I—

Conspirators

Eucalyptus trees and cults. Mecca of beauty queens and retired secretaries. Everyone on wheels. Nathanael West described it in The Day of the Locust with its "Mexican ranch houses, Samoan huts, Mediterranean villas, Egyptian and Japanese temples, Swiss chalets, Tudor cottages" all made of "plaster, lath and paper" that "know no law, not even that of gravity." This mélange brought a wry smile to West, who recognized that "it is hard to laugh at the need for beauty and romance, no matter how tasteless, even horrible, the results of that need are. But it is easy to sigh. Few things are sadder than the truly monstrous."[1]

The truly monstrous found a natural home in Hollywood and spread out over greater Los Angeles. But paradoxes abounded. Along with the freaks and worn-out dreamers described by West was West himself, and scores of other distinguished writers, composers, and painters nesting in the canyons and sometimes enjoying the favors and fortune dispensed by the film industry. Los Angeles was rich with hungry intellectuals who for various reasons settled into Pacific splendor, staring out at the great sea but also looking anxiously eastward from where their moral nourishment came. The Los Angeles bungalows with their trails of bougainvillea harbored more outsiders than most

cities, among them, the restless children of the newly arrived, including Guston, who was born in Montreal during the first stage of his parents' emigration journey and brought to Los Angeles at the age of six by hopeful parents. There, like so many others, the family did not fourish. Nor did the families of Guston's friends of his early adolescence, many of whom shared similar backgrounds: Reuben Kadish, whose father had fled persecution after the Russian Revolution of 1905, first to Chicago where Reuben was born, and then to Los Angeles when he was seven; Jackson Pollock, whose family had wandered in the Southwest for years before settling in Los Angeles when Jackson was in his early teens. Others, similarly foreign to the local mores, gathered into a small, comradely band of explorers. Like most first-generation children, they fled the aroma of their parents' alien cultures, which faded into the background but were never entirely banished. The very fact of their foreignness to the city helped them to look beyond its physical confines.

In the case of Philip Guston, whose precocity was apparent and whose quick intelligence was functioning at a level beyond his age, the years of adolescence were tremendously intense. His natural ambition emerged early. He began drawing seriously at the age of twelve, and his mother presented him on his thirteenth birthday with a full year's correspondence course from the Cleveland School of Cartooning. However, "after the initial excitement of the different crow quill pen points, the Higgins black India ink, and the several ply Strathmore paper," Guston recalls, his interest ebbed. He was quickly bored by the lessons in cross-hatching and gave up after about three lessons, which brought him repeated letters from the school urging him to continue and become a famous cartoonist. But he had already set himself higher goals. By the time he got to Manual Arts High School he was well prepared to plunge into the higher world of the intellect that he sensed to be far away from his immediate surroundings, and to ponder the events that had conditioned his early childhood.

Some of those events were of global significance. The Russian Revolution of 1917 produced ripples that soon reached even the shores of California. America, during Guston's childhood, lived through the 1920s with an unreasonable fear of Bolshevism and had taken to witch-hunting, cross-burning, and flights into otherworldly fantasy. When Guston was fourteen the death sentence was carried out on Sacco and Vanzetti, causing riots in Europe and deeply disturbing many Americans. During the early 1920s, Aimee Semple McPherson held forth in her Angelus Temple with its illuminated rotating cross visible for fifty

miles around and its five thousand seats filled to capacity—a phenomenon Guston went several times to witness. During the decade, newspapers became daily necessities, filling the world with scandal and political propaganda. Syndication helped such tycoons as William Randolph Hearst to centralize and control the news. At the same time, socialists and anarchists inspired by the Revolution took heart and stumped the land with their messages; the IWW (International Workers of the World, known as the Wobblies) flourished with its theme song, "One Big Union," and reached schoolboys through such sympathizers as Jack London. Intellectuals on the East Coast were reading Nietzsche, Spengler, H. G. Wells, Havelock Ellis, Krafft-Ebing, Freud, Chekhov, Strindberg, Dostoyevsky, T. S. Eliot, and, for those especially alert, James Joyce. They were admiring the cartoons of Art Young, with their tinge of Gustave Doré and Käthe Kollwitz, published not only in the New Masses but also in the Saturday Evening Post. On the West Coast, the child Guston was admiring George Harriman, creator of Krazy Kat, and Bud Fisher, creator of Mutt and Jeff.

Manual Arts, like most American high schools, had great faith in teams, cheerleading, athletics of all kinds, and patriotism. But in the classrooms there were a few cultured teachers, and these Guston and Pollock quickly discovered. Pollock had had the advantage of older brothers who took an interest in his education and constantly urged him to discover the way out of childhood and into the arts. Charles Pollock was already studying art in New York and Sande (Sanford) was soon to embark for the Art Students League. Guston met both brothers at the Pollocks' home when he and Jackson would come home after school, eat chili, and carry on long discussions far into the night. Often Guston had to sleep over, because he lived in Venice, much farther from school than the Pollocks.

Their signal experience in high school, by all accounts, was the encounter with a remarkable teacher, Frederick John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky. Alert to many cultural currents, he exposed his hungry charges to the latest art periodicals, Creative Art and The Arts; he showed them slides of European paintings, particularly the Cubists; he encouraged them to read Mencken's American Mercury and the avant-garde journal The Dial. He was also sensitive to the wave of mysticism that had swept the Western world after the First World War, and he took his students to Ojai to attend meetings where the charismatic Jiddu Krishnamurti preached his heterodox theory of life and love and individualism. In the light of the campfire Krishnamurti exhorted his listeners to resist authority, "the antithesis of spiritual-

ity." He said that "when you bind life to beliefs, traditions, to codes of morality, you kill life. In order to keep alive, vital, ever changing, ever growing, as the tree that is ever putting out new leaves, you must give to life the opportunities, the nourishment.… Revolt is essential in order to escape from the narrowness of tradition, from the binding influence of belief, of theories."[2]

Hearing about revolt not only in the soft night of Ojai but also in the avant-garde journals, Pollock and Guston, not surprisingly, undertook some revolutionary activity of their own. Conditions in Manual Arts High School were unsatisfactory for them: all the school's money was going to athletes, and the two boys wanted a creative arts project. They produced a broadside featuring satirical drawings attacking the English department. At dawn they stuck these mimeographed protests in faculty mailboxes and waited with some apprehension for the results. They were not discovered. Emboldened by their initial success, Guston and Pollock produced a second pamphlet, for which Guston did a drawing of a tail-wagging dog titled "Shall the Tail Wag the Dog?" This time they were caught, and both boys were brought before the principal, who promptly expelled them. (Pollock was readmitted later, but Guston never went back.) At the time of their expulsion, Guston and Pollock were Schwankovsky's star pupils. Guston recalls making "enormous drawings, foolish drawings, abstract things influenced by Cubism" while Pollock was doing abstract sculptures. Not far away, in a neighboring high school at about the same time, Reuben Kadish, who was soon to join Guston and Pollock in their rebellion, was also expelled for having led a strike against corporal punishment.

This upheaval in their schoolboy lives occurred in the academic year of 1928–29, just before the Crash, which took place in the America to which their alien parents had come dreaming of miracles. These boys were living in a society that was so truly fantastic that it could not easily be caricatured. The vision George Grosz had had in faraway Germany long before his first visit to Los Angeles in the early 1930s accurately summarized the conditions of the outward lives lived by these teen-aged students. Grosz observed that slogans such as "Service at Its Best" and "Keep Smiling" had become the new forms of soliciting customers. He had heard of a farmer in California named Luther Burbank, who, it was said, could grow plums with no pits. From America had come letters to Grosz's mother offering her membership in a worldwide "mystic" club for only $12.00. "A miraculous country this America, where business, mysticism, religion and technical progress flourished together."[3] He kept track of the teddy bear fads and of

the new sports, such as Diabolo, a kind of string game played to the tune of the new song "Since My Old Man Caught the Latest Craze of D -I -A -B -O -L -O ." This America, and the America that maintained "Red Squads" that invaded private homes, including that of Reuben Kadish, tearing everything apart and destroying books with impunity, was the site of the everyday life of Philip Guston, Jackson Pollock, and the other cultural dissidents flung out of high school.

By 1930 America was slipping into the Depression. Los Angeles, thanks to Hollywood, slipped more slowly than the rest of the country. S. J. Perelman, who had gone out to make capital in the movie industry wrote home: "There is an air of false prosperity out here that makes news of breadlines and starvation unreal."[4] But the young artists were listening intently to voices of rebellion. The climate had changed since the arch and essentially apolitical 1920s, when such magazines as The New Yorker were founded. Now the New Masses, which had been a small radical journal, became a necessary source for intellectuals, and good writers such as John Dos Passos and Edmund Wilson contributed to its pages. While these high-school intellectuals still coveted The Dial, they were now aware of the ardor of the Left. Guston himself had met a poet, Don Brown, who had introduced him to Joyce, Pound, Cummings, the French Surrealists, and little magazines such as transition, but he also kept up with his young companions whose interests had turned to the literature of the Left.

The years between Guston's seventeenth and twenty-third birthdays were patterned with experiences that were to contribute to his formation as an artist. Many of his interests converged. He abandoned the charmed circles of Ouspensky and Krishnamurti, and, as he says, got in with a "bad" crowd of radicals, artists, and poets. Like most late adolescents they cruised around seeking experiences and creating minor scandals. Almost all of them were poor, having to work for a living even while going to school and feeling the pinch of the Depression.

Guston was fortunate enough to win a year's scholarship to a major Los Angeles art school, the Otis Art Institute. He entered with enthusiasm but soon discovered the limitations of Otis's tradition. "There I was, thinking about Michelangelo and Picasso and I had to study anatomy and build clay models of torsos." The revered model for painters at Otis was Frans Hals, whose work could not have been more alien to Guston at the time. In exasperation, Guston one day piled up all the plaster casts he could find in a huge mound and began to draw them when Musa McKim, who eventually became his wife,

happened upon him. Her report of Guston's heap of casts spread quickly, and Reuben Kadish, who met Guston around this time, remembers it with relish. Before long Guston, stimulated by new acquaintances in various circles, abandoned his scholarship to strike out on his own.

With fair frequency the young men and women he was now seeing gathered to read transition The Dial, or Cahiers d'Art; to play Stravinsky records on a hand-cranked machine, and to study the latest theories of the filmmakers Eisenstein and Dovchenko. Jules Langsner, a young poet who was later to become a prominent an critic, brought to the group the reflected light of Bertrand Russell, with whom he was studying, and became Guston's lifelong friend. Leonard Stark, who had studied at Otis with Guston, brought his expertise as a photographer. With him Guston made a short film influenced by the new Russian pictures they had seen at the Film Art Theater, the only house showing vanguard German and Russian films.

By this time Guston's image of the artist was permanently formed. An artist worked assiduously, learned the entire history of his art, experimented, and, above all, aspired to greatness. This romantic aspiration was evident to all who knew Guston during his late adolescence. Tall, slender, with a serious mien, he already carried himself like an artist. His energies were marshaled and he knew his direction. Yet he was not indifferent to an ordinary boy's preoccupations. A school friend recalls him in 1930 as "a fashion plate and choosy about girls." His sartorial elegance was largely the result of his having to go to work and ending up with a job at a furrier. This, however, was no ordinary job, and Guston remembers it vividly:

The inner office of the furrier was lined with books, mostly philosophy and theology. Mr. Aronson, who looked like Disraeli, was an elegant, wealthy man who had lost most of his money in the 1929 stockmarket crash and was now interested in radical literature and new radical movements. But he still lived magnificently, had a limousine, and caused me to acquire better clothes. Since there was no business to speak of, I had lots of time to read, and I would discuss with Mr. Aronson the book I had read during the day. It was as if Mr. Aronson needed somebody to talk to.

This job did not last long and Guston soon found another in a large cleaning plant. He learned to live several parallel lives. During the day he drove a delivery truck or worked at a machine punching num-

Philip Guston in 1929. (Leonard Stark)

Guston in 1930. (Edward Weston)

bers on vests, while at night and on weekends he pursued his education and widened his acquaintance with the mysteries of painting. His working life brought him into contact with growing unrest as the Depression deepened. He witnessed strikes and was duly warned about strikebreakers. He heard of goons drawn from the ranks of the American Legion and the Ku Klux Klan. "While working at the plant we had terrible hours, sometimes fifteen hours a day and no unions. I got involved with a strike and saw some violence." Listening to the union men, Guston learned that Los Angeles was supposed to be clean of unions and that the local powers regarded strikes as foreign importations brought by hated eastern organizers. Later he was to hear the Los Angeles art world voice the same line of reasoning: modern art was an alien mode introduced by unwelcome easterners.

During this period Guston occasionally worked as an extra in movies. He met Fletcher Martin, son of Idaho farmers and migrant workers, who had arrived in Los angeles after a stint in the navy and found work in the film studios, though like Guston, he studied art when he could. Through Martin, whose wife was a screenwriter, Guston was able to penetrate the mysterious world of the movie lots, a world that appealed to his visual imagination, and one that paid better than factory work. He remembers earning a grand fifteen dollars a day plus overtime at 20th-Century Fox, where he also caught a fleeting glimpse of Charlie Chaplin leaning against a luxurious automobile. "I did extra

work on and off for about two years," he recalls. "I stormed the Bastille, participated in the fall of Babylon, and, in She by Ryder Haggard, I played the role of the high priest." His most auspicious stint, however, was during the filming of Trilby, in which John Barrymore starred as Svengali, where, wearing a beret and a goatee, Guston painted a nude for three whole weeks in an atelier scene.

A serious student of film, both as a visual art and as a popular art form, Guston accrued firsthand experience on the lots. In addition, he met many great directors both at Stanley Rose's, Hollywood's only avant-garde bookshop, and at Fletcher Martin's home. The bookshop, which has since become legendary, was to be very important for Philip Guston, who at eighteen had his first one-man show in its gallery, thanks to the efforts of Herman Cherry, another young painter. "Stanley," Fletcher Martin recalls, "was the least bookish person I've ever seen and I often wondered whether he ever read a book. He ran a shop which was a combination cultural center, speakeasy, and bookie joint. Stanley would get whiskey and/or girls for visiting authors and Saroyan made him his exclusive agent to the movie studios. The ambience was wonderful, something like your friendly local pool hall. He liked artists and always had a gallery in the back."[5] Through the shop Guston was able to meet Josef von Sternberg (who, he remembers, owned paintings by Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco, and whom George Grosz had called "Svengali Joe") and Erich von Stroheim; at dinners in Martin's house he met John Huston, Jean Negulesco, and Delmer Daves.

Guston exposed himself on the one hand to the theoretical and highly artistic aspirations underlying the film art and, on the other, to its popular, demotic power. Even then, the crude power of popular art forms impressed him. His keen interest in the comic strip and the animated cartoon was not solely artistic but sprang as well from his need to draw upon the vigor of unrefined expressions. Guston was not alone in this. Some of his older mentors (in periodicals, that is) were also watching closely for signs of native, unsophisticated vitality. When William Carlos Williams teamed up with Nathanael West to publish the little magazine Contact, he welcomed an article by Diego Rivera for the February 1932 issue called "Mickey Mouse and American Art." In it Rivera talked knowledgeably about "perishable" folk art and praised the concision and authenticity of the American animated cartoon.

West, whom Guston met through Fletcher Martin, after some months of collecting material for Contact began to notice a pattern

that worried him greatly. He noted in an editorial that manuscripts had arrived (around 1931) from every corner of the United States and that they all had violence at their core:

In America violence is idiomatic. Read our newspapers.… In America violence is daily…what is melodramatic in European writing is not necessarily so in American writing. For a European writer to make violence real, he has to do a great deal of careful psychology and some sociology. He often needs three hundred pages to motivate one little murder. But not so that American writer. His audience has been prepared and is neither surprised nor shocked if he omits artistic excuses for familiar events.[6]

Susceptible as Guston was at that time, it is not surprising that part of his developing consciousness was directed toward the increasingly obvious malaise in his society. His gravitation to a political viewpoint paralleled his rapid acclimatization as a practicing artist with notably lofty ideals.

After leaving Otis, Guston began to draw incessantly at home. Since Los Angeles had few resources for learning at first hand, he was forced to resort to books for his self-training. In the Los Angeles library he found reproductions of Michelangelo's drawings, Mantegna's prints and paintings, and frescoes of Giotto and Masaccio, and above all, Piero. Guston copied furiously; at one point he did all the heads in Masaccio's Tribute Money. His enthusiasm for Cubism was temporarily suspended while he immersed himself in what he thought of as the great tradition. Not yet eighteen, Guston still felt for the need for guidance, or at least confirmation. Reuben Kadish, who attended Lorser Feitelson's life classes, persuaded Guston to bring his drawings to Feitelson, whose response was gratifying. Although Guston was unable to join the class, Feitelson urged him to feel free to bring his work for criticism whenever he liked. During their first meeting, Guston recalls, Feitelson talked to him about Tintoretto and Raphael and encouraged his pursuit of Michelangelo.

Feitelson had a long professional history behind him. He had begun as an admirer of Cézanne, traveled to Paris in 1919 where he assimilated Cubist theory, and stayed there long enough to witness the beginning of Surrealism. Back in Los Angeles Feitelson assumed the role of a mentor. He was one of the few painters who had ventured to Paris, and one of the few with access to publications from abroad. At the time Guston frequented Feitelson's studio, the older painter had

begun to immerse himself in a study of the old masters, making drawings after Titian, Tintoretto, and Rubens and adopting a classical manner of chiaroscuro modeling. Like many American painters, Feitelson felt cut off from sources and far from the spiritual home of art. He tended to worry a great deal about the role of "dogma" and to rehearse the history of art, in an effort to find the key to his own situation in a decidedly provincial city. After a large one-man exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum in 1929, Feitelson began to formulate increasingly wordy theories to defend his new work. Rejecting Cubism, he turned to what he called classicism. But it was classicism tempered by his experiences in Paris, lightly inflected with Surrealist overtones, and resolutely "modern." He could sustain his new conservative impulse by watching the tenacity of such movements as Valori Plastici in Italy and the Neue Sachlichkeit in Germany.

Despite his tendency to be a pasticheur, Feitelson had the good sense to hold himself ready to receive fresh impulses. In less dogmatic moments he would exclaim: "Ultimately, the function of the painter is to paint!" For Guston, Feitelson "opened up the vistas of the Renaissance masters when I was ready for them." And, perhaps even more important in the long run, was the fact that it was Feitelson who took Guston, Kadish, and a few other favorite students to see the only distinguished collection of modern European art on the West Coast. The privilege of seeing Walter and Louise Arensberg in their Hollywood house, graciously and (for Hollywood) modestly furnished and decked with countless masterworks of the modern period, was not wasted on Feitelson's young friends. Those who later made their way in the art world have spoken of the crucial significance the Arensberg collection had for their artistic formation.

The Arensbergs were not merely millionaires displaying their possessions; they were authentic intellectual aristocrats. Walter Conrad Arensberg was a Shakespeare scholar and an expert on Dante; he wrote poetry and had as early as 1906 translated Mallarmé's "L'AprèsMidi d'un faune." He was a friend to many American poets, among them Alfred Kreymborg and Wallace Stevens, who said, "I don't suppose there is anyone to whom the Armory Show of 1913 meant more."[7] Arensberg had bought several important works from that show, including Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase. When Duchamp arrived in New York in 1915 he found Arensberg's studio on West 67th Street already well endowed with modern drawings, paintings, and primitive sculptures. He and Albert Gleizes began to frequent Arensberg's home, offering their advice and helping Arensberg

to become an authority on modern art. Arensberg in turn became a patron to many artists, above all Duchamp, and he became as passionate about modern art as he had once been about Ezra Pound and Imagist poetry. Long before 1922, when he moved to California and, characteristically, installed himself in a Frank Lloyd Wright house, Arensberg had a museum-quality collection of works by Picasso, Duchamp, Gleizes, Brancusi, and scores of other major painters and sculptors of the modern period.

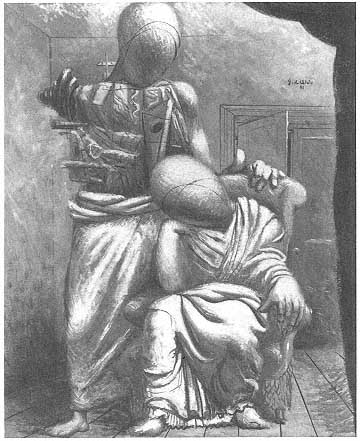

When Guston first entered Arensberg's living room, probably in 1930 at the age of only seventeen, he saw Rousseau's Merry Jesters; Chagall's early masterpiece Half Past Three (also called The Poet) with its fresh, vigorous composition including an upside-down green head, a scarlet tilted table bearing a knife and a round shape like a fruit, and a prominent, out-of-scale cigarette as well as a letter, flowered wallpaper, and a green cat; several sculptures by Brancusi; and numerous works of Duchamp. But it was Guston's first encounter with Giorgio de Chirico that was to have lifelong consequences for him. Guston's recognition was immediate and profound. Although he was drawn to all of de Chirico's work (and is still today a fervent defender, even of the controversial later works), it was not the celebrated Soothsayer's Recompense of 1913 that engraved itself in his memory so much as a later work of around 1925, The Poet and His Muse. While the earlier painting certainly made its impact (de Chirico's wisp of smoke from the vanishing train, the arcaded piazza, the reclining classical statue, and the ubiquitous clock appear in many Guston paintings of the 1940s and the 1970s), it is to the later painting that Guston always refers. The painting shows a room interior with the door ajar, a vestige of a scaffold in the rear, and with two heavy-limbed mannequin figures inhabiting its cramped space. They have featureless heads, the poet sitting listless, dangling a monumental hand, while the muse, with machinelike breast, stands above him. When Guston recalls this painting, what he remembers are the strong, ovoid heads with their modeled contours; the muse crowding the poet's shoulder; and the pronounced floorboards. He associates the weight of these figures with his other enthusiasm of the time, the Roman women of Picasso. He likes to recount the story of the painter Yves Tanguy who while on a bus in Paris passed a small gallery window and was so struck by the sight of a painting that he nearly fell as he jumped off the bus. He had discovered de Chirico.

Guston quickly recognized de Chirico's own sources in the Renaissance, understanding that the metaphysics of the deserted piazzas, for

example, had its origin in the fifteenth century. Years later, he explained his great love for both de Chirico and Piero by saying that he loved them for their muteness. "They don't demand love. They stand and hold you off." This side of Guston's personality—the part of him that admires restraint, formal decorum, and passion that stops just short of excess—was developing rapidly as he worked nights and weekends perfecting his drawing in the classical manner and working out the paintings (including Mother and Child and The Conspirators) that he was to show at the Stanley Rose Gallery. At the same time, he fed his curiosity at other tables as well.

There was, for instance, the circle around Stanton MacDonald Wright, whose fame had been assured when Guillaume Apollinaire wrote in praise of Wright's abstract experiments and dubbed him a Synchromist. The young painters in MacDonald Wright's entourage included Herman Cherry, who had persuaded Stanley Rose to open his small art gallery, and others who had the habit of gathering in Wright's studio on Saturdays where they brewed a large pot of chili and discussed art. After his Paris experiments, Wright, like Feitelson, had turned his attention to Cézanne and to figurative painting. But

Giorgio de Chirico: The Poet and His Muse , c. 1925.

coupled with his classicizing interest in the figure was a parallel interest in Eastern mysticism and, above all, in Eastern visual modes, with which Guston was not in sympathy. Wright regarded invention as primarily an Occidental contribution while he thought of imagination as Oriental, and his own efforts to fuse the two strong currents were reflected in rather bizarre compositions where Chinese dragons consorted with California athletes. Along with Feitelson, Wright stood for modernism in a city dominated by what Guston always refers to as the Eucalyptus School of Painting.

No matter how avidly these young artists explored their surroundings, they were still always in hostile territory. They might absorb messages from eastern art magazines and assume that in New York, at least, there was a climate congenial to their quest, but in their native surroundings they were constantly beset by crude criticism. Poring over Creative Art in 1931 and 1932, they became acquainted with reproductions of work by Max Beckmann, Picasso, Derain, and the French Surrealists. They could read about a young colleague, Peter Blume, who was regarded as a "surreal precisionist"; they could read excerpts from Léger's film theories; and they could see ads for the French periodicals Cahiers d'Art and L'Art Vivant. They could read a mocking article about Los Angeles quoting Louis Bromfield's famous characterization of their hometown as "six suburbs in search of a city," and by 1933 they began to see articles about the Mexican muralists.

In Los Angeles itself, what they read in the press was almost invariably popular cant about the evils and fraudulence of modern art. Editors have long enjoyed reproducing Picasso's works (for instance, one of the Surrealist period, a spiky figure called Bathing Beauty) with scornful commentary. "Do you Call This Art?" a 1931 headline demands, and the lead sentences are: "Many readers seeing the line 'bathing beauty' under this picture will think it is a joke.…Such pictures as this are actually put in so-called 'art exhibitions' and sell for high prices to art 'patrons' with minds as queer as that of the artist." The ubiquitous and implacable Thomas Craven held forth in syndicated columns that reached Los Angeles from New York, scoring practically anything that came from Europe and not hesitating to use such diction as: "Actually, these pictures are no more than visual evidence of the strange practices of freak artists who distort and mutilate the facts of life in order to make fitting patterns for their little nightmares."

Bombardment , 1937–38. Oil on wood, 46 in. diameter.