The Lost Second Installment

![]() Dodart

Dodart ![]() wanted to publish essays on plants annually, or at least in regular installments. He thought that the second volume of his natural history of plants should set out generalizations and exceptions and describe individual plants.[1] Hoping that the public would share his interest in explaining

wanted to publish essays on plants annually, or at least in regular installments. He thought that the second volume of his natural history of plants should set out generalizations and exceptions and describe individual plants.[1] Hoping that the public would share his interest in explaining

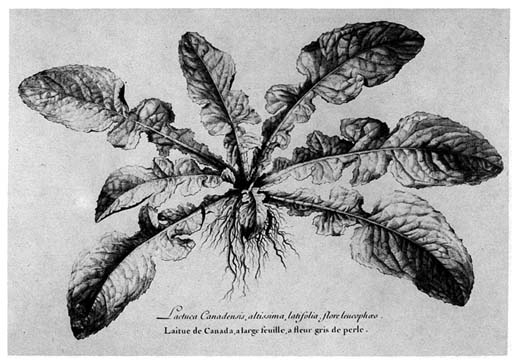

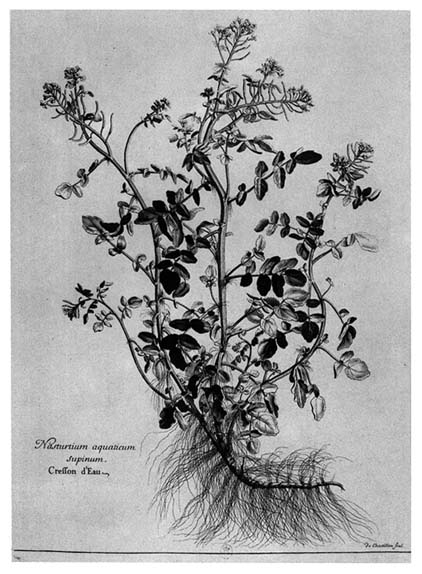

nutrition, he planned to write not about the rare plants that intrigued Nicolas Marchant but about homely vegetables that formed part of the diet, such as "coriander, lettuce, wild and domesticated chicory, watercress, etc." (figs. 10, 11).[2] This concern with nutrition greatly expanded the work. From 1676 to April 1678, Bourdelin analyzed more than four hundred and fifty plants and animals for ![]() Dodart

Dodart ![]() . In the spring of 1679, Jean Marchant sowed more than four hundred different seeds from France and abroad, "with the object of describing them for the general history of plants."[3]

. In the spring of 1679, Jean Marchant sowed more than four hundred different seeds from France and abroad, "with the object of describing them for the general history of plants."[3]

Between August 1680 and mid-June 1681, ![]() Dodart

Dodart ![]() wrote the second part of the natural history of plants and prepared three other treatises for publication. But he fell victim to a dreadful scholarly accident. All of his treatises — the second part of the natural history of plants and the works on medicine, natural philosophy, and plants — were stolen from him. Du Hamel had to explain the loss to Colbert:

wrote the second part of the natural history of plants and prepared three other treatises for publication. But he fell victim to a dreadful scholarly accident. All of his treatises — the second part of the natural history of plants and the works on medicine, natural philosophy, and plants — were stolen from him. Du Hamel had to explain the loss to Colbert:

…all these treatises which ought to have composed a good volume were stolen from him on his way into Paris, where he was bringing them in order to complete them for the printer; and since all the efforts which he has made to recover them have been futile, he has been obliged to redo the two most important of these treatises, and to collect from his papers anything that he can find that will help him rewrite the other works.[4]

The highwaymen were probably so disappointed with their worthless booty that they threw it away, but ![]() Dodart

Dodart ![]() had to spend the rest of the year rewriting the stolen treatises.[5] By mid-December 1681 Du Hamel could report that among the books ready for publication were

had to spend the rest of the year rewriting the stolen treatises.[5] By mid-December 1681 Du Hamel could report that among the books ready for publication were ![]() Dodart's

Dodart's ![]() "Deuxième partie du projet de l'histoire des plantes" and "Analyses des plantes," and Marchant's "Environ 200 descriptions de plantes gravées."[6] The first two were apparently reconstructions of the stolen books. By December 1681, therefore, despite the theft of

"Deuxième partie du projet de l'histoire des plantes" and "Analyses des plantes," and Marchant's "Environ 200 descriptions de plantes gravées."[6] The first two were apparently reconstructions of the stolen books. By December 1681, therefore, despite the theft of ![]() Dodart's

Dodart's ![]() manuscripts, the Academy was ready to publish three volumes pertaining to the natural history.

manuscripts, the Academy was ready to publish three volumes pertaining to the natural history.

Why were these works never published? It cannot have been disputes about distillation that delayed publication, for by separating the "Deuxième partie" and the "Analyses des plantes," ![]() Dodart

Dodart ![]() had insulated the uncontroversial aspects of the Academy's work from contamination by chemical analyses of uncertain merit. Blame for the failure to publish lies partly with the academicians and partly with their patron. Many of Marchant's descriptions were inconsistent with the plates or with earlier treatises, and discrepancies had to be resolved before publication. Financial reasons also delayed publication. Funding for the Academy diminished in the late 1670s, and in the 1680s Colbert still refused to release funds for

had insulated the uncontroversial aspects of the Academy's work from contamination by chemical analyses of uncertain merit. Blame for the failure to publish lies partly with the academicians and partly with their patron. Many of Marchant's descriptions were inconsistent with the plates or with earlier treatises, and discrepancies had to be resolved before publication. Financial reasons also delayed publication. Funding for the Academy diminished in the late 1670s, and in the 1680s Colbert still refused to release funds for

Fig. 10.

Lactuca canadensis, altissima, latifolia, flore leucophaeo/Laitue de Canada, à large feuille, à fleur

gris de perle. (From Estampes ; artist unknown; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

Fig. 11.

Nasturtium aquaticum supinum/Cresson d'eau. (From Estampes ; engraved

by Chastillon; photograph courtesy of Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.)

engravings despite persistent appeals from academicians. When the king visited the Academy at the Bibliothèque du roi in December 1681, academicians presented him a list of treatises ready for publication, to no avail. But these refusals must have been couched in encouraging terms, for academicians continued their work, and morale in the early 1680s was better than it had been a decade earlier. They lived on promises and persevered.[7]

Even the transition from Colbert's to Louvois's ministry did not at first disrupt work on the natural history of plants. During the first thirty months of Louvois's protectorship, work continued apace, especially on engravings, which Louvois had reinstigated. Louvois encouraged academicians to ready their work for print. His ministry marked closer ties between the Academy and the Jardin royal, especially with Fagon and Tournefort, whom Fagon took under his wing. Fagon chose plants for Chastillon to draw for the Academy's "Mémoire des plantes," and Louvois sponsored Tournefort's herborizations in the Iberian peninsula.[8] In the winter of 1684 the Company planned to work on roots, seeds, and woody parts of the plants that had been engraved, while Bourdelin continued his analyses.[9] In 1685 and 1686 ![]() Dodart

Dodart ![]() and Marchant concentrated on engravings and descriptions.[10] In 1685 Du Hamel believed that the Academy would soon publish a volume of the natural history of plants, for which many engravings were completed.[11] But after 1686, the grand botanical compendium was mentioned in the minutes only as a project of the past.

and Marchant concentrated on engravings and descriptions.[10] In 1685 Du Hamel believed that the Academy would soon publish a volume of the natural history of plants, for which many engravings were completed.[11] But after 1686, the grand botanical compendium was mentioned in the minutes only as a project of the past.