XII—

The Desert

Guston sprang his secret at the Marlborough Gallery in October of 1970. Shock waves disturbed the peace at Woodstock, but he and Musa had already left for Rome, where he had been offered a studio at the American Academy. But he did not spend much time in it. As before, he wandered to the hill towns, to Orvieto again, to Florence, to Venice, and through the ancient parks and streets of Rome itself. A few drawings and some paintings on paper commemorated his pilgrimage: pink and dusty visions of the stylized trees, their umbrella boles against a pinkish sky. The red stones of Rome everywhere, and dim visions of the hill towns. The memories of detached colossal Roman feet. Fragments.

Then, a trip to Sicily, where they had the great good fortune to see a performance of traditional Sicilian puppet plays—vivid excursions into fantasies of chivalric times, loud with exclamations, and full of the exaggerated combats, the braggadocio of the old tradition. This parallel world, with all its dislocations of scale, its syncopated narratives, its allusions simultaneously to past and present, struck a deep chord in Guston. Months later he excitedly described an evening with an aristocratic collector of classical puppets. The secret shock in the shift of scale seemed to strike him with the greatest force. At moments

Fountain in Rome , 1971. Oil on canvas, 30 x 40 in.

the enormous fist of the puppeteer appeared behind the proscenium throwing the scene into a perspective that delighted Guston. That governing hand, larger than life and paraphrasing the image of the working artist arranging the spectacle, had already appeared in his work. Now it was to become an emphatic symbol in his painter's lexicon.

When the Gustons returned to Woodstock in the summer of 1971, they settled down with a certain finality. The lure of the city was less compelling. In the cottage with its comfortable kitchen always warm in winter, its small rooms lined with books and pictures and enlivened by Musa's collection of smallish objects, life took on a rhythm geared to Guston's sense of urgency. The large studio, whitewashed and orderly, was carefully arranged so that Guston could move from drawing table to painting wall with ease. The telephone was often smothered under pillows. Months went by without excursions and without many visitors. In October 1972, Guston terminated his contract with Marlborough, cutting his ties to the New York art world.

He recalled all his work. "About twenty years of work was rounded up and finally has been trucked up here," he wrote the author in December. "I am on my own and at last 'all together.' I need to build more storage space.… It feels strange to be completely cut off from the city. I feel like burrowing in again—to be a miner and not surface for a while."

He did not surface again for many months. He was painting in long, uninterrupted sieges. Throwing off the last mask. In these new paintings, the absence of the hood is notable. From underneath the disguise emerged another character—a naked eye. This eye—the painter's own—is everywhere: disembodied on a canvas, staring from corners, lodged in great tuberlike heads with no other distinguishing human characteristics. The other attribute, the hand, becomes still more active and, with the eye, dominates the imagery. On one of the many levels attained by the new paintings, the artist reduces his meanings to the clearest statement of his "self": it is nothing other than a fusion of eye and hand working on the things of this world. And also the things of the other world—the world of unease ceaselessly conjured in Guston's imagination.

The paintings from 1971 through 1974 show Guston characteristically gathering up the many themes and techniques that had provided continuity for more than forty years of painting. They are executed in two manners. In the one, great washy spaces steal from one plane to another and seem to dematerialize the objects and figures within them, recalling the brooding works of the Jewish Museum show in mood and technique. These paintings frequently stretch over vast horizontal planes and are, as one of his titles suggests, embodiments of the notion of "desolate." In them, certain formal problems find unique solutions and challenge almost every contemporary convention.

In the other mode, Guston remembers the indispensable "intrusions of the sensible world," as Valéry put it. Here he paints firmly delineated and modeled objects. Solid things. Things lodged in the studio, such as cigarette butts, old flatirons, tin cups. And things that live in his fantasy, such as undefinable but solid objects recalling the geometer's forms in Melancholia —a sphere (wooden ball, balloon?), rectangular forms (wood scraps, canapes?), and the ubiquitous shoes (in these contexts homely objects, more Van Gogh than Goya). The manner of painting recalls both Picasso and Léger in the period after Cubism, a period that had always interested Guston. The manner is emphatic. The purpose is to present the object as firmly as possible, in order to underscore the strangeness, finally, even of everyday things.

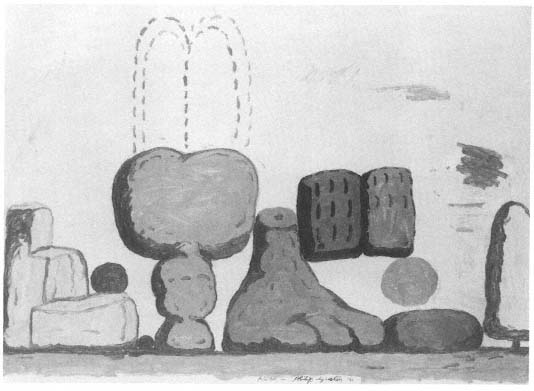

Painter's Forms , 1972. Oil on Masonite, 48 x 60 in.

During this time he read and reread Babel, and enjoyed quoting the Russian writer's remarks to Paustovsky:

What I do is to get hold of some trifle, some little anecdote, a piece of market gossip, and turn it into something I cannot tear myself away from. It's alive, it plays. It's round like a pebble on the seashore.…Its fusion is so strong that even lightning can't split it.[1]

Guston is, like Gogol, concentrating so intensely on the object that it is transformed. And in the transformation resides a great, Panic pleasure. If he arrays his objects, as on Painter's Table (Plate 4), one to

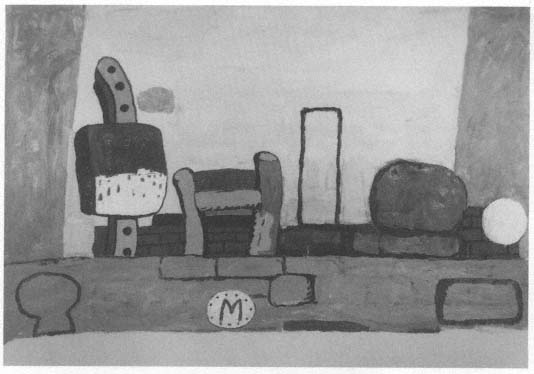

another, side by side, in the rhythms peculiar to him (the familiar bunching together of nearly similar forms and the strange shifts in scale), there is a formal satisfaction that overrides the still-life motif and almost reverts to pure painting. If as in the aptly titled Complications he remembers de Chirico, bracketing mysterious forms in an infinitely ambiguous space, he also remembers his own games of levitation, prosceniums, incongruous objects. The pleasure in a painterly conundrum is not disguised. What is where? The old question elicits delight. His pleasure is pleasure as he had known it described by Kierkegaard:

The essence of pleasure does not lie in the thing enjoyed, but in the accompanying consciousness. If I had a humble spirit in my service, who, when I asked for a glass of water, brought me the world's costliest wines blended in a chalice, I should dismiss him in order to teach him that pleasure consists not in what I enjoy, but in having my own way.[2]

Without any question, the painter whose dialogue had taken into consideration so many problems has taken distinct pleasure during the 1970s in having his own way. Kierkegaard's views, which Guston had

Complications, 1973. Oil on canvas, 53½ x 79½ in.

cited on so many occasions, extend even to that other prominent element in the paintings of the 1970s, the element of farce. From the days when he painted the hoods flinging bricks, to the days when he depicts himself and his attributes (himself coughing up a few essential symbols whose meanings may or may not be simple), the farcical is always in the wings. Entertainment—the horse laugh—is not foreign, as it was surprisingly not foreign to Kierkegaard:

On the other hand, for the cultivated person who at the same time is free and easy enough to entertain himself independently and has enough self-confidence to know, by himself, without seeking the testimony of others, whether he has been entertained or not, the farce will have perhaps a very special significance, for the fact that it will affect his spirit in various ways, now by the spaciousness of the abstraction, now by the introduction of a palpable reality. But of course he will not bring with him a readymade mood and let everything produce its effect in relation to that, but he will have cultivated his spirit to perfection and will keep himself in the state where not one single mood is present, but the possibility of all.[3]

But on the other hand—as there is always the other hand in Guston—high spirits give way to darker thoughts in many of the paintings. The allusion to de Chirico in Complications is one kind of allusion. There is another kind. In those landscapes filled with terribilità, in which vertical legs are terminated by heavy shoes with every nail clearly indicated, recalling the de Chirico towers, recollection is tainted with contemporary horror. Where de Chirico made historical palimpsests of thirteenth-century towers and twentieth-century factory chimneys, Guston isolates another kind of historical memory. And he alters the concept of time. Clocks, which appeared early in his work, possibly in deference to de Chirico, now reappear. Crazy ticking. "It is a real place to me," he wrote in August 1974, "this world I am painting. I feel as if I lived there, its forms defined. All I really need is time and more time to 'reveal'…I pretend I am away (and so I am!) all sorts of tricks to gain the necessary continuity of TIME." The clocks become larger and larger, and the light bulb (occupying the defining space the way Picasso's light bulbs did in the 1930s) hangs more and more precariously, its beaded chain swinging like a metronome.

It was no use pretending that the outside world was outside. It came to Guston, as it often had in the past, through the printed word, and stirred his feelings. Goya, the blackest and most fantastic Goya,

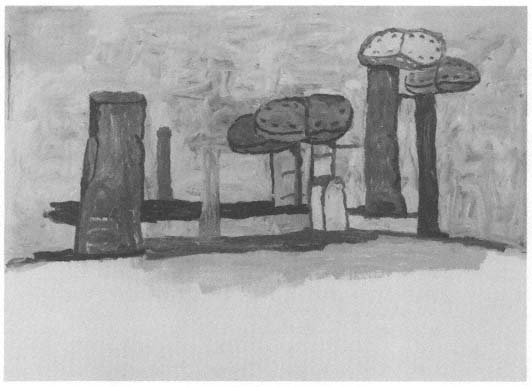

Desolate, 1973. Oil on canvas, 78¼ x 110½ in.

reentered his thoughts. After the coup in Chile he wrote, "Our whole lives (since I can remember) are made up of the most extreme cruelties of holocausts. We are the witnesses of the hell. When I think of the victims it is unbearable. To paint, to write, to teach in the most dedicated sincere way is the most intimate affirmation of creative life we possess in these despairing years."

Blows rain down in the word. When Nadezhda Mandelstam's second volume, Hope Abandoned, was published, Guston wrote of Joseph Brodsky's review:[4]

One paragraph I must quote since it is saturated with what I or I should say we wake up with daily: "Mme. Mandelstam should be believed when she speaks of the moral degradation of mankind and says that this degradation is devoid of national character and is not determined by concrete political processes. To justify existence, I repeat, Russian literature had done more than any other, and if a Russian writer says today that we are all criminals, it pays to listen

carefully. When a Russian refuses consolation, it means that things are bad, it means that there really is no consolation. This is a book about how to live without consolation. Without consolation one can live only on love, memory and culture.…"

I feel such identity with this—I feel this is what my recent paintings are about in a way. Another quote: "The species on the way to extinction, in the long run, is victorious. For its victory is the language created by it, which determines the life of the so-called 'survivor' of the combat." I feel that "language created" which I underline could be "form created".…

In the complex, often labyrinthine processes of Guston's thought, he has never doubted the enduring significance of created form. Throughout his oeuvre, with all its returns to the very beginning, there is a constant and readable striving to discover the immanent structures of painting in itself, insofar as its history reveals it. A poem, he often quotes Valéry as saying, must not vanish into meaning. "Form created" is the ultimate goal, even when it is reached through a juxtaposition of seemingly contrary elements. If there is a tragic undertone in this "survivor's" work, it is, as he himself has said, not separate from a certain formal exhilaration. He has compared himself to the Hasidic dancers who get up to dance in the spirit of despair. But they do dance.

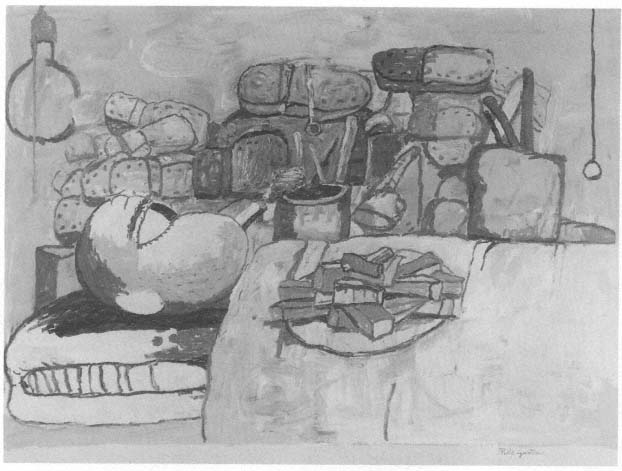

Even in the most disturbing paintings of his recent period, Guston leaps into little ceremonial dances—those flourishes of his brush that can only be seen as tributes to beauty. If he paints himself in Solitary —a great mound of a head, really only an eye, smoking in some godforsaken landscape in which a pile of—what? wood? coffins?—sits somewhere, a hundred miles away from his head, the painting is awash with tender pinks and the pleasure of curious formal relationships. In Painting, Smoking, Eating, a synopsis of Guston's reduction to essentials, there is a twofold, tense situation. Clearly the painter dominates, in the arresting arrangement of forms (piled-up shoes, soles revealed) crowding the upper foreplane, and setting off a lavishly painted plate of French fries. Into this arrangement, so striking in its summary of all Guston's idiosyncratic compositional habits, the unnerving head of the painter thrusts itself. The same grotesquely caricatured head becomes a monument in The Desert flanked by its cat-o'nine-tails and its pyre of boots. The painter, then, is there to disrupt a world of esthetically arranged forms, is, in fact, the unwelcome prophet dedicated to disturbing the status quo.

In a sense, Guston has consciously set out to disturb the status quo,

a task that often takes the form of resistance to his time. The current avant-garde art world he sees as static and conventional. He speaks of the artist who wills to be subversive in society, "but if the subversion is to art itself, that is not enough. It leads to shibboleths."[5] The subversion he practices is a critical subversion, which places him in a position counter to society, a position he feels can lead to "vigorous forms, and paradoxically, to the continuity of art itself." He tempts the world, and he piques the world. He pits anecdote, the quotidian, against the mask, the abstract. Time against timelessness. He courts disdain because, as Octavio Paz has pointed out, a rebel needs to experience one half of his destiny: punishment. Without it, it is hard for him to fulfill the other half: awareness.

Meanwhile he goes on meditating about the nature of an image. "The vice called surrealism," he quotes Louis Aragon, "is the immoderate and passionate use of the drug which is the 'image.'" He feels with equal intensity the pull of images such as "the object painted on

Painting, Smoking, Eating , 1973. Oil on canvas, 77½ x 103½ in.

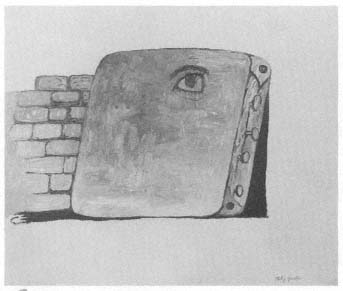

a store window, on a truck, on a placard in a parade, to be seen instantly from a distance," and phantom images, "the enigma of the clear and visible rhythm of the role of forms in space." A moment when one side in this tug of war cedes slightly is seized, and a painting results. Sometimes it is a fixed image, but enigmatic, as in one of the strangest of all his paintings, The Canvas —a canvas more like a stone tablet leaning against a brick wall, with the artist's own eye transfixed. A painting frozen in time and space, yet immoderate and passionate, as Aragon said, and evoking myriad uneasy associations. This painting and quite a few others during the 1970s take on the aspect of an autocritique. The painter critically scrutinizes himself and his caste, sometimes sardonically, as when he dons a hood and paints a selfportrait or shows other hoods viewing a vernissage, and sometimes metaphysically, as in The Canvas. He depicts himself as Picasso did late in his life, as a creature of foolishness and fooling, faute de mieux, but also as one whose destiny is to create (but not will) images. To reveal.

The paintings of 1974 and 1975 are still more revealing. Guston does not abandon his commitment to narrative, but the story he unfolds becomes more intensely metaphorical. He has established a place by means of his small horde of suggestive images: the cave, the room, the lamp and bulb, the clock, the hand, etc. These we encounter from painting to painting and learn to gauge their meanings in each new context. Yet, in these paintings, Guston jumps the boundaries of meaning as Goya had in Los Disparates. His old penchant for ambiguity is brought to its apogee.

As before, he works in two modes. In the one, great accumulations

The Canvas , 1973. Oil on canvas, 67 x 79 in.

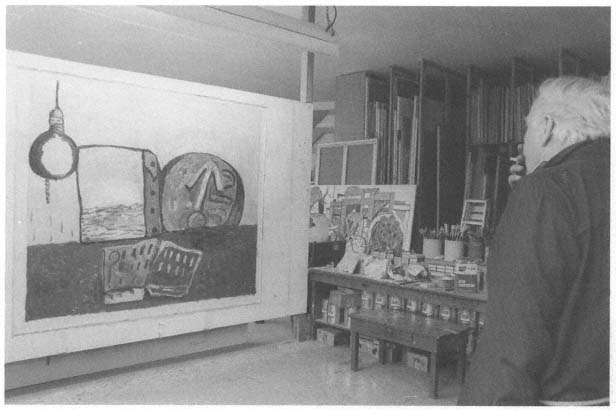

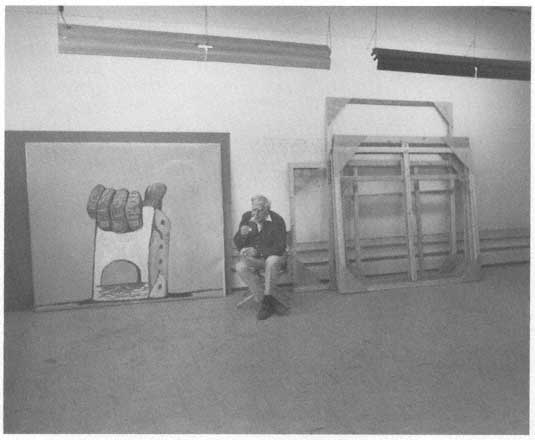

(Denise Hare)

of forms are conjured by the increasingly grotesque head of the painter, his brow deeply furrowed. He remembers. The governing hand of the fateful maker is in monumental scale, and, in a crazy allusion to Piero, is seen flagellating paintings. Between the hand with its rope-knout and the contemplating head of the painter lies a tundra, vast, incommensurable, in which a sinking clock, a bulb, and a sun are arrayed in a complicated spatial arrangement among a stack of painter's stretchers. Below, there is emptiness, measured out by a scale of painter's colors arrayed as though on a palette.

In another painting Guston assumes the hieratic gravity of an Egyptian. He is seen with his creased brow and bloodshot eye in massive profile. One cigarette in the foreplane held in his hand establishes a horizontal and another, protruding from his lips, establishes a second plane. The massive foot on a canvas in the background provides still another clear spatial recession. Here Guston plays with what he once

(Denise Hare)

designated as "the mystery of when you deal with forms in front of forms, as in a deck of playing cards." The overlaps are puzzling and seem to move in and out of focus. By the green shade in the background we know it is Guston's "place." But the formal allusions refuse to declare themselves blatantly. They are, in the most paradoxical way, esthetic—beautiful.

In the other mode, Guston achieves the strange fixity of image that corresponds so profoundly to the ideals of the Surrealists. The conjunction of forms, juxtaposed as wildly as ever Lautréamont could have dreamed, are painted with a conviction that defies their imaginary character. In the moment of dream apprehension, they become more real than real. Tangible and palpable on some level of our psyche, yet clearly fantastic images, these paintings overcome us and create that rare condition Coleridge identified as the suspension of disbelief. The overt symbolism of a huge painting, in which a towering canvas leans incongruously against a clock on a horizon below which is an open book, is reinforced by the suggestion of the endless sea on the canvas, and the hanging electric bulb in the sky. Yet these monuments against infinity tell an inchoate story that will tease the mind everlastingly.

Still more arresting—in fact, haunting—is a frankly metaphysical

painting in Guston's most monumental manner. On a fine linen ground, so fine that it has no grain at all, a thin, evenly applied gray simulates the even inscrutability of the empty mirror. An empty mirror (in itself fantastic since we can only imagine it) sets the psychological tone for the powerful image soaring up from a barely indicated groundline. This image is, like many of Guston's, already a familiar occupant of his "place": it is the tombstonelike portrait of a stretched canvas. On the canvas there is only a hint of the sea and an archway into infinity painted a strange orangelike color, an afterglow color, as irreal as anything Guston has ever conjured. Grasping this monumental object is the familiar hand, its fingers painted firmly, and its thumb jutting up into the mirrored sky on a scale that suggests once again the ancient Roman colossi. This self-portrait (for that hand is unmistakably the artist's own) extends Guston's long soliloquy on the mysterious function of painting.

How he sees himself, and by association the artist, anywhere, anytime, is part of the mystery of his late works, and can only be disentangled from the web of consideration at peril of losing the real meaning of a lifetime's work. "I must quote you something from an essay by Evgeny Zamyatin," he writes in September 1974:

No revolution, no heresy, is comfortable and easy. Because it is a leap, it is a rupture of the smooth evolutionary curve and a rupture is a wound, a pain. But it is a necessary wound: most people suffer from

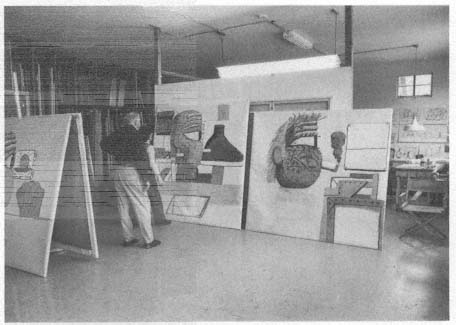

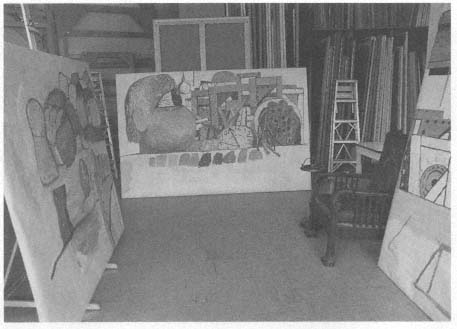

(Denise Hare)

(Denise Hare)

hereditary sleeping sickness, and those who are sick with this ailment (entropy) must not be allowed to sleep or they will go to their last sleep, the sleep of death.

This same sickness is common to artists and writers: they go contentedly to sleep in their favorite artistic form which they have devised, then twice revised. They do not have the strength to wound themselves, to cease to love what has become dear to them. They do not have the strength to come out from their lived-in, laurel-scented rooms, to come out into the open air and start anew. To wound oneself, it is true, is difficult, even dangerous. But to live today as yesterday and yesterday as today is more difficult for the living.

Guston adds: "I jumped out of my skin, as you can imagine, when I read this." Yes, he says, to form and structure. But, he says, and but again…