Visual Music and Film-As-An-Art Before 1950

William Moritz

During the silent film era, when everything had to be expressed visually, the trick effects of Georges Méliès, the zany "surreal" improbabilities of comedies, the experimental decor of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari , the expressionistic camera movement of The Last Laugh , or the shock editing of Potemkin were all played and found their way into the vocabulary of commercial features. Yet a distinctly modernist, avant-garde, or "experimental" film also emerged, partly through the participation of artists such as Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Salvador Dalí, and partly because of the vigor with which filmmakers like Germaine Dulac and Sergei Eisenstein wrote about the viability of cinema as a vehicle for a modernist art that could add the dimension of time (including controlled duration of viewing, complex juxtaposition, and so forth) to the other elements that concerned contemporary painters and sculptors: abstraction, expressionism, significant form, integrity of materials, heightened perception, new technology.

The borderline between "experimental film" and "the movies" thus remained ill-defined: "art films" or "avant-garde films" were more the question, since expressive, experimental techniques distinguished certain films as more artfully, consciously made, more advanced than the run-of-the-mill commercial products, and those "art films"—including animation and live action, long and short, older and more recent films from all around the world—formed the basis of a critical and popular cult of film art that by 1930 was celebrated internationally in cineclubs and theaters, magazines and books.

Since European art films, classic silent films, or the avant-garde shorts of the 1920s were not screened at every theater, the visually literate of Los Angeles kept track of what was showing at the Filmarte Theatre on Vine Street. During the 1930s art films occupied a permanent place on the Filmarte screening schedules—and if you were lucky, Dudley Murphy, the primary filmmaker of the famous Ballet Mécanique , might show his personal copy of that film (with the brief erotic flashes still intact among the

pumping machines), which James Whitney, Harry Hay, and Man Ray saw there.[1] Or in the 1940s, at Clara Grossman's American Contemporary Gallery (the linear descendant of Stanley Rose's bookshop and gallery, located in the Artisan's Patio on Hollywood Boulevard near Las Palmas), you might well sit next to D. W. Griffith or Lillian Gish or Man Ray or the Whitney brothers while watching a classic art film.

California produced a stream of experimental films paralleling those made by the emerging European avant-garde. One of the earliest experimental filmmakers in California was Dudley Murphy, who studied at M.I.T. and served as a pilot in Europe during World War I before coming to Hollywood to work as an art director and apprentice cameraman at the studios—as well as writing movie reviews for the Los Angeles Evening Herald . Inspired by Theosophy, he longed to make "Visual Symphonies" that would combine the best of music, dance, and the visual arts through the unique capabilities of film. In the summer of 1920, he shot his first film, The Soul of the Cypress , on the rocky shoreline around Point Lobos. It was synchronized to Debussy's Afternoon of a Faun and starred his wife, Chase. Critics greeted the premiere of the film, July 10, 1921, at the Rivoli Theatre in New York, with lavish praise: the critic for Film Daily noted how "it breaks away completely from the stuff that has been repeated so often, and makes a decided step forward both in the artistic sense, and in pictorial qualities"; the critic for the New York Times named it among the best films of the year, saying it was good to see that "the camera can still charm by purely photographic effects."

Murphy made two more "Visual Symphonies" in California—Aphrodite (shot on the beach at La Jolla and Los Angeles, with Katherine Hawley, a dancer of the Duncan/ St. Denis schools) and Anywhere out of the World (again with Chase, at Palm Springs)—and then three in New York. In 1923 he went to Paris, where he worked on the experimental short Ballet Mécanique (which was partly funded by Fernand Léger). Afterward, he returned to Hollywood, where he made a dozen features and several musical shorts, including St. Louis Blues with Bessie Smith, Black and Tan with Duke Ellington, and Emperor Jones with Paul Robeson. These commercial films (and two features he shot in Mexico during the 1940s) show imaginative modernist touches in montage and dance sequences despite the occasional banality of their studio scripts. In 1941 Murphy helped pioneer "soundies," three-minute films of jazz and popular songs that were shown on small screens attached to juke boxes—a predecessor of MTV.

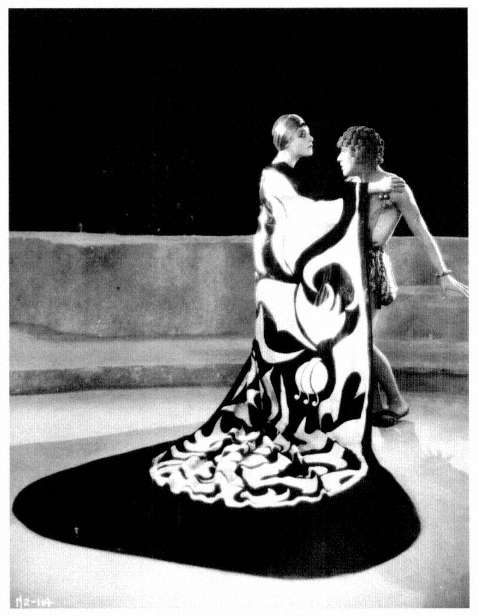

Alla Nazimova's screen version of Oscar Wilde's Salomé (Fig. 77) counts as not only one of the earliest but also one of the most notorious art films produced in California. Nazimova's popular success onstage and in movies gave her the financial means to make this personal film, which she directed and scripted. She also performed the role of Salomé. Her lover, Natacha Rambova, designed extravagant black-and-white costumes and sets that suggested the Aubrey Beardsley illustrations for the original edition of Wilde's play. Nazimova carefully assembled a cast of homosexual actors (as befitting a work by Oscar Wilde) and encouraged them to perform with stylized, abstracted

Figure 77

Alla Nazimova as Salomé and Samson DeBrier as the Page in Nazimova's Salomé (1922).

Photograph courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

gestures and poses. The film was shot during 1922 in a small independent studio just a block away from the huge set for the walls of Babylon from D. W. Griffith's Intolerance (1916) that was still standing then.[2] At its December 31, 1922, premiere, both critics and audiences found Salomé a decadent, quasi-humorous curiosity, and it has remained a camp classic, its images appearing on 1960s psychedelic rock posters and contemporary greeting cards.[3]

Exactly how radical the abstraction in Nazimova's film was can be judged from comparison with the Theda Bara version of Salomé from 1918. While Bara's decor and costumes also attempt to give the flavor of Beardsley, they are hopelessly cluttered with Victorian "orientalism," and while the acting of Bara's players seems stagey, it also aspires to conventional realism—Griffith's Intolerance would supply a close parallel. By contrast, Nazimova's production boasts a spare elegance as well as fanciful extravagance that defies any specific historical reference and suggests (for example, in the cluster of white spheres that float about Nazimova's head in one scene) an abstract timelessness. In their expressionistic performances, Nazimova's actors display iconic moods rather than simulate realistic psychology.

Nazimova's Salomé is best understood in the context of the art film: on one side The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (which premiered in Germany in February 1920, in the United States in April 1921), which adapts avant-garde stage styling to create a stunningly eccentric movie experience, credible in its own terms, and on the other side later experimental films (involving such diverse filmmakers as James Broughton, Jack Smith, Kenneth Anger, the Kuchar brothers and Andy Warhol), which use elaborate, deliberately stylized decor and acting to explore forbidden sexuality. Perhaps, then, it is no accident that Samson DeBrier, the protagonist of Kenneth Anger's 1954 film Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome , played the anguished page boy in Nazimova's Salomé , under the stage name Arthur Jasmine.

The Los Angeles painter Warren Newcombe developed a special process for using painted backgrounds in films and worked as a special effects expert, first for D. W Griffith and David O. Selznick, then at MGM, where he won an Academy Award in 1948 for his work on Green Dolphin Street .[4] In 1922 and 1923 he shot two imaginative short films, The Enchanted City and The Sea of Dreams , both of which employed the Newcombe process: all the backgrounds were paintings. The New York Times , February 6, 1922, praised The Enchanted City (Fig. 78), a futuristic fantasy, for its "impressive" camerawork, "compositions of masses and lines, expressively shaded and lighted." The reviewer complains, however, that the "fantastic story lacks vitality" and recommends that "you just look at the different scenes as you would view pictures in a gallery," because "they have a strong appeal to the eye." In the context of later experimental films (for example, those of Gregory Markopoulos or Joseph Vogel), perhaps the "story" was less important than the painterly values of images.

That these film artists established relationships with the commercial movie world is hardly surprising: 35mm filmmaking was cumbersome and expensive—and to a certain

Figure 78

Original poster for Warren Newcombe's Enchanted City (1922).

Photograph courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

extent kept as a trade secret by commercial enterprises—so most people would need to learn the craft professionally, and once they had demonstrated their mastery of film with an imaginative, dazzling short, they would find it hard to resist offers to work in the industry. Several artists went into commercial filmmaking after making a single experimental film: Charles Klein (The Tell-Tale Heart , 1928), Dr. Paul Fejos (The Last Moment , 1928), Charles Vidor (The Bridge , 1929).

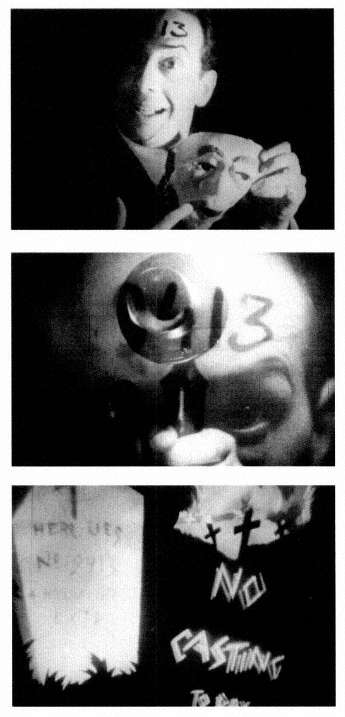

Robert Florey and Slavko Vorkapich, the makers of perhaps the most famous American experimental film of the 1920s, The Life and Death of 9413—A Hollywood

Extra (Fig. 79a-d), also enjoyed long careers in Hollywood. Florey came to Los Angeles from France in 1921 to be a Hollywood correspondent for European film magazines but quickly became involved as an assistant in studio films.[5] Vorkapich, a Yugoslavian, was studying painting in Paris when he saw Griffith's Intolerance and decided cinema was the art form of the twentieth century; he came to Hollywood, where he worked as an extra. He eventually sold one of his oil paintings for enough money to buy a camera, which he and Florey used to make Hollywood Extra . Florey wrote, directed, and acted in the film. Vorkapich designed the models and trick effects, edited the film, and shot much of the footage, although the live actors were filmed by Gregg Toland, who would later be cameraman for Citizen Kane . The twelve-minute film, a genuine little masterpiece, cost less than one hundred dollars. Using expressionistic miniature sets and dramatic moving lighting, imaginatively combined with live-action shots of Hollywood and stylized comic acting, Florey and Vorkapich effectively convey the plight of the hundreds of people who flock to Hollywood hoping for stardom. The brilliance of Hollywood Extra lies in its use of cinematic potential, not only in blending live action with trick shots, but also in conceptualizing rhythms (the actor's repeated climb up the staircase to success, like the washerwoman loop in Ballet Mécanique ) and camera viewpoints (the low-angle shots against a black void to suggest the power of producers and critics, used again later in Citizen Kane ). The comic acting and Florey's genuinely witty, ironic touches—the absurd masks, "blah-blah-blah" as the only spoken words, the CASTING and NO CASTING TODAY signs at the gates of Heaven—linger satisfyingly in the viewer's mind.

Following the great success of Hollywood Extra in June 1928, Robert Florey quickly made two similar expressionistic shorts, Loves of Zero and Jonathan the Coffin Maker , before becoming a feature director at Universal, Warner Brothers, and Paramount. Slavko Vorkapich became one of the great Hollywood editors, creating montage

Figure 79

Above and next page: The Life and Death of 9413—A

Hollywood Extra (1928), by Robert Florey and Slavko Vorkapich:

Vorkapich's model sets; Jules Raucourt as 9413, with his

Actor's face; Waiting for the call; The death of 9413.

Figure 80

Boris Deutsch's Lullaby (1929): The Demons.

sequences for many MGM features. In 1940 he collaborated with John Hoffman on two experimental short films, Moods of the Sea and Forest Murmurs , which synchronized beautiful nature photography with classical music through dynamic editing. Hoffman, a Hungarian-born MGM editor responsible for such montage sequences as the famous earthquake in the 1936 film San Francisco , had also made a lyrical landscape film, Prelude to Spring . He later directed features, including the 3-D production Bwana Devil .

In the wake of the much-publicized low-budget Hollywood Extra , the painter Boris Deutsch also made a low-budget personal art film in Los Angeles. He was born in Riga, studied painting in Kiev and Berlin, and fled across Russia in 1916 to the United States, where he worked in a Hollywood studio from 1919 until 1922.[6] Although hired at first as a designer, he gradually acquired a familiarity with the whole filmmaking process that allowed him to make, early in 1929, the fifteen-minute film Lullaby (Fig. 80) privately, for less than five-hundred dollars, some of it borrowed from the Russian refugee actor Michael Visaroff, who also played the villain in the film.[7]Lullaby depicts the psychological trauma of a Jewish woman (well acted by Deutsch's wife, Riva) employed as a servant in the house of demanding and abusive Christian Russians. The servant is charged with keeping the baby quiet during a drunken party, and when she

is slow to serve at table as well (and loath to uncover her hair, following Jewish custom), she is beaten. As the tension mounts, she is seized by a momentary urge to kill the baby but flees the house instead.

Deutsch uses the moody expressionistic visuals and symbolic touches characteristic of the art film to convey the heroine's psychological state. During her crucial bout with hysterical madness, images of her face are intercut rhythmically with abstract patterns in writhing turmoil and with the faces of demons, expressionistically painted in the style of experimental Yiddish theater.[8] And as she flees her house of employment, through Deutsch's special-effects photography the twisted buildings of the village seem to weigh down on her and assume the face of her tormentor. Deutsch also develops the cinematic potential of many scenes, by intercutting the similar faces of the Virgin Mary in an icon (painted by Deutsch) and the servant, or by shooting the accordionist in some nearly abstract diagonal compositions. Unfortunately, the only known print of the film is in poor condition—even the end title is spliced on from another source, so it is not clear that the print is complete. But enough fine touches are visible to establish that Deutsch's work prefigures the "psychodramas" of California experimental film of the 1940s.

While European art film styles and techniques permeated experimental films in Los Angeles, a brilliant 1937 satire, Even as You and I (Fig. 81a-c), definitively rejected that influence—at the same time that Los Angeles painters such as Helen Lundeberg, Lorser Feitelson, and Knud Merrild, with their postsurrealist manifesto, celebrated their independence from European trends.[9] The 1936 exhibition of dada and surrealist art at New York's Museum of Modern Art splashed fantastic images across the pages of American newspapers and magazines: the newly founded Life magazine, in its fourth issue, December 14, 1936, gave it a four-page spread (with color), including Meret Oppenheim's fur teacup and Dalí's Persistence of Memory . And Time put Dalí on the cover of the December 14, 1936, issue.

Far from the world of limp watches and fur teacups, the Hollywood Film and Foto League, in a decaying mansion that provided cheap lodging, working space, and social activities for dozens of young leftist artists, sometimes screened Soviet films and promoted documentaries about poverty and workers' problems.[10] Three artists who often met there (and at the Filmarte Theatre)—the Works Progress Administration (WPA) photographers Roger Barlow and LeRoy Robbins and the agitprop actor Harry Hay—were struck by the incongruity of the surrealist fine arts juxtaposed in a magazine with an advertisement for a Pete Smith contest for the best short film, the prize for which was a trip to Hollywood. They decided to make a spoof film chronicling what might happen if innocent amateurs tried to enter a "fine art" short surrealist film in this contest. The three men play naive versions of themselves in the frame story about the contest and filmmaking, and they collaborated on episodes in the film-within-a-film, The Afternoon of a Rubber Band , a pungent send-up of avant-garde clichés, including balloon heads from René Clair's Entr'acte , pistol games from Hans Richter's Ghosts

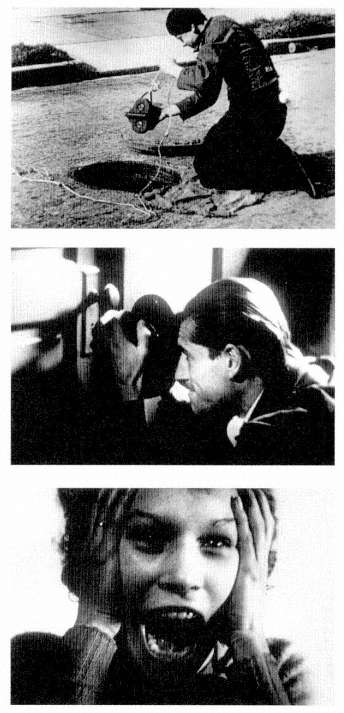

Figure 81

Even as You and L by LeRoy Robbins, Roger Barlow, and Harry

Hay (1937): Harry Hay lowering his camera down a manhole;

Roger Barlow shooting through a keyhole; the terrified observer.

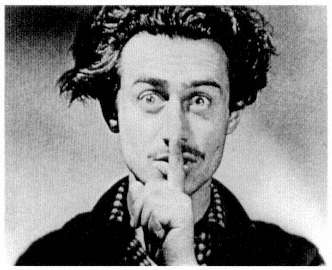

Figure 82

Even as You and I : Hy Hirsh as the Idiot Savant.

before Noon , and the rival editing theories of G. W. Pabst (the cannibalization of a baby implied by clever cutting together of many brief shots) and Sergei Eisenstein (a steam-roller running over a snail puffed into an epic confrontation through paced intercutting of actions and reactions).

In the film another friend of theirs, Hy Hirsh (a cameraman and still photographer who had been working in the Hollywood studios; he would have a distinguished career as an experimental filmmaker in the 1950s), played the role of a grinning idiot savant who periodically admonishes the audience to be quiet (Fig. 82)—a bit they had seen in one of the Soviet films that played frequently in Los Angeles. The hilarious satire in Even as You and I contains a serious implication: that the European masters like Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel may have "done it all," leaving no room for fresh experiments, aside from parody.

Harry Hay and LeRoy Robbins, however, collaborated in 1938 on a second film, Suicide , in which Hay played an emotionally tortured actor who, confusing his own emotions with those of various characters he has played, contemplates killing himself. Hay recalls that some of the shots were single long takes in which he had to portray several different thoughts and feelings overtaking the actor. Other scenes showed him in the makeup and costumes of stage roles, but he is not sure how they were blended, since he was in New York when the film was completed and did not see it projected. Perhaps in making Suicide , Hay and Robbins found a fresh formula for expressing this personal psychological drama, and thus showed a way out of the Los Angeles

Figure 83

Meshes of the Afternoon , by Maya Deren and Alexander

Hammid (1943): Florence Pierce as the Nun with the mirror face.

experimental film's aesthetic cul-de-sac. But unfortunately, all copies of the film may be lost.

Lacking copies of Hay and Robbins's Suicide , we must credit another artist with finding the way out of the cul-de-sac: a remarkable woman named Maya Deren, who was born in Russia but came to Syracuse, New York, at age five when her psychiatrist father took a job there.[11] In the 1930s, after graduating from the University of Syracuse, she became deeply involved in leftist politics, married and divorced, and then became interested in anthropology. A fascination with the mythic/ritual aspects of human behavior led her to Haitian Vodoun as a living religion and to Katherine Dunham's black dance troupe, which incorporated traditional rituals into their art (Dunham had done her master's thesis on Haitian Vodoun and dance).[12] Deren traveled with the dancers in 1941, when the troupe moved from New York to Los Angeles, where, at a party given by the art dealer Galka Scheyer, she met a Czech immigrant filmmaker, Alexander Hammid (originally Hackenschmied), whom she married in 1942. Hammid had been active in experimental filmmaking in Prague around 1930 and had made a subtle and fascinating film, Aimless Walk , which followed a young man who wants to get out of the city for an afternoon. At each point when he equivocates about going farther, he splits into two figures, one of which goes on while the other observes and turns back.

Although the refugee Hammid had no print of this film to show, his enthusiasm for personal, imaginative filmmaking encouraged Maya Deren to undertake a film that in many ways is similar: Meshes of the Afternoon , which bears the title card "Hollywood 1943." Meshes visualizes the feelings and thoughts of a young woman (played stunningly by Deren herself) who at a turning point in her life and relationships pursues a mysterious nun with a mirror hiding her face (played by the New Mexico painter Florence Pierce; Fig. 83). We see the protagonist as three different women performing the same

everyday actions, and each time a sequence recurs, we become more sensitive to the mythic/ritual aspects of these simple deeds and objects. The three women differ in essential ways: one is so light that she seems to float upstairs, another is so heavy that she moves in lugubrious slow motion, and the third is so inept or imbalanced that she staggers intermittently.

While Meshes uses the camera tricks, dramatic lighting, and symbolic gestures of the European avant-garde and refers overtly to the surrealist Freudianism of films like Cocteau's Blood of a Poet and Dalí-Buñuel's Chien Andalou , Deren and Hammid manage to surpass their European prototypes in both technical excellence (their camerawork and editing are brilliant) and conceptual ingenuity, for Deren achieves true ambiguity and moodiness that continually suggest more—approximating Jung's quasi-mystical theory of the archetype rather than the simplistic Freudian symbolism of the surrealists.

After finishing Meshes , Deren returned to New York, where she created two films, At Land and Ritual in Transfigured Time , that form a trilogy with Meshes . She also made three other films, wrote numerous articles about film as an art form, toured tirelessly with her films, and helped to establish a circuit of distribution and exhibition for experimental short films.

Deren's work in Los Angeles had dynamic repercussions, for she encouraged several young men there, including Kenneth Anger, Curtis Harrington, and Gregory Markopoulos, who had been toying with "amateur" film and vaguely hoping for careers as directors in Hollywood, to begin making 16mm experimental films that were artworks in and of themselves. Anger's Fireworks (1947), Harrington's Fragment of Seeking (1946) and On the Edge (1949), and Markopoulos's Psyche (1948) all treated aspects of homosexuality in a frank yet lyrical fashion that exposed experiences of both terror and beauty. In the manner of Maya Deren, they all made imaginative use of cinematic devices to suggest a surreal dream world. And each man played the protagonist in his own "psychodramas," as this type of film came to be known.

All three filmmakers enjoyed international acclaim for their uncompromising, experimental work—an alternative version of "Hollywood" that was poetic and imaginative, honest and uncensored. Anger and Markopoulos would both make experimental film their life's work, but after a half-dozen successful shorts, Curtis Harrington became an independent Hollywood feature director with such distinguished credits as Night Tide, Games , and What's the Matter with Helen? Harrington's features brought to seemingly conventional genre films touches of surrealistic irony and bizarre juxtaposition—astonishing, vivid images that confront a mass audience with an uncanny, unexpected mirror image of themselves rather than superheroes, ravishing beauties, and grotesque villains.

One of the finest artistic achievements of modernist California, the cultivation of the preeminent school of "visual music," developed at the same time as live-action experi-

mental film. Indeed, visual music has a history that parallels that of cinema itself. For centuries artists and philosophers theorized that there should be a visual art form as subtle, supple, and dynamic as auditory music—an abstract art form, since auditory music is basically an art of abstract sounds. As early as 1730, the Jesuit priest Father Louis-Bertrand Castel invented an Ocular Harpsichord, which linked each note on the keyboard with a corresponding flash of colored light.[13] Many other mechanical light-projection inventions followed, but none could capture the nuanced fluidity of auditory music, since light cannot be modulated as easily as "air." The best instrument for modulating light took the form of the motion picture projector.

In any case, the movie industry provided a major reason for the growth and flourishing of visual music in Los Angeles. Movie musicals, especially those lavish semi-abstract Busby Berkeley numbers,[14] are a form of visual music, and the industry supplies ready access to technology. Furthermore, during the 1930s and 1940s a plethora of talent passed through or settled in Los Angeles in hopes of gleaning some benefits, contacts, or fulfillment from the boomtown. The rise of fascism in Europe quickened the influx of artists.

It may be hard for us to imagine the immigrant artist community of those decades. In March 1939 Paul Hindemith played as guest violist with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra under the baton of regular conductor Otto Klemperer. After the performance a lively crowd assembled backstage, including such famous figures as the movie director William Dieterle, the composers Ernst Toch and Arnold Schoenberg, the novelists Vicki Baum and Thomas Mann, and a dozen more, all merrily chatting in German. Suddenly Klemperer cried out (in German), "Are we, then, actually in Berlin, not in Hollywood?" Also present at this historic occasion was one of Hindemith's best friends, Oskar Fischinger (Fig. 84), the foremost influence on the development of visual music in California.

Born in Germany in 1900, Fischinger began making abstract films in Frankfurt in 1922, and by 1926 he was performing multiple-projection "light shows" in his Munich studio.[15] In the late 1920s, he began sychronizing nonobjective imagery to popular records; the resulting films were shown in theaters as advertisements for the records—the first music videos. After a successful series of sixteen of these black-and-white Studies (some were screened in the United States as well as in Japan and South America), he made the first full-spectrum color films in Europe: Circles (1933) and Composition in Blue (1935). At the same time, he also produced the famous walking cigarette commercial, which was copied internationally. He was able to immigrate to Hollywood in 1936 under contract to Paramount (for Allegretto , released in 1943) and in 1937 produced for MGM the abstract film An Optical Poem , which was distributed as a short in theaters everywhere. In fall of 1938, Fischinger was hired to design and animate portions of Disney's Fantasia , and his films were screened weekly for a year to the entire staff of Disney Studios, where they made a lasting impression.[16] Although Fischinger quit Disney after a year because staff committees changed all his designs and ideas, his touch

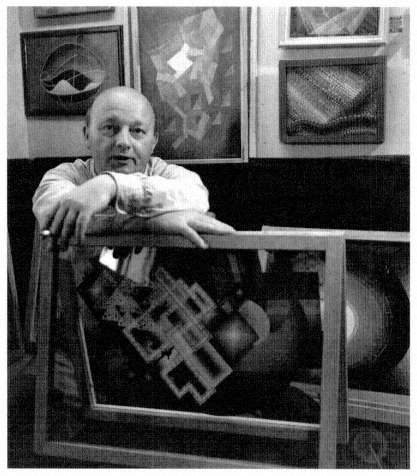

Figure 84

Oskar Fischinger with the original paintings for the film

Motion Painting No. 1 , 1949. Photograph by William G. Hewitt, Jr.

is still visible in the opening Bach episode of Fantasia . Examples of Fischinger's work were thus shown to a broad American public.

Fischinger himself, however, found it difficult to work in the factory environment of the studio, and he encountered even more difficulty raising money for independent film projects, so he turned increasingly to easel painting as an outlet for his creative energy. In Germany he had purposely refused to paint since he believed that kinetic abstraction—visual music—would be the art of the future. But he did not begin oil painting as a novice, for he had made thousands of paintings as the basis of his anima-

tion films, many of which prefigure the serial work of artists like Josef Albers and Frank Stella. Fischinger also knew many painters from Germany—including great artists like László Moholy-Nagy and Lyonel Feininger and the not-so-great artist Rudolf Bauer. (The art dealer Karl Nierendorf, a good friend of Fischinger's, took him to visit the pompous Batter's studio, named Das Geistreich, "Realm of the Spirit," near Berlin, and they shared a good laugh on the way home.)

In 1938 Fischinger was invited to New York for two one-man shows of his intricate, layered oil paintings (at the Boyer and Nierendorf galleries) and a film screening at the Fifth Avenue Playhouse. In New York he met Baroness Hilla Rebay yon Ehrenwiesen, curator of the Solomon Guggenheim Foundation and founder of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now the Guggenheim Museum). During the difficult war years (Fischinger was still an "enemy alien" and so could not work in any media-related job) Rebay helped support Fischinger both by giving him grants and by purchasing his films. Screened regularly at the museum, these films were seen by a whole range of future New York School abstract painters—not least among them Jackson Pollock, who was employed there. A number of Fischinger's canvases were also exhibited at the museum. But his relationship with Rebay was tortured, to say the least, and he suffered mental anguish at her teasing, tantrums, and insults as often as he gained peace enough to work.[17]

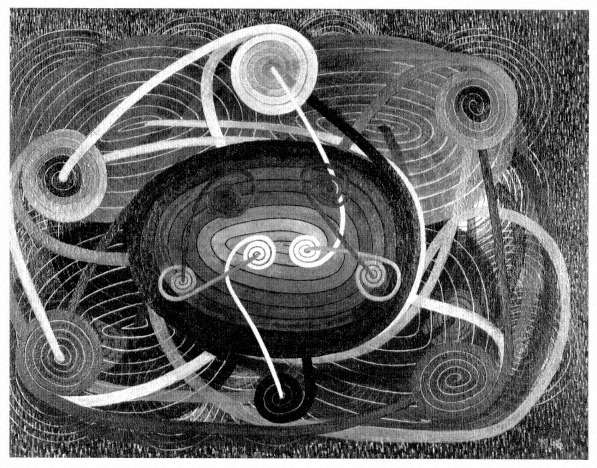

On his meager income Fischinger finished two more film masterpieces: Radio Dynamics and Motion Painting No. 1 (Fig. 85). Radio Dynamics , an intentionally silent film meant as a contemplative, meditational aid, contains both hypnotically pulsating mandalas and brilliantly flickering single-frame images. As the title implies, Motion Painting records the growth of a specific oil painting, with one frame of film shot each time a brush stroke was made. The film is distinguished not only for this novel idea but also for the intrinsic fascination of the developing design, which moves through soft amorphous shapes to hard-edge geometric forms and culminates in a serene, irresistible mandala. Although Motion Painting won the grand prize at the International Experimental Film Festival at Brussels in 1949, Rebay failed to understand its dynamic structure or even its innovative documentation of a painter's working process and gesture. She simply hated the film and refused to extend Fischinger any further aid. Discouraged, and unable to obtain financial backing from other sources, Fischinger withdrew from active film production.

As much as Fischinger was harassed and denigrated by Rebay's tirades, he was sustained and encouraged by the remarkable Galka Scheyer, who allowed him to study the superb Klees, Kandinskys, and other abstract paintings that passed through her hands—and made sure he had full access to other caches of abstract art in Los Angeles: the magnificent collection of the Arensbergs (now in Philadelphia) as well as those of Ruth Maitland, Merle Armitage, Marjorie Eaton, and others. She also sent younger artists to visit Fischinger, including the fledgling John Cage, who credits Fischinger with crucial formative influence on his conceptual music theory.[18]

Figure 85

Oskar Fischinger, Motion Painting No. 1 , 1947.

Fischinger's films also screened regularly in Los Angeles—at the Art Center School, Otis Art Institute, and Chouinard Art Institute, the three best art colleges in the area, where Lorser Feitelson, Helen Lundeberg, Helen Wurdeman, the ceramist Al King, and the photographer Frank Judson sponsored Fischinger and became devoted friends.[19] Between 1946 and 1950 Al King also screened Fischinger's films at the California Color Society, where other painters fell under Fischinger's spell, among them the movie star Harold Lloyd, whose 1953 exhibition of "Landscapades" at the Frank Perls Gallery showed a marked turn toward abstraction.[20] Fischinger also exhibited at the Stendahl Art Galleries and the American Contemporary Gallery, among others.

At the Stendahl show in the fall of 1939, the Whitney brothers encountered Fischinger's work.[21] James (then eighteen) and John (twenty-two) had just returned from Europe, where they were extending their studies in painting and music, respectively. John (like John Cage) had attended the Claremont Colleges, and in Paris John Whitney had met René Leibowitz, who introduced him to the twelve-tone principles of Arnold Schoenberg (who, ironically, had been teaching at the University of Southern California since 1934). Although John Whitney never studied directly with Schoenberg himself, the composer's progressive theories fascinated both the brothers, who in their first eight films offered visual equivalents of his tone rows and permutations. Their first four films, shot in 8mm, were made in their studio in Pasadena from 1940 to 1942. These lovely silent works are astonishingly accomplished for first films by young men. They have the vigor and delicacy of fine chamber music, and perhaps their maturity stems in part from the Schoenbergian rigor they chose for their exemplar and process.

Although the brothers had been inspired by Fischinger to make films, they were somewhat bothered by the tight relationship between known music and the visual imagery in Fischinger's films—something that bothered Fischinger as well. His early films, from the 1920s, were either silent or had new music composed for them. He became involved with tight synchronization partly because of his commercial ties with record advertising and partly because he found that audiences would more easily accept abstract visual art if it were linked to known music (abstract auditory art) they already approved of. After the international success of Fischinger's synchronized films producers, distributors, and audiences demanded more. But Fischinger longed to have his visual music appreciated as art separate from (albeit equivalent to) auditory music, and from 1941 to 1943, worked on an intentionally silent masterpiece, Radio Dynamics . Moreover, although Rebay's commission for the 1947 Motion Painting specified that it should be synchronized with Bach's Brandenburg Concerto no. 3, Fischinger constructed the visual imagery as a loose parallel, with no note-for-note correspondence, and often screened the film as a silent movie. It is unfortunate and ironic that the Whitney brothers were too polite to discuss synchronization with Fischinger, who might have found such an aesthetic debate beneficial and encouraging.

The Whitney brothers proved with their 8mm Variations that they could compose successful silent visual music, and in the last film of this series, Variations on a Circle (1942), James Whitney showed that he could create a little masterpiece comparable to Radio Dynamics .

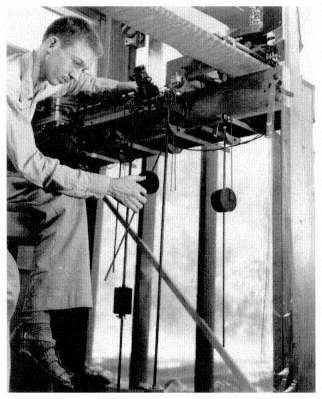

John Whitney's memorable contact with René Leibowitz made him long to compose auditory music as novel as their visual imagery. He invented a system of pendulums that could be calibrated to draw directly on the soundtrack area of the film precise oscillations that would play back as pure tones (Fig. 86). With this system the Whitneys could compose music and abstract visual imagery simultaneously. During 1943 and 1944, John made Film Exercise No. 1 and Film Exercise No. 5 , while James made Film Exercises Nos. 2 and 3 and No. 4 , which combined pendulum music with geometric

Figure 86

James Whitney composing music with the Sound

Pendulum system. Photograph by Lou Jacobs, Jr.

shapes cut out of paper matte boards so that the camera could film, from the resultant openings, pure light rather than reflections of a drawn artwork. The effect was shocking and "electrifying": the visual imagery had the eerie glow of neon lights, and the sound introduced many ears to the pure sine waves, aggressive tonal attacks, and the extravagant range of sound placements and seamless glissandi that a decade later would become familiar as electronic music. With these pioneer electronic sound scores of their own composition, they also won a first prize at the Brussels Festival in 1949.

While working on the Exercises , the brothers visited the Frank Lloyd Wright buildings designed for Aline Barnsdall on Olive Hill in Hollywood. The photographer Edmund Teske, an artist-in-residence at a guest cottage there, had already met them at a screening in the American Contemporary Gallery, and he encouraged them to join him as artists-in-residence, since other cottages were available. In this central location,

they quickly became artistic celebrities, since the buildings attracted such neighbors as Man Ray and the sculptor Tony Smith, who instantly recognized the extraordinary quality of the young men's work and became frequent visitors and friends, as well as such casual, curious visitors as Bertolt Brecht. James Whitney's and Teske's fascination with spiritual disciplines brought them to the Vedanta Center, where they became friends with the British expatriates Christopher Isherwood, Gerald Heard, and Aldous Huxley. Their Olive Hill salon also served as a screening place for such experimental filmmakers as Maya Deren, Curtis Harrington, and Kenneth Anger.

In 1944, with the Exercises completed, James traveled to New York to see if Baroness Rebay might also include their work in the Guggenheim collection and possibly fund a new film. Rebay did purchase prints of the Exercises , and both the 8mm Variations and the 16mm Exercises were screened several times in New York during 1944 and early 1945. James's first audience included such old friends as Tony Smith, John Cage, and Sidney and Harriet Janis, as well as such diverse celebrities as Tennessee Williams and Marcel Duchamp—luckily, since as soon as Film Exercise No. 1 began, the Baroness flew from the room screaming "What's wrong with the projector?" and forced the projectionist to shut off the film, and the showing resumed only when the distinguished audience intervened. Jackson Pollock (a drinking buddy of Tony Smith's) was at this screening, and the Guggenheim prints of the Whitney films were shown regularly at the museum thereafter, so they were, like Fischinger's films, accessible to the future New York School abstract painters, who would have appreciated their aggressive colors and action as well as their uncompromising sound.

Although Baroness Rebay offered to continue the Whitneys' stipend, they found her manner and aesthetic opinions oppressive and declined it. Charles Dockum, on the other hand, like Fischinger, had no recourse but to endure Rebay's foibles, since he absolutely needed the Guggenheim support to continue his work. Born in Texas in 1904, Dockum was forced to move to Prescott, Arizona, after college, because of his delicate health. There, in 1935, he constructed his first small color organ, a seminal version of his later MobilColor Projectors. And there he met (through the photographer Fred Sommer) the man who became a lifelong friend and artistic influence: the Ukrainian-born painter and sculptor Peter Krasnow, who had lived in Los Angeles since 1922. Krasnow introduced Dockum to Galka Scheyer after Dockum moved to Los Angeles in 1940. With an improved MobilColor Projector, Dockum performed at the California Institute of Technology and the Pasadena Playhouse (where the Whitney brothers and Sara Kathryn Arledge met him), as well as at the Art Center School and the University of Southern California, where Frank Judson, a friend of Krasnow's, was head of the Cinema Department (where Gregory Markopoulos and Curtis Harrington studied).

In February 1942 Dockum wrote the Guggenheim Foundation, requesting a grant to prepare a more complex and effective MobilColor Projector.[22] At first Rebay was reluctant. Thomas Wilfred, an older and more established color-organ artist, had attempted to interest her in one of his instruments, but she had not liked it because she

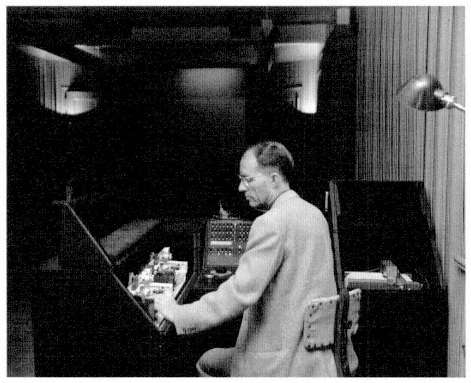

Figure 87

Charles Dockum playing his Guggenheim MobilColor Projector for the last time,

in 1953, at the Guggenheim Museum of Non-Objective Painting, New York.

felt the soft polymorphous flow of Wilfred's subtly nuanced imagery was not precise and controlled like the hard-edge geometric paintings of her favorite painter, Rudolf Bauer. Although Wilfred explained that he did carefully design the imagery and could program both his clavilux projectors and his internal projection Lumia boxes to repeat exact compositions, Rebay wanted none of his sensuous delicacy. Fortunately for Dockum, Rebay's arch-rival, the Museum of Modern Art, purchased one of Wilfred's major Lumia compositions for permanent display in their galleries, thus piquing the baroness's urge to possess a color organ. She paid for Dockum to bring his MobilColor Projector to New York, where he spent the month of June 1942. Rebay reported that an audience of "expert" painters and filmmakers was "enchanted" by one of his performances—so again Dockum's work may have been seen by Jackson Pollock and the New York School.

Rebay awarded Dockum a stipend to build a MobilColor Projector for permanent installation at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (Fig. 87). But with her he fell

into the same depressing turmoil Fischinger and the Whitneys had experienced. She asked him several times to spy on Fischinger to find out if he was really working on the Bach Brandenburg Concerto project. The two artists became friends, although Fischinger adamantly refused to let Dockum into his studio. (He was in fact having trouble with the Bach project and was not working on it every day.) In September 1942, when Dockum tried to interest Rebay in the abstract sculpture of Peter Krasnow, she haughtily replied that she and "several very great artists" did not like his work at all. She informed him that sculpture was a second-rate art form anyway, and he should not really associate with an "average" person like Krasnow, but rather strive to "impress a master like Bauer."

Rebay also monopolized much of Dockum's time, having him write letters and perform other useless tasks. She had him spend considerable time drawing up elaborate plans for Frank Lloyd Wright to incorporate into the new museum building, but Dockum's suggestions were never used. Fischinger had similarly been charged with designing film projection rooms and studio spaces where animators could work, but none were ever built; Fischinger's demand for projection onto an overhead dome, however, contributed to the final shape of the museum building, even though fire regulations prohibited the ground-floor horizontal projection booth that would have allowed films to be screened on the dome.

Dockum's Guggenheim episode has a more tragic ending than that of either the Whitneys or Fischinger. Dockum spent the ten prime creative years of his life constructing the Guggnheim MobilColor Projector and composing a series of pieces to be played on it. When the museum directors found that the instrument would not really play continuously without supervision, they determined that it could not be exhibited and should be dismantled. Some of the lighting elements were used for track lighting in the galleries; other parts were donated to Yale University. The instrument legally belonged to them, so Dockum could do nothing—but his compositions, created specifically for that mechanism, could be played on no other and thus were useless, "destroyed."

Ted Nemeth and Mary Ellen Bute, who had produced a series of abstract films in New York beginning in the mid-1930s, attempted to film the Dockum compositions once before the instrument was dismantled. Part of Dockum's artistry, his very reason for working with a color organ rather than film, involved the subtle modulation of color from nearly invisible hints to blinding, saturated intensities; he also layered colors, playing upon the resulting push-pull effects and optical mixtures. These subtle details could hardly be captured on film, especially since the light needed for a good film exposure can exceed what seems dazzlingly saturated during a live performance in a darkened room because of the complicity of the spectator's eye. The Bute-Nemeth documentary, even if much of the color and nuance are lost, nonetheless shows that Dockum's MobilColor compositions involved simultaneous movement in three different directions, and an effective precision in the layering.

Back in his studio in Altadena (the suburb of Los Angeles where James Whitney was born), Dockum set about building another MobilColor Projector, but at the time of his death in 1977, he had composed only three pieces, a total of some fifteen minutes' playing time, for his new instrument. The serene luminous beauty of these works cannot be seen without a twinge of regret for the art that the art world fails to support.

The end of World War II brought a flurry of activity to the experimental film and visual music scene—so much so that an official MGM Studio memo to Jean Hersholt, dated May 14, 1946, lists three venues for art cinema in Los Angeles: the American Contemporary Gallery, the Great Film Society, and Paul Ballard's Film Society.[23] Within a year there would be two more—Creative Film Associates (run by Curtis Harrington and Kenneth Anger) and the Experimental Film Society (where Maya Deren and Sasha Hammid appeared for a screening of their films April 13, 1947)—and then three more: the Society of Cinema Arts (1948), Bob Chatterton's Film Society, and Raymond Rohauer's Film Society, which in 1950 would take over the Coronet Theatre (where Stan Brakhage, later famous as an experimental filmmaker, worked as projectionist) and in 1957 the Riviera/Capri Theatre, both as cinemas showing a repertory of experimental and art films.

The first experimental film made in San Francisco was probably The Potted Psalm , a surrealistic comedy made in collaboration by two writers, James Broughton and Sidney Peterson, who in 1946 were suffering from writer's block and turned to cinema as a recourse.[24] Their film premiered as the finale to Frank Stauffacher's first experimental film series at the San Francisco Museum of Art.

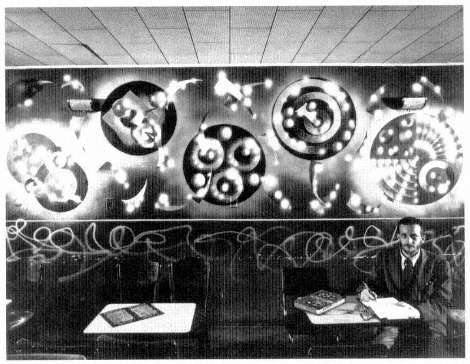

Stauffacher's series of Art in Cinema festivals began in October 1946 and continued through a sixth series, in 1950.[25] When the initial series brought the Whitney brothers and Oskar Fischinger to San Francisco, two young painters, Jordan Belson and Harry Smith, were inspired to begin abstract filmmaking, and their subsequent distinguished careers helped to confirm the existence of a California school of visual music (which itself engendered a number of minor filmmakers such as Robert Howard, Hal McCormick, Elwood Decker, Ralph Luce, Leonard Tregillus, Dorsey Alexander, Martin Metal, Denver Sutton, and Curtis Opliger). Stauffacher had sent Harry Smith to Los Angeles to talk Fischinger and the Whitneys into coming to San Francisco for the first Art in Cinema, and Smith was so smitten with their work that he began to make his own. He drew directly on film stock since he did not have a camera, animation stand, or optical printer. His first five films, all hand-drawn (they include some footage Smith shot with Hy Hirsh's camera moving quickly past lights at nighttime), were closely allied to the new bop music; they premiered at subsequent Art in Cinema festivals, accompanied by live jazz ensembles. Smith painted large abstract murals at the nightclub Bop City (Fig. 88) and screened his film there as a "light show" accompanying such musicians as Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonius Monk. Jordan Belson has withdrawn his earliest films from the 1940s, which were greatly admired at that time;

Figure 88

Harry Smith, in front of his abstract murals at Bop City jazz nightclub, San

Francisco, ca. 1949. Photograph by Hy Hirsh, courtesy Jordan Belson.

Fischinger, after seeing his first film, Transmutation , at Art in Cinema, recommended Belson for a Guggenheim Fellowship. After his spectacular Vortex Concerts of the late 1950s, which sychronized electronic music with abstract imagery projected on a planetarium dome, and after seeing some of Wilfred's sensuous Lumia compositions, Belson became more sophisticated in his films, which as a result better expressed his spiritual aims.

Similarly, Maya Deren's trilogy, shown at Art in Cinema, inspired a raft of new film psychodramas. In Northern California, Sidney Peterson and James Broughton continued their filmmaking separately and began to offer an experimental filmmaking course at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Art Institute). James Broughton's Mother's Day (1948) was particularly successful, capturing the ironic ambiguity of the adult's nostalgic remembrance of his childhood and the sexual-social politics foisted upon children that mark them for life.[26] Hy Hirsh worked on some psychodramas (Horror Dream and Clinic of Stumble , both in collaboration with Sidney

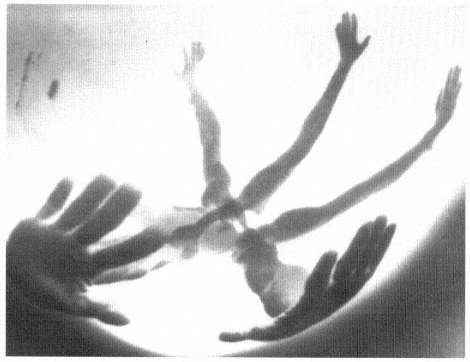

Figure 89

Sara Kathryn Arledge's Introspection (1941 and 1946).

Peterson) before turning to visual music after 1950, and Chester Kessler prepared a remarkable quasi-animated version of Kenneth Patchen's Journal of Albion Moonlight , entitled Plague Summer . Nor were all the new films psychodramas. Frank Stauffacher, for example, produced three fine lyrical landscape films (or city symphonies, as such films were called by the German experimental filmmaker Walther Ruttmann): Sausalito, Zig Zag , and Notes on the Port of St. Francis . In Southern California, in addition to work by Kenneth Anger, Curtis Harrington, and Gregory Markopoulos, the painter Joseph Vogel in 1947 made All the News and House of Cards , for which the Whitney brothers optically printed his paintings as the background for a "psychodancer."

In 1941 in Pasadena (where the Whitney brothers worked) Sara Kathryn Arledge had begun an abstract dance film, Introspection (Fig. 89), which involved dancers in black tights with only one body part in color so that against a black background it seemed as if arms or torsos or clusters of superimposed legs had taken on a life of their own and could dance unconstrained by gravity. Unfortunately, her lead dancer, Jim

Mitchell, was drafted into World War II, so she abandoned the project. Living in San Francisco in 1947, Arledge was reinspired by Art in Cinema, and she finished the film, which premiered May 2, 1947, during the second series. In the summer of 1947 she also published a key essay, "The Experimental Film: A New Art in Transition," which treats Fischinger, the Whitney brothers, Maya Deren, and Charles Dockum in the context of the earlier avant-garde film.[27] The program notes to the first series of Art in Cinema, including invaluable statements by Deren, Fischinger, and the Whitneys, were also published as a catalogue by the San Francisco Museum of Art in 1947.[28] In the same year, the film historian Lewis Jacobs also published "Experimental Cinema in America" in the new journal Hollywood Quarterly (now Film Quarterly ).[29] a new American experimental film movement, heavily based in California, had come of age and would flourish during the coming decades in the work of Christopher Maclaine, Larry Jordan, Bruce Conner, Bruce Baillie and Canyon Cinema, Gunvor Nelson, Robert Nelson, Chick Strand, Pat O'Neill, and many others.

California experimental film and visual music clearly inspired new underground, independent, personal, and/or avant-garde work in film in both New York and Europe. But another influence, which I have already alluded to, may link New York abstract expressionist gestural painting to Southern California. Jackson Pollock first studied art at Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, 1928-30. His teacher there, Frederick Schwankovsky, had a powerful mystically oriented personality, which displayed itself in frequent lectures, radio broadcasts, newspaper articles, and exhibitions in Los Angeles.[30]

Schwankovsky's devotion to Theosophy and Krishnamurti formed an integral part of his artwork and his teaching. In his brilliant painting Modern Music (Fig. 90), from about 1914, we can see a relationship with the hermetic color-music theories of other theosophically inspired painters (e.g., František Kupka, in his Piano Keys—Lake , 1909). But even a novice, with no knowledge of that tradition—like Pollock, perhaps, when he saw the painting (it remained in Schwankovsky's possession until 1940)—can appreciate the sense of dynamic color expressing inner perceptions and emotions. The woman playing the piano while pentangles of color arise from the keys might well be Schwankovsky's wife, Nelly, who would play certain notes on the piano while "Schwanny" (as Pollock affectionately called him) would paint the corresponding colors, a living visual music performance.

Schwankovsky published a booklet, which he distributed to his students, explaining the mystical qualities of colors and the correspondences between colors, musical notes, emotional propensities, and astrological signs.[31] He generously introduced his students to as much mystical theory as possible: he drove Pollock to Ojai to hear Krishnamurti speak and took groups of students to visit Manly P. Hall's Philosophical Research Society library of rare hermetic incunabula and grimoires. At the same time, Schwankovsky introduced his students to a variety of art techniques, encouraging experiments mixing oils, water, and alcohol. And in his scenic design classes, which built sets for local theatrical productions, he taught the students (including Pollock) to lay canvas on

Figure 90

Frederick Schwankovsky, Modern Music ,

ca. 1914. Oil on canvas, 26 × 20¼ in. Laguna Art Museum,

gift of the artist, 1940.

the ground and dance around it, dripping and splattering paint to create starscapes and tropical lianas.

What Pollock learned from Schwankovsky in California made him see things differently in New York. During the early 1930s, while Pollock studied at the Art Students League, he often went to visit Thomas Wilfred's studio (named Institute of Light), where he sat for hours watching the gradual trajectories of colored light in Wilfred's Lumia compositions, swinging his head around to follow as if he recognized the tra-

jectories as Wilfred's gestures. In 1943, when he was working for Baroness Rebay at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, he saw the Fischinger films, which were screened regularly, and probably Dockum's MobilColor Projections as well. When James Whitney had screenings at the museum in late 1944 and early 1945, Tony Smith (who before leaving Los Angeles had done some remarkable poured and dripped paintings, possibly in rapport with Knud Merrild's flux paintings) took his new buddy Pollock to see them. These repeated, reinforcing exposures to the kinetic abstraction of visual music (mostly from California), in which gestures of light splash, ooze, and layer across the large screen, must have contributed to Jackson Pollock's crucial change from semirepresentational easel painting to large nonobjective canvases created by expressionistic gestures of the painter.

California visual music influenced a number of other artists. Oskar Fischinger, for example, inspired the sculptor Harry Bertoia to make sounding brasses—abstract sculptures with movable parts that create musical sounds when they touch—which he would assemble in a large space and play symphonically by dancing among them to set off various harmonious patterns. And visual music covertly reached a mass audience in the form of United Productions of America (UPA) cartoons.[32] UPA was founded in the mid-1940s largely by artists who had worked for Disney on Fantasia and thus had been "indoctrinated" by Fischinger's work at the studio. Some of these artists shared Fischinger's interest in abstract painting—Herb Klynn, Jules Engel, and Fischinger, for example, had a three-man show together at the American Contemporary Gallery in 1947. The artists formed UPA as a cooperative animation studio with the express purpose of making films that would combine modern art, contemporary literature, and new music. In 1948 they received their first Academy Award nomination, and in 1950, when Gerald McBoing Boing , with art direction by Jules Engel, won an Academy Award, UPA was world famous for modernist animation presented in a visual and auditory style that expressed the subject matter at hand, whether it was children's stories or classic literature (The Tell-Tale Heart ), social satire ( The Jaywalker, Fudged Budget ), contemporary art (two films about abstract expressionism, Blues Pattern and Performing Painter , animated by John Whitney in collaboration with Fred Crippen and the Oscar winner Ernie Pintoff), or biographies of famous artists (Sharaku, Raoul Duly , and Henri Rousseau , all written by Sidney Peterson). Much of the worldwide flourishing of artistic animation in the 1950s and 1960s owes a debt to the modernist strivings of UPA, which in turn derived from visual music and film-as-an-art in California before 1950.