expressing themselves had counterparts on the East Coast and in Europe, their art was by no means imitative or homogeneous. While it conformed to the categories of style found in other parts of the country—mostly surrealism, cubism, expressionism, and various admixtures—the range of expression was as varied as the population. Of interest here, however, as throughout much of the present volume, is not merely the concurrency of California modernism during the 1940S, but the question of its distinguishing characteristics. Was there anything singular about it that might be attributed to the physical and psychological environment?

Regionalism is a particularly complex issue for the period in question, because the very notion conflicts with the premise of internationalism that underlay modernist painting. And certainly modernism was never so zealous in crusading against cultural chauvinism as it was during the war years. To embrace the "international idiom of twentieth-century painting," as abstraction was commonly conceived then, was to con-

demn localism in art as well as politics. [77] As Mark Tobey remarked in 1946, the regional could be stressed only "at the expense of the inner world" and "the understanding of this single earth." [78] As different as their aesthetics were, Burkhardt, Spohn, and Lobdell would each doubtless have agreed with Robert Motherwell that "to fail to overcome one's initial environment is never to reach the human." [79]

Given this prevailing viewpoint, California modernists strove, not to emulate local traditions, but rather to transcend the particulars of time and place. Paradoxically, by reacting against indigenous conventions, Bay Area artists such as Corbett, Still, Smith, and Lobdell produced a kind of reactionary regionalism. During the late 1940S, they deliberately emptied their work of the bright, sunny colors associated with West Coast painting, notably the popular California watercolor school, which concentrated on western agrarian and coastal scenes. Los Angeles modernists also rejected local references. Burkhardt and Feitelson, McLaughlin and Lebrun—each sought a timeless, transcendent modernism that had little to do with the milieu of Southern California.

Yet in spite of the attempts to universalize, certain idiomatic traits took hold; certain strains of modernism became more prevalent in California than elsewhere. Abstract expressionism caught on more quickly in San Francisco than in other parts of the country, while Los Angeles became a center for figurative expressionism and hard-edge abstraction.[80] To some extent, these variations were due to the extraordinary force of individual personalities: Still's in San Francisco, Lebrun's and Feitelson's in Los Angeles. As the 1950s progressed, the differences between Northern and Southern California became ever more pronounced. By the 1960s the abstract classicism of Feitelson and McLaughlin had given birth to what became known as the L.A. look—Southern California's ultraslick, squeaky-clean variety of formalist abstraction. In Northern California an entirely different sensibility had taken hold: the determinedly individualistic, romantic antiformalism typified by the work of William Wiley, Joan Brown, and Robert Arneson. Ultimately, however, we must acknowledge that even if lineages can be traced to artists such as Still and Feitelson, a psychology of place, rather than the impress of a few innovators, encouraged the polarities of the 1960s and continues to inform the various regionalisms existing today.