INTRODUCTION

Paul J. Karlstrom

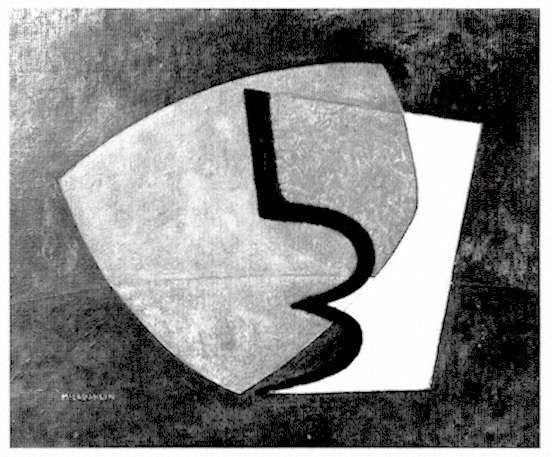

California, from an eastern perspective, has generally been seen as another country on the far edge of America, only tenuously attached to what is understood as Western civilization. Carey McWilliams's famous characterization of Southern California as "an island on the land" captures some of this psychological and cultural distance.[1] Identified almost exclusively with Hollywood and popular culture, California has even been denied a meaningful relationship to twentieth-century modernism. Viewed through a mid-century critical lens, earlier California art may indeed appear to have little significance in connection with the prevalent European and East Coast understanding of modernism. Carefully observed, however, twentieth-century California may well offer the most useful paradigm of a "postmodernist" culture reflecting contemporary experience, desire, and fantasy, both in pictorial images (Fig. 1) and in the built environment (Fig. 2). This collection of essays represents an effort to deal with the art of California in its own aesthetic and sociological terms.

The issue of regionalism in American art is central to this study. How can we build a cultural portrait of California that reveals both what is distinctive about it and what links it to the national culture? Some essays, such as those by Brain Dijkstra, William Moritz, Margarita Nieto, David Gebhard, and Therese Thau Heyman, elucidate the unusually fecund environment for artists in California, one that invites and clearly warrants scholarly attention. Others, among them Peter Selz, Susan M. Anderson, and Susan Landauer, treat their subjects as parts of a larger whole, placing California developments in a national and even international setting.

These essays, whatever their differences, accept the role of geography in forming local culture and that of regionalism in determining how art and artists are perceived and how their historical significance is assessed. The eastern perspective plays a large part in the story. It was succinctly stated by the leading critic of his day, Edmund Wilson, who noted the West Coast's deficiencies of climate and landscape and its

Figure 1

Knud Merrild, American Beauty, or the Movie Star , 1928. Oil and

collage, 19 × 16 in. The Oakland Museum, Oakland, California, gift of Else Merrild.

remoteness from the East and . . . farther remoteness from Europe. New York has its own insubstantiality that is due to the impermanence of its people, of its business, of its thoughts; but all the wires of our western civilization are buzzing and crossing here. California looks away from Europe, and out upon a wider ocean and an Orient with which, for white Americans, the cultural communication is slight.[2]

In light of such a dismissal, it is not surprising to find regionalism a unifying element in a collection of essays on the art and culture of an area far from such established centers of creative activity as Paris and New York. Implicit in this discussion is the concept of a new colonialism and the way California artists came to see themselves in

Figure 2

Norman Marsh and C. H. Russell, Arcades at Venice, California, ca. 1906.

California Historical Society, Title Insurance and Trust Photo Collection,

Department of Special Collections, University of Southern California Library (neg. 2067).

relationship to ideas, individuals, and events associated with the centers. Accordingly, each author has taken these issues into account. The essays in this volume concentrate on "progressive" developments, thereby narrowing the selection of artists, works, and events. At least by the end of the period under consideration the narrative focuses on the counterculture—but more than that, on an alternative culture that transforms the ideas and examples of modernism according to regional imperatives. In so doing, it provides a model for late-twentieth-century self-discovery.

Several related themes, reflected throughout the book, suggest a distinguishing cultural zeitgeist. Chief among these is a sense of distance and the consequent need to reinvent traditions for a new landscape and society. The historian Kevin Starr, in his series Americans and the California Dream , discusses this need as a powerful formative force. For him California's story is an imaginative journey to identity—a fair description of the artistic activity of the period. Casting a broader net, Michael Kammen offers similar insights in his Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture . Young societies invent traditions, the symbolic evidence of a past, not only to give meaning to the present, but also to foster individual and community identity. Although this dynamic is not restricted to California, circumstances in the state exaggerated it and thus produced here a distinct, parallel American culture.[3]

Dore Ashton has pointed out that the critical and historical effort to locate and explain modernism theoretically is a fairly recent phenomenon.[4] To give art a modern identity separate from that of the past, critics have aligned it with literary criticism and philosophy. But in the hands of such intellectuals as Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg what were once fairly simple ideas that could be grasped "intuitively" have been turned into complex and, ironically, delimited theoretical systems. In the Greenbergian view, for example, unity and purity through and in abstraction became primary—if not exclusive—modernist goals. According to one observer, Greenberg's writings actually "constitute the locus of present modernism in the visual arts."[5]

Before World War II theory played a far less prominent role; critics discussed modernism as the "art of the new," setting up a fairly clear antagonism between what looked forward and what clung to the past. For many, a machine aesthetic expressed the crucial link between art and scientific progress. For some, nonobjectivity became the issue. So Henry McBride wrote in 1930, "There are other attributes to modern art but the ability to feel the abstract is the real test."[6] Without necessarily embracing abstraction, California critics such as Alfred Frankenstein, Arthur Millier, Jehanne Bietry Salinger, Sonia Wolfson, Grace Clements, Merle Armitage, Florence Lehre, and Porter Garnett thought and wrote of art and artists as progressive and conservative, one camp open and receptive, the other closed and doctrinaire.[7]

The debate was seldom more complex until critics developed their responses to abstract expressionism in New York in 1945. Up to that point, modernism embraced a fairly wide variety of styles and expressions originating in different parts of the country But as abstract expressionist art and theory came into prominence, New York assumed

Figure 3

John McLaughlin, Untitled , 1949. Oil on Masonite,

19 ½ × 23 ½ in. Tobey C. Moss Gallery, Los Angeles.

the pivotal role it holds to this day. This situation is relevant to our subject, the preceding half-century, because the expanding field of art history at American universities in the 1960s in effect simplified the phenomenon of modern art and located it almost exclusively in New York. In the process, regional art and art history were, if not ignored, relegated to the margins. Among the casualties have been artists as original as Ben Berlin (Plate 1) and as profound as John McLaughlin, surely one of this country's most thoughtful geometric abstractionists (Fig. 3).

The task of locating and describing modernism in California is further complicated by uncharted terrain and an incomplete cast of characters. An intriguing case in point is the little-known modernist Edward Hagedorn, born in San Francisco in 1902. Hage-

Figure 4

Louis Siegriest, Oakland Quarry , 1920. Oil on cardboard, 12 × 16 ¼ in.

The Oakland Museum, Oakland, California,

gift of the artist. Photograph by M. Lee Fatherree.

dorn is among the handful of artists one could turn to for an "indigenous" expression of the modernist impulse. His images, in their sophisticated dialogue with European (notably German) modern art, rank among the more advanced work being done in California in the 1920s, work perhaps as "radical" as that of the highly touted Society of Six. Among the Six, only Louis Siegriest (Fig. 4) advanced beyond the hybrid fauve/ postimpressionist landscape paintings that then constituted progressive art in the Bay Area.[8] Judging from work that has only recently come to light, Hagedorn by 1926— the year of Galka Scheyer's exhibition of her Blue Four group at the Oakland Art Gallery—had absorbed not only the forms but also some of the spirit of German expressionism (Plate 2). Apparently this mainly self-taught artist enjoyed Scheyer's support and encouragement, even (according to one source) being invited to join Lyonel Feininger, Alexei Jawlensky, Wassily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee as a fifth member of the group.[9]

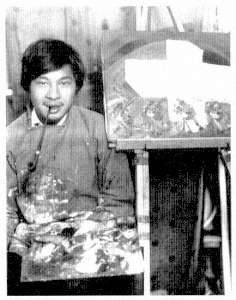

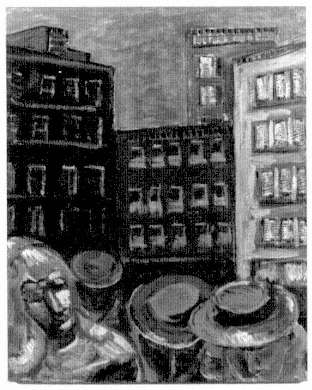

Many of Hagedorn's paintings effectively incorporate European modernist devices to serve individual expression, a noteworthy accomplishment, especially since Hagedorn—unlike Marsden Hartley and several other Americans who worked abroad, with whom he may productively be compared—had to satisfy himself with sources imported to his home state. Despite his remarkable "modernist" achievement, Hagedorn's name. insofar as I can determine, appears in none but the most recent literature on California art of the period. The same may be said of other accomplished progressives, for example, Yun Gee (Fig. 5) and Hisako Hibi, or even the surprising Swedish émigré Anders Aldrin (Fig. 6). In his relative anonymity Hagedorn is far from unique, either in California or elsewhere in the country.

Figure 5

Left : Yun Gee in Otis Oldfield's "Monkey

Block" studio, ca. 1925. Otis Oldfield papers

(on microfilm at Archives of American Art,

Smithsonian Institution). Photograph court-

esy of Jayne Blatchly Trust/ Otis Oldfield Estate.

Figure 6

Anders Aldrin, The Three Shoppers' (Downtown Los

Angeles ), 1935. Oil on canvas, 34 ¾ × 28 ¼ in. Anders

Aldrin Estate.

Among the few exceptions to this prevailing obscurity, Stanton Macdonald-Wright is easily the most prominent. His activities in Paris, notably the founding with Morgan Russell of synchromism, made him an acknowledged participant in the early story of international modernism. Back in Los Angeles, he assembled in 1920 an exhibition of American modernists at the Museum of History, Science and Art in Exposition Park. In the foreword to the exhibition brochure, in his characteristic style, he announces the arrival of modern art on the West Coast:

Today knowledge travels fast, and the idea, once engendered, speeds by electricity and steam, where once it trudged on foot, and finds fertile ground in the brains of thousands who, with one voice, proclaim its virility. Thus modern painting is not the isolated effort of a few men but another story added to the always growing edifice of art.

. . . now at last we present ourselves at that far-distant frontier of our native land.[10]

The correspondence of several Californians—among them Macdonald-Wright and the postsurrealists in Los Angeles, and artists such as Lucien Labaudt in San Francisco—reveals by this time both a vital interest in avant-garde art and a fairly sophisticated knowledge of its forms, issues, and movements in Europe. In fact, even in the early years California artists were less isolated from colleagues in New York and Europe than has been assumed. Many saw themselves involved in and contributing to the important work of establishing the new art. Annita Delano (Fig. 7), a founding member of the art faculty at the University of California at Los Angeles, wrote in 1929 to her friend Sonia Delaunay in Paris:

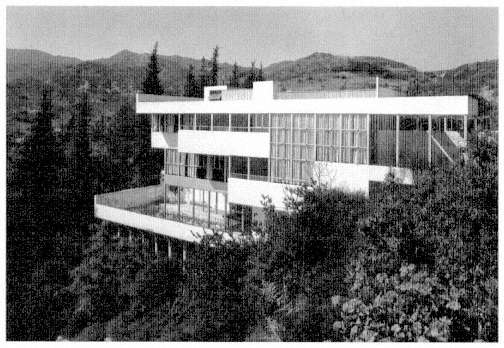

He [Stanton Macdonald-Wright] said to tell you he is hiding away in a cave in Santa Monica by the sea. I will tell you he's painting some splendid things. . . . in architecture here in Los Angeles there are a few leaders. Quite a number of buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright and some by his son. There are two men, R. M. Schindler and Richard Neutra who represent tendencies similar to Corbusier & Gropius. . . . So you see we have a miniature group pounding at the conservatives. The architectural clubs and the painters and sculptors are all debating about the modern trend—but they are so slow. I believe the greatest influence felt here is that of the Orient, and I suppose next to that the great raw country—so new, so provincial in some ways—but waking up.[11]

This letter is of particular interest in revealing the self-conception of at least some California artists and their understanding of the international modernist "project." There is a clear sense of participation and connectedness—of "being modern." Beyond that, Delano displays an awareness of the centrality of architecture and design, arguably California's greatest contribution to the unfolding of modernism in America (Fig. 8). In this correspondence, moreover, Delaunay describes her husband's current paintings

Figure 7

Annita Delano painting at Gallup, New

Mexico, 1934. Annita Delano papers, Archives of

American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Figure 8

Richard Neutra, Lovell House, Los Angeles, 1929. Photograph by Julius Shulman.

and encloses photographs of her own recent designs. Albert Barnes had introduced Delano to Henri Matisse; she became his close friend and regular visitor during the 1920s and 1930s. According to her own account, she would consult the French modernist master about color, taking careful notes that she would then use at a Parisian art supply store to obtain pigments unavailable to her at home. Apparently, she even transported several of Matisse's palettes back to Los Angeles.[12] It becomes clear in these and similar examples that despite California's seeming isolation, there were close contacts between Europe and the West Coast.

It may still be argued, however, that regional manifestations of modernist art are imitative rather than authentic, that the substance is lost in transmission over distance. If that is so, the conviction of Delano, Hagedorn, or even Feitelson and Macdonald-Wright (Plate 3) that they were participants in the "modern trend" may be regarded as self-delusionary. But typically and perhaps inevitably, California artists have "reconceptualized" European movements over distance and time. Because they viewed art and cultural achievements through a nostalgic haze, the result of a sense of loss (an important psychological component of the émigré experience), they were led to revisit and rework and thus recapture them. Under such circumstances, distance and isolation become virtues, the agents of transformative innovation rather than imitation.

All the essays in this volume ask what distinguishes the California experience— including art and culture—from that of the rest of the country. No author offers a conclusive answer. Thus the question lingers and attaches itself to notions of reinvention, self-discovery, appropriation, and creative legacy. These ideas are most fully developed in Richard Cándida Smith's adoption of Sabato Rodia into the modernist "fraternity"—an audacious but appropriate, even inspired, socio-aesthetic statement that Cándida Smith takes further by asserting that the challenge of modern life in California is different from that of most of the rest of the world. In such circumstances, the possibility existed for Rodia to re-create himself as a modern artist.

In another context, Margarita Nieto suggests that California modernism may, like Mexican art, incorporate sources from an "imagined, created" past. Similarly, David Gebhard argues that from an early date California developed an aberrant modernism responsive to local history and a set of particular social and environmental myths. In this respect, architecture's "game of images" presents an apt and revealing symbology of the dynamics and strategies involved in California's self-invention. One of the main points of Gray Brechin's chapter is the disjunction between San Francisco's historical self-image and the social and political realities Anton Refregier incorporated into his Rincon Annex murals. The modernist subtext to this stylistically conventional project (aside from its avant-garde politics) may be the open-ended possibilities and the struggle of conflicting identities in a fine arts forum. Finally, Therese Heyman looks at modernist photography in California in connection with a psychology of neglect. A medium without a history, photography embodies the ideas of invention and creation. Heyman recalls Edward Weston's belief that in an uprooted society the camera is a means of self-

development. Indeed, for the members of f.64 the power of photography as an instrument of personal expression was an article of faith, providing the road to self-discovery in an invigorating modernist context.

In 1963, just ten years after the House of Representatives debated the Rincon Annex murals, a French artist sat in a gallery at the Pasadena Art Museum facing his nude female opponent (the writer Eve Babitz) across a chessboard. This image, part of a series of now famous photographs, symbolizes several key features of the California creative situation, including the central theme of self-invention. Despite his friendship with the Arensbergs and Beatrice Wood, Marcel Duchamp is not particularly associated with California, nor should he necessarily be. Nonetheless, a recent book is devoted entirely to Duchamp in California, a nonsubject in the literature of modern art.[13] Among the guests at the 1963 opening of Duchamp's first retrospective was Andy Warhol, who had been given his first commercial show the previous year at Los Angeles's Ferus Gallery. We can draw several lessons from these art-historical "anomalies" that may clarify the circumstances in which art in California developed and was received.

The philosopher-critic Arthur Danto has noted that the position artists and works of art attain depends on their presence in, and contribution to, an ongoing critical discourse.[14] Regional art may be minimized or ignored altogether in this discourse, so that it is denied status and ultimately excluded from art history. Do such events as the Duchamp retrospective and the early Warhol exhibition demonstrate California's meaningful participation in American art and perhaps even in the transition from modernism to postmodernism? At the very least, the show in Pasadena may be seen as a challenge to New York hegemony. As such it represents a central problem in dealing with modernist culture in the regions: most of its recognizable manifestations were in fact imported.

But more important for our purposes is the positive creative situation embodied in the (self-created) image of Duchamp. Whatever his actual influence on Californians from John Cage and Clay Spohn to Bruce Nauman or Edward Ruscha, Duchamp provides a metaphoric presence in the California alternative modernist narrative, one that was well established before the 1963 retrospective. Above all, he represents the option of withdrawal from the art world, together with a sense of irony and distance and an eagerness to subvert certain high art assumptions, and thus embodies attitudes characteristic of Californians. The artist, excluded from full participation in a broader discourse, turns inward, seeking both validation and meaning in the relationship between self and the work of art.

In her own way the sculptor Claire Falkenstein fits this model. Despite her international experience in Paris during the 1950s as a member of Art Autre, the group that gathered around the critic and theorist Michel Tapié, she developed and maintained a modernist expression that depended very little on the work of her contemporaries. Her innovative use of materials, unconventional aesthetic decisions, and imaginative formal arrangements were already evident in her work of the early 1940s, when she was still in

Figure 9

Claire Falkenstein, Fertility ,

1940. Painted ash wood,

38 × 12 × 17 in. Collection

of the artist. Photograph

by Lou Meluso.

San Francisco (Fig. 9). And she continued in the same independent vein after her return to California some two decades later, ultimately developing a sculptural method and an aesthetic that were entirely her own. When asked recently who her artistic influences were, she responded that her own earliest works were her "mentors."[15]

The essays in this volume reinforce the idea that California artists worked in a peculiar situation that practically guaranteed an art of individuality and self-determination. California modernist art was different from that of the East Coast and contributed to a creative culture both removed from main developments elsewhere and linked to them. In such circumstances, as Cándida Smith argues, this art anticipated the end of modernism through a creative synthesis that transcended it. This idea of an unstable even artificial, relationship to Eurocentric culture is echoed by some of the other authors.

Bram Dijkstra's is the most insistent voice raised in support of California's artistic independence. He understands modernism as embracing the "regionalist" work of Phil Dike and even Millard Sheets, two artists representative of the group usually cast in opposition to the modernists. In so doing, Dijkstra focuses on other qualities that manifest a "modernist spirit" identified with the "linear expressionism"—as in the paintings of Charles Reiffel or Ejnar Hansen—adumbrated in Rex Slinkard's "sensuous perception of the material world." Above all, Dijkstra credits his regional modernists with both sophistication and an independence so genuine that for them California's isolation was congenial. To reinforce his point, Dijkstra focuses on less well known Southern California painters, avoiding leading figures such as Feitelson and Macdonald-Wright who more easily fit the established art-historical modernist profile.

William Moritz also looks at several "idiosyncratic" creators working at the margins of Hollywood film, California's only internationally recognized contribution to modern culture. He discusses visual music and experimental cinema as significant elements of the California avant-garde that provide a bridge between the worlds of high art and popular entertainment. Oskar Fischinger and Frederick Schwankovsky, in particular, emerge as emblems of the imaginative latitude and inventive opportunity afforded by an unstructured creative environment. Moritz even proposes that the influence of kinetic abstraction, in his view a mainly California phenomenon, extended to New York and affected, among others, Schwankovsky's former student Jackson Pollock. Moritz joins the other authors in identifying qualities that distinguish creative activity in California.

Even the chapters addressing international connections suggest that the local response is qualified by independence, reflecting the distinctive character and different needs of the regional society. Selz and Nieto are instructive on international presence and influence. Selz introduces us to representatives of old-world culture and modern art, including Lyonel Feininger, Fernand Léger, Max Beckmann, and Lászlö Moholy-Nagy. Furthermore, he recounts the contributions of émigré teachers such as Alfred Neumeyer, who made Mills College in Oakland a vital center for modernist ideas. But Selz finally acknowledges that the impact was less direct than might be expected given the cast of characters, suggesting that the region was evolving its own response to modernism. Conversely, as Nieto demonstrates, the influence from south of the border was considerable. In part because of its shared history with Mexico, California never developed a fully European modernist vision. Nieto's investigations of cross-cultural connections indicate a significant West Coast, particularly Southern California, role in more broadly understood modernist developments.

Susan Anderson brings a similar view to her assessment of the limited influence of French surrealism. Automatism, for example, was practically inimical to the artistic beliefs and practices of Lorser Feitelson. In fact, the postsurrealists and other California modernists reinvented surrealism to suit what they perceived as national cultural needs and goals. As Anderson points out, modern art is transformed in the hands and minds

of progressive artists working in a regional society to create for it an appropriate but distinctive culture. This basic theme appears and reappears throughout the essays in this volume.

In the same spirit of fresh inquiry, Susan Landauer examines the impact of World War II on American artists and their work. She considers several prominent California modernists and their individual responses to the war in a way that clearly sets them apart from their contemporaries in the East. In the process, she brings well-deserved attention to the works of, most notably, Clay Spohn and Hans Burkhardt. Burkhardt's war paintings are, in fact, a revelation that should call into question the prevailing view of postwar American art. Landauer insists that West Coast gestural painting is neither identical with, nor posterior to, that of the New York School. Extending her analysis beyond style, scale, and the "heroic myth," she looks at the possible effects of the war on individuals, drawing an important distinction between the westerners who served in the war and the mostly nonparticipant New Yorkers. Refusing to view California art merely as a regional reflection of modernist art elsewhere, Landauer joins the other authors in staking claim to a disparate, independent avant-garde and an art history reflecting the different experiences of life in the West.

Current historical revisionism and critical theory challenge many modernist assumptions about progress and hierarchy in art. As a result, ideas about the mainstream (primary, central) and the regional (secondary, peripheral) unavoidably come up for reconsideration. This anthology states some of the issues involved and encourages an approach to the art of California as more than a reflection or imitation of developments elsewhere. If David Harvey is correct in noting that the "complex historical geography of modernism [is] a tale yet to be fully written and explained,"[16] this volume represents a step on that particular path of inquiry.

In a postmodernist era when most critics and historians recognize the complexity of creative activity and diversity of expressive conditions that have both defined and enriched the broader American experience, it is no longer possible to support art-historical hegemony and all it implies for regional culture. We are suspicious of oversimplified, singular "readings" of cultural phenomena—or of history, for that matter. Under these circumstances, a repositioning of the elements of American art history is not only appropriate but imperative. For those of us involved in the creation of this book, California seems particularly well suited to the formulation of a truly national cultural narrative, one that embraces the edges as well as the center of American creative life.