Early Modernism in Southern California:

Provincialism or Eccentricity?

Bram Dijkstra

An encounter between Lorser Feitelson and Edward Hopper in the mid-fifties pointedly illuminates the price an artist must pay for not living in New York City. "Jesus," said Hopper, startled at seeing Feitelson, "I thought you had died somewhere way out in California a long time ago!" "I did," replied Feitelson, "but I wanted to be buried in New York, so they shipped me back here."[1]

To the East Coast art establishment the West remains, even today, a frontier of oddness and incoherence, a world of holy rollers and sand castle artisans whose works, like dreadful revenants, appear from time to time in New York galleries to help convince the world of the inherent sanity of Manhattan, Inc.

The juju of place has ruled the American art world throughout the twentieth century. An uncritical admiration for everything Parisian made critics genuflect until 1950, and since then an equally odd critical conviction that merely being in New York confers talent, grace, and sophistication upon an artist has guided most of our arbiters of taste.

Moreover, by 1920 the stylish had come to regard the urge to paint nature as an impulse of endearing, almost folksy, eccentricity. After all, the European leaders of modernism had roundly proclaimed the primacy of art over nature. The California impressionists, who were, in fact, doing their best work around this time, seemed therefore to many East Coast observers to be largely out of touch with current reality. But if the cliff dwellers of New York had come to regard a concern with the beauty and the dangers of the natural world as quaint and out-of-date, West Coast artists, whether they lived in isolated deserts, or in the coastal hills, or even in the ever more densely populated canyons of Los Angeles and San Diego, still had to cope with nature on a daily basis.

In 1920 conventional forms of landscape "composition," the human intellect's traditional method of taming the wilderness, unquestionably still reigned supreme in Southern California. According to Arthur Millier, the area's leading art critic of the

twenties and thirties, seventy percent of these landscapes were bought by tourists as souvenirs.[2] But although the art market in California continued to be dominated by an imagery that celebrated the particularities of the western landscape in a largely orthodox fashion, the artists who supplied this market were not necessarily more provincial than their colleagues on the East Coast. Most, indeed, had come from the East Coast and the Midwest and were, by 1920, at the top of their profession. Often they had left behind them substantial reputations in their move to California.

The term "provincialism" suggests a narrow, formulaic approach to artistic expression—a dislike for those who diverge from the norm. Artists who choose to go their own way on the basis of a conscious choice among options are not provincial but eccentric. Critics, usually a rather conformist lot, are often unable to recognize the merits of work that diverges from the prevailing cultural norms. By insisting on a narrow interpretation of whatever happens to be the reigning conception of normalcy in art, such critics often prove to be the true provincials.

I stress this rather obvious point because the word "provincial" crops up constantly in discussions of the art produced in Southern California prior to 1950. The members of the eastern art establishment were by no means the only culprits in this pattern of dismissal. The younger California artists of the twenties and thirties complained just as bitterly about the "provincialism" of their older colleagues and about the lack of taste of the Southern California public in general. The generation of 1950 did the same.

In reality, however, the range of styles pursued by the artists of Southern California from at least 1915, the time of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, to the present was no more provincial than anywhere else in the United States. Still, there was a significant difference in attitude between the painters who settled in Southern California in the period before the Second World War and those who might be seen as representative of the East Coast establishment. What distinguished them from the typical New York artists of this period was their fierce desire for personal independence and their disdain for the competitive infighting that had already become characteristic of the East Coast art environment.

It was as true during the twenties as it is today that artists who yearned for national fame must make their careers—or at least exhibit regularly—in New York. However, if you were a loner, if you saw the wide-open spaces of the West as the raw materials of the imagination rather than as a depressing range of empty bleachers in the vast stadium of potential fame—you might move to Southern California and settle in some (then still) outlandish place such as San Diego, Cathedral City, or Santa Monica. In such regions of true cultural isolation, a host of nonconformist artists settled during the first few decades of this century, determined to do their own thing—all the while, of course, muttering self-servingly about the miserable provincialism of the general public.

Lorser Feitelson, for instance, had this to say about the Southern California environment of the late twenties and early thirties:

For the few artists that were serious, when they came out here, they had no audience, no patronage, and if they liked it out here, they'd better paint for their own satisfaction! So they did their best work, because there was no competition. They didn't walk along Fifty-seventh Street or the equivalent, or rue Boetie in Paris or rue de Seine, to "see what is going on," or look in the art columns to see what is fashionable now, or who's getting the works, who's being lauded. It just didn't exist. You really had to love art. Therefore, you did the things for your own satisfaction, you worked on the same damn thing year in and year out until you got something to your satisfaction. And it ended there. This was the situation here. Therefore, we never had an art community like up in San Francisco.[3]

Hans Burkhardt, too, was well aware that, then as now, "you had to live in New York to get into the clique." Even though he knew that "you could be the greatest artist out here" and still be forgotten, he chose to settle in Los Angeles in 1937, finding in the relative isolation of his new environment an answer to the domestic and artistic confrontations of his New York years.[4]

For Edward Biberman the contradictory combination of personal isolation, wide-open spaces, and the developing cosmopolitanism of Los Angeles was an enticement rather than a detraction. "New York in the Thirties," he remarked, "was obviously a much more active area for the art experience than California." But Biberman was not looking for support groups: "By the time I decided to move to California, the very absence of what I had begun to feel as a kind of incestuous quality pervading the art scene in New York—the very absence of that in California became a plus factor." Biberman, in other words, was determined to escape the seemingly paradoxical pressure toward conformity always present among those who desire to be part of the "cutting edge" in art: "I was, very frankly, not interested in whether or not there were California painters whose work I admired. I was really much more interested in my feeling that this was for me a time of stocktaking, a period of gestation and the presence or absence of a large body of spectacular talents really didn't enter into my thinking.".[5]

Stanton Macdonald-Wright was driven by similar motives to settle in Southern California. In 1934 Arthur Millier was able to report that this early champion of synchromist abstraction had resettled in Santa Monica because "neither Europe nor the East Coast pleased him anymore. He hates New York.".[6] Macdonald-Wright, who moved restlessly between the poles of abstraction and realism, and who was as fascinated by traditional Asian forms of visual expression as by the Parisian avant-garde he had been a part of in the 1910s, had arrived in Los Angeles in 1919 thoroughly disgruntled by the New York establishment's unwillingness to be converted to the gospel of synchromism. Tired of "chasing art up the back alleys of New York," he "departed for the nut state," his good friend Thomas Hart Benton remarked in his 1937 memoir, An Artist in America , voicing the cultural establishment's prevailing opinion of California..[7]

Among the host of artists who settled in Southern California during the twenties and thirties, there were quite a few who did so because they found isolation congenial. These were artists who looked to their art, not to the art world, for support. Independent souls, they were clearly "eccentric." Born, bred, and trained in Europe, on the East Coast, or in the art schools of the Midwest, and usually keenly aware of what was being done by the most experimental painters of their time, they could hardly be accused of provincialism.

According to these loners there was even a significant difference between Southern California and San Francisco. Some were taken aback by the Bay Area's tendency to replicate a cultural scene they had deliberately chosen to escape. Lorser Feitelson, for instance, insisted that he had decided to live in Los Angeles rather than in the Bay Area because the close-knit art community in San Francisco reminded him of New York. He liked the fact that if you wanted to visit other artists in Southern California, "you had to take two or three days—one live[d] over here, another one very far in the opposite direction. Very few knew each other, or if they did, they never saw each other."[8] Though Feitelson overstated the diffusion of the actual art community of the region, his remarks indicate that many Southern California artists had clearly made a conscious choice to isolate themselves from their peers. Those who wanted to be part of a regional art community tended to gravitate toward the Bay Area.

The opposite was true for the determined "eccentrics." Even a San Francisco-born artist such as Helen Forbes early showed signs of restlessness within the framework of Bay Area art. Like most ambitious younger American modernist artists she had made a pilgrimage to Paris, where she had studied with André Lhôte. But unlike most she did not settle down easily in her native city afterward. Instead she often went in search of wild nature—painting in the Sierras, in Nevada, or in the mountains of Mexico. During the thirties, as a Works Progress Administration (WPA) artist, she returned time and again to Death Valley, painting its sensuous, anthropomorphic formations in a manner all her own (though stylistically related to the earth forms of Georgia O'Keeffe, as well as those of the Canadian Lawren Harris). Part of the time she would work, holed up alone in a ramshackle deserted inn, far from the art community of San Francisco, and part of the time she would spend in the Bay Area, an active member of the art community there and a co-founder of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists.

Dorr Bothwell, born in San Francisco in 1902 and brought to San Diego when she was nine, returned to the Bay Area to study art and subsequently followed a complex international trajectory quite similar to that of Helen Forbes, finally settling in Joshua Tree—but escaping to Mendocino for the summer. During the late thirties she painted remarkable, often haunting, enigmatic dreamscapes, and her abstract works on paper caught the attention of East Coast critics in the mid-forties.

Agnes Pelton was another of these notable eccentric itinerants. She was born in Germany of American parents, was trained in Europe, and exhibited at the Armory Show in 1913. She came to the Southland after another complex international travel

pattern. Arriving in California in 1931, she settled in Cathedral City, where the desert became the raw material for many of her eerie, surrealist, organic abstractions.

To settle in Southern California as an artist, then, you had to be, as Feitelson emphasized, quite sure you could live with your own art. It took self-confidence, independence, and an adventurous spirit to move here during the twenties and thirties, and the work of artists gifted with such characteristics was not likely to be dull and provincial. Our critics' preoccupation with New York-centric, and very narrowly defined, conceptions of American modernist art has left many of us with the mistaken impression that California's artists did not enter significantly into the realm of modernist experimentation until after the Second World War. But the artists themselves, by refusing to relinquish their independence of spirit, clearly also helped undermine their chances for wider recognition. A disinclination to self-promotion is as unprofitable in art as in business.

The year 1920 is an arbitrary but convenient dividing point between periods in American art. If the New York Armory Show of 1913 was a major influence on younger painters, so, for Californians, was the Panama-Pacific International Exposition of 1915. Though the art exhibited in San Francisco was considerably more conservative than that of the Armory Show, the fauvist pointillism of the Italian divisionists and the bravura brushwork of an international host of postimpressionist painters gave young California artists plenty to think about. But it took time for that influence to be digested.

By 1920 a new orientation toward visual expression, shaped by modernist concerns—though today not necessarily recognized as "modern art"—had become the norm among younger American painters. Influenced by the principles of abstraction, but rarely focusing on abstraction for its own sake, these painters continued to emphasize the expressive potentialities of content. The artists of Southern California appear to have been particularly receptive to this hybrid of styles.

In 1920 the modernist branch of the art world in New York was, in fact, all abuzz with discussions of the paintings of Rex Slinkard, a young Californian, son of a rancher in Newhall, who had died of influenza in New York City in 1918 at the age of thirty-one, while awaiting troop transport to Europe. Knoedler's was showing his work, and Marsden Hartley had already written a stirring memorial to the passing of this "ranchman, poet-painter, and man of the living world."

Slinkard, who had trained with Robert Henri, developed a lyrical, semiabstract form of symbolist painting in which he blended suggestions of music and dance into figural compositions. In Slinkard's paintings volume and outline alternately separated and blended to accentuate Wagnerian episodes of libidinal yearning. The highly original visual qualities of these works were effectively captured in Hartley's erotically charged description of Slinkard's method, written to accompany the Los Angeles Museum's 1919 memorial exhibition:

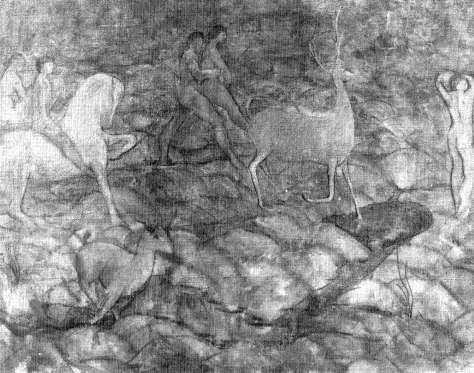

Figure 59

Rex Slinkard, Young Rivers (Riders) , ca. 1916. Oil on canvas, 38 × 51½ in.

Stanford University Museum of Art, Estate of Florence Williams.

He felt everything joined together, shape to shape, by the harmonic insistence in life and in nature. A flower held a face, and a face held a flowery substance for him. Bodies were young trees in bloom, and trees were lines of human loveliness. The body of the man, the body of the woman, beautiful male and female bodies, the ideal forms of everyone and everything he encountered, he understood and made his own. They were all living radiances against the dropped curtain of the world. He loved the light on flesh, and the shadows on strong arms, legs, and breasts. He avoided theory, either philosophic or esthetic. He had traveled through the ages of culture in his imagination, and was convinced that nothing was new and nothing was old [Fig. 59].[9]

Slinkard's sensuous perception of the material world sets the stage for an understanding of the visual preoccupations of most of Southern California's independent

modernists. The first exhibition of the Group of Independent Artists of Los Angeles, held in February 1923, included, as a tribute to Slinkard's influence, a number of his works, as well as paintings by Stanton Macdonald-Wright, Nick Brigante, Charles Austin, Boris Deutsch, Peter Krasnow, Edouard Vysekal, and Morgan Russell, all of whom shared Slinkard's concern with the intermodulation of color, form, and content. Each made the visual field of the painting into a celebration of all the senses. Each resolved the technical problems involved in such a project in markedly different fashion, and with variable success, but the attempt, already noted by Marsden Hartley in Slinkard's work, to make the body and the landscape coextensive, and to make each into a sensuous reflection of the other, is common to all these painters.

This pursuit of the tactile-visual correspondences between the human body and its material environment is expressive of a predilection for topographical anthropomorphism quite common among the painters of California—a fascination that need not surprise us, given the state's natural beauty. But the postwar modernist critics, with their insistence on "pure art," on an art that was to be "nonobjective" and uncontaminated by recognizable forms, tended to denigrate such "materialistic" concerns.

The self-declared post-Armory Show modernists were by no means the only immigrants to California tinkering with the boundaries of the traditional modes of representation. The state's primal natural environment drew many whose work defied all forms of categorization. Foremost among these was Charles Reiffel, who settled in San Diego during the mid-twenties. Emphatically a loner and an original, he fits the characteristics of the early-twentieth-century Southern California art refugee perfectly. Only someone compelled by his art and unimpressed with public acclaim would abandon a major East Coast reputation at the age of sixty-four to live in the dry, and during the mid-twenties still thinly populated, canyons of San Diego.

In the ten or fifteen years before his arrival there, Reiffel had gained his East Coast reputation as a tempestuous and idiosyncratic, fiercely independent postimpressionist landscape painter, whose work had become a familiar presence at the Corcoran biennials, the National Academy exhibitions, and the yearly American painting shows of the Art Institute of Chicago. Conservative critics hated his work, but the more adventurous ones championed him and compared him favorably to such much younger figures as Ernest Lawson, George Bellows, or even Vaclav Vytlacil, a young Turk thirty years his junior, who was to become a major presence in the Abstract American Artists organization of the thirties. In the March 1922 issue of Vanity Fair , Peyton Boswell had appended an appreciation of Reiffel's "happy combination of talent," on exhibition at the Valentine Gallery, to his glowing review of an exhibition of recent Italian landscapes by André Derain at the Brummer Galleries in New York.[10]

Reiffel's work of this period inspired lively debate among exhibition goers, and he was cast as the American van Gogh—whose work was indeed one of Reiffel's major inspirations. Traces of it can still be found in such major works of his San Diego period as his Morning, Nogales, Arizona of 1928. This work typifies Reiffel's method. In it, the

landscape comes alive with elemental power. Vermicelli-like strands of paint rush and splash thinly but insistently over the canvas, creating uncanny suggestions of sentient tensions, not only in plants and trees, but even in the inanimate forms of buildings, mountains, rocks, and soil. No doubt, Edgar Allan Poe would have loved Reiffel's work.

True to the fate of the loner painter seeking the lure of nature and a personal vision in Southern California, Reiffel's status as a national figure in the world of art declined the moment he moved to San Diego, although he continued to paint many brilliant canvases there, making the southwestern landscape lope and surge with suggestions of elemental movement and an ominous, almost preternatural, tension. The wealthy middle-class citizens of San Diego who would have been the potential buyers of his work did not understand the meaning of these strange masses of paint turned into undulating waves of primal matter, and during the depression years Reiffel, notwithstanding the welter of official awards and prizes which had been—and continued to be—bestowed upon him, descended into a state of abject poverty.

In his late years, rescued from starvation only by the existence of the WPA's various art support programs, he painted numerous rolling "bodyscapes" of the hills around San Diego, and such moody masterpieces as Rainy Evening (1937; Fig. 60) in which dense rain and lingering clouds transform the usually-too-hot concrete, brick, and asphalt of a parched city into the shimmering membrane of a restless organism bent on overpowering whatever might be merely human. Such paintings were commentaries on Reiffel's own tempestuous yearning. They are documents of his stoic yet unquiet sense of his own isolation from the rest of civilization. His restricted palette, dominated by blues and greens and yellows, combined with his fascination for long, seemingly uncontrollably trailing tendrils of organic form, has often caused his work to be naively misread as itself uncontrolled or "unsophisticated," even though the artist intentionally used paint and texture in a fashion directly in anticipation of the postwar concerns of the abstract expressionists. He apparently experimented (much as Knud Merrild did in Los Angeles a few years later) with a form of "drip-trail" abstraction well before Jackson Pollock. These abstractions were included in the 1942 Reiffel memorial exhibition at the San Diego Fine Arts Gallery but have not resurfaced since.

The narrow redefinition of what was "modern," and what not, that took hold in this country after World War II has, until recently, precluded serious reexamination of Reiffel's work, as well as that of many other stylistically eccentric American painters of the period between the wars. The postwar modernist aesthetic thus succeeded in trivializing the achievements of many strikingly independent and experimental artists whose work happened to be conceptually and stylistically incorrect within the context of the new criteria.

The experimental mood of the artists of the early twentieth century had, in contrast (as can easily be verified by the very wide spectrum of styles exhibited at the Armory Show), expressed itself through a broad-based, and stylistically variegated, set of skirmishes against the technical conventions of academic realism and its insistence

Figure 60

Charles Reiffel, Rainy Evening , 1937. Oil on board, 36 × 48 in.

Charles and Estelle Milch collection, San Diego.

on "pedagogic content"—on the facile depiction of "philosophic" subject matter expressive of middle-class values. Among these early modernists, the exploration of raw emotion in its most essential forms, through the innovative use of paint, color, and content (through figural expressionism, in other words, instead of abstraction for its own sake), was as frequently considered an integral part of the revolt against tradition as the notion that art should exist merely "as art." However, the move away from traditional forms of representation very early brought with it also the beginnings of the exclusivist mentality that was to come to full prominence after the Second World War. The remarkable early flowering of the Stieglitz group in the American cultural consciousness, and its continuing (and almost certainly still exaggerated) position of absolute prominence in our histories of American modernism, is a dramatic case in point.

But loners traditionally have been more important in the flowering of American art than movements and cliques. The early American modernists are very much a part of that tradition. It is therefore by no means surprising that some of the best among them

recoiled from the incipient dogmatism of the New York art world of the years between the wars.

As Feitelson, Biberman, and others have emphasized eloquently, these motives brought an unusual number of self-defined loners to the as yet culturally undefined reaches of Southern California during the earlier decades of this century. Some painters whose work is not in tune with the prevailing fashions are lucky enough to be able to survive in the more competitive art centers. Their work may subsequently, as the fashion changes, catch the attention of critics or dealers who have the power and the will to bring them to national prominence. Other artists have learned to promote their own work vociferously to gain the interest of those who are able to lead them to fame. Some artists are able to tolerate the conditions of the art marketplace; others cannot. Whether they are able or unable to do so has in itself nothing to do with the inherent quality of their work—but clearly artists who stay in the art centers, or who have been lucky enough to find a Stieglitz or a Clement Greenberg to promote them, have a much better chance of ending up in the histories of American art than those who, like Reiffel, are driven by personal demons and an all-pervasive preoccupation with the demands of their art. In consequence women and men who choose to pursue their work in outlandish isolation (such as that represented by Southern California's prewar art environment), almost inevitably end up being ignored by art history. The critics, unable to categorize their work, extrapolate from that a lack of direction or sophistication, and reward them consequently with casual dismissal.

During the twenties and thirties there were several other painters in California who, like Reiffel, were loosely associated with impressionism but whose work actually blended divisionistic techniques, fauvist color, and a modernist concern for essential form. Among these perhaps the most influential was Clarence Hinkle, who, having been appointed in 1921 as one of the first instructors of painting of the just-opened Chouinard School of Art in Los Angeles, became a mentor to such major California regionalists as Millard Sheets, Phil Paradise, and Phil Dike.

Though Hinkle was uneven, his best paintings tended toward an integration of broad, rhythmic patterns of line and bright fields of color. Often, at least in the manipulation of paint, they proved to be a good deal more adventurous than those of his students. His Laguna Beach (1929) gains authority from a superbly integrated architecture of color and ground, and a contagious delight in the calligraphic potentialities of line.

Another painter whose links with the California impressionists are at best rather tenuous is Thomas Lorraine Hunt, who was born in Ontario, Canada. Hunt painted complex ideograms of mood, which turned what would have remained ordinary land scape scenes in the eyes of lesser talents into visual messages about the links between the natural environment and our states of mind. Hunt was able to turn the scratch dab, and dash of the brush into a language of elemental equivalences between nature and the emotions. In a painting such as Fog in the Harbor , the heavy, dark tones of

boats and their shadows become the matrix upon which bright strokes of paint flash abstract points of color to countermand the pall of stasis established by the weight of the fog. In his broadly painted Grape Arbor , horizontal bands of paint are cross-hatched with dark stakes and a spare grape-stalk vermicelli that overtakes the top quarter of the painting to undermine the potential artificiality of the horizontals with a chaos of organic dribbles, dashes, and gobs of paint. It is a remarkable example of Hunt's ability to turn essential form into a passionate dialectic between the values of color and ground. Works such as this, with their evident concern for the abstract interaction of color, movement, and mood, show Hunt to have been, like Reiffel, in search of painterly principles not unlike the visual language that was to be codified as abstract expressionism in the postwar years.

The 1920s were a period of consolidation and reconsideration in American art. The avant-garde's move, during the 1910s, into experiments with cubism and related forms, and the pure color abstraction of Stanton Macdonald-Wright's synchromism, had attracted the attention of most of the talented younger painters. These proceeded—not to imitate these styles to the letter—but rather to adapt them to their own purposes. Clearly the younger California painters were as knowledgeable about the varieties of early modernism as their East Coast counterparts. Elements of fauvism, postimpressionism, cubism, and futurism pervade their work. Sometimes their experiments were indeed clearly "cutting edge," as in the case of Ben Berlin's work of the early twenties, which forms an interesting analogue to the visual music of Kandinsky, and carried such dada-inspired titles as Vudu Futhmique and Owngz . The same is true of Boris Deutsch's ventures into the realm of organic abstraction in works such as Rock of Ages —shown, like Berlin's paintings, at the first exhibition of the Los Angeles Independents in 1923. Berlin's whimsical pencil-drawn Portrait of that year is an excellent example of these experiments (Fig. 61).

Newly rediscovered styles, about which the artists might first have read in such magazines as the International Studio, Arts , or Parnassus , also influenced the work of the American painters of the twenties and thirties. Thus, along with adaptations of the work of Cézanne, Gauguin, Picasso, and Braque, the younger Californians absorbed lessons from the work of Giotto, El Greco, and the Mannerists. The word "primitivism" lost its association with the notion of "technical inadequacy," imposed on it by the academic artists of the nineteenth century, and came to stand for expressive spontaneity. African and Asian art and the folk art of Western Europe and America were finally being taken seriously.

If we accept the term "modernism" as descriptive of an aesthetic of formal experimentation, and "postmodernism" as representative of the eclectic reinterpretation and synthesis of the results of such experimentation, in conjunction with the exploration of stylistic impulses taken from earlier styles of art, we can easily identify the period of the twenties as the first postmodernist era in American art.

The eclectic tonality of the art environment of the twenties was further enhanced

Figure 61

Ben Berlin, Portrait , 1923. Pencil with embossing,

7 11/16 × 5 in. Private collection. Photograph

courtesy Tobey C. Moss Gallery, Los Angeles.

by the activities of numerous immigrant artists. They brought with them the expressive traditions of Russia, Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, and Italy and added these to the welter of styles that characterized the American art of that decade. One of the most striking results of this eclectic mixture of styles is the linear expressionism of a group of New York and Chicago immigrant painters. It is a style that to a certain extent overlaps with the cooler, much less impassioned—and hence more purely "modern"—preci-sionism of Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth, and Georgia O'Keeffe. But where the latter group was primarily concerned with the shapes and outlines of the city or the forms of nature, the work of the linear expressionists also focuses on the psychological dimensions of the human figure. Their work resembles precisionism in its pursuit of hard-edged, stylized delineations of natural and architectural forms.

This linear expressionism is strikingly characterized by the early work of Peter Krasnow, which insistently explores the interplay between flattened volumes and line.

Krasnow was born in the Ukraine and immigrated to the United States when he was seventeen. In Los Angeles, in 1925, three years after his arrival there, he painted a strikingly expressive portrait of an elderly man. The "kinetic properties" of the semicubist, semi—three-dimensional work of Albert Gleizes, with its emphasis on "shifting and moving volumes," that had much impressed Lorser Feitelson and numerous other young American painters at the Armory Show, would seem to have impressed Krasnow as well. In this expressionist portrait, for instance, fiat planes of color are bounded by hard-edged patterns of line and molded into casual simulacra of three-dimensionality by perfunctory shading. But Krasnow's line seems unwilling to maintain its integrity as a marker of separation between visual entities: a mountain abruptly becomes a chair, which turns into a blanket in support of an old man's body. The folds of the man's clothing have become a gauze that reveals the tuberous musculature of his ebbing flesh. There is a harsh, disconcerting element of cynicism and doubt in the face of this man. It leaves us with the impression that his sense of the meaning of being may be as disequilibrious as his pose and his semisunken, off-center position in the image.

The lower right corner of the painting is virtually a separate still life, emblematic of unquiet resignation, echoing in this respect the mood of existential doubt that courses through the entire painting. Had Krasnow continued to paint in this vein he would undoubtedly have become a central figure in the history of prewar Southern California art. Unfortunately, Krasnow's restless eclecticism led him to try his hand at so many different styles and modes of visual expression that he ultimately failed to gain a truly significant voice in any, except when, in his later years, he developed a densely patterned, kaleidoscopic style of abstraction—works that are brilliantly executed and as intricate and intriguing as oriental rugs, but with primarily a decorative, rather than an expressionistic, emotionally focused, intensity.

The precisionist tendency dominant in the American visual aesthetic of the twenties had actually arrived quite early in Los Angeles in the work of Henrietta Shore, who was born in Toronto, Canada, and was trained in New York and London. From 1915 until 1920 she lived in Los Angeles, but even after she moved to New York, she returned to California every summer, and in this manner she maintained a very active presence in the local art world until at least 1928, when she settled in Carmel. An effective, though still relatively conventional Los Angeles cityscape of around 1918 shows the manner in which the local contact between nature and the city may have suggested the "precisionist" linearity of industrial architecture to her. It was, in any case, a linearity she rapidly proceeded to incorporate into her work. A nude she painted the following year already strikingly combines line and volume in a linear expressionist fashion. The subtle molding of the background in this painting brings to mind the tonalities and shading of O'Keeffe's landscapes of the same period and helps to establish the sharply delineated sensuous weight of the figure in the foreground. Helena Dunlap is thought to be the subject of Shore's resplendently erotic scrutiny in this painting.

Shore was a close friend of Dunlap, another Los Angeles painter who was considered

a modernist by her contemporaries. Dunlap, a few years Shore's senior, tended toward postimpressionism in her work. Like so many other Americans of this period, she had studied with André Lhôte in Paris. Together with Shore she was given a two-person show at the Los Angeles Museum in 1918.

During the early 1920s, Shore continued to explore the expressive properties of simplified form in works that emphasized sharply delineated contrasts of color and line. Her Waterfall of 1922 is a remarkable example of her adventurous experiments of this period, which by 1927 had yielded to an equally adventurous hard-edged organic surrealism in such paintings as California Data , in which she surveys the sensuous qualities of the state's floral wealth.

The twenties and thirties produced an array of superb women painters whose work was often at least as rich and imaginative as that of their male counterparts, although one is hardly likely to discover this from a casual reading of the histories of American early modernist art, which seem to hold to the proposition that Georgia O'Keeffe was the only woman worth consideration in the field of painting during the period before 1945. Among these largely forgotten women painters, Belle (Goldschlager) Baranceanu figures prominently. Born in Chicago a few months after her parents' arrival there from Rumania, Baranceanu trained at the Minneapolis Art Institute and the Art Institute of Chicago. She came to live in Los Angeles in 1927 and 1928 and, after returning to Chicago, finally settled in San Diego in 1933.

Baranceanu was strongly influenced by the linear expressionism of Anthony Angarola, a leading Chicago modernist of the twenties whose student she had been. However, she soon developed a personal style emphasizing the juxtaposition of fiat fields of color and strongly accentuated, essential line. Her work was considerably less busy, less three-dimensional, and more concerned with color values than his. Baranceanu had an uncanny ability to reduce the forms and structures of the material world to their sensory essence. In early works, such as her Leaf-Bud of 1925, she brought her work close to abstraction. Leaf-Bud combines the close-up sensibility of O'Keeffe's flower studies of the same period with a forceful interest in the abstract compositional properties of color, plane, and line.

But Baranceanu's love for the essential shapes of nature made her turn away from complete abstraction and toward the creation of carefully organized compositions, which in controlled sequences of line mapped the volumes, hues, and textures of sensuous experience. Equally adept at landscape, figure painting, and still life, Baranceanu brought her determinedly modernist yet very personal sense of style to bear upon The Yellow Robe , a portrait of her sister painted in Los Angeles in 1927 and shown that same year at the Los Angeles Museum's annual American Painters and Sculptors exhibition (see Plate 7). In this composition, the regal figure of the sitter gains strength and authority from carefully balanced horizontal and vertical rectangles of complementary color, which with only minor further simplification could have led the painter to a Mondrianesque exploration of pure geometric abstraction.

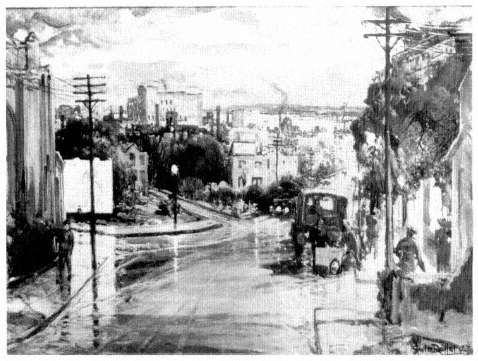

The following year Baranceanu exhibited a view of Los Angeles from the hilltop house in which she lived at the time, close to downtown. From Everett Street is remarkably European in sensibility, although Baranceanu never visited Europe. There is a striking stylistic affinity between this work and some of the angular, stylized, flattened cityscapes Egon Schiele had been painting during the 1910s. Since there is no indication and little likelihood that Baranceanu was familiar with these works when she painted From Everett Street , the similarity is most likely due to a correspondence between the visual sensibilities of the two painters rather than to direct influence.

From Everett Street is part of a splendid series of paintings and lithographs of Los Angeles created by the young painter during her sojourn there in 1927 and 1928. These works vary from Cézannesque explorations of the landscape as a series of receding planes to brilliantly colored industrial images such as her study of a brick factory in Elysian Park, whose subject matter parallels Charles Sheeler's explorations of the geometry of the American workplace. Other works in this series, such as Sunset Boulevard at Everett Street , bring an angular poetry to the streets of the city, and in Hollywood Hills Baranceanu pits the tensions of nature against the encroachment of city life by making patterns of color and form interact in a manner reminiscent of the organic semiabstractions of Arthur Dove.

During the thirties, strongly influenced by Diego Rivera, Baranceanu became San Diego's foremost mural painter, a figure of diminutive physical stature who boldly designed and executed gigantic visual narratives virtually single-handedly. This left her little time for easel painting, and thus her later work in this medium is relatively rare. Since her mural work was of necessity site specific, her art was rarely seen beyond San Diego, but in that city she was without doubt the most influential modernist presence until after World War II.

Baranceanu's paintings of 1927 and 1928, focusing on Los Angeles's Everett Street region, prefigure the expressive concerns to be found in the justly celebrated Angel's Flight of 1931, by Millard Sheets. This painting is one of the quintessential American urban images of the depression decade. But Sheets's flirtation with linear expression-ism was regrettably brief, apparently not predating 1931 and giving way to a more decorous—and more decorative—form of stylized regionalism as early as 1933.

In Angel's Flight the extraordinary interplay of fiat urban surfaces and an almost infinitely receding "abstract" pattern of perspectival planes helps to give the figures in the foreground a remarkably sensuous three-dimensionality. Unfortunately, examples of this expressionist-realist phase of Sheets's art are rare. Sheets was too "civilized," too much a tourist in the natural world, one is tempted to add, to be able to sustain the expressive intensity of Angel's Flight . In certain of his later paintings, as in the stately, somber rhythms of Abandoned (1934), he was still able to recapture the remarkable balance between form and content he had achieved in Angel's Flight , but he soon aligned himself with the artificial, patronizing populism of regionalist painters such as Thomas Hart Benton and moved inexorably toward the often cloyingly decorative qualities of his work after 1945.

Figure 62

Phil Dike, Copper , 1937. Oil on canvas, 30 × 40 in. Phoenix Art Museum.

The linear expressionist quality lingered a bit longer in the work of some of Sheets's closest compatriots and followers at Chouinard. Paul Sample, Barse Miller, Phil Paradise, and especially Phil Dike (see Fig. 62) all did a great deal of work during the thirties that seems to have found its initial inspiration in the stylistic qualities of Angel's Flight .

Among the numerous artists who earned their living by working in the motion picture industry, some developed distinctive personal styles that often remained geared to the visual requirements of the movies even while attempting to break through the medium's oppressive demands for "realistic" imagery. The work of Warren Newcombe is particularly remarkable in this respect. He had studied painting in Boston under Joseph De Camp, and started out painting portraits in a style not unlike that of his teacher. By 1920 he was in Hollywood. His work moved through a phase in which he painted fuzzy symbolic landscapes similar to those of Claude Buck toward a Matisse-

inspired sense of line. By 1931 he had developed a strikingly individual, self-consciously antiacademic manner of painting landscapes, using flat planes of color and broad, heavy outlines to turn scenes seen from what would otherwise be a rather ordinary perspective, into wonderfully sinuous, semiabstracted dreamscapes. In these works echoes of the styles of Rockwell Kent, Marsden Hartley, Charles Reiffel, and even Vincent van Gogh bounce off against Newcombe's amusing sense of the organic world as the backdrop for a cosmic movie. Edward Weston described Newcombe's art perhaps most effectively: "He has emotion as well as intellect; he feels deeply the American scene. Into his canvases go exhilarating vitality, joy of life, intense drama. Essential forms rise starkly stripped, or swirl with energy. Color vibrates, is alive."[11]

Another figure who came to prominence in California during the depression years was Ejnar Hansen, who, after having lived in the Midwest since 1914, moved to Pasadena in 1925, where he painted startling character studies of tormented or eccentric men and world-weary young women on the edge of disintegration. These paintings, which capture much of the neurotic tension of modern life, are among the finest examples of twentieth-century portraiture. Hansen's extraordinary series of paintings documenting the physical decline of the important art critic Sadakichi Hartmann presents a chilling record of an intellect forced into gradual capitulation to the agonies of a decaying body.

Like many other early-twentieth-century American painters who had found their inspiration in modernism, Hansen almost completely abandoned the flattened, linear elements of expressionism in his work of the later thirties. Instead he began to explore a broadly painted yet quite accessible and "populist" imagery, very characteristic of the realist tendency in thirties art. This latter tendency was represented in California by a wide variety of poetic realists, including Emil Kosa, Jr., Edouard Vysekal, Sueo Serisawa, Everett Gee Jackson, and Dan Dickey.

Within the present context it is clearly impossible to give all the California artists who contributed to the adventurous modernist atmosphere of the interwar years the attention they deserve. I have deliberately moved away from discussing the work of major figures such as Feitelson, Macdonald-Wright, and others who have been invoked time and again by writers steeped in postwar critical values as proof that faint traces of "good" modernism could actually be discerned in Southern California even before 1950. The still relatively obscure artists I have chosen to feature here represent a selection that, though by no means arbitrary, could easily have been restructured to feature several other groups quite as deserving of our attention. A focus on Feitelson and his entourage might have been the subject of another approach. The Arensbergs, their Los Angeles circle, and the importance of their collection to the progressive artists of the region would have represented a more traditional focus.

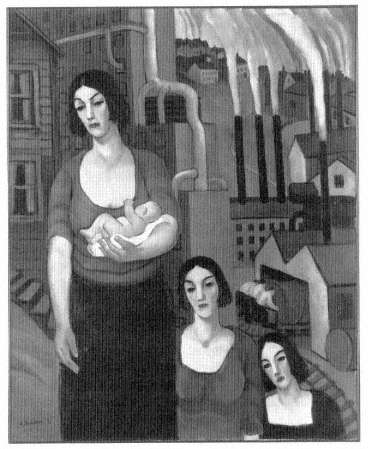

In truth, the early modernist art of the area represents an embarrassment of riches. The work of Arthur Durston, who was a major formative influence on Morris Broderson, is always intriguing. His paintings of women stoically contemplating land-

Figure 63

Arthur Durston, Industry , 1934. Oil on canvas, 50 × 40 in. National

Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, transfer from

U.S. Department of Labor.

scapes ravaged by devastating floods and his Industry of 1934 (Fig. 63) give to average people the static, monumental dignity of the principals in a Sophoclean tragedy. Durstoh's paintings are exemplary of the manner in which some of the painters of the thirties were able to conjoin social commentary with modernist formal considerations.

Knud Merrild in his flux paintings of the forties, such as Flux Bouquet and Sidereal Parturition (Fig. 64), played on the viewer's tendency to turn abstract matter into "representation." The controlled accidents of paint-in-flux that formed the basis for his compositions take on a semblance of the essential forms of nature's flora and fauna in a reversal of the process Reiffel had used to turn his elemental earthscapes into near abstractions by exploiting the visual correspondences between our sense of what constitutes landscape and the organic suggestions always inherent in loosely controlled strands of paint.

Helen Lundeberg, in such paintings as Plant and Animal Analogies (see Plate 8), her dreamscapes of the mid-thirties through the forties, and her painting Microcosm and

Figure 64

Knud Merrild, Sidereal Parturition , 1947. Oil flux on Masonite,

20¾ × 15¼ in. Photograph courtesy Tobey C. Moss Gallery, Los Angeles.

Macrocosm (see Fig. 13), produced some of the best images of myth and mystery art can hope to offer us, while the perfection of her Self-Portrait of 1933 is enough to startle any viewer with its ability to turn reality into a realm of magic.

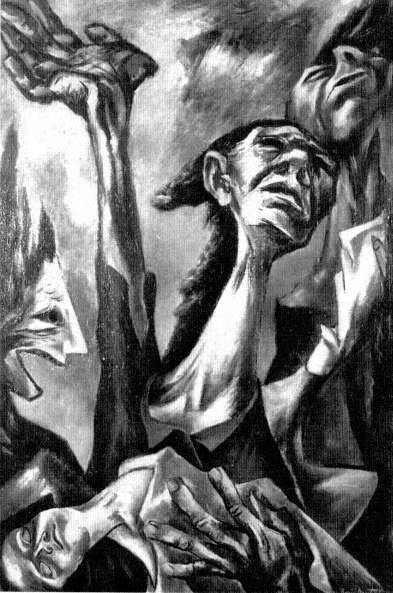

Philip Goldstein had, well before he became Philip Guston, become expert at combining surreal and expressionist imagery. His documentation of fascist violence and its attendant human suffering in the extraordinary Bombardment of 1937-38 is a superb example of the visual complexity the California painters were capable of bringing to their work. In a similar fashion, Hans Burkhardt was able to portray the nightmarish dimensions of war in a manner that shocks, yet adds to, the viewer's humanity. Surreal, yet all too real, his paintings of the forties are among the world's most chilling evocations of the brutal carnage of the Second World War: the bloody screams of anger of a gentle soul (see Plate 5; Figs. 15, 16).

Much the same can be said of Boris Deutsch, who was able to capture the panic, anguish, and exasperation many felt when it became clear that the war had ended only to plunge the world into a new "cold war" of emotional terrorism. This is "What Atomic War Will Do to You," Deutsch told his viewers (Fig. 65).

Paintings such as these emphatically demonstrate the inaccuracy of the frequent assumption that before 1950 all West Coast art was "soft" and mired in sunlight fantasies of easy living. In fact, even painters such as Edward Biberman, who dealt with the everyday particularities of the social environment of Southern California, were often able to evoke complex emotional responses by combining realistic imagery with a modernist sensibility. Biberman was a visual poet, his work a West Coast analogue to that of Edward Hopper. At his best he turned Southern California's perpetual impulse toward an all-inclusive eclecticism—an abiding lust after visual stimuli—in upon itself.

Biberman, the Philadelphia-born son of Russian immigrants turned American industrialists, surely was the quintessential postmodernist, painting effectively in a style he had invented long before the conceptual framework for that style had even been conceived. He was able to evoke the various moods of Los Angeles in a sequence of paintings that expressed his anger at the region's casual wastefulness of human hopes and talents as well as his admiration for its recklessly inventive appropriation of architectural forms. In his paintings of the immediate postwar years Biberman captured the essence of urban Los Angeles perfectly. Here the squares of Josef Albers meet the empty city streets of Hopper and the hard-edged precisionism of Sheeler at, of all places, the Hollywood Palladium (see Plate 9). In paintings such as these Biberman effectively anticipated the productions of far better known postwar chroniclers of the "new" California, such as Edward Ruscha and David Hockney.

Our current myth about art in California posits a sudden flowering of artistic genius after 1945. But we would do well to remind ourselves that artists such as Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Philip Guston, and Jackson Pollock did not merely pass through California; they received part of their early impetus and art education here. Not all the perceived stars of American art were touched by genius only after they arrived in New York—in

Figure 65

Boris Deutsch, What Atomic War Will Do to You , 1946.

Oil on canvas, 66½ × 46½ in. Judah L. Magnes Museum,

Berkeley, gift of the artist's estate. Photograph by Ben Ailes.

most cases, one suspects, the "discovery" of their genius was predicated upon their dutiful pilgrimage to the city. The many loners hostile to the trappings of self-promotion among Southern California's artists of the pre-1945 era inevitably created a framework particularly conducive to their subsequent obscurity within the context of our national art-historical memory of the twenties and thirties.

Critics, like artists, tend to gain authority among the public the more they are obsessed by absolutist rules about art. Yet anyone who has ever heard two equally good artists with different convictions about the nature and function of art savage each other's work should know that the more absolute a critic's convictions are, the less they should be trusted. The postwar era fostered a narrowly defined dualist sensibility that spoke to the "us-against-them" cultural mentality of the cold war. It could be argued that there has never been a more simplistic and provincial period in American art criticism than the fifties.

The absolutist single-mindedness of the critics of the late forties and early fifties exerted such a powerful hold over the American art scene that many worthy dissident early modernists were banished from our public memory almost overnight. Their rediscovery has been slow and erratic, determined largely by the prevailing fashions in art. Fortunately things are now beginning to take a new turn. Eclecticism is in. The tide of fashion has turned toward an ever-broadening pluralism. This stylistic eclecticism or, as we fondly (but inaccurately) designate it, postmodernism, is now encouraging us to look with renewed interest to the artistic productions of the twenties and thirties, that first great age of postmodernism.

A wide-ranging freedom to choose among styles and expressive options is the key to any creative art environment The diversity of qualities to be found among the works of the lone tangers of Southern California's art scene of the prewar years is testimony to these artists' true independence of spirit, and to their sophistication—for they knew very well what they were building upon and what they were fighting against. What separates their postmodernism from ours, however, is their sense of history, their conscious desire to forge a synthesis between the modern and what had come before. Without historical knowledge, artists are doomed to a parochialism that forces them to slam-dance blindly in a closed circle of options, and to remain stuck, as so many are today, in a world of disconnected sound bites, tape loops, and sampled music, a world of imitation and re-creation and parody—helpless waifs of an "avant-garde" that has nowhere to go because it has no idea where it came from.