Introduction

One could write a history of art as a history of temperaments, but it would be as rigid and exclusive as a history of style alone, or of political epochs. Some temperaments, as revealed in works of art, have more or less in common, but art itself shuns commonality: while the scientist may seek the phenomenon that repeats itself, the artist seeks the exception. There are some temperaments that can be defined in terms of the questions they pose. These questions may well have been hovering in the human psyche for centuries, and they recur in the fugue of existence. Such questions are the special province of the arts.

"In the anti-historical position, each artist is…himself."[1] In one of his ruminations, Guston confidently maintains the singularity that marks the artists he has enshrined. But, in another, he challenges the notion of "himself" and expatiates on the relationships that bind the family of artists he admires throughout history. He is, as almost all writers on his work have recognized, a man of dialogue. His work is clearly cyclical. His painting tone alternates, now caressing, now strident. His tastes veer from the sublime equilibrium of certain fifteenth-century masters to the dark reveries of the Romantics. Irreconcilables are the staff of his life.

Guston's reflexive dialecticism is well known to those who have

followed him over the years. They have learned to be comfortable with shifts in conversation from one position to another which, in the long dialogue of his life's work, are finally not inconsistent. Others may wonder at the dualities: the calm Elysian aspiration in the early figurative paintings and the abstractions of the early 1950s juxtaposed with the eruptive abstractions of the early 1960s and the works of the 1970s. They might read a balance sheet of remarks by Guston as proof of his ambivalence. But it would be a false reading. The very basis of his art is the holding in balance of seeming antitheses.

Guston has, as he said of his friend Bradley Walker Tomlin, "a tensile-and at times precarious-balance that covers an anguished sense of alternatives."[2] He can long for experiences "more remote than I know" and dally in the regions of near-mysticism, and he can return purposively to the simplest experiences, curtly replying to his interlocutors when asked about his work, "What do I do? I eat. I drink from a cup."[3] He can exult in the remoteness of Piero della Francesca's oeuvre: "Piero-you don't want to touch it"; he can relish Rembrandt, "all flesh and paint quality." He offers abstract aphorisms such as "doubt is the sharp awareness of the validity of alternatives,"[4] but he also answers his own question "What am I working with?" wryly: "It's only colored dirt."[5] He tells an interviewer in 1965 that he wants to end with something "that will baffle me for some time,"[6] and a few months later tells the same writer, "I am only interested in the weight of the familiar." He makes a public statement that "there is something ridiculous and miserly in the myths we inherit from abstract art-that painting is autonomous, pure and for itself.… But painting is 'impure.' It is the adjustments of impurities which forces painting's continuity."[7] On the other hand, in a taped interview, he states flatly: "I don't believe in alternatives."[8] Yet, alternatives juxtaposed, pondered, worried, turned, and finally neutralized in the finished work, which temporarily dissolves them, are Guston's most familiar companions. They are what he thinks and how he thinks. Like Woyzeck, the creature of Büchner, he can exclaim:

The human being! A lot can happen.-Nice weather, Captain. Such a pretty, solid gray sky. Do you see? One is tempted to drive a log into it and hang oneself thereon, just because of the little hyphen between yes, and yes again-and no. Captain, yes and no? Is the yes to blame for the no, or the no for the yes? Let me think it over.…[9]

Born in 1913, the year of the Armory Show, Guston inherited the

conflicts inherent in modern art. His has been an epoch bedeviled by dialectics. Once Hegelianism had swept the Western world, dialecticism became the habitual mode of thinking. The whole history of modern art could be boxed rather neatly in dialectical sections, and many of its protagonists have consciously adopted the modern method of rhetorical combat. One movement contravened another, one leader gave way to the next, one single purpose deposed another single purpose, and always the anticipated synthesis was held in abeyance. A man of Guston's generation could not avoid the lines of battle, where the rallying cry was always: You must take a position. And it had to be an immediate and definite position before the ground gave way.

But for a man with a sense of the full measure of human experience and an affection for what remains of the past-the works of man's imagination-the position could only be provisional. Guston has consistently maintained an eccentric position-eccentric to the mores of his culture; eccentric to the temporary enthusiasms of the art world; eccentric to, but not alienated from, the given problems of modern art.

Among the numerous dilemmas spawned by the modern tradition are the basic questions: What, after all, is a painting and who is the artist? In the early phases of modern art when Symbolism prevailed, the idea was that a painting, like a poem, was a matter of essences. An image. Something whose value resided in its memorability, its aura, its synthesis of sensations that came together in the mind of the beholder somewhere outside of its actual physical facture. Not a thing, an image.

Such idealism met its dialectical response in realism, which maintained just as positively that a painting was not so much an image or idea as an object. Realists made things, not essences. Whether they were Cubist paintings or abstract paintings, they were to be regarded as concrete entities in a world of things. The clash of the Symbolist and realist views brought a problem peculiar to the twentieth century. In the past it had been taken for granted that analogy was the primary mode of perception in the arts. Recognition sprang from the just analogy, and paint was in the service of memory and sensibility. A few strokes and voilà asparagus-not real asparagus but an analogy for asparagus. However, when painting became autonomous, a thing among other things, the given system of analogies was challenged. If the canvas was a thing in itself, complete, concrete, and not virtual, the dimension of analogy either had to be purged, or adjusted. Some artists simply sidestepped, while others attempted to create a new

kind of analogy, a psychological one that was not immediately apparent. But all were caught in the toils of paradox. The art of painting in the twentieth century has careened wildly between extremes that make the earnest quarrels in the last century between the Ingres and Delacroix camps seem mild by comparison.

At one time or another Guston has met with all the contradictions in the modern tradition. Like most complex artists, he has had several relationships with his time, and those not always exclusive. Yet certain of the inherited problems in his case have found more or less consistent answers, as for instance in the problem of content. Can matter alone carry expressive meaning? He says no. It is not enough to make a mark on a canvas, even if it creates radiant light or rhythmic sequence. Although he experiments constantly, his final answer is no,

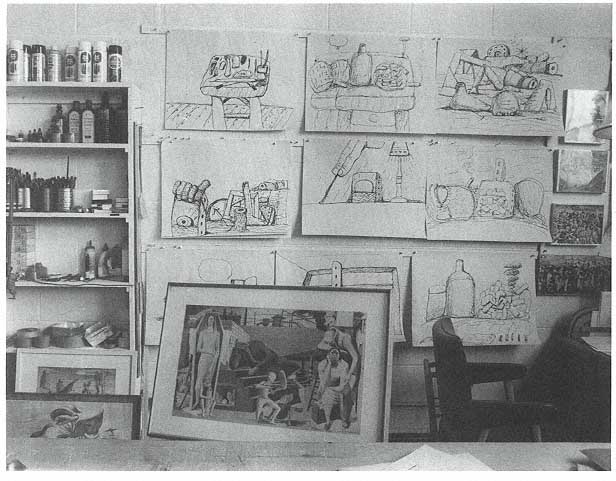

A portion of the design for a mural on housing in 1939 pictured below a group of recent drawings in the

artist's studio, 1975. (Denise Hare)

paint alone is not enough. As for the problem of space as posed in our time: Is the canvas really a two-dimensional surface whose frontal plane must not be violated?-Guston again answers no. The modern shibboleth of planarity is not enough. He has devised means to suggest depth, complicated perspective, close-ups, and he has used tonal modulation to find fresh spatial illusions. He refuses to reject the long history of painting as an art of spatial illusion. The problem of color has also found him firmly rebellious. Although like many other twentieth-century painters Guston did reduce his palette, in compensation he has enriched it with countless intermediate tones with which he has been able to suggest eccentric, even occult relationships within the formal structure of his painting.

Aside from the specific and professional problems of the modern painter, Guston was faced, like all modern artists, with the general problem of modernism itself. With its overweaning demand for contemporaneity, its obliviousness to the past, and its headlong futurity, modernism reduces experience so drastically that artists are always threatened with a spiritual poverty bordering on famine. Guston's stubborn resistance to the modernist's narrow range of experience is central to his existence as an artist. His active opposition has taken many forms, for no source of inspiration has been ruled out. He reads omnivorously. He looks at paintings. He communes with artists in the fifteenth century, and he converses with the painter in the studio down the road. He may find inspiration one day in a poem by an eighteenth-century poet or in a poem created that very morning by a friend. Conversations, dialogues, letters, notes, a reminiscence, a quarrel, a reconciliation-anything may set him off. Everything enters as potential nourishment. While it might be true, as so many critics insist, that much modern art feeds on art, Guston's art must be said to feed on works of the spirit, wherever they may be encountered. Accordingly, a straightforward stylistic account of his life's work would be insufficient. His has been, and remains, a spiritual quest. His constant returns to beginnings-his own and those of others-defy linear analysis. His artistic biography must in some measure be a biography of the spirit. From works alone a great deal can be deduced about a man: his tenderness, his violence; his skill and industry; his loves (of past, of space, of ambiguity, of honesty, etc.); his hate and his selfhate. But just as certainly, his work is derived from his sorties to "life," whether they are readings, encounters, or meditations, and his other-than-working life provides for a more ample interpretation of the work

itself. How Guston's oeuvre has been fed by his life, largely a life of the spirit, is almost as significant as the oeuvre itself, for it is what he brings back from the world that is finally distilled and becomes, for himself and the world, the most significant aspect of his life.

In 1970 Guston exhibited a group of new paintings that were greeted mainly by shocked silence or blatant derision. In an unusually prominent headline, The New York Times broadcast its extreme disapproval by calling Guston a "Mandarin Pretending to Be a Stumblebum." This harsh judgment was upheld by most other reports on the exhibition. Even Guston's longtime defenders seemed uncertain of their own responses and either remained silent or loyally quoted Guston himself on the meaning of the new paintings. (A notable exception was a long, sympathetic review by Harold Rosenberg in The New Yorker.) The asperity these paintings called forth reminded many of the shrill responses made years before to the work of Guston's boyhood friend Jackson Pollock.

Remembering the delicate abstractions of the 1950s, or the dark abstractions of the 1960s, which had led the British critic David Sylvester to call Guston "Abstract Expressionism's odd man out," Guston's critics found themselves at a loss to explain his sudden plunge into a narrative realm of hooligans in hoods, naked electric light bulbs, and smoke-filled rooms. They were unstrung by the stacks of dismembered bodies and odd shoes strewn in a bleak no-man's land, the dread visions offered in a style heavily inflected with caricature, where tender passages only served to underline the irony.

Years before, in the late 1940s, when Guston abandoned the wild allegories that had even won him the approval of Life magazine (the issue of May 26, 1946, warmly appraised his Carnegie Prize-winning Sentimental Moment and reported with satisfaction that the young artist could command as much as $2,500 for a painting) for tense, rigidly composed allegories of violence, his baffled admirers asked one another: How could a man who could paint such beautiful pictures choose to paint such dreadful ones? Then, when these elaborately condensed figurative paintings had finally gained the attention and admiration of serious critics, he swerved toward abstraction, calling down the wrath of those who had seen him as the last bastion of traditional painting. And so, throughout his public painting life, Gus-

ton has known the extremes of smothering approval and acrimonious rejection. Viewers have always responded with alarm, as though Guston's habitual retrieval of ancient themes and his constant reassessments of abiding obsessions were not apparent in every phase of his work.

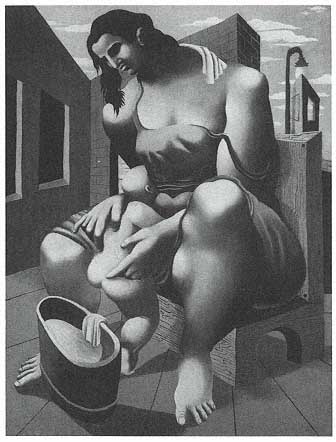

Had his critics in 1970 considered his entire oeuvre, they would have been obliged to recognize that Guston, far from willing to be a maverick, as one newspaper headline had it, was, in fact, resuming preoccupations that had been roused in him in his early youth. This was no posturing mandarin speaking. It was the mature artist, gathering in his resources from the beginning, seeking to express truths of which he had had an intimation while still a boy. Some forty years before, in his first exhibition at the Stanley Rose Gallery in Los Angeles, Guston had exhibited two paintings in which the motifs of the 1970 show were already stated. The seventeen-year-old painter had worked for nearly a year with characteristic ambition to paint a masterpiece. Mother and Child, inspired partly by Max Ernst's satirical Virgin Chastising the Christ Child, partly by Picasso's monumental women of the 1920s, and partly by Guston's copies of Michelangelo's drawings, bore the marks of his sources proudly. The mother's limbs swell mightily; the child is archetypal; a homely chair and a washtub stress Guston's feeling for contemporaneity. Or perhaps the chair and washtub were early evidence of Guston's instinct for plain objects as the firmly weighted constants around which his fantasy could revolve.

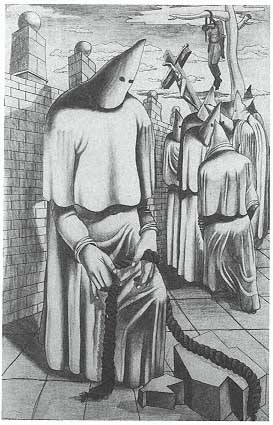

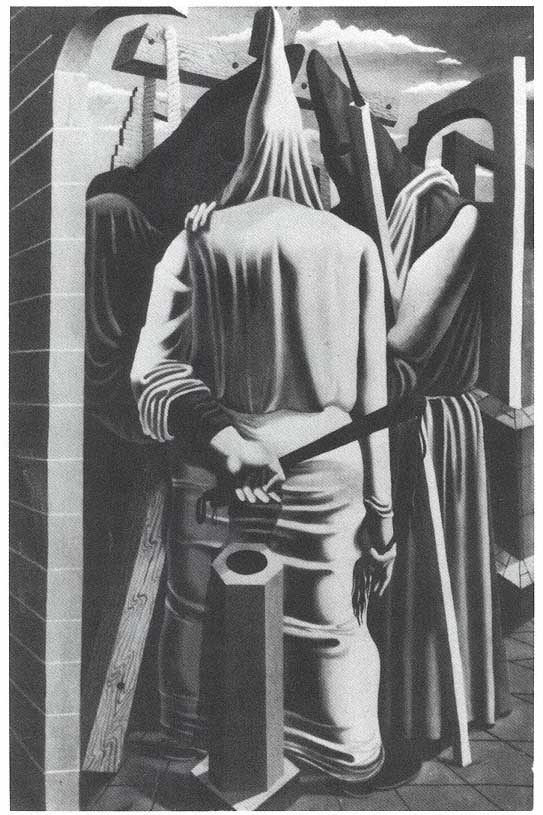

The other painting of 1930 is a more obvious source for his later works; even its title he was to use again in the 1970s-The Conspirators. It is a sharply modeled, carefully composed group of hooded figures who would have been identified immediately by contemporaries as members of the Ku Klux Klan. At the time Guston was working on this painting it was estimated that there were more than 4.5 million members of the Klan in the United States, a great many of them residing right in Los Angeles, where they burned crosses and raised hell all during Guston's childhood and youth. At the same time, Guston had already conceived his enduring love for the painters of Quattrocento Italy, many of whom had painted hooded figures in procession. It is possible that Guston had already seen reproductions of Piero della Francesca's Madonna della Misericordia, in which one of the kneeling figures wears a penitential hood. Like Piero, Giorgio de Chirico has stimulated Guston's imagination from his earliest studies to the present; in The Conspirators the milky blue sky and sharp

contrasts of light and shadow recall de Chirico's haunting metaphysical landscapes.

These two paintings, created before Guston was twenty, can literally be regarded as the first statements of themes that were to be recapitulated throughout his career. These were not only themes in the sense of narrative content but, in a more complex sense, themes that embrace his dialogue with himself, his own past, the past of the human race, and contemporary events. In Guston's life, as in a painting, the background is always related to the foreground. The present is unthinkable without a past. The work of the 1970s is a characteristic Guston mixture of autobiography, myth, and art-the work of a meditative temperament. It springs from the same artistic quest that he recognized in Paul Valéry, who could say, "For my part I have a strange and dangerous habit, in every subject, of wanting to begin at

Drawing for Conspirators , 1930. Pencil on paper,

22½ x 14½ in.

Mother and Child , c. 1930. Oil on canvas, 40 x 30 in.

the beginning (that is, at my own beginning) which entails beginning again, going back over the whole road, just as though many others had not mapped and traveled it.…"[10]

There can be no adequate understanding of Guston's life's work unless we are prepared, as he was and is, to go back over the whole road.

Conspirators , c. 1930. Oil on canvas, 50 x 36 in.