II—

Bombardment

If the general climate of cultural life was not friendly, the rebels found themselves little by little gaining allies in the intellectual community, largely because of the deepening crisis of the Depression. By 1932 it was generally understood that this economic and social disaster was not going to fade away. Artists and writers became increasingly interested in alternative social proposals, particularly leftist solutions. Manifestos on culture and crisis began to appear, signed by artists on both coasts, and study groups burgeoned, among them the Marxist John Reed Club.

The young painters were prepared to broaden their theoretical horizons under pressure from a turbulent society. One alluring source of a theory that could encompass social upheaval was right on their doorstep: the Mexican mural movement. For a seventeen-year-old boy, filled with conflicting impulses and feverishly trying to train himself for the great life of a painter, the firm rhetoric that accompanied reproductions of works by Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros in the art magazines was impressive. Jackson Pollock wrote excitedly to his brother in 1929 about a special issue of Creative Art that featured the Mexicans. He and Guston could read Orozco's declaration that the

"highest, the most logical, the purest and strongest form of painting is the mural. In this form alone, it is one with the other arts—with all the others. It is, too, the most disinterested form, for it cannot be made a matter of private gain; it cannot be hidden away for the benefit of a certain privileged few." When Orozco came in person to paint his mural Prometheus at Pomona College, the boys made a special trip to watch him at work.

David Alfaro Siqueiros arrived in Los Angeles in 1932 at the invitation of a local art school, the Chouinard Institute, to create a mural. Siqueiros's flamboyant personal style delighted his young admirers. He was, says Fletcher Martin, "a brilliant, eccentric, eloquent man, the most vivid personality I've ever met in my life."[1] When he came to Chouinard, "he formed a team consisting of himself and six assistants whom he called 'Mural Block Painters' and set them to paint a mural. The surface at his disposal was small and irregular—an outer wall 6 ́ 9 meters broken by three windows and a door. As the cement surface cracked almost immediately, Siqueiros decided to use spray guns, used for applying quick-drying paint to furniture and cars." Siqueiros's "assistants" changed daily, but a host of art students hung around constantly to listen to the master. His recent encounter, in 1931, with the Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein had filled him with an enthusiasm for psychology, chemistry, and above all photography. As he worked (for it was Siqueiros who really executed the work) he would discourse to his attentive audience. The Chouinard mural, appropriately enough, pictures a soapbox orator addressing workers who watch him from a tiered building. Siqueiros's close study of Renaissance murals was evident in the flattened, vertical composition and in the simplicity of his forms.

From Chouinard, Siqueiros moved to a site on Olvera Street in the center of Los Angeles, where he undertook an outdoor mural for the Plaza Arts Center. As it was his habit to work largely at night, Guston could occasionally observe him after his own day's work driving a truck was over. The Olvera Street project was enormous—eighteen feet high and eighty feet long. Its central image was of a Latin-looking figure being crucified while an American eagle hovers nearby. The controversy this mural incited was not to die until two years later when the city authorities whitewashed over its inflammatory message.

All this excitement coincided with the activities of the John Reed Club, which had been originally founded late in 1929 in New York as a Marxist study group but had gained adherents in other American

cities as the Depression worsened. The Club's 1932 draft manifesto soberly noted that:

Thousands of school-teachers, engineers, chemists, newspapermen and members of other professions are unemployed. The publishing business has suffered acutely from the economic crisis. Middle-class patrons are no longer able to buy paintings as they formerly did. The movies and theatres are discharging writers, actors and artists. And in the midst of this economic crisis, the middle-class intelligentsia, nauseated by the last war, sees another one, more barbarous still, on the horizon. They see the civilization in whose tenets they were nurtured going to pieces.…

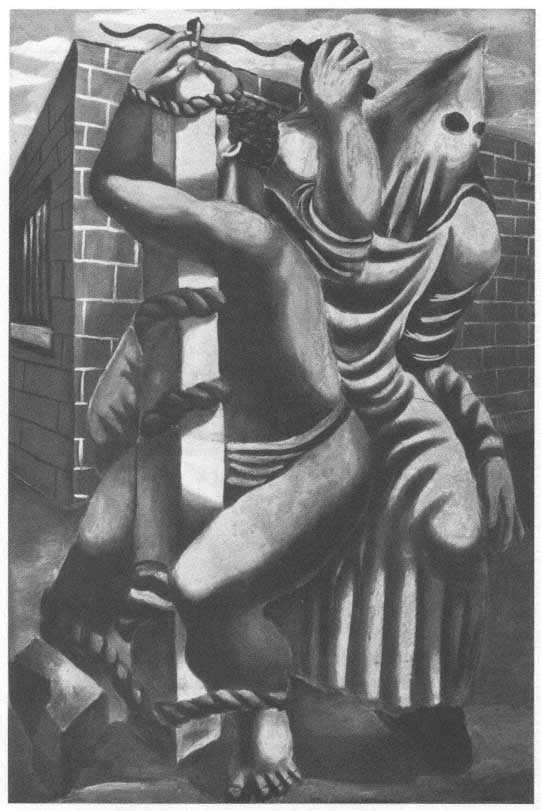

In late 1932 Guston, Kadish, Harold Lehman, and several of their friends decided to respond to the John Reed Club's call to "abandon decisively the treacherous illusion that art can exist for art's sake." They undertook to paint "portable" murals on the theme of the American Negro, who was seen by all liberal publications of the time as the victim of lynching and other barbarous practices. Guston's mural, based directly on accounts he had read of the trial of the Scottsboro boys, showed Ku Kluxers whipping a roped black man. The murals, executed on separate panels in a shed owned by a Mexican painter, Luis Arenal, were each about 6 ́ 8 feet in size and were painted in fresco on increasingly fine layers of sand and cement poured into wooden frames. This undertaking was to provide the young painters with the first confirmation of their suspicions that America was in a dangerous state of violent confusion. Early one morning a band of raiders, thought to be led by the chief of the Red Squad, a man called Hines, and abetted by members of the American Legion, entered the John Reed Club brandishing lead pipes and guns. They totally destroyed several murals and, as Guston recalls with a shudder, shot out the eyes and genitals of the figures in his completed work. An eyewitness came forward to say he had seen the police enter the premises, and the artists, almost all of them in their late teens, decided to sue. At the trial the judge looked with distaste upon these insurgent Americans, declared that the murals had been destroyed by parties unknown, and suggested that it was the painters themselves who had probably done it to call attention to their cause. This experience was Guston's first exposure to "justice" and intensified his inner debate as an artist. Forty years later he was still watching the issue of California

Fresco panel, 1930 or 1931.

law in the person of Nixon, whose "justice" Philip Guston has challenged in a suite of searing caricatures.

But caricature, during the high moment of true fresco painting in Guston's early career, was far from his intention. He was fired with the ambition to produce "the big wall" in a lofty symbolic style worthy of his Renaissance obsession. His concern with idealistic subjects remained, but his artistic ambitions went beyond simplistic formulas. When an older artist took an art-for-art's-sake position, saying he didn't care if a painter painted a flag with a swastika or hammer-and-sickle or fasces so long as it was well done, Guston replied scornfully that no artist would feel that way. But when he looked at Rivera's more bombastic works, he recoiled and sought again the magisterial calm of the murals of Masaccio and Piero della Francesca.

In April 1933 the nineteen-year-old Guston was one of fifty artists chosen from among the three hundred who submitted works to the Fourteenth Annual Exhibition at the Los Angeles Museum. He showed Mother and Child in the exhibition, which had firmly excluded the nature painters who had long dominated the local scene. Some two hundred artists thereupon protested "handiworks of mediocre charlatans and fashionable faddists."[2] Implicit in their attack was a hatred for the social implications in much of the work. "We raise our lances to defend the sacredness of art," they said. "Our ideals of true Americanism are endangered." Characteristically, these guardians of America associated modern art with foreigners and Bolshevism. They were deeply alarmed to find subjects made visible by the Depression represented soberly by the young modernists. Newspaper commentaries stressed the New Deal bias of the artists, and a large public thus became aware of the political aspects of recent Los Angeles art.

The climate was becoming highly charged by this time and not even artists were immune to New Deal proposals. It was in the year 1933 that the National Legion of Decency was formed to purge Hollywood of its purportedly leftist bias. This was also the year that George Biddle laid the groundwork for the forthcoming government projects for artists, writing to his old school friend Franklin D. Roosevelt that "the younger artists of America are conscious as they never have been of the social revolution that our country and civilization are going through and they would be eager to express these ideals in a permanent art form.…"[3] Biddle had in mind the prototype offered by the Mexican government, which had paid artists to work at plasterers' wages "in order to express on the walls of the government buildings the social idea of the Mexican revolution."

The young artists eagerly welcomed the first government projects in California. They had assimilated enough knowledge from the Mexican muralists to undertake large wall spaces. They had responded with alacrity to the attacks of the local keepers of provincial esthetics, and they had been stimulated in innumerable ways to take a critical stand in the seething struggle between Right and Left. Guston in particular had kept his eye on Americana, the satirical journal that brought Gilbert Seldes and George Grosz together under the editorship of the eccentric Alexander King, who hoped to echo the extravagantly irreverent note that had once resounded throughout Germany in the journal Simplicissimus. Editorials, signed by "The Vigilantes," called for such measures as "Let's Shoot All the Old Men." The mores of America were illustrated in sharply satirical drawings (Guston remembers one issue in which every page carried a portrait of Hoover as an ass with a high collar) and in photomontages. One example was a suite of photographs of four student "demonstrations": the first three showing bloody street battles in Italy, Greece, and Germany, while the fourth pictured a well-dressed American student of the F. Scott Fitzgerald type "demonstrating" a vacuum cleaner to a pretty housewife with well-exposed legs.

Such visual critiques always interested Guston, who has never throughout his career stopped drawing pithy caricatures. But his greater aspiration still lay in the opportunity to master a great wall, and he was among the first young artists to be signed up, early in 1934, when California set up its first federally sponsored art project. Under the Civil Works Administration Arts Projects, he, Reuben Kadish, and Harold Lehman set to work to depict the history of crafts and trades from Egypt to the modern period on a 525-foot wall at the Frank Wiggins Trade School. This undertaking ended in a farcical quarrel with the federal administration that led to all the young artists being thrown off the job, but the tantalizing taste of possibilities set them dreaming of more congenial prospects.

Kadish, who had worked as Siqueiros's assistant in Los Angeles, decided to write him, in the faint hope that somewhere in Mexico there might be a wall for him and Guston. (Originally, Guston and Kadish had wanted to go to Italy to see the old frescoes, but when they went to the San Pedro docks and discovered how much it cost to go to Europe even on a tanker, they changed their destination, realizing that the main thing was to get out of Los Angeles.) Siqueiros answered by saying: Come, we'll find something.

"Philip quit his job

and bought a Ford coupe for twenty-three dollars," Kadish remembers, "and I cashed in a life-insurance policy. We also took along Jules Langsner, the poet, who had no money." When they got to Mexico City, they found that Siqueiros and Diego Rivera had already persuaded the University to offer a huge wall in Maximilian's former summer palace in Morelia, now a museum. "We'd already wrecked the car," Kadish recalls, "so we sent Phil to see the rector of the museum and two days later we got a telegram to come."

The sharp contrast in cultures struck the two young painters who had once been thrown out of high school for their activism. Coming from Los Angeles with its stubborn resistance to governmental support for the arts and its perpetual witch-hunting, Kadish and Guston had their first taste of the transplanted European tradition of support for the arts in high places. Since Guston's previous experiences with officialdom had all been disastrous, his interview with the rector of the University, and his subsequent encounters with high officials enthusiastically involved in the artistic life of the country, astonished him. The rector, he wrote, "runs the town culturally, is an art patron, the image of Lenin, and wants to make his city a modern Florence!"

Before going to Morelia, the boys went sightseeing. "I have seen the Pyramids of the Aztecs already, also temple of Quetzalcoatl. Been to bullfights, seen much Aztec sculpture and burned up my stomach with chili," Guston wrote to Harold Lehman from Mexico City on July 14, 1934. He also described his disappointment with the "much heralded Mexican Renaissance." He especially disliked the work of Rivera and at first was not even enthusiastic about Orozco, who "is an expressionist and dominated by emotion but at least is plastic now and then." It is clear in his initial response to the mural painters of Mexico that Guston's immersion in the Italian Renaissance remained his most important impetus. All the same, despite his deepening critical attitude, he was able to enjoy nights with Siqueiros and to respond to the verve of the old master:

He brought with him photos of his Argentine fresco and there is something! It is all done in airbrush and the painting may be shitty but he is experimenting with Kinetics! The shape of the room is half-cylinder shape [here a little sketch]. Huge, and he painted the floor also. Not a bit of space unpainted. Not being a flat plane on a wall, he had the problem of distortion. So he painted his nudes very distorted so that they would not appear distorted because of the peculiar shape of the

wall.…And tremendous movement. He composed it so that as the spectator moves the figures move and rotate with him…and he waves his hand and calls it merely a plastic exercise!

Once in Morelia, Guston and Kadish were given 1,024 square feet of virgin wall with the condition that they finish the commission, in true fresco, within four months. For this they got room, board, studio space, and all materials. On October 4, Guston reported that half the fresco had already been completed. "We are trying many new things and although much is more or less unsuccessful (as far as finished and refined style is concerned) I feel it to be a great experience and have profited greatly." He also reported that Orozco, who had come to town to begin his own fresco, approved their work, and added that he himself was painting easel paintings on the side. Extending his acquaintance in Mexico, he managed to get several portrait commissions, including a six-foot portrait head of Manuel Moreno Sánchez, a Supreme Court justice who sponsored a poetry magazine. He also did woodcuts and linoleum cuts for little magazines, participating in the expansive cultural life so at variance with his own.

All the while Guston's examination of his ideals as a painter was becoming more exacting. The presence of Jules Langsner, always a keen critical intelligence, stimulated Guston's sense of speculation. In November 1934, the trio went to Mexico City for the inauguration of the President, mainly because they had been delayed with the fresco by a lack of colors. Guston, in another letter, again registered his distaste for the expressionism of the Mexican masters, and reported spending his time studying Flemish and German primitives and some drawings by Michelangelo and Raphael in the museum. He bought many reproductions and mentioned with pleasure his finding some large, clear reproductions of Masaccio's frescoes.

When the Mexican project was completed, Kadish and Guston returned to California to undertake a commission together in Duarte, near Los Angeles, for the Treasury Department. But it was not long before Guston yielded to the urging of Sande McCoy (Pollock's brother who had taken back his father's original name) and Jackson himself, to set out for New York, where the WPA mural project was getting underway. "The best thing that is new with me," Guston wrote to Kadish, now in San Francisco, in a letter dated August 27, 1935, "is that I am going to New York in 3 weeks—about the 20th of September. I saw Tolegian [one of the Manual Arts group], he is here for a

few weeks—and he tells me that I will have a better chance to get on the project around this time than later in the fall." In the next sentence, he indicates how the pull away from studies of the classics to the Mexicans, to social realism, and to modernism had thrown young painters into a state of confusion: "Tolegian claims it is all Siqueiros' fault, his influence being quite opposite to clear and sober thought. Well, I shall find out for myself what the hell all this is about."

The "sober" influence in New York was Thomas Hart Benton, who had painted murals side by side with Orozco at the New School and had already offered liberal moral support to the young Jackson Pollock. Benton's twangy American background suited his followers at the Art Students League, who were eager to participate in the program of national self-discovery sponsored by the New Deal. The rapid series of events that brought artists together, not only under federal sponsorship but also into such political associations as the Artists' Congress, had created many disturbing problems in the lives of the young artists. From 1932 when there were fifteen million unemployed to 1935 when government programs were well underway, many conflicts of conscience suddenly appeared, interfering with esthetic commitments. In Los Angeles, some artists rose to denounce the Artists' Congress as a Marxist propaganda organ, while others defended it as the first mature association devoted to artistic interests. The staunchest defenders of the modern tradition, fearful of the tendentious aspects of the Congress's activities, sometimes found themselves unhappy bedfellows with outspoken Nazi sympathizers.

New York, from a distance, seemed less vulnerable to such bitter and hopeless theoretical wrangling. For one thing, more than half of the artists in all of the United States lived there, and, for another, it was there that the WPA projects were concentrated. Yet in reality the spiritual confusion and economic pressures were as intense in New York as in Los Angeles. A letter from Sande McCoy to Reuben Kadish, dated July 16, 1935, indicates the situation:

I am at a loss as to what position to take in regards to subject matter. To say nothing of the economic piss pot in which I find myself. Conditions here in general and particularly for the artist are certainly not improving in spite of the large gestures and bullshitting from Washington. There has been and is much talk of more Projects but it is the usual circle of procrastination if and when an artist is given a chance at a wall he is bound hard by a stinking Art Commission

headed by a super patriot…so as a result what few murals are being done are merely flat wall decorations of the lowest order, for instance Charlot was forced to paint a "mural" with the story of Costume as his subject!.…As for you and Phil coming here I think it the only sane thing to do even though there is a definite movement among artists to get out of New York into the mid-west and west to develop regional art (Wood-Iowa, Benton-Missouri, Curry-Kansas, etc.) but you must be prepared to face all kinds of odds for it is truly hard living here for one without means.…Incidentally, Rube, notice in the July 16 issue of New Masses that they plan to make the next quarterly issue a Revolutionary Art number.…

When Guston arrived in New York during the winter of 1935–36, he was not quite twenty-three years old, but he had already accumulated a store of experience as a professional artist, above all as a muralist, which enabled him to move quickly into the heart of artistic activities. Staying first with Pollock and Sande McCoy in their loft at 46 East 8th Street, and later in a small loft on Christopher Street, Guston adapted rapidly to the ways of New York's artistic community. He knew what he wanted: he wanted to paint large walls, and he wanted to develop as an easel painter in his free time. He wanted to challenge New York with the grand Renaissance manner.

The first step was to get on the mural project, which did not prove difficult for Guston. In the beginning he spent nearly a year doing large cartoons on a commission for the Kings County Hospital, which ultimately rejected them. He met James Brooks, who had come up from Texas to study at the Art Students League and who at first was doing lettering in the applied arts division of the WPA. Brooks had just won a competition for a mural and spent some time working on cartoons in Sande McCoy's loft. He was a mild-mannered but intense young artist whose interests paralleled Guston's. They both worried about stylistic choices and about the obligation to uphold the modern tradition in circumstances that were becoming increasingly difficult. When the Pollock brothers, who were at the time under the sway of Benton, Picasso, and Orozco, joined Brooks and Guston in the evenings, they often thrashed out the esthetic conflicts that were growing more severe in the late 1930s. Orozco, Brooks recalls, spoke very well about Giotto; when he lectured at the New School and at the Artists' Union, they would attend and afterward discuss the lecture all night.

In 1937 Guston married Musa McKim and took a loft on 22nd

Street near Fifth Avenue. Brooks by this time was living on 21st Street. The two men partook sparingly of the multifarious activities engaging artists in those days. When the Artists' Union, which had a cultural committee, had its weekly meetings, the two young artists would usually attend, but they did not become deeply involved, according to Brooks, who laughs about the unceasing political wrangling. "I can remember trying to get a well-known analyst to speak at the Artists' Union. Before he answered, he had to know: are they Stalinists or Trotskyites?"[4] Nevertheless, Brooks recalls the "strong tide" that swept through the studios. The thing was to get a wall, and the wall should bear a social message. Not even the most vanguard artists on the project doubted that the function of murals was social.

In a sense, though, it was a quiet life. It was the first time these artists had ever had a chance to work exclusively as artists in the United States. Both Guston and Brooks had known the harassing circumstances of separating their lives into working for a living and working to become better artists. Both had a need to concentrate. "We'd work like hell," Brooks recalls. "All day we'd work on cartoons or murals, and at night we worked from a model." They often met in their studios late at night for quiet talk or to play music. Guston played the mandolin, Brooks the recorder. They listened to jazz records once in a while, or went to the movies, which were still a great lure for Guston. Brooks remembers one day standing in line with Guston waiting for their paychecks. They debated going to the movies but then agreed that they would do better to go home and work. It was an Olivia de Havilland film and after parting for their respective studios, both doubled back secretly to see it. Coming out, they ran into each other.

More often they took their recreation in the stimulating atmosphere of the Federal Theater, which Guston recalls with enthusiasm. The WPA had quickly evolved into a confraternity of all artists in all the arts, and anything worth seeing at the theater could find a natural audience in those on the rolls of the project. Despite the considerable bickering and conflicts with the administration, there was a camaraderie among artists and intellectuals during the 1930s that has never since been equaled in the United States. It was natural for a young artist eager for a cultural endowment to gravitate to this theater, so singularly experimental in the mid-1930s. Wherever there was high ambition, artistically expressed, there was a sense of belonging, or, as they liked to say in those days, of solidarity.

For Guston, who would later evince great interest in the masque, and who has at times spoken of his paintings as a species of theater, the great theatrical experiments of the mid-1930s were memorable. He could easily relate to the Living Newspaper —a revue in which actual topics were enacted on the stage, frequently using quotations from the day's news—and to the famous musical Pins and Needles sponsored by the ILGWU. Still more exciting to him was the modernization of the formal theater. The fact that he remembers Orson Welles's Doctor Faustus, produced in street clothes, and his extravagant Julius Caesar, and, above all, Marc Blitzstein's The Cradle Will Rock, which Aaron Copland called the first American opera making "truly indigenous opera possible,"[5] points to Guston's consistent interest in the problem of using traditional forms in fresh ways.

The production of Blitzstein's opera, with its unconventional motif of a steel strike, in many ways epitomizes the experience of the 1930s. The opera was beset with problems from the start. The hostility of Congress to the arts projects had been growing, and the Hearst press had been assiduously fanning public prejudice. Since theater was more visible than most of the other arts projects, the watchdog committees in Congress had set themselves the task of destroying dramatic projects first. The guiding spirit in the remarkable theater network extending throughout the country was a vivid and highly intelligent former professor, Hallie Flanagan, who would not compromise her high standards. Warned by friendly New Deal cabinet members that the Living Newspaper was particularly galling to the legislators, she

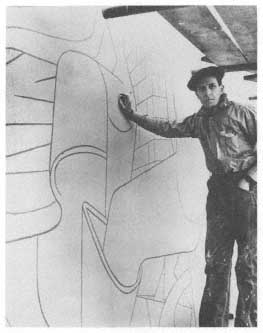

Guston on the scaffold of his WPA mural, 1937.

nonetheless attempted to brazen it out, calling upon a galaxy of enlightened dignitaries to fight for the project. But it was to be a losing struggle, and the theater project was the first to be scuttled when the reactionaries got the upper hand.

The unorthodox opera, for which Flanagan had hired John Houseman as producer and Orson Welles as director, was bound to irritate the theater's Washington enemies. For one thing, its theme was particularly timely and threatening. In 1937 the CIO succeeded in organizing General Motors and U. S. Steel, but the powers known as "Little Steel" resisted. Bitter strikes were underway when this opera, with its sympathetic view of union organizers and its stern caricatures of capitalists and police, went into rehearsal. Various forms of censorship were covertly initiated in Washington. Flanagan fought back by asking Archibald MacLeish and Virgil Thomson to intervene. After the production was well underway and hundreds of seats had been sold in advance, orders came from Washington that no opening could take place before the beginning of the new fiscal year. A last-ditch campaign in Washington failed to clear the air, and on opening night word came through that the performance was canceled.

All of the struggles during the months preceding had been widely broadcast among artists on the project, for it was an ominous warning of future tactics by the Right against all the arts projects. Moreover, Welles was already celebrated as a genius of the theater. Many artists were present for opening night, Guston at the invitation of Marc Blitzstein himself. They gathered at the Maxine Elliott Theatre, where they were met by Orson Welles, who announced the government's ban and declared his determination that the show would go on. He had just succeeded in renting another theater twenty blocks north at 58th Street and Seventh Avenue. He asked the audience and actors to join him there, and more than six hundred exhilarated spectators embarked on a historic march. Meanwhile, Welles and Blitzstein negotiated hastily with actors and musicians. It was decided that the actors would scatter themselves in the audience so as not to violate Equity orders forbidding participation in unauthorized presentations. As for the musicians, no compromise could be found and Blitzstein frantically tracked down a piano and played the entire score from the stage.

Aside from the natural excitement the exodus had produced, there was an extraordinary effect produced when the singers and actors rose from the audience to take their roles. Guston still vividly remembers Will Gear playing Mr. Mister, the steeltown owner, and Howard da Silva as the union organizer. The brilliant evening was not overlooked

by Washington. Shortly afterward, Flanagan's Federal Theater Project came under the scrutiny of the Dies Committee (predecessor of the House Un-American Activities Committee), which effectively killed it. The specter of a "Communist menace" became more pronounced as reactionary congressmen felt their power growing, and investigations of artists became routine during the late 1930s. Not even the New Deal officials most sympathetic to WPA ideals could prevent the gradual economic strangulation carried out by their opponents, who controlled the purse strings in Congress.

The sense of embattlement shared by all those in the artistic professions grew increasingly sharp as the world moved toward the Second World War. Already Mussolini and Hitler had made their intentions clear and many of the artists were among those well aware of the impending disaster. At the First American Artists' Congress in February 1936, Lewis Mumford spoke of "what is plainly a world catastrophe" and urged his listeners to meet the "emergency" with a determined resistance to the forces that are bringing on war and a conscious struggle against Fascism. At the same meeting Stuart Davis warned his colleagues that the press, which referred to artists on government projects as "Hobohemian chiselers" and "ingrates," was part of a general drive by vested interests to establish a regime founded on the repression of liberties. He too saw the urgent need for artists to resist war and Fascism. Speaker after speaker spoke uneasily of the world situation and its potential disasters for the newly established federal programs. Soon after, when the Spanish Civil War erupted, issues became even more urgent. Artists who had visited Siqueiros's experimental mural workshop on Union Square bade him good-bye as he went off to Spain to fight with the Loyalists. They attended rallies to hear such luminaries as André Malraux beg for their support in Spain. Guston painted Bombardment, an emotional commentary on the Spanish Civil War in tondo form, which was exhibited first in a show of the League Against War and Fascism and later at the Whitney Museum in its 1938 annual. Guston rolled the painting all the way from his studio to 8th Street for this first showing in an official place.

In spite of the overwhelming spirit of concern and ethical commitment to causes, the artistic life of New York City was by no means monolithic. Guston very quickly found colleagues who had as many misgivings as he did about the increasingly tendentious tone in contemporary American art. In 1938 he was twenty-five years old and had already begun to question his own commitment to the Renaissance

Philip Guston and Musa McKim at a Spanish Civil War rally, Union

Square, 1937.

vision. His questioning was deepened by contact with artists who had carefully sorted out their own positions and had chosen to work in the modern modes originating largely in France.

One of the firmest upholders of the abstract tradition was Burgoyne Diller, who in 1935 had been appointed head of the mural division of the Federal Art Project where he was Guston's supervisor. Diller was an early devotee of van Doesburg, Mondrian, and Vantongerloo, and by 1932 he had become permanently committed to total abstraction. As supervisor of the mural division, he tried to encourage his younger colleagues to experiment, and he was always quick to recognize talent regardless of the artist's style. Bohemian in his mode of existence, Diller was a magnetic force for Guston. He lived nearby, on 27th Street, in a basement apartment, and the first time Guston visited him, Diller received him wearing an overcoat instead of a bathrobe, a small detail that delighted Guston enough to repeat it to his friend James Brooks. Guston had endless discussions about modern art with the gentlemanly Diller. Guston remembers that he would say things like "Well, you're good in the ancient manner." But his knowledgeable discourse on recent trends in Paris aroused Guston's doubts. These were further inflamed by his conversations with other artists he met on the Project, among them Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, and Stuart Davis. At this time Davis was a strong figure whose reputation as a militant radical was matched by his reputation as one of America's best modern painters. While Guston was working on the Kings County Hospital cartoons in a loft provided by the project, Davis was

working in the next bay on a mural for the radio station WNYC. Guston used to watch Davis through a crack in the partition and was impressed by the pounds of cadmium orange, blue, and black that he so liberally squeezed out. "He would mount his scaffold, lavishly spread paint on large areas with a large palette knife, step down, and look at the results for a while in his suspenders smoking his cigar. Then he would mount his ladder again and scrape the whole thing off onto the floor. I remember how impressed I was by this lavish use of paint, and by his willingness to change in the process while I, in my bay, still under the spell of the Renaissance, was laboriously working on my big cartoon."

Davis, and most of the other artists whom Guston took seriously, were deeply aware of the force of Cubism as an appropriate contemporary pictorial idiom. All of them were striving desperately to reconcile their presence within the socially oriented framework of the WPA and their personal longing to participate in the great tide of modern art. Gorky, who himself had many private conflicts, looked at Guston's huge cartoons, strongly modeled in the Mantegna tradition, and told him, "Never mind, just stay there, don't do flat painting." But flat painting was a subject of constant discussion, particularly between Brooks and Guston, who shared certain ideas about style at that time. (A mural Brooks did at the Woodside Public Library in New York shows their stylistic affinities: it is a choreographically composed battle, in which the figures are modeled broadly, their limbs greatly simplified, and their surroundings depicted like stage settings.)

Guston's intense and elaborate conversations with his fellow artists were augmented by strong visual experiences. A regular haunt of all ambitious painters was the A. E. Gallatin Collection, then housed in a ground-floor study hall of New York University at Washington Square. Gallatin had formed a collection of European vanguard painting during the 1920s, and he continued to add to the collection during the following decade. Guston examined the drawings and paintings closely, with particular attention to two major works: Picasso's Three Musicians and Léger's The City. Both satisfied Guston's innate appetite for the grand and complex composition—an important aspect of the Renaissance tradition—and both successfully restated that tradition in modern language. Léger's masterwork could easily be associated with the grand "machines" of the old masters, while Picasso's intricate composition, with its witty use of overlapping flat planes, set Guston's mind to challenging his own assumptions.

His concourse with Diller had suggested the possibility of dropping "subject matter" altogether and becoming "pure." But his temperament resisted, and he sought answers elsewhere. He studied the large de Chirico exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1936 (where he saw the master himself repainting feverishly before the opening); he went to see paintings by Mondrian and Miró, and Cubist works by Picasso whenever they were exhibited; and in 1939 he saw Guernica, whose rearing white horse made an indelible impression on him.

These experiences fed Guston's perpetual debate with himself, and toward the end of 1938 he had, for the moment, eschewed his exclusively Renaissance position. "I became aware of the total picture space—the total picture plane, that is—as against just using volumes in an empty space." His encounter with Léger's The City revived his interest in Piero and Uccello, and he began to see Cubism as a modern extension of their complex rhythms. Such thoughts were germinating rapidly for Guston when he received his first important mural commission in 1939 for the WPA Building at the New York World's Fair.

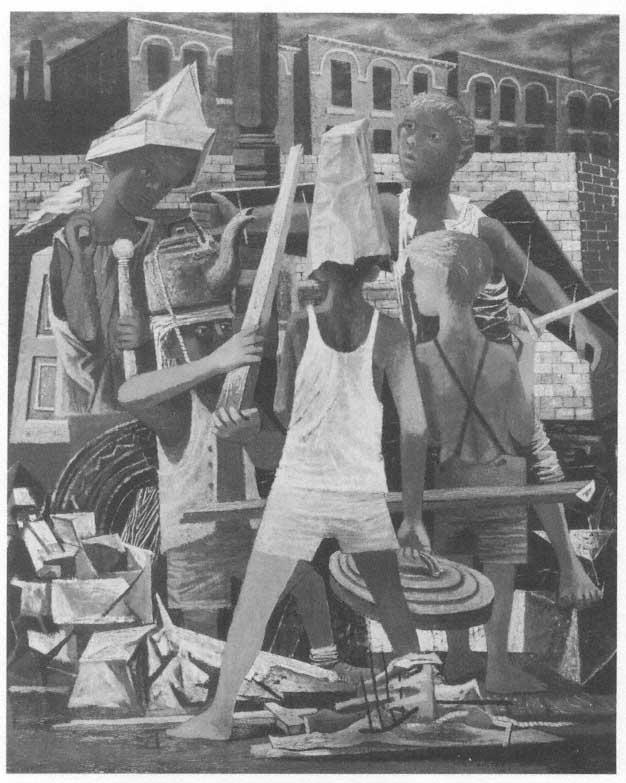

Martial Memory , 1941. Oil on canvas, 39¾ × 32 1/8 in.