X—

Inside Out

There was always a tendency to caricature in Guston's drawing, which departed freely from mimetic description in order to stress the character of the action in his compositions. Caricature is at its best a characterizing gesture. If the objects staggering to the fore in disguise in the last abstractions were not precisely identifiable in their lineaments, they could be sensed in the character of Guston's line. His characterizations of cups, heads, and even figures, can be read in the massed brushstrokes and identified. As they emerge more and more insistently, these inhabitants of Guston's "other" world partake of the grotesque.

The shift from the lyrical to the grotesque is always potential in Guston's oeuvre and, in this, he belongs to a substantial family in the history of art that knew both impulses (the most obvious being the Spanish painters Velázquez and Goya). The grotesque was within his painting culture, built from the foundations of the early Italian Renaissance, and the word itself, as Wolfgang Kayser tells us, derives from the Italian word grotta, or cave, because the grotesque as a style was discovered during fifteenth-century excavations. Vasari had quoted Vitruvius's De architectura, in which the contemporary of Augustus characterizes and condemns the new barbarian manner:

All these motifs taken from reality are now rejected by an unreasonable fashion. For our contemporary artists decorate the walls with monstrous forms rather than reproducing clear images of the familiar world. Instead of columns they paint fluted stems with oddly shaped leaves and volutes, and instead of pediments arabesques, the same with candelabra and painted educules, on the pediments of which grow dainty flowers unrolling out of roots and topped, without rhyme or reason by figurines. The little stems, finally, support half-figures of human or animal heads. Such things, however, never existed, do not now exist, and shall never come into being.…[1]

Kayser finds that the most influential ornamental grotesques were the ones Raphael applied to the pillars of the Papal loggias, in which "slender vertical lines…are made to support either masks or candelabra or temples, thereby negating the law of statics." The novelty, he says, consists "not in the fact that, in contrast with the abstract ornamental style, Raphael painted objects from the familiar world (for ornamental combinations of stylized flowers, leaves, and animals had long been used by artists like Ghiberti and his followers) but rather in the circumstance that in this world the natural order of things has been subverted."

This "subversion" is at the heart of the esthetic of the grotesque, which the Italians referred to quite naturally as sogni dei pittori. Painters' dreams are very often peopled with objects and creatures that defy the natural order. The transmigrations and transmogrifications that occur in outright artists of the grotesque are always latent in other artists, for metaphor partakes of such distillations. As Dürer said, "If a person wants to create the stuff that dreams are made of, let him freely mix all sorts of creatures." But, in another sense, if a person wants to create stuff that reality is made of, he very often must have recourse to the grotesque with its ominous displacements and its affinity for the absurd.

Guston's interest in the grotesque had appeared early in his life. It embraced the Renaissance metamorphoses so sharply prefigured in Dante, as well as eighteenth- and nineteenth-century visions from the commedia dell'arte, and the Surrealist extensions and eccentric phenomena of the twentieth century. In Guston's earlier work, there were identifiable allusions to eighteenth-century conceptions of the commedia dell'arte, in which, as Diderot pointed out, physical actions and gestures carry the burden of meaning. The figures in Guston's paint-

ings of the 1940s wear the half-masks of Harlequin, Pantalone, and Columbine. They are caught in moments of arrested motion, just as Watteau had caught his Gilles. In Guston's subsequent reprises of the harlequin theme, there are hints of stylized gesture that relate to Venetian commedia dell'arte portrayals, particularly those of the Tiepolos. In the later Venetian paintings the physical actions and exaggerated gestures of the actors are always orchestrated, as in real performances. If Pantalone stumbles. Harlequin glides—no matter how richly diverse the characteristic gestures may be, they are designed to be answering gestures. Meanings are drawn from the specific movements performed by the actors. Such movements, traced for years by a hand that feels the urge to caricature, naturally form themselves even in the rarefied atmosphere of Guston's abstractions. It is always the context—the interrelation of forms in bizarre or conflicting action—that establishes the nature of the grotesque.

During the nineteenth century the grotesque as a style won adherents among the Romantic poets, who saw an adequate mode of portraying the "modern" sensibility by the use of everyday subjects in bizarre contexts. The tragic saltimbanque emerged, with his aspects of absurdity and shades of comic ridiculousness. Much thought was given to the demonic urge that leads to ambiguous laughter, and poets and painters alike produced capriccios that carried the dark side of the grotesque into a superficially lighthearted motif. The extent of their preoccupation with the grotesque can be judged by Baudelaire's constant return to the subject. His attempts to define caricature in "On the Essence of Laughter," and in his writings on Goya and Daumier, range wide and allow for the larger interpretation that has shadowed twentieth-century art. Baudelaire understood the distinctiness of the comic and the grotesque: "From the artistic point of view, the comic is an imitation: the grotesque a creation…laughter caused by the grotesque has something profound, primitive, axiomatic.…" And going still further in his analysis of the "modern" spirit in Goya, he wrote, "I mean a love of the ungraspable, a feeling for violent contrasts, for the blank horrors of nature and for human countenances weirdly animalized by circumstances."[2]

Laughter caused by the grotesque, as he said, has something profound about it, and many artists have understood the world in terms of a finally absurd puppet play, a Punch-and-Judy spectacle in which forces of stupidity and violence work mysteriously. The world as a puppet play is one side of the grotesque vision, and there is a liberal

amount of Punch-and-Judy battering and senseless activity in the dark abstractions Guston produced in the mid-1960s. Even Kafka can easily be seen in the tradition of the German grotesque. The forces that subdue K. in The Castle are never clearly identified, but they exist and are sometimes darkly comic. All the characters in Count West-West's domain keep telling K. he does not seem to understand their language, and yet their language seems to be structured like his own. Unaccountably, it is the surveyor K. who is disturbing a natural order, but that order, from his and our points of view, is so unnatural as to verge on the grotesque. The sinister side emerges not in the homely little scenes in the inn, nor in K.'s visits to various stuffy domiciles, but in the gradual unmanning of K. He who was a proud land surveyor—a man with a place in a logically ordered world—is reduced to the ridiculous position of being the janitor of a country school, and inexorably the "forces" push him into more and more hopelessly blundering acts. Yet, as Baudelaire had noticed, while mediocre caricature is nothing but "an immense gallery of anecdote," the true grotesque contains a mysterious, lasting, eternal element. It is this element that appears in all of Kafka's stories and which had attracted Guston with such force from the start. The "subversion" of Joseph K. and K. and the Country Doctor represents the Faustian quest, which, no matter how much it is disguised in masquerades, slapstick, and absurdity, remains a serious and inescapable matter.

But there are other sources closer to home, and one of them, Nathanael West, Guston had met casually in his youth in Los Angeles and had recognized as a spiritual confrère. In the fall of 1960 Guston had been thinking again about West, who "saw the grotesque mass as it was but preserved his compassion." As a young boy, Guston had already registered the impressions of Los Angeles that West was to epitomize in The Day of the Locust, and he had thrived on the same literary sources (Pound, Joyce, Eliot, and above all Flaubert). He had, through his love for de Chirico, brushed past the precincts of Surrealism, while West had invaded the Surrealist visual arts to draw out his own motifs. The epigraph for his first novel, The Dream Life of Balso Snell, published in 1930, was to have been a quotation from the artist Kurt Schwitters: "Tout ce que l' artiste crache, c'est l'art" (everything the artist spits out is art). And, like Guston, West's first works were partly inspired by his contact with the visions of Max Ernst. West's attraction to Surrealism, like Guston's, was only partial, for his conflict of choices—between the fine estheticism of Flaubert and the rowdy mocking of the Surrealists—was organic and necessary to

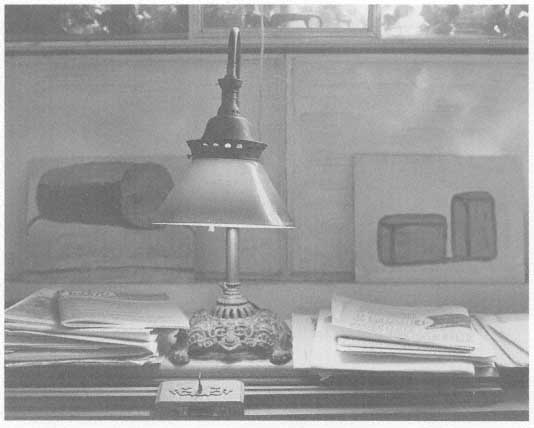

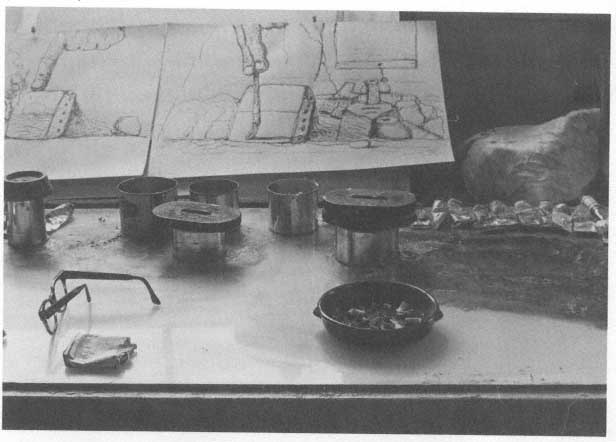

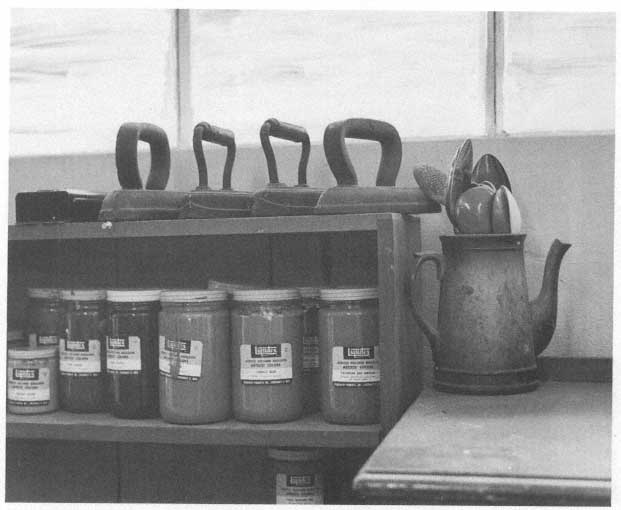

(Denise Hare)

his style. West's early vision of his own work, as reflected in the advertising copy he himself wrote for his first book, showed that he wished to be a part of the movement:

In his use of the violently disassociated, the dehumanized marvellous, the deliberately criminal and imbecilic, he is much like Guillaume Apollinaire, Jarry, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Raymond Roussel and certain of the surrealists.[3]

West's "compassion" was later to dim these influences. In Miss Lonelyhearts, he plays upon Christian themes with a sobriety that belies his Surrealist fancies. His allusions to the visual arts are no longer to Dada impieties, but to such philosophical preoccupations as those found in de Chirico. The dream of his protagonist (who is suffering from the "flu") is familiar: "Later a train rolled into a station where he

was a reclining statue holding a stopped clock, a coach rumbled into the yard of an inn where he was sitting over a guitar, cap in hand, shedding the rain with his hump."

While this was a nightmare, the daydreams in Miss Lonelyhearts also hint at West's search for motives in the history of the visual arts. He must have certainly seen and reflected upon the work of James Ensor, for occasionally there are passages that read like inventories of Ensor's Ostend dream shop:

He could not go on with it and turned again to the imagined desert where Desperate, Broken-hearted and the others were still building his name. They had run out of sea shells and were using faded photographs, soiled fans, timetables, playing cards, broken toys, imitation jewelry—junk that memory had made precious, far more precious than anything the sea might yield.[4]

The Ensor image is even more forcible in West's masterpiece, The Day of the Locust, whose protagonist is a painter. Tod Hackett, as West tells us in the first chapter, seemed with his slow blue eyes and his sloppy grin almost doltish. "Yet, despite his appearance, he was really a very complicated young man with a whole set of personalities, one inside the other like a nest of Chinese boxes. And 'The Burning of Los Angeles,' a picture he was soon to paint, definitely proved his talent." The burning of Los Angeles, which is the leitmotiv of the book, is conceived as a mass scene, in which the grotesque personages described by West surge upon us like the masked figures in Ensor's Christ's Entry into Brussels, each distinct, yet together forming a mob that cannot be contained. "It is hard to laugh at the need for beauty and romance," West reminds us, "no matter how tasteless, even horrible, the results of that need are. But it is easy to sigh. Few things are sadder than the truly monstrous."[5]

The writers who "never really masked their humanity," as Guston once put it, and who yet could register the unflinching cruelty of so much human existence, were the ones necessary to Guston during the 1960s as he sought to "tear off the last mask." He had a natural affinity for writers who could draw a universe down to the last detail and convince us of the most outrageous improbabilities. He was no stranger to Gogol, who could animate objects as unlikely as noses and overcoats, and whose very style was based on the exchange of identities among things and people. In a masterpiece of the essayist's art,

Vladimir Nabokov stresses the importance of context in Gogol's work:

As in the scaling of insects the wonderful color effect may be due not to the pigment of the scales but to their position and refractive power, so Gogol's genius deals not in the intrinsic qualities of computable chemical matter (the "real life" of literary critics) but in the mimetic capacities of the physical phenomena produced by almost intangible particles of re-created life.

That life is filled with both animate and inanimate matter that become hopelessly entangled:

Not only live creatures swarm in that irrational background but numerous objects are made to play a part as important as that of the characters: the hatbox which the Mayor places upon his head instead of his hat when stamping out in official splendor and absent-minded haste to meet a threatening phantom, is a Gogolian symbol of the sham world where hats are heads, hatboxes hats, and braided collars the backbones of men.

(Denise Hare)

Nabokov, in a chapter entitled "The Apotheosis of a Mask," speaks of the story he regards as Gogol's masterpiece, The Overcoat as "a grotesque and grim nightmare making black holes in the dim pattern of life." In discussing Gogol's peculiar mode of slanting the rational plane of life, Nabokov provides brilliant insights into the nature of the grotesque in art:

The absurd was Gogol's favorite muse—but when I say "the absurd" I do not mean the quaint or the comic. The absurd has as many shades and degrees as the tragic has, and moreover, in Gogol's case, it borders on the latter.…

On the lid of the tailor's snuff-box there was "a portrait of a General; I do not know what general because the tailor's thumb had made a hole in the general's face and a square of paper had been gummed over the hole." Thus with the absurdity of Akaky Akakyevkich Bashmachkin. We did not expect that, amid the whirling masks, one mask would turn out to be a real face, or at least the place where that face ought to be. The essence of mankind is irrationally derived from the chaos of fakes which form Gogol's world.

Chiding readers who saw only the pathetic or comic aspects of Gogol's absurd, and who could not see the "real" world Gogol created, Nabokov tells us that "the gaps and black holes in the texture of Gogol's style imply flaws in the texture of life itself. Something is very wrong and all men are mild lunatics engaged in pursuits that seem to them very important while an absurdly logical force keeps them at their futile jobs—this is the real 'message' of the story."

Nabokov's schematized descriptions of Gogol's style reach out to the fourth dimension. "If parallel lines do not meet it is not because meet they cannot, but because they have other things to do. Gogol's art as disclosed in The Overcoat suggests that parallel lines not only may meet, but that they can wriggle and get most extravagantly entangled, just as two pillars reflected in water indulge in the most wobbly contortions if the necessary ripple is there.…"[6] Such a description could easily serve, and superbly so, as a parallel to the images in Guston's work in the late 1960s.

But Gogol was in the background, and Isaac Babel was the writer in the foreground for Guston after the Jewish Museum exhibition. It is easy to understand why Guston, who has said again and again that his

quarrel with modern art is that "it needs too much sympathy," would welcome the laconic voice of Babel, which speaks out, as Babel himself said, with the precision of a bank check or a military communiqué. His stories hit us in the face like seltzer, as Konstantin Paustovsky has said. He quotes Babel as saying that if there is no accurate simile, he would rather let the noun live by itself in its simplicity. "A simile must be as precise as a slide rule and as natural as the smell of dill."[7] But Babel's consuming interest in style, much like Flaubert's, did not mask for him the importance of content. Style and language he thought of as simply high-quality building materials for art. He pondered his art with incessant anxiety, even within his stories. In one of his best images of life in Saint Petersburg, in the story "Guy de Maupassant," he tells of correcting a translation of the French master. "A phrase is born into the world both good and bad at the same time. The secret lies in a slight, an almost invisible twist." He talks to his patroness "of style, of the army of words, of the army in which all kinds of weapons may come into play. No iron can stab the heart with such force as a period put just the right place."[8]

Babel's compassion appears in small doses but with huge after-effects. His narratives are filled with cruel images, and yet they rouse in the reader the agonies of compassion with which Babel struggled in order to tell his tales. The atrocities committed in the Red Cavalry stories are at once savagely graphic and distanced, as though Babel's innate humanity forbade him to indulge in sentimental comments. His descriptions of violence are detached in mode, but passionate in effect. Grotesque truths rattle through his story like machine-gun fire. His compassion cannot be overwhelmed. In one of his lesser stories, "Kolyvushka," he comes close to yielding his secret sentiment. Kolyvushka is a peasant whose farm has just been taken away by the collective. He goes into his field, where his horse "nudges him playfully." Kolyvushka lifts his ax and cleaves the horse's skull. "I didn't mean it," he says, "I didn't mean it, little one," and brokenheartedly adds: "I'm a man."[9] This is as close as Babel ever comes to pathos.

Guston's resurgence of interest in the narrative aspects of his own work encouraged him to forage among artists, such as Babel in literature and Picasso in painting, who had come face to face with the violent currents in human existence. He saw again his affinities with Picasso, who had so often appropriated the caricaturist's line in order to speak of violent human affairs: not only in Guernica and the unforgettable sketches for it, but also in the sharply modeled double-

portraits, the savagely accurate characterizations of animals, and the highlighted images of monstrous visions—fusions of forms that conveyed violence itself not only in the world as Picasso saw it, but in himself as a part of that world. Artists who had availed themselves of wild distortion vied in Guston's imagination with those who had sought to move far from the sordid, demeaning events that offered a vision of man as a victim of dark forces.

Paradoxically—or possibly not so paradoxically—it was during these troubled years after the Jewish Museum exhibition that Guston began to reflect ever more intensely on the most Olympian artist in his pantheon, Piero della Francesca. The great silent mystery of Piero's oeuvre lingered always in his consciousness, even while the sound of blows and violence echoed there. The extremes do touch in Guston's universe, and as time goes by, his vision of Piero becomes more complicated, and even potentially assimilable in his dialectic soul. His straining toward the reconciliation of the beauteous and the monstrous finds its expression in his rereading, year after year, of the "evidence" in Piero's work.

In his twenties Guston, as Stephen Greene remembers, saw in Piero "the mysterious relationships of forms." He read Piero as Piero himself dictated in his treatise on painting: "Painting is nothing else but a demonstration of planes and solids made smaller or greater according to their term." Guston seized upon Piero's felicities of composition and large planar juxtapositions. He saw, as he later reported, that Piero, largely neglected for centuries, was revived thanks to the twentieth century's interest in Cézanne, Picasso, and Cubism. "It must have been the whole interest in painting as structure and the preservation of the picture plane in painting that revived Piero. We saw that all expressive values only come into play on this plane, and that the rhythm of these planes is what's valid." He was in those days concerned with the intentions—the stated intentions—of the Renaissance masters, and understood that "they sought systematically to give the illusion but in such a way that all the forms are readable and rhythmically stated on the plane."

But as he grew more experienced on the plane himself, he began to see in Piero what Nabokov saw in Gogol, those "gaps and black holes in the texture of [his] style." Gradually, the ineffable in Piero became his obsession. His allusions to Piero become increasingly arcane, matching Piero's own invulnerability to verbal description. Guston began to see that in Piero's illusions there was something other, something

(Denise Hare)

that was not, in fact, "readable and rhythmically stated on the plane." During the 1960s he pursued these elusive qualities relentlessly, trying always to define for himself the nature of Piero's peculiar ambiguity. Like a Cabalist, he meditated on the parts, and then on the whole, watching things slip in and out of focus, seizing an insight only to have it dissolve in renewed doubts. He concentrated on the air of "promise" always contained in a Piero, trying to find its cognate in his own esthetic. In 1964, when he had reduced his own palette to qualities of gray, and was all but mired in problems of spatial ambiguity, he spoke to the poet Bill Berkson about Piero's Flagellation of Christ, a reproduction of which was pinned to his kitchen wall: "It continues to provoke in-

finite questions of what it is that is being seen," he said. "You can spend your life puzzling out what the actual intentions of a picture like that are. We are always at the beginning of seeing." Soon after, he published his essay "Piero della Francesca: The Impossibility of Painting" in Art News. He asks the essential question that all painters must ask: Where can everything be located, and in what conditions can everything exist? Speaking of the Baptism of Christ, he says, "We are suspended between the order we see and an apprehension that something may again move. And yet not."[10]

It is this ambiguity of interpretation that preoccupied Guston at this time. He has moved beyond Piero's own treatise to isolate what was peculiar to Piero: "He is so remote from other masters; without their 'completeness' of personality. A different fervor, grave and delicate, moves in the daylight of his pictures. Without our familiar passions, he is like a visitor to the earth, reflecting on distances, gravity and positions of essential forms." Yet, there is more, and more that was akin to the "incompleteness" of Guston's own personality, and this he reveals in his discussion of The Flagellation, in which he finds Piero's thought "diffuse" and that a "play has been set in motion." He notes that the picture has been sliced almost in half, yet both parts act on each other to repel and attract, absorb and enlarge one another. "At times, there seems to be no structure at all. No direction. We can move spatially everywhere, as in life." He moves on from here to his affirmation of doubt, so often expressed in other contexts: "Is this painting a vast precaution to avoid total immobility, a wisdom which can include the partial doubt of the final destiny of its forms? It may be this doubt which moves and locates everything."

These thoughts were further developed a year later in the essay "Faith, Hope, and Impossibility," in which he poses again the questions of "location." He asks "What can be Where? Erasures and destructions, criticisms and judgments of one's acts, even as they force change in oneself, are still preparations merely reflecting the mind's will and movement. There is a burden here, and it is the weight of the familiar."[11]

Guston's thoughts on Piero became intricately interlaced with thoughts about his own work. He speaks in 1966 of the point when something comes to grips with the canvas. "I don't know what it is. You can put paint on the surface most of the time and it just looks like paint. Then there comes a point when it doesn't feel just like paint. That's what I mean about coming to grips—some kind of psychic rhythm." He says that paint on the floor is just inert matter. On the

canvas, it becomes a "peculiar miracle." He wants to be like Piero who, as he had said in his article, worked as though he were opening his eyes for the first time. "I want to paint a world that's never been seen before, for the first time." And he notes that where before he had seen the readable architecture of Piero's paintings, he now sees that they are on the verge of chaos. They are the most peculiar paintings ever painted, more unclear than most modern paintings.

Five years later he was still bemused by Piero. In a lecture given in 1971 at the Studio School, Guston told his audience that "like a needle on a compass I always return to Piero. I'm under the spell of his majesty." He used diction that stressed the majesty of Piero. He spoke of the murals at San Francesco in Arezzo and of his most recent visit there:

Before you see the subject matter, what you see are big soaring verticals and very full circles. Color. Dull reds, milky blues, liver umber, dirty whites. All in a geometry that I never quite saw before. Piero seems cosmic. In all these forms the way in which distances are located, the slowness of spaces moving up and down, at the same time spaces across moving in and out make them seem like planets, Celestial.

Now, in this fully developed meditation, he can speak of the meaning of these murals in which he finds "a feeling of wisdom, an emotion of wisdom." He can extrapolate on his earlier apprehension of the meaning of the picture plane: "By the picture plane I don't mean just surface. This rectangle on which we project an image is a surface upon which you can make a fixation, but that isn't what I mean. It doesn't exist physically. It is totally an imaginary plane which has to be created by illusions."

As he had said in his Piero article, it is not a picture we are seeing but "a generous law." It is on the imaginary plane where the forms of this world momentarily come to pause. "In Piero, you have a sense of pauses, as if all these figures could have an existence beyond these momentary pauses." Since, in his own work, Guston was hovering among such pauses, he was able to say that his only interest in painting is in the metaphysical plane "where conditions exist of infinite continuity." What he now sensed in Piero is the mysterious promise. He returned to the problem in 1973, speaking again of The Flagellation: "The mystery when you deal with forms in front of forms is

paradoxical because something is hidden like a deck of cards. Here, it's the unfolding of these planes on the picture plane so that there is a unified rhythm on the plane as well as coordinated depth in space. The whole question is: when does it pause? The pause in time is a mysterious situation, because it can't be final. It must promise future conditions." And he repeated that the anxiety in painting is essentially based on the question: where can everything be located? In what condition can everything exist? Everything is moving through and up and down and in and out in Piero. Where do you stop? "If there is a settling, it can only be a pause.…"

Undoubtedly Guston's insistence on Piero was heightened by the peculiar circumstances in which he found himself. Always very sensitive to the currents of thought eddying on the local scene and emanating from the art press, he would naturally have been repelled by the hyperbole that flourished during the 1960s, and by the widespread dependence on doctrine. It was a moment when painting was being discussed as if it were a product of a long materialistic process that found its apogee in the lean and schematic works of the "color field" artists. He would undoubtedly have been highly irritated by the new tone of academic scholarship lavished on thin, abstract illustrations of the scholars' own doctrines. The problem with modern painting, he insisted, was not that it was hermetic, but, on the contrary, that it was all too clear. Unlike Piero. And then there was the growing indifference to the past, which Guston noted and, like many other thoughtful intellectuals, knew to be unhealthy. The avant-garde mystique of no-yesterday and no-tomorrow had reached the banal level of much of American life. The avant-garde itself was unconsciously living by the rules of the technocratic society and had lost the dimensions of existence that art had always served to exemplify (the evocation of time, the strange continuity of past and present, the sense of futurity). For Guston, the vulgarity of much art talk was intolerable. Better to return to Piero and the full measure of mystery that painting had always defended. Moreover, Guston had long been a student of de Chirico, whose critique of modern history must have etched itself on his mind. Despite de Chirico's occasional rants against modern art, his cranky and often ridiculous statements about it, his initial observations were legitimately phrased in the visual terms of his art. The Düreresque quality of de Chirico's monuments (references to Melancholia certainly) and the citations from the past that graced his earliest work made him somewhat of a historical commentator. Guston's intimate

familiarity with de Chirico's work—a familiarity that began while he was still in his teens and has remained constant—led him back to de Chirico's own writings which are singularly consonant with his paintings. The Italian artist, during his student years in Germany, had thoroughly assimilated the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, and he alludes again and again to the poetry of Nietzsche in his own writings. Even more striking is the way he synopsized Nietzsche's vision of history in his paintings. In the piling-up of signs spanning many historical epochs he indicates his sympathy with this vision. A classical foot juxtaposed with a modern engineering instrument is evidence enough. Nietzsche's theory that the superior artist must know both the sense of history (and its symbols) and the sense of trans-history, with its dreaming detachment, finds a willing proponent in de Chirico, who admired the German philosopher's aphoristic approach and accepted his judgment that what dignified the ancient Greeks was the fact that they learned, gradually, "to organize the chaos." He frequently echoes Nietzsche's finale to his meditation on the value and disvalue of history: "This is a parable for each one of us: he must organize the chaos in himself by 'thinking himself back' to his true needs." This de Chirico consciously did when he turned his back on his time and pursued the phantom of history in the evocative forms he painted.

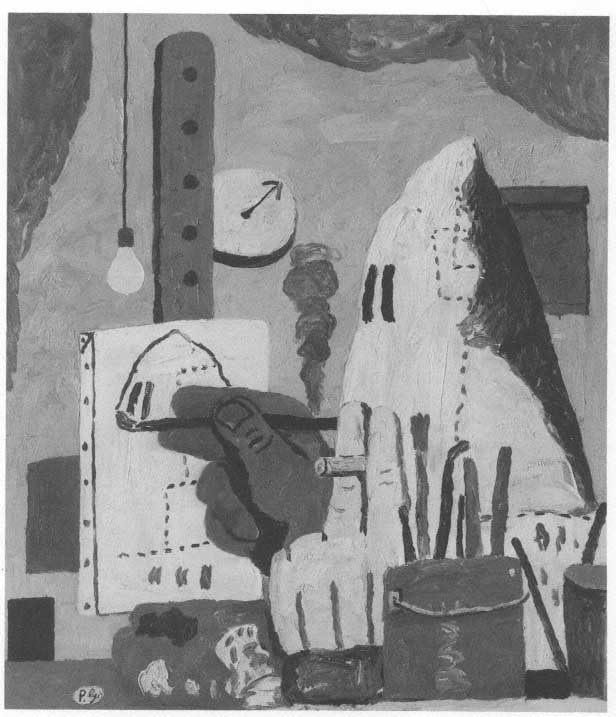

The Studio , 1969. Oil on canvas, 48 x 42 in.