Chapter 8

Ministerial Intervention and an Unexpected Outcome

Once the Mémoires des plantes appeared, Dodart's control over the natural history of plants grew stronger for a time. His view that the project should be published in installments was adopted, and he chose the plants to be distilled. Throughout the 1680s he directed the project, although he could never get it published. In the 1690s Homberg and Tournefort supplanted Dodart, just as he had replaced Duclos. These new members reinvigorated research and molded it to their own interests while Dodart's responsibilities as médecin ordinaire to the king eroded his participation in the Academy; indeed by 1699 he even needed a special dispensation to receive his pension because he missed so many of the Academy's meetings. When Homberg and Tournefort entered the Academy at the end of 1691, the one investigated Bourdelin's research at the behest of the ministerial protector, while the other saw how to use Bourdelin's research himself and preempted Dodart's plans. But they were not the first to thwart Dodart, whose project was imperiled by the Dutch Wars, by highwaymen, and by an illness of the king.

The Lost Second Installment

Dodart wanted to publish essays on plants annually, or at least in regular installments. He thought that the second volume of his natural history of plants should set out generalizations and exceptions and describe individual plants.[1] Hoping that the public would share his interest in explaining

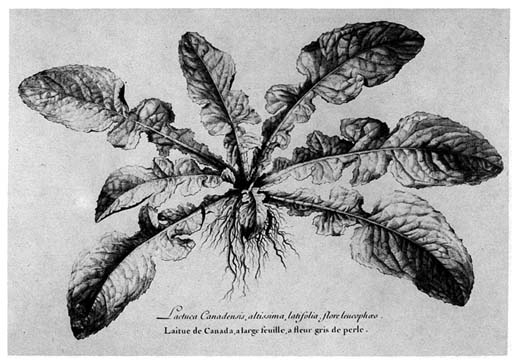

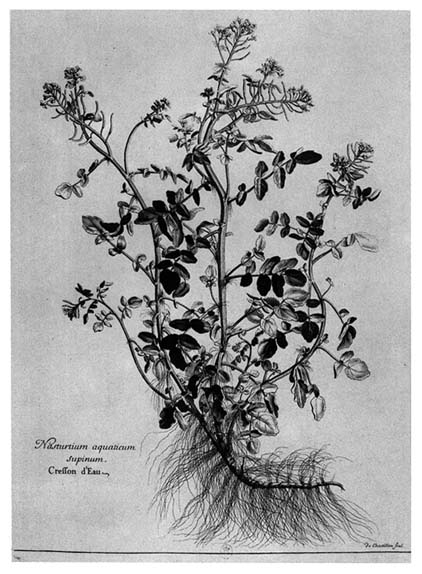

nutrition, he planned to write not about the rare plants that intrigued Nicolas Marchant but about homely vegetables that formed part of the diet, such as "coriander, lettuce, wild and domesticated chicory, watercress, etc." (figs. 10, 11).[2] This concern with nutrition greatly expanded the work. From 1676 to April 1678, Bourdelin analyzed more than four hundred and fifty plants and animals for Dodart. In the spring of 1679, Jean Marchant sowed more than four hundred different seeds from France and abroad, "with the object of describing them for the general history of plants."[3]

Between August 1680 and mid-June 1681, Dodart wrote the second part of the natural history of plants and prepared three other treatises for publication. But he fell victim to a dreadful scholarly accident. All of his treatises — the second part of the natural history of plants and the works on medicine, natural philosophy, and plants — were stolen from him. Du Hamel had to explain the loss to Colbert:

…all these treatises which ought to have composed a good volume were stolen from him on his way into Paris, where he was bringing them in order to complete them for the printer; and since all the efforts which he has made to recover them have been futile, he has been obliged to redo the two most important of these treatises, and to collect from his papers anything that he can find that will help him rewrite the other works.[4]

The highwaymen were probably so disappointed with their worthless booty that they threw it away, but Dodart had to spend the rest of the year rewriting the stolen treatises.[5] By mid-December 1681 Du Hamel could report that among the books ready for publication were Dodart's "Deuxième partie du projet de l'histoire des plantes" and "Analyses des plantes," and Marchant's "Environ 200 descriptions de plantes gravées."[6] The first two were apparently reconstructions of the stolen books. By December 1681, therefore, despite the theft of Dodart's manuscripts, the Academy was ready to publish three volumes pertaining to the natural history.

Why were these works never published? It cannot have been disputes about distillation that delayed publication, for by separating the "Deuxième partie" and the "Analyses des plantes," Dodart had insulated the uncontroversial aspects of the Academy's work from contamination by chemical analyses of uncertain merit. Blame for the failure to publish lies partly with the academicians and partly with their patron. Many of Marchant's descriptions were inconsistent with the plates or with earlier treatises, and discrepancies had to be resolved before publication. Financial reasons also delayed publication. Funding for the Academy diminished in the late 1670s, and in the 1680s Colbert still refused to release funds for

Fig. 10.

Lactuca canadensis, altissima, latifolia, flore leucophaeo/Laitue de Canada, à large feuille, à fleur

gris de perle. (From Estampes ; artist unknown; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

Fig. 11.

Nasturtium aquaticum supinum/Cresson d'eau. (From Estampes ; engraved

by Chastillon; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

engravings despite persistent appeals from academicians. When the king visited the Academy at the Bibliothèque du roi in December 1681, academicians presented him a list of treatises ready for publication, to no avail. But these refusals must have been couched in encouraging terms, for academicians continued their work, and morale in the early 1680s was better than it had been a decade earlier. They lived on promises and persevered.[7]

Even the transition from Colbert's to Louvois's ministry did not at first disrupt work on the natural history of plants. During the first thirty months of Louvois's protectorship, work continued apace, especially on engravings, which Louvois had reinstigated. Louvois encouraged academicians to ready their work for print. His ministry marked closer ties between the Academy and the Jardin royal, especially with Fagon and Tournefort, whom Fagon took under his wing. Fagon chose plants for Chastillon to draw for the Academy's "Mémoire des plantes," and Louvois sponsored Tournefort's herborizations in the Iberian peninsula.[8] In the winter of 1684 the Company planned to work on roots, seeds, and woody parts of the plants that had been engraved, while Bourdelin continued his analyses.[9] In 1685 and 1686 Dodart and Marchant concentrated on engravings and descriptions.[10] In 1685 Du Hamel believed that the Academy would soon publish a volume of the natural history of plants, for which many engravings were completed.[11] But after 1686, the grand botanical compendium was mentioned in the minutes only as a project of the past.

Ministerial Intervention

What explains this abrupt abandonment of the natural history of plants? Academicians had overcome editorial rivalry, discouragement about chemical analyses of uncertain merit, theft of manuscripts, and parsimony prompted by the Dutch Wars. Despite all of these discouragements, they researched and wrote for publication. But in the mid-1680s a new and more dangerous impediment arose. What jealousy, controversy, theft, or economy had not accomplished, ministerial interference did. The Academy's botanical work was injured by misguided enthusiasm on the part of its patron.

When a patron's own interests interfere with the conception or execution of a creative project, the quality of work suffers. Interference from a patron who does not understand the technical language and skills or the theoretical assumptions of the work can be especially damaging.[12] This is precisely what happened. In 1686 Louvois intervened, upsetting the delicate

balance between theoretical and practical expectations. Academicians had hoped that their natural history of plants would benefit medicine and add to basic knowledge about the nature of the world. They disputed among themselves as to whether sound theory was a basis for or an outcome of practical advance. But no academician advocated choosing between utilitarian and abstract goals; rather they debated the precise relationship between practical and theoretical knowledge. Into this scholarly discussion was injected a ministerial command to obtain practical benefits at the expense of theoretical research.

Louvois took an interest in natural history and preferred it to the other sciences partly because he thought it promised the quickest utilitarian results. He became especially impatient when the king's life was endangered by a serious illness that his physicians had been unable to treat effectively.[13] Looking for a scapegoat, resenting an Academy that could not save its monarch's life, needing more funds for Louis's wars, and expecting scientific inquiry to lead inexorably and swiftly to improvements in the quality of life, Louvois lost patience. He told the Academy how to do its work.

At the meeting of 30 January 1686, Henri Bessé de La Chapelle, Louvois's spokesman in the Academy, read a short paper to academicians. Willfully insulting and openly disdainful of the Academy's chemical research, La Chapelle warned academicians that they must move in new directions. He exhorted academicians to eschew "curious" research, which he called "a game" or "an amusement of the Chemists," and to apply themselves instead to "useful research that has some connection with the Service of the King and of the State.[14] La Chapelle recommended that academicians study medicine, improve and republish Duclos's book on mineral waters, try to desalinate sea water, and analyze wines. He also discussed the relationship among medicine, natural philosophy, and the natural history of plants:

The other research more appropriate for this Company and which would be more to the taste of Monseigneur de Louvois is anything that can illustrate natural philosophy and serve medicine, these two things being practically inseparable, since medicine takes consequences and profit from the new discoveries of natural philosophy.[15]

La Chapelle believed that the Academy's chemical analyses were worthless because they belonged not to the practical realm of botany and medicine but to the abstract and theoretical realm of natural philosophy. The Academy's natural philosophers controlled chemistry and the natural history of

plants, and they stood accused of subverting these subjects by seeking the underlying causes of things.

While La Chapelle agreed that practical results followed from theoretical discoveries, he noted that chemical research at the Academy seemed to make little progress in either direction. For that reason he warned the Academy to concentrate on empirical matters. In singling out Duclos's book on French mineral waters for praise, La Chapelle cited a work that perfectly blended science, medicine, and chauvinism to please a royal patron interested in practical accomplishments. Furthermore, Louvois and La Chapelle unerringly criticized the most vulnerable of the Academy's projects, the one that had stirred personal and theoretical controversy and whose publications were few by comparison with its cost. Whatever Louvois's motivation — Louis's nearly fatal illness, some behind-the-scenes influence, or impatience with a project much discussed but showing few practical results — his instructions were clear. Academicians were to spend more time on medical research. He would continue to support the natural history of plants only so long as the Academy adjusted its contents to his expectations.

Since Louvois never repudiated his spokesman or his instructions, he must have been content with La Chapelle's speech.[16] Other academicians perhaps agreed, for only eighteen months later La Hire explained La Chapelle's role to Huygens, to whom he sometimes complained about Louvois's policies. Louvois, he said, had "entirely committed the care of our academy" to La Chapelle, who "does us the courtesy of attending our meetings and of communicating to us his good ideas (belles lumières ) in the sciences."[17] La Chapelle's place in the Academy was assured and his harangue of January 1686 was heeded by academicians, up to a point.

La Chapelle's speech is a curious blend of criticism and advice, of general statements about method and specific suggestions for research, of familiarity with and ignorance about the Academy's chemical research. Many of his suggestions were superfluous. Duclos, Dodart, and Bourdelin had already studied the tastes of plant distillants, analyzed earths, and tried to desalinate sea water.[18] Academicians had always sought medical applications of their work and planned to include the medical uses of plants in the natural history. La Chapelle named specific vegetable and mineral substances — mercury, antimony, quinine, laudanum, poppy, tea, coffee, and cocoa — for study,[19] but academicians had already examined them. Perhaps, in his awkward double role as ministerial spokesman and as colleague of the academicians, La Chapelle was trying to soften Louvois's criticisms implicitly by proposing work he knew his colleagues had already

performed. Louvois's motives are clearer than La Chapelle's, but the effect of the speech, no matter what its genesis, was unmistakable.

La Chapelle's talk had marked repercussions. First, academicians no longer presented papers about the natural history of plants. Second, the chemists were more carefully supervised and had to draft new research proposals. Both Borelly and Dodart immediately suggested projects incorporating Louvois's requirements, and Du Hamel turned over the chemical proposals to La Chapelle in April 1686.[20] During January 1688 Borelly was asked to keep a notebook of his chemical experiments, and he presented his findings to the Wednesday assemblies.[21] Third, chemical analyses emphasized the potentially useful natural products of plants, such as gums and materia medica. Fourth, medical remedies became an even more common topic of discussion at meetings. Fifth, fewer plants were described or engravings verified than in previous years.[22] Sixth, only two other papers on plants were read; one was a letter sent to academicians about a deformed pear, and the other was Sédileau's report on the insects that caused galls in the bark of trees in the royal orangerie.[23] Thus the only botanical paper produced by an academician from 1686 until 1690 concerned a disease of Louis's orange trees, not disinterested inquiry but institutional flattery of the patron. The years 1688 and 1689 represent the nadir of botanical research in the seventeenth-century Academy. Only Bourdelin continued his normal research, perhaps because while working at home he could isolate himself from ministerial pressures. When La Hire reported the Academy's activities to Huygens in 1690, he did not mention any work on plants.[24] By the time Pontchartrain took over the Academy from Louvois, botanical research at the Academy had very nearly collapsed.

With the decline in pure botanical research, academicians emphasized the nutritional, medical, and industrial uses of plants and their products. In 1688, 1689, and 1690, they assessed a coffee-flavored beverage brewed from roasted rye, tasted the milky juice in common chicory, considered a remedy for hemorrhoids, and compared methods of treating wood to obtain good charcoal.[25] Only in 1690, when Louvois's health and interest in the Academy were declining, did La Hire revive the study of plant vegetation and Dodart and Marchant again read descriptions of plants.[26] Their example was lauded by Gallois and, oddly, by La Chapelle, both of whom urged a study of roots.[27] Despite this flurry of activity, Louvois's reprimands about curious research and chemical games had both an immediate and a lasting detrimental effect on the natural history of plants; the project temporarily came to a halt and never recovered its full vigor.[28]

The natural history suffered from fiscal exigency and internal difficulties

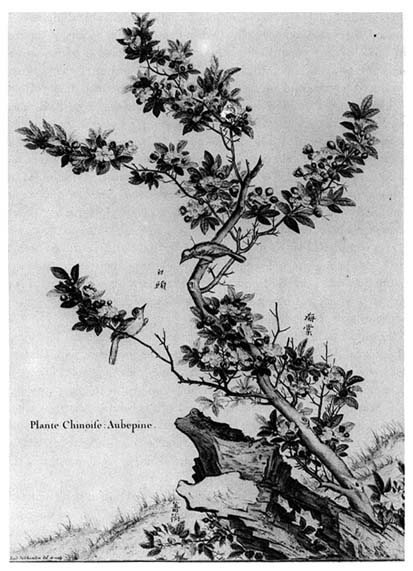

both intellectual and personal, but ministerial manipulation was decisive.[29] Indeed, theoretical botany revived when Pontchartrain became protector. In 1692 Dodart planned botanical research and read a paper on the structure of the bud of a tree, while La Hire demonstrated that fig trees produced flowers, and Tournefort and Marchant described plants for the Academy's new monthly publication.[30] Observations sent from the Far East fired enthusiasm and broadened the scope of inquiry, so that the Academy inspected drawings of hitherto unknown Chinese plants (fig. 12) and studied the root of ginseng.[31] Dodart reported the growth of leaves and shoots on an elm felled fifteen months earlier. Tournefort examined an unusual mushroom, the flowers of Apocynum maius syriacum rectum cornuti, and the contraction of fibers in certain plants.[32] Morin de Toulon discussed a plant called tartunaire in Provençal, and La Hire fils described how a vine attaches itself to walls.[33] La Hire and Sédileau studied orange trees, and Jean Marchant reported on his and his father's emendations of Bauhin's Pinax .[34] In 1697 Dodart pointed out that the base of a tree's crown was always parallel to the ground in which the tree grew.[35] No longer did botanical presentations emphasize utility.[36]

Finally, Tournefort and Homberg agreed that the natural history of plants should be published, and they cooperated for a time with Dodart, Marchant, and Bourdelin. By 1692 Dodart and Marchant were once again reading descriptions of plants to assemblies almost as frequently as they had before 1686.[37] They also compared plants with engravings, while Bourdelin analyzed plants and Homberg and Tournefort studied his findings.[38] Homberg was initially enthusiastic and his manuscripts confirm that the Academy expected to publish the natural history of plants during the 1690s.[39]

In the number and variety of botanical activities and in the balance of pure and applied research, the 1690s were a period of marked improvement. Ministerial appointments spurred this revival. Unlike Louvois, who named relatively unknown scientists to poorly paid positions and added no chemists or botanists to the Academy, Pontchartrain selected well-known and respected scientists — Boulduc, Homberg, Charas, and Tournefort — and paid some of them decently. At least as important, he and Bignon allowed academicians to control their research, insofar as the royal treasury could underwrite it. Finally, in appointing Tournefort, Pontchartrain injected into the Academy a savant with a forceful intellect and powerful backing who would usurp the natural history of plants and shape it to his own purposes.

Fig. 12.

Aubépine (plante chinoise). (From Estampes; drawn and engraved by

Chastillon; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

A New Editor

Pontchartrain's choice of Tournefort had obvious merits. Tournefort shared many interests with Jean Marchant, Dodart, and Bourdelin, and he collaborated with other colleagues on varied research.[40] He agreed that it was important to correct errors in traditional botanical literature and to develop the medical uses of plants.[41] Like the Marchants, Tournefort advocated collecting information from all countries on the medicinal uses of plants; he believed that the task merited royal patronage and promised new cures for dangerous diseases.[42] His descriptions of plants reinforced the efforts of Dodart and Jean Marchant.[43] He studied Bourdelin's chemical analyses of plants and examined the chemical constituents of soils. He also conjectured about the constituents of mixed bodies and the medicinal properties of plants. These ideas had been the hope and despair of Duclos, Dodart, and Mariotte before him. Along with his colleagues, Tournefort tempered expectation with doubt, for he was skeptical of ascertaining the "the primary qualities" or the "configuration of the parts" of plants and soils.[44]

Even Tournefort's Élémens de botanique complemented the Academy's other botanical research. It was an intellectual prolegomenon to the Academy's natural history, although its cost delayed publication of the latter.[45] Tournefort classified plants and rationalized their nomenclature, did not include in his engravings "pictures of the entire plant," and omitted the "virtues" of plants from his descriptions.[46] Thus the Élémens laid the groundwork for the Academy's natural history of plants, which Pontchartrain's and Bignon's policies seemed to revive.

Tournefort promised in the introduction to his Élémens that the compendium would soon appear:

The Royal Academy of Sciences, which has made Botany one of its principal activities, will soon furnish to the public some papers about the natural history of plants, with illustrations, descriptions, and analyses, all worthy, if one may dare to say it, of the magnificence of the King, and which will demonstrate just how far the science has been perfected.[47]

Yet the work he predicted so confidently in 1694 was not to appear. Within four years Tournefort himself sabotaged it. His next major book, the Histoire des plantes qui naissent aux environs de Paris of 1698, superseded the Academy's natural history of plants. Thus the unexpected outcome of three decades of research was the usurpation by a new member of prerogatives clearly staked out by his colleagues.

After 1694 the Academy decided not to publish its grand natural history

of plants. Homberg retracted some of his optimistic assessments of Bourdelin's analyses, and Tournefort's Histoire des plantes announced that the Academy's natural history would never appear in the form originally conceived. Granting the importance of correcting previous botanists, Tournefort nevertheless deprecated any plan to begin "a general history of Plants on the basis of new expenses." This caution was sensible during the 1690s, but coming from the author of the costly Élémens, it must have struck some of his colleagues as unseemly and self-serving.[48]

Tournefort's Histoire des plantes supplanted and transformed the Academy's natural history. Unlike his Élémens, which solved a problem that academicians had disregarded, the Histoire des plantes drew on the botanical work of Dodart, Bourdelin, and the Marchants. Tournefort's book grew out of his lectures at the Jardin royal and also out of the Academy's work. It credited the Marchants with supplying plants for analysis, used Bourdelin's research to delineate the medical uses of plants, and included alternative plant names such as the Marchants and Dodart had painstakingly collected. Tournefort, however, did not make their intentions his own. Instead he focused on plants in the Paris region that were medically useful. In so doing, he made an unwieldy mass of data manageable, and he captured the sentiment of academicians that the medical implications of Bourdelin's work were its most viable dimension. He also revived Duclos's idea that the Academy emphasize French flora. Eighteenth-century academicians viewed his book as the sequel to Dodart's Mémoires des plantes , while Tournefort declared it to be the first of several regional natural histories of French flora.[49]

In effect Tournefort divided the Academy's project. In appropriating the description and analysis of useful local flora to himself, he left foreign flora to Marchant. Marchant worked until the end of his life on the old project, but after publishing 319 engravings in 1701 he got no further with its publications.[50] When Reneaume and Terrasson tried to revive the natural history of plants in 1709, their conception of the work was considerably different from his.[51]

Tournefort redefined the Academy's natural history of plants and welded a new alliance between the Academy of Sciences and the Royal Garden, with the latter dominating. His role in the Academy during the 1690s resembled Dodart's during the 167Os: both entered the Academy with influential mentors, assumed direction of a project that seemed to be floundering, and published specific parts of the Academy's research. Their books appeared under their own names and reflected the research of other academicians, although Dodart overstated and Tournefort minimized the

contributions of his colleagues. Tournefort isolated Marchant's work but published some of the Academy's results in forms that its original proponents could not have foreseen. When at last the engravings appeared as Les plantes du roi in the eighteenth century, they brought to an elegant close the series of publications that represented the seventeenth-century Academy's failed natural history of plants.

Conclusion

The Academy's corporate character affected its scientific inquiry, by providing continuity of goals across the lifetimes of individual members and by encouraging division of labor within research teams. These advantages favored ambitious projects. But the natural history of plants never came to fruition as planned because it was plagued by serious problems. The goals of research were unrealistic given the methods available. Chemical analysis was difficult to interpret. Relations among academicians were not harmonious. Funding was erratic, and manuscripts were stolen. Ministerial intervention on the side of practical rather than theoretical research damaged morale.

Neither the structural benefits of collaboration nor the relative independence of strong-minded individuals entirely surmounted these problems. Dodart and Tournefort faced a difficult choice. If they were true to the original intentions of the project, these would become a straitjacket. But if they changed its goals, reported research selectively, and published their own views rather than those of their co-workers, they alienated fellow academicians. Both chose the latter course.

By contrast the Academy's work in the natural philosophy of plants required little team effort yet achieved a modest success. It was carried out by academicians who worked independently of one another and did not always submit research plans to the institution or its protectors but instead read finished papers to their colleagues preparatory to publishing them. It enjoyed minimal material support from the institution but at least was free from ministerial interventions.[52] In the natural history, academicians emphasized experiment and observation over theory, but the uncertain theoretical implications of that work undermined the project. In the natural philosophy, theory and experiment were more effectively wedded. If the natural history of plants tested the Academy as a company that produced science, the natural philosophy of plants revealed it as a company that reviewed what its individual members had produced. For the natural history the institution provided labor, materials, experiment, observation,

and analysis; for the natural philosophy the institution served primarily as a referee of ideas. Academicians' failures in the natural history revealed tensions between the Academy and its patrons in the seventeenth century; academicians' achievements in the natural philosophy helped establish the pattern of the Academy's activities in the eighteenth century.