Letterboxing, Mon Amour

The problem of scale has, from the first, been linked to the related issue of aspect ratio. CinemaScope and other wide-screen processes were developed (along with high-fidelity stereo sound) with the purpose of overwhelming viewers with an experience not available on their televisions at home. On the other hand, sale of broadcast and video rights of theatrical features represents a lucrative source of revenue, necessitating a means of squeezing wide-screen images into the TV frame. But you cannot fill the TV frame without either cutting off edges of the film picture, or through anamorphic compression, turning the films into animated El Grecos.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in maintaining the theatrical aspect ratio for video viewing. Unfortunately, this interest has bred the fallacious notion that there is a single "correct" aspect ratio. In fact, it is the rule , not the exception, that there is no single "correct" aspect ratio for any wide-screen film. For example, during photography, it is common for directors and cinematographers to "hard matte" some, but not all, of their shots if they expect to exhibit in 1.85 or 1.66. If you examine the negative, some shots would be matted for 1.66, say, and others at full frame 1.33. Which is "correct"?

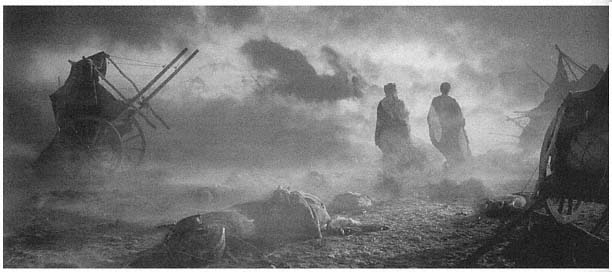

Full reproduction of Lawrence frame, without matte

Frequently, too, the ratio of photography will be altered when a film changes gauges. A film might be shot in nonanamorphic 70mm at 2:1, reduced to anamorphic 35mm at 2.35:1, then reduced to 16mm at 1.85:1. (The Lawrence of Arabia disc, for example, was produced from a 35mm source, meaning a slight loss of vertical information.) Then there are those processes, like VistaVision, that were designed to be shown at different ratios. As if that weren't complex enough, most projectionists show everything at 2:1. Is "correct" based on intention, gauge, exhibition, breadth of distribution, amount of visual information, . . .?

While it might be more prudent to think of an "optimal" aspect ratio, rather than a "correct" one, who should choose the optimum? Asking the director or cinematographer perpetuates the auteurist mystique while assuming that the filmmaker knows best how a film at home should be watched. This approach further assumes that these people are best equipped to translate film images into video images. To privilege film technicians, then, subordinates video to film.

Prior to the involvement of the film's technicians, optimality was visually determined by concentrating on significant dramatic action and sacrificing composition and background detail (by cropping the edges of the frame). When composition made such reframing impossible (when, for example, two conversing characters occupied opposite edges of the frame), then a "pan-and-scan" optical movement was made; or the frame was edited optically into two shots.

"Full frame" TV image with pan-and-scan

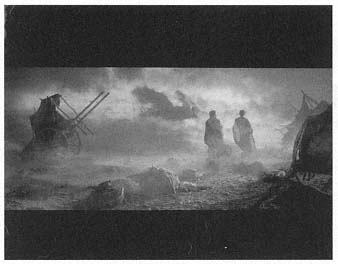

"Full frame" TV image with letterboxed full film frame

Pan-and-scan transfers are performed largely to preserve narrative and to approximate the theatrical experience by keeping the entire television frame filled. There is an implicit assumption that the vertical dimensions of the film frame must be maintained. Letterboxing maintains the full horizontal dimension of the wide-screen image. In effect, pan-and-scan transfers privilege the television (thus subordinating film to video). It is more important to fill the TV frame than it is to maintain cinematic composition. Letterboxing reverses that priority by preserving the cinematic framing.

But a transformation occurs in maintaining composition. (If it didn't, letterboxing wouldn't be controversial.) In his essay "CinemaScope: Before and After," Charles Barr writes:

But it is not only the horizontal line which is emphasized in CinemaScope. . . . The more open the frame, the greater the impression of depth: the image is more vivid, and involves us more directly.[12]

If Barr is correct, letterboxing, by merely maintaining the horizontal measurement of the 'Scope frame, cannot duplicate the wide-screen experience. Letterboxing equates the shape of the CinemaScope screen with its effect .

In fact, while letterboxing subordinates the TV screen to cinematic composition, it simultaneously reverses that hierarchy. If film is usually considered larger and grander than TV, wide-screen film letterboxed in a 1.33 TV frame subjects film to television aesthetics by forcing the film image to become smaller than the TV image. Thus, in the act of privileging film over video, video ends up dominant. (The movement from 70mm theatrical exhibition to 19-inch home viewing is one long diminuendo of cinematic effect.)

Moreover, letterboxing is an ambiguous process, with all the resistance ambiguity encounters. A letterboxed image is neither film nor TV. Its diminished size makes it an impossible replacement for the theatrical experience; at the same time, the portentous black bands at the top and bottom of the screen remind the video viewer not only of the "inferiority" of the video image to the film original (it can only accommodate the latter by shrinking it) but also of a lack. What is behind those black bars? Edward Branigan makes the point that the frame is "the boundary which actualizes what is framed" and that "representation is premised upon, and is condemned to struggle against, a fundamental absence."[13]

The absent in film is everything outside the visual field. In a letterboxed transfer of 'Scope films, the matte hides the bottoms and tops of the outgoing and incoming frames. Viewing the film without the matte would make it impossible for us not to be aware of the "cinematicness" of the image, since we

would be viewing frame lines in addition to the picture. The mattes for "flat" wide-screen films (1.85:1 and 1.66:1) frequently blot out production equipment such as microphones, camera tracks, and so on, that the director or cinematographer assumed would be matted out in projection.

Both frame lines and extraneous equipment are part of the repressed production process. To see them ruptures the classical diegesis. And the fact that such a violence to our normal cinematic experience is necessary in video would call attention once again to the differences between the media. A double exposure of ideology would occur: of the repressed aspects of cinematic projection (frame lines, equipment)[14] and of the presumed neutrality of the transfer procedure.

Yet there is no useful alternative to letterboxing.[15] Form and composition are important; useful analysis of films on video cannot be performed when 43 percent of the image has been cropped, and certainly no one can claim to have seen(!) the film on video under such circumstances. If maintaining the horizontal length of the image creates the fiction that the cinematic experience has been approximated, it is nonetheless a fiction worthy of support. Besides, letterboxing introduces aesthetic effects of its own.

The frame created by the matte contributes one more effect toward treating the cinematic image as an object of analysis. Just as the frame of a painting directs our gaze toward the painting enclosed, so too the letterbox calls attention to the aesthetic qualities of the image framed. But that may be the problem; if people object to letterboxing, it's because it turns their classical narratives into formalist galleries. (Consider how the ponderously pseudo-epic qualities of Lawrence of Arabia get lost in a background blur on video, refocusing attention on the flatness of the image and compositional precision.) In fact, letterboxing does precisely the opposite of what Barr likes about wide-screen:[16] it ends up accentuating composition, rather than effacing it.