Chapter 6

The Natural History of Plants:

Rival Conceptions

The Academy was the realization of the House of Solomon, an instrument of royal propaganda, the hub of a sociopolitical network of influence. But it was more. It was a catalyst for thought whose facilities, customs, and corporate self-consciousness influenced the work its members performed. The institution cannot be understood apart from its scientific research and writings, for these were its ostensible raison d'être. Whatever other functions the Academy had, a satisfactory scientific performance was a necessary condition for its survival.

The Academy's interests are so broad as to elude detailed analysis in any one study. Concentrating on a single facet of its research, however, clarifies both the discipline and the institution. Botany offers a particularly rewarding case, for under the influence of chemistry, microscopy, anatomy, and physiology, it was changing. By academicians' own standards, moreover, much of their botanical research was a failure, and the historian can often learn more from failures than from successes. Since some of the Academy's work on plants attracted the concern of its protectors, it clarifies the direct and the indirect effects of patronage. Finally, with respect to organization of research and modes of reasoning, studies of plants resemble other projects at the Academy and thus offer a key to the institution as a whole.

Changing Ways of Thinking About Plants

Academicians thought of research on plants as being of two types: descriptive natural history (l'histoire ), which will be discussed in chapters 6

through 8, and explanatory natural philosophy (la physique ), which will be discussed in chapters 9 through 12.

The concept of natural history goes back at least to Aristotle, whose Historia animalium lays out what its author knows about animals, organizing that knowledge into such categories as number and type of limbs, mechanisms for eating, and mode of reproduction. Aristotle offers a series of generalizations, each modified by exceptions and strengthened by comparisons. Subsequent natural histories always contained these two elements: they enumerated the pertinent facts and they generalized in order to organize the facts. Aristotle's book introduced his treatises on the functions of the various parts of the body, reproduction and generation, and other aspects of a natural philosophy of animals. It was the necessary preliminary to causal analysis. But the blend of assumption and generalization in Aristotle's work, as in the natural histories of later authors, betrays a pattern of causal thought embedded in the method itself.

Surveying the two-thousand-year-old tradition of natural histories, Bacon tried to clarify their uses and limits. Perhaps in revulsion against the magical or superstitious element found in many of them, he declared that a good natural history should present fact shorn of explanation. A natural history of the world would enumerate all observable phenomena, category by category (for example, winds, heat and cold, plants, animals, and minerals). Only when savants had compiled this information could they ascertain the underlying causes of phenomena, that is, examine the natural philosophy of the world. Given the immensity of the first task, an ideal Baconian approach would make it difficult ever to reach the second stage.

Some natural histories, consistent with Bacon's recommendation, did little more than illustrate and describe flora and fauna without explaining their behavior or nature. Bauhin's Pinax, for example, the most comprehensive seventeenth-century guide to plants, described the external appearance, cultivation, and uses of each plant. Zoologists, tempted by analogies between human and animal behavior and impressed by the lessons of comparative anatomy, went further. In his ornithology, for example, Aldrovandi not only portrayed the skeletal structure and reproductive organs of birds but also discussed the development of the chick in the egg, the roles of male and female in reproduction, and the sexual mores of fowls. For Aldrovandi, knowing animals entailed knowing their anatomy and physiology and explaining their behavioral characteristics. Aldrovandi's and Bauhin's different methods show how the natural histories of plants and animals diverged at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Zoological research was prompted primarily by comparative anatomy,

while the principal incentive to study plants was pharmacological, so that books on plants tended to be practical manuals.

In the course of the century, however, several influences altered ideas about how to study plants. The conceptions of natural history and natural philosophy changed, bringing botanical and zoological research closer in intent and method. First, the number of known plants grew quickly, making new compendia necessary. Second, among the species discovered in the new world were sensitive plants (fig. 1), which challenged the old Aristotelian distinction between plants and animals, for they moved when touched. Third, aesthetic appreciation of plants and gardens as objects of beauty was developing, and with it a desire to collect botanical illustrations. Insofar as this change represented a taste for plants on their own merits — and not as symbols or simples — it also represented a new way of thinking about plants that would affect botanical studies. Fourth, by redefining the differences between humans and animals, mechanistic theories created a greater incentive to test assumptions about plants and animals — especially the view that plants and animals were analogous in many respects — by searching for the limits of their similarities. Fifth, savants tried to put their causal accounts of the universe on a new footing. Astronomers sought a new celestial mechanics and developed a mathematical key to the language of the universe, while students of terrestrial phenomena turned to chemical and mechanical explanation to account for animal and vegetable processes. Sixth, as new scientific fields emerged and the interdisciplinary character of scientific inquiry was placed on a firmer footing, traditional fields were redefined and theories or methods that developed in one area were applied to another.[1]

All of these factors influenced botanical research, which emerged in the late seventeenth century as a more independent field of study. From the appearance of Bauhin's work until the 1660s, no major treatises on plants had appeared. But during the 1660s Robert Hooke included plants in his Micrographia, Johann Daniel Major suggested that sap circulated in plants like blood in animals, and Robert Morison and John Ray began a new assault on the problem of classification. By the 1670s Nehemiah Grew was publishing anatomical studies of roots and stems, and Marcello Malpighi took up these inquiries in the 1680s.

The Academy was thus founded at a time when botanical research was in flux, exhibiting at once conservative and innovative elements. The Academy's own projects reflect both tendencies. Academicians settled quickly on publishing a definitive natural history of plants, to be produced as a team effort. This study was old-fashioned and stressed descriptions,

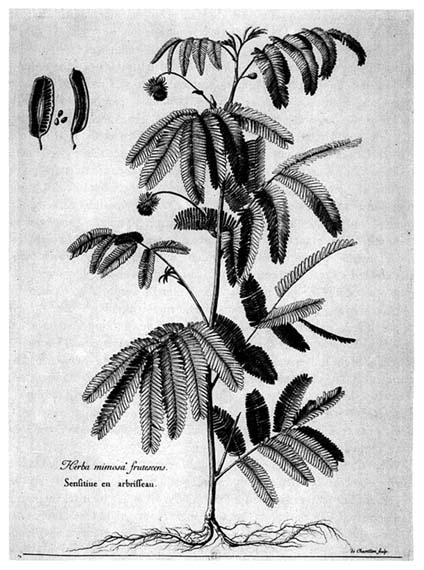

Fig. 1.

Herba mimosa frutescens/Sensitive en arbrisseau.

(From Estampes; drawn and engraved by Chastillon;

photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

lists of synonyms and sources, explanations of medical uses, tips on cultivation, and illustrations, all reminiscent of Bauhin. At the same time, however, academicians introduced new elements such as the chemical analysis of plants. The blend of old and new features, the research methods chosen, and the roles of the patrons and of the institution all contribute to the story of the Academy's natural history of plants. By and large, that story is one of failure. Academicians recorded hundreds of pages of botanical notes and compiled more than twenty volumes of notebooks from chemical experiments. They drafted assorted chapters, prepared more than three hundred engravings, and wrote several books. But they never published the natural history as planned.

The Academy's natural history of plants failed for four reasons: intellectual, natural, accidental, and institutional. The project was intellectually ambitious, its scope and style innovative but overly inclusive. Academicians never focused their inquiry adequately but studied plants rare and common, medicinal and edible, French and foreign. They disagreed about how to describe plants — where to start, what to emphasize, and how to balance bookishness and observation — and they were sometimes undecided whether a specimen corresponded with a plant already described in the literature. Natural obstacles, such as obtaining and cultivating uncommon plants, also taxed their ingenuity. Since they did not keep a herbarium of dried specimens, they could not always check their descriptions or illustrations. Such intellectual and natural problems were not peculiar, however, to academicians. Anyone writing a natural history of plants faced these difficulties, and academicians' solutions and mistakes resembled those of their contemporaries.

The Academy's project was distinctive in certain respects. It was to include chemical analyses of the plants. It was the work of an institution, not an individual. It suffered from editorial rivalry, uncertain funding, and theft. The patronage that made the project possible also undermined its completion. These special features of the project contributed to its failure. Academicians were able to isolate the most treacherous intellectual problem — chemical analysis — from the project, but they could not prevent the accidents and institutional problems that damaged their natural history. To understand how all these factors affected the project, it is necessary to know why the Academy decided to prepare a natural history of plants at all, how innovative the project was, what was the institutional character of members' efforts, and how patronage influenced their work.

Proposals for a Natural History of Plants

Between 1550 and 1700, the number of known plants quadrupled while the number of botanical compendia declined.[2] If only to take account of discoveries, a new natural history of plants seemed a necessity in the late seventeenth century. In 1674 John Ray pointed out the absence of a "general History of Plants." He complained that in order to have the available botanical lore in a single work, it would be necessary to combine the publications of Bauhin, Columna, Alpin, Cornut, Parkinson, Margrave, Morison, and Boccone.[3] Most of the authors he cited were no longer active. But when Ray wrote, members of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris had already committed themselves to just such an undertaking as he described. One of their earliest plans was to publish a general natural history of plants.

Huygens was the first to propose that the Academy publish a natural history. The project he described was Baconian and all-encompassing, intended to investigate weight, heat, cold, light, color, magnetic attraction, the composition of the elements, animal respiration, and growth in metals, plants, and stones.[4] The Academy would assign topics to its members, who would report weekly on their findings. This stilted proposal helped convince Colbert and his advisers to found the Academy, but Huygens's colleagues modified his ideas and adopted two specific projects for the anatomists, botanists, and chemists. These were the natural histories of animals and of plants.

It was Huygens's friend Perrault who suggested in January 1667 that the Academy publish a natural history of plants.[5] Perrault too was influenced by earlier models, especially Bauhin's Pinax, which Nicolas Marchant had already begun to revise. Perrault tried to define the field and to differentiate the kinds of research required for a comprehensive study of plants. He identified two ways of studying plants: "pur Botanique et Risotome" and natural philosophy. The former studied the "histoire" of plants by "botanizing" or "herborizing," that is by collecting plants and roots and studying their external characteristics and medical applications.[6] The latter Perrault defined, in the Theophrastean and Baconian tradition, as the inquiry into the causes of medical properties of plants or of vegetable reproduction and nutrition. For such research he envisaged chemical analysis, microscopic observation of seeds and shoots, tests of theories about propagation and generation, and studies of whether sap circulates like blood.

Perrault's plan of research for the natural history was more bookish than

experimental. It was at once grandiose and modest. The Academy would treat all known plants in a comprehensive publication containing descriptions, illustrations, and a topographical index, but would take its information from existing literature. Because classification was problematic, Perrault proposed that academicians choose an existing system or dispense with one entirely. A catalogue of all known names of plants would be useful, but ancient names and descriptions could not always be correlated with modern plants. The compendium would be illustrated from watercolors painted by Nicolas Robert for the duke of Orléans rather than from life.[7]

Like Huygens, Perrault had a traditional conception of natural history. He referred to the ancients but not to the Americas, and indeed the Academy looked primarily to Europe and the Near East for unusual species, leaving American flora to the Minim Charles Plumier. As a physician, Perrault also stressed the medical merits of the project, urging academicians to correct and expand materia medica. The Academy's task was to collect useful information as efficiently as possible and make it available to the public.[8] This literary approach especially suited a society that had existed formally for only one month, as yet possessed no laboratory and little apparatus, and still used meetings to plan or debate. Perrault was also uncertain about the extent of royal patronage. A modest proposal, firmly rooted in work already begun, stood a chance of succeeding and might stimulate a more broadly conceived project, if only Colbert would authorize it.

By criticizing Robert's paintings, Perrault ultimately justified expanding the Academy's project. He showed that aesthetic criteria did not meet scientific needs. Most of the paintings did not show roots or indicate the relative size of a plant, defects that would trouble a scientist but not a connoisseur. Perrault's remedy was to add the missing roots and to depict leaves, fruits, and seeds in blank corners of the page (fig. 2). Should the Academy be allowed to commission illustrations from life, however, Perrault recommended that the artist portray the plant life-sized or provide a scale and show the important parts of plants; when the appearance of a plant changed markedly as it grew, the artist should depict both the young and the mature plant.[9]

Perrault's colleagues were not content with studying books but wanted to study nature. They would start with the literature and go beyond it. Indeed, since European botanical literature referred to only a small proportion of known plants, the greatest need was to study the new or "rare" plants. Here, too, the Academy was influenced by work begun by Guy de La Brosse and the duke of Orléans, especially since Marchant had worked

Fig. 2.

Lychnis umbellifera montana helvecita/Lychnis à umbelles.

(From Estampes; drawn by Robert, engraved by Chastillon;

photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

for the latter at Blois. But the Academy also added an experimental twist to Perrault's natural history by incorporating chemical analyses designed to explain what they were describing. This was Duclos's contribution to the project.

As director of the project, Duclos quickly put his own stamp on it.[10] To the basic elements — engravings and descriptions of plants — he added a classification according to Theophrastus's system.[11] He also expanded the descriptions to compensate for the faults of the illustrations. Descriptions of the size, parts, and products of plants would form a catalogue of characteristics that would distinguish one plant from another. He stressed for example the "carriage" or appearance (le port ) of the plant in the earth, that is, whether a plant was tall (eslevée ), or rested its branches on the earth without sending out roots from them (couchée ), or rested its branches on the earth and sent out roots from them (rampante ), or leaned (appuyée ). Duclos also demanded precise descriptions of the root, trunk, leaves, flowers, fruits, seeds, and natural products such as gums, resins, or liquids.

In a more radical departure, Duclos added chemical analysis to the work. He planned to distill plants in order to mention in the descriptions the consistency, color, smell, and taste of distillants. He hoped to discover the chemical constitution of plants by analyzing their distillants, by testing a decoction of sap or juice in various solutions, and by studying crystals formed by condensed juices.[12] Because Duclos believed that chemical explanation of organic matter was fundamental, he made chemical analysis an integral part of the natural history of plants. Under the guise of description, therefore, he introduced inquiries that bordered on natural philosophy. In so doing Duclos set the natural history on a new and difficult footing that made the project controversial and delayed its completion.

Duclos also thought the natural history should have a regional bias, focusing on French flora. Thus, he recommended that the common French names be in the list of synonyms of plants:

And because we plan to write this natural history in the French language, it would be good to be informed about the names which the common people in the major French provinces give to each plant, so as to add them to the names used in other languages.[13]

The natural histories of plants and animals, like nearly everything academicians wrote, were published in French. The Academy intended to reach above all a French audience. First and foremost, that meant the king, the ministerial protectors, and the persons to whom they distributed the book, as a group probably unfamiliar with Latin. Duclos's interest in popular

French names for plants was controversial, however, and his proposal allied him with the "moderns" against the "ancients" and with the "realists" against the "purists." The same controversy raged in the Académie française, which ruled out of its dictionary neologisms and technical language, the very vocabulary that Antoine Furetière struggled to learn for his own dictionary. Within the Academy of Sciences Duclos had many allies, for academicians coined words so that they could write about plants in their own language, and in the 1670s French names were added to some of the plates.[14]

Duclos's request that the Academy study only French plants was less palatable, despite its advantages. Valuing experience over authority, Duclos wanted descriptions to reflect direct observation, which was possible only when the plants were near at hand. He believed that the provincial flora of France were insufficiently appreciated in scholarly circles. He wanted the Academy's project to be manageable, and he worried that plant species varied when transplanted. Academicians, however, resisted this restriction. In the late seventeenth century gardeners were proud of the exotic flowers and fruits they could cultivate, and Louis XIV's nurseries and orangerie were famous for defying climate and seasons. Connoisseurs and savants alike wanted to expand their knowledge of flora and fauna, not limit it to what was native to France. Although Duclos's proposal was formally approved, the Academy never stopped cultivating, describing, and illustrating rare plants and never limited its projected book along geographical lines.[15] The resulting lack of focus impeded the project.

The Academy accumulated proposals and smoothed over disagreements. Its corporate procedures and plans grew by accretion and ignored inconsistencies. The successive adoption of Perrault's and Duclos's proposals exhibits this tendency well: in some areas they agreed, in others they disagreed, and the Academy simply glossed over any problems of coherence between them. Where Perrault and Duclos were in harmony, they reflected a centuries-old approach to studying plants, with Perrault emphasizing illustrations, Duclos text, to convey information. Duclos also improved on Perrault, whose language had sometimes been vague. But Duclos wanted the natural history to concentrate on French flora and to include chemical analysis, which Perrault regarded as more appropriate to the natural philosophical studies of plants. In any case, when the Academy formally approved Duclos's recommendations in 1668, a basic framework for the natural history existed. The designers were Huygens, Perrault, and Duclos, but the research and writing were almost entirely the responsibility of Nicolas Marchant and Bourdelin.

Duclos quickly lost control of the project to Dodart, who entered the Academy in 1671. His statement of principles appeared in the Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire des plantes , published in 1676 with Marchant's Descriptions de quelques plantes nouvelles . The books were an inconsistent introduction to the project, for Dodart discussed chemical analyses of plants at length, but Marchant omitted them from his descriptions.[16]

Dodart accepted many of Perrault's and Duclos's criteria for describing plants; he also learned from Marchant's experience of writing descriptions. He reaffirmed that the Academy's goal was to publish a description of every known plant. He agreed with Perrault and Duclos that the function of any description was to enable the reader to distinguish one plant from another. As a result, he limited descriptions to the parts of plants that served this purpose, or that helped to discover the uses of the plant, or that revealed "some particular industry of nature." When its surroundings affected the appearance of a plant, these also were to be indicated. Because the botanical vocabulary of the French language was limited, Dodart warned, academicians would coin words or borrow them from the vernacular.[17]

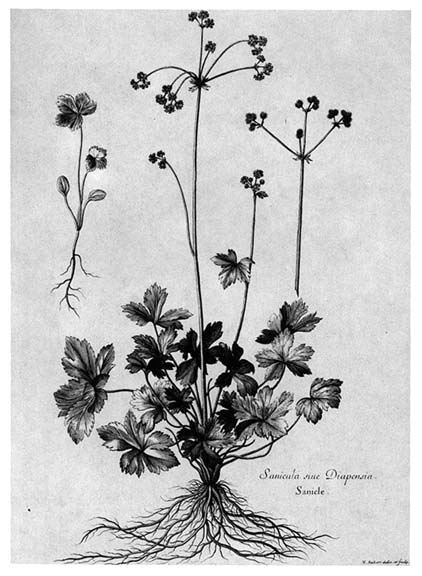

More important, the Academy was now able to commission its own drawings from life. Many of the illustrations in Marchant's Descriptions de quelques plantes nouvelles were copied from the duke's watercolors. But Dodart's Mémoires des plantes announced that the king's patronage would henceforth suffice to obtain engravings of the highest scientific standard; the Academy's artists would refer to the watercolors only if Marchant could not grow certain rare plants. The Academy would take the utmost pains to obtain accurate and detailed pictures. The engravers drew delicate parts or very small plants with the help of a microscope, and they used etchings (eau forte ) rather than line engravings (taille-douce ) to suggest shades of color (figs. 1-12). Instructions to the artists reflected Perrault's and Duclos's recommendations. Thus, illustrations would indicate the actual or relative size of each plant and portray the appearance of the plant in the earth (figs. 3, 4). They would also include a picture of the young plant, "whenever it first appears in a shape different enough to make it difficult to recognize" (fig. 5).[18]

Familiar with his colleagues' views, Dodart adopted them selectively, usually siding with Perrault. He rejected all known systems of classification, washing the Academy's collective hands of the problem that exercised Morison and Ray and whose solution later brought international fame to Tournefort.[19] Dodart shared Perrault's interest in testing methods of propagating plants and wanted to disprove the Theophrastean claim that plants could be propagated from their saps alone. Both Perrault and Dodart also

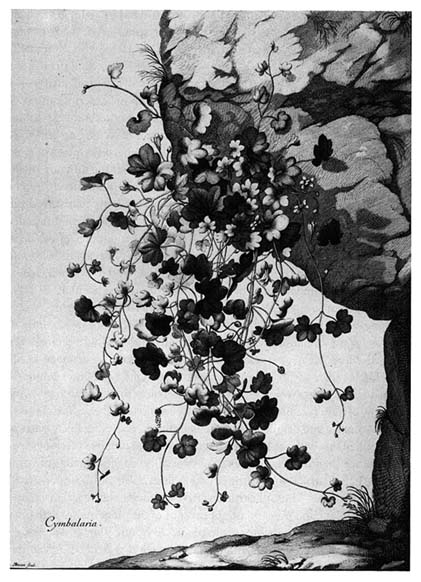

Fig.3.

Cymbalaria. (From Estampes ; engraved by Bosse;

photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

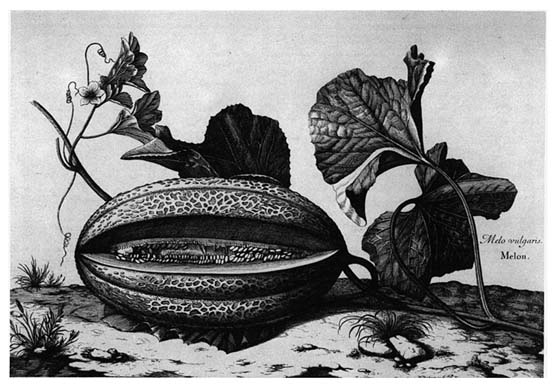

Fig. 4.

Melo vulgaris/Melon. (From Estampes ; engraved by Robert;

photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

Fig. 5.

Sanicula, sive Diapensia/Sanicle. (From Estampes ; drawn and

engraved by Robert; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

hoped the Academy could displace superstitions with observations, in that way teaching the public and raising the standard of knowledge about nature.[20]

Despite such similarities of approach and interest, the Mémoires des plantes was in certain respects Dodart's personal statement about the natural history. First, he affirmed the Baconian principle that one should not "condemn as false something that has not succeeded for oneself, but [instead] simply report the methods and results of one's experiments."[21] Dodart presented the Academy's raw findings, without hypotheses or conclusions. Duclos and Perrault, in contrast, expected the natural history to go beyond mere reports of experiment and difficulty. Second, Dodart introduced plant physiology into the natural history by including an explanation of how a plant grew, perhaps as an analogy with natural histories of animals that reported the development of the chick in the egg. He remained purist enough to exclude nutrition or the movement of sap from the natural history, but the cultivation of plants lent itself to analyses of germination and soils.[22] Whether or not Dodart intentionally challenged traditional definitions, no other academician had included these subjects in the natural history.

In ten years four academicians — Huygens, Perrault, Duclos, and Dodart — designed research on plants. They were inspired by earlier natural histories and by a well-established dichotomy between natural history and natural philosophy.[23] As work began in earnest, old distinctions were eroded and the fate of the project was irremediably altered by the addition of chemical analysis. Before considering the effects of that decision, however, the progress of research in all its aspects — cultivation, description, illustration, and chemical analysis — must be reviewed.

Research for the Natural History

Academicians began work soon after Perrault proposed the natural history, but they needed plants for study. Perrault called for an "Academic Garden"[24] and by the 1670s Nicolas Marchant had commandeered part of the vast and unused territory of the Jardin royal for the Academy. This plot became known as the petit jardin and was formally recognized as belonging to the Academy.[25] In it Marchant and his son cultivated seeds from all over the world, collected by friends, acquaintances, and colleagues.[26]

After cultivating a plant, the Marchants described it, gave it to the illustrators, and if there was enough supplied it to Bourdelin for analysis.[27]

Jean Marchant preserved unusual specimens in his cabinet at the Jardin royal.[28] The final description, however, was the collective business of the Academy.[29] While the Marchants read their preliminary drafts aloud at meetings, academicians looked at the plant and proposed improvements; during the spring of 1668 Nicolas Marchant and Duclos debated correct descriptive style.[30] The Academy soon approved a division of labor that persisted for several decades. The Marchants grew plants, not just rare ones, in order to explain their cultivation and development.[31] Bourdelin analyzed plants chemically,[32] while Dodart and the Marchants compiled comprehensive nomenclatures of each plant and wrote descriptions.[33] Finally, the artists drew and engraved the plants, working from life whenever possible. These patterns of work survived changes in the directorship, making the natural history of plants a team project that reflected the ideas and work of several academicians. It was too ambitious an undertaking for any one savant.

Illustrations occupied a prominent place in the natural history and in publicity for the Academy. Engravings of rare plants accompanied Marchant's Descriptions de quelques plantes nouvelles and Dodart's Mémoires des plantes ; they were printed in an expensive folio format that would appeal to the king and encourage him to continue publishing the Academy's work. With the same purpose in mind, academicians showed Louis drawings of plants when he visited the Library in 1681.[34] Illustrations were essential because even the clearest description could not identify a plant so well as a picture of it. John Ray had likened "a history of plants without figures" to "a book of geography without maps," and regretted that engravings were beyond his means; Robert Morison impoverished himself to illustrate his text.[35] Royal funding gave the Academy a distinct advantage over savants who lacked patronage, because the Academy could spend substantial sums on illustrations.

Three engravers — Abraham Bosse, Nicolas Robert, and Louis Claude de Chastillon — shared the work, which cost more than 25,000 livres (table 8)from 1668 through 1699.[36] Like so much of the Academy's program, this too suffered from Louis's wars, and Colbert stopped paying for engravings in 1681, despite the pleas of academicians.[37] Louvois reinstated funding for the Academy's illustrations and Pontchartrain continued it, concentrating his resources on Tournefort's Élémens and finally publishing all of the Academy's engravings of plants in the early eighteenth century.[38] But many of the plants that Bosse, Robert, and Chastillon drew were never engraved.[39]

Academicians tried, not altogether successfully, to hold Bosse, Robert,

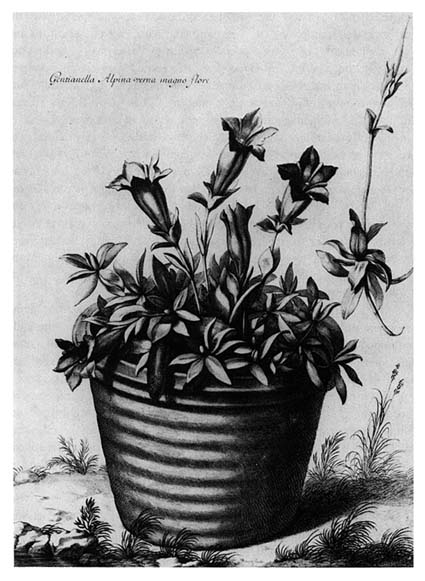

Fig. 6.

Gentianella alpina verna magno flore. (From Estampes; engraved

by Bosse; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

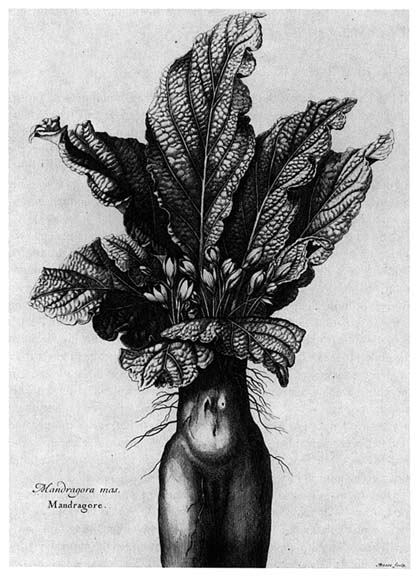

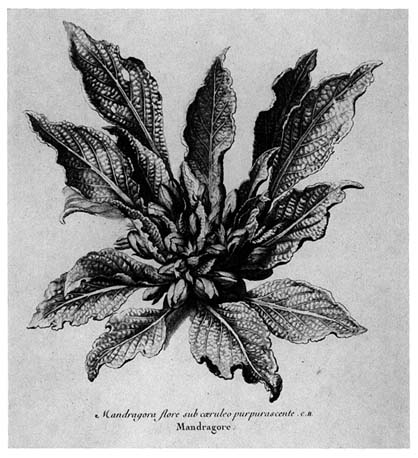

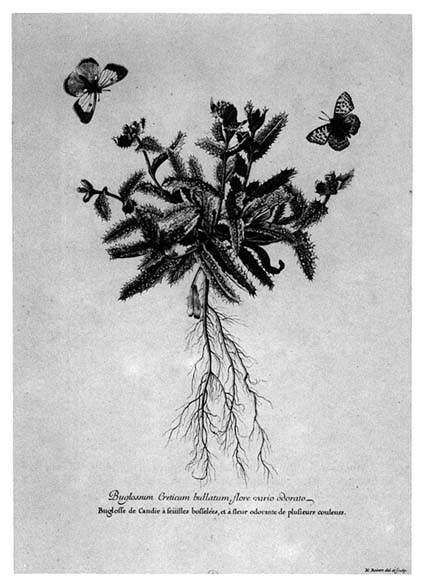

and Chastillon to a new standard of scientific accuracy. They supervised the artists closely, comparing drawings and engravings with descriptions and actual plants.[40] They were especially critical of Bosse's work, finding not one of the flowers of Cymbalaria (fig. 3) accurate,[41] protesting the superfluous branch and pot in the picture of Gentianella (fig. 6),[42] and deriding his anthropomorphic Mandragora mas (fig. 7) as "a ridiculous affectation."[43] Chastillon misrepresented the proportions of the leaves to the plant in depicting the mimosa (fig. 1).[44] Microscope and loupe were called for to correct certain features.[45] Extraneous details such as butterflies (fig. 9)[46] and birds marred some illustrations. Chinese characters (fig. 12) betray an engraving taken from an illustration rather than life. Many pictures lacked roots, seeds, and proper scientific names.[47] For reasons of economy, the size of engravings was reduced under Louvois,[48] but for reasons of accuracy, a picture of the seed, flower, and other parts of plants was added to some illustrations (figs. 1, 2).[49] These problems slowed the work, and the engravings as published in 1701 were far from representing the standards of the Academy.

Bourdelin performed the chemical analyses, which the entire Academy reviewed and Dodart interpreted. As soon as the laboratory was minimally equipped in June 1668 Bourdelin began distilling plants,[50] which remained his major occupation until his death in 1699. Indeed, Bourdelin analyzed more plants than were described or illustrated and his reports became a regular fixture at meetings.[51] It took large quantities — a hundred livres according to Dodart's estimate — to analyze a plant thoroughly.[52] Plants that did not grow around Paris.[53] were cultivated in the Jardin royal or were purchased.[54] From Bourdelin's findings Dodart tried to discern the basic composition of plants. Interpretation depended on minutiae, and Dodart struggled unsuccessfully to extract from overly plentiful details the generalizations that would justify Bourdelin's labors.[55]

Academicians collaborated in planning and researching the natural history of plants, and this cooperative spirit was a matter of pride. Four members designed the research, four carried it out, and many others contributed at assemblies. Bourdelin, Nicolas and Jean Marchant, and Dodart were the principal collaborators. Although Perrault proposed the project in 1668, he worked primarily on the natural history of animals, which he had suggested at the same time. But it is odd that Duclos, who directed the project in the 1660s and early 1670s, contributed very little afterwards to its completion. The explanation does not lie wholly in Duclos's preference for other work, such as his study of mineral waters, which distracted him from the natural history of plants.[56] Rather, his

disassociation from the natural history was involuntary, the result of a struggle over who would edit the project.

Editorial Rivalry

Duclos's nemesis was the young Dodart, physician and protégé of Perrault, whose association with the Academy began in 1671.[57] Dodart quickly took a position of responsibility and leadership. He was instrumental in reinstating the practice of keeping minutes and in reviving the Academy during an early slump.[58] Within five years he had become director of the natural history of plants, and his Mémoires des plantes reveals his control rather than Duclos's. With Perrault's protection, his influence transcended his lack of seniority in the Academy.

Dodart rose at the expense of Duclos. Director of the botanical project and leading theoretician of chemical research at the Academy in the 1660s, Duclos found his authority diminished during the 1670s. The minutes chart this decline. In his heyday from 1667 until 1669, Duclos read an average of more than three substantial papers a year — on topics ranging from coagulation and solvents to a detailed analysis of one of Boyle's books — filling roughly five hundred pages of minutes. During his decline in the period from 1675 to 1683, Duclos presented an average of fewer than two papers a year, and these fill at most twenty-odd pages in the minutes. In the 1660s Duclos dominated chemical and botanical planning with his long-range proposals, the status symbols that were the preserve of members who controlled the facilities and supervised others. Thereafter, this became Dodart's prerogative. Duclos conducted only his personal research by the mid-1670s, while Dodart supervised some of the work in chemistry and directed the natural history of plants. Why did this happen?

Dodart's interests and relative youth made him a plausible replacement for Duclos as director of the natural history of plants. Duclos's papers focused on experimental or theoretical chemistry, while Dodart was fascinated with all natural phenomena.[59] Dodart supervised the natural history and chemical analysis of plants energetically.[60] Duclos, however, was preoccupied with his books on mineral waters and on alchemical subjects. Since Duclos was at least thirty-five years older than Dodart, his flagging energy and waning interest in all but his favorite projects make Dodart's assumption of the natural history of plants even more understandable. Yet Duclos did not happily relinquish his responsibility to the new junior colleague. Thus Dodart's interests and qualifications do not explain a succession that was forced rather than amicable.

Fig. 7.

Mandragora mas/Mandragore. (From Estampes; engraved

by Bosse; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

Fig. 8.

Mandragora flore sub caeruleo purpurascente, C.B./Mandragore. (From

Estampes; artist unknown; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

Fig. 9.

Buglossum creticum bullatum, flore vario odorato/Buglosse de Candie à feuilles

bosselées, et à fleur odorante de plusieurs couleurs. (From Estampes; drawn

and engraved by Robert; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

Duclos's espousal of Platonist and Paracelsian views and his lifelong alchemical study complete the explanation. He made no secret of these interests, which he presented to his colleagues in several papers during the 1660s. For a while the Academy tolerated Duclos's pursuits. Later it feared embarrassment should his leanings become associated in the public mind with the institution itself, and academicians went so far as to refuse Duclos permission to publish one of his books.[61]

Duclos deeply resented Dodart's usurpation and counterattacked by maligning his editorial, scholarly, and collegial integrity. He accused Dodart of writing badly and reproached him for ignorance and careless reasoning. He unfairly denied that the Academy asked Dodart to write the Mémoires des plantes . Most important, Duclos criticized Dodart for misrepresenting the Academy. Dodart, he claimed, attributed ideas improperly to the Academy, represented his own views as those of his colleagues, portrayed the opinions of a few as if all academicians accepted them, and misrepresented theories he did not share. Duclos claimed that Dodart failed to collaborate with other academicians who had directed the research. The truth was that Dodart had simply rejected many of Duclos's views. Finally, Duclos was appalled because Dodart's book elaborated methodological issues instead of presenting conclusions about the nature of plants. At the heart of their disagreement was an argument about the purpose of analyzing plants chemically: Duclos had anticipated substantial insights into the nature of plants, but Dodart found the analyses more beneficial for medicine.[62] Duclos's animosity, therefore, had both personal and professional aspects; the latter, which focused on the purposes of chemical analysis, will become clearer in the following chapter.

Dodart certainly used his editorial power to alter the project, and his Mémoires des plantes was a very different book from anything Perrault or Duclos had conceived. It enumerated the obstacles to carrying out Duclos's instructions of 1668. In contrast, Marchant's Descriptions de quelques plantes nouvelles simply ignored them. Duclos had hoped to establish from the chemical analyses a theory with practical applications, but Dodart declared such efforts fruitless and advocated a more pragmatic use of Bourdelin's findings.[63] It is not surprising therefore that Duclos perceived the book as a disavowal of his views.[64]

Conclusion

Dodart claimed that the Mémoires des plantes was the first stage of a more comprehensive study of plants and a showpiece of collaboration.[65]

Both claims were only partly correct. The Academy never published the natural history of plants as conceived, and its cooperative research foundered on personal and substantial quarrels. Several problems imperiled the project. There was no perfect correspondence between descriptions and illustrations, with some plants described but not engraved and others engraved but not described. Funding was inadequate. Academicians disagreed about the style and content of descriptions, had to invent a botanical vernacular, and lacked simple criteria for selecting plants. Despite repeated revisions, illustrations remained inadequate and descriptions did not reflect the Academy's recommendations. The surviving notes reveal disagreements and delays in correcting problems.[66]

Still another issue — the chemical analysis of plants — divided academicians and jeopardized the natural history. Academicians' expectations and difficulties form the subject of the next chapter, which explains why they persisted with such recalcitrant research.