VIII—

Attar

As Guston's drawings piled up in the studio they helped immeasurably in his formulation of a new painting vocabulary. Around 1950 the last echoes of the Porch paintings occurred in Red Painting, in which deep red rectangular shapes align themselves on the picture plane in a largely vertical progression, only to be obscured and at times erased almost completely by deep red impastos laid on in irregular passages, allowing almost no recession. This airless, choked image was the last of Guston's expressions of imprisonment. Air and light and free movement suddenly became imperative, appearing in a painting that Guston regards as one of the central works of his life. During the summer of 1951 he made White Painting, rapidly laying on the tentative shivering forms much as he has done in his drawings. These forms traced a network of interweaving spaces that were all light and flow. The clusters of strokes establishing minute but shimmering contrasts suggested to Guston a rich vein of exploration that released him from his old commitments; they coincided with his great need for direct expression. The analytic requirements of "structure" receded; the structure would speak from within, and without mediation. The sensuous element in painting, which he had always carefully balanced against the

Red Painting , 1950. Oil on canvas, 34 x 62 1/8 in.

structural, became suddenly irresistible. This occurrence is not so unusual in the dialectic history of painting—the pure sensuous experience is always lying in wait for the painter. The weight and magic of paint itself, the mysterious felicity inherent in color, the sheer eurythmic pleasures of texturing all lie on one side of the painter's dialectic. Even the most idealistic or rationalistic painters, such as Mondrian, never completely suppressed the "other" experience. Guston entered this psychological realm with wholehearted enthusiasm. He could truly say, in those days, that he concurred with Valéry (whom he was always reading, and often quoted to others):

I believe there exists a sort of mysticism of the senses, an "Exterior Life" of a depth and intensity at least equalling those which we attribute to the inner darkness and secret illuminations of the ascetics, the Sufis, those who are concentrated on God, all those who know and practice a system of inner withdrawal, creating a whole interior life to which everyday existence can only bring obstacles, interruptions, and occasions for loss or strife—as do also all those images and means of expressing them without which the nothingness. The intrusions of the sensible world are its source of supply.[1]

Guston keenly felt the intrusions of the sensible world. When he was working in Woodstock he was aware of the "forces of natural forms" and observed "sky and earth, the inert and the moving, weights

and gravities, wind through the trees, resistances and flow." He set up these basic experiences in opposition to Cage's void, thereby avoiding what he felt to be the "didactic, conceptual, and programmatic" aspects of Cage's philosophy.

In January 1952 at the Peridot Gallery Guston offered his first oneman exhibition in New York since 1945. The calligraphic lightness of these paintings was quickly perceived by other painters as an innovative mode of great promise. The silvery sparseness and the effect of vibrato were tremendously moving. The show was a significant event and, as a result, Guston joined the Egan Gallery which, at the time, was regarded as an important showplace for artists of the New York School. He was working intensely then, tacking up his canvas and working up close, not stepping back, carried by a furor not unrelated to the exaltation of the mystics mentioned by Valéry. From one canvas to another there was no time to lose and, for a while, Guston found blessed relief in his almost total surrender to intuitive and sensuous preoccupations. Almost total, for Guston's inner inquisitor can never be entirely silenced. Gradually, his old concern for articulate structure began to get the upper hand and, by the time of his 1953 exhibition at Egan, there were paintings with distinctive organization that implied structural reflection. Guston's état d'âme may have been wholly inspired, even intoxicated, by this new voyage into an abstract realm, but his mature, long-trained hand retained the indispensable discipline of pictorial organization.

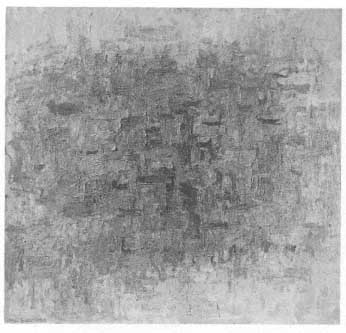

The exhibition in 1953 was widely discussed. It set the small gallery aglow with reverberations of light that led many to talk about Guston's work in terms of "Abstract Impressionism." Guston had enriched his whites with color, chiefly rose-madder and a few ochers, oranges, and apple greens. He had worked out systems of form (grouped verticals contrasted with clusters of horizontals) in which spaces seemed to dilate from an invisible core and were made ambiguous by the almost invisible movements of the linear shapes. The organization of roughly vertical shapes, intersected by horizontals, reminded some serious viewers of Mondrian's plus-and-minus paintings—an association by no means far-fetched given Guston's mood at the time. In the art journals, Guston's new work was regarded with sympathy, although newspaper reports were hostile. A young painter, Paul Brach, wrote that the Egan exhibition was a show of affirmation rather than a denial. He saw "searching and extremely tactile brush work" used to create "an organic centripetal movement—a movement which starts at the silent white periphery of the canvas (where almost any action is a

possibility) then shifts inward to the warm grey mass (with its suggestion of a specific action), then reaches central notations of the strongest color and tension."[2] Another painter, Fairfield Porter, writing in Art News, sees the paintings as descendants of Cézanne's watercolors, but with less air. "Where he weaves the paint again and again the color gets pinkish and translucent, like a bit of sky from a landscape by Sisley or Pissarro. In the middle there are a few bright red or orange strands that center the weight and the color. He seems to have gone beyond Cézanne to Impressionism thereby developing what could be an essential of this style."[3]

The reference to Cézanne is apt, but those to Impressionism and Sisley are somewhat misleading. Until roughly 1954, several critics

White Painting , 1951. Oil on canvas, 57 7/8 x 61 7/8 in.

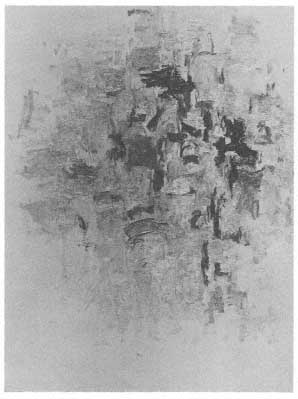

To B.W.T. , 1952. Oil on canvas, 48 x 51 in.

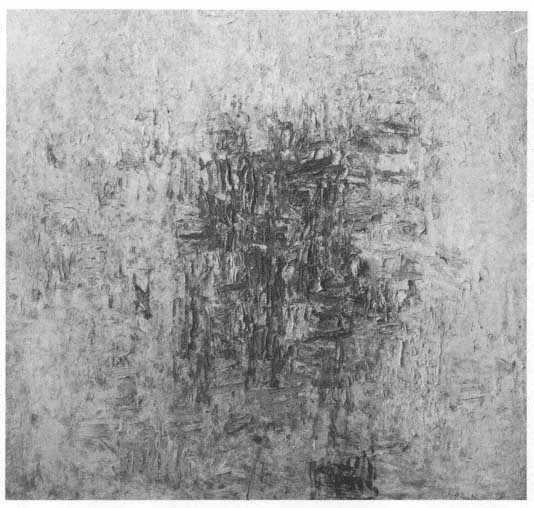

placed Guston more precisely in the radical perspective of the whole Abstract Expressionist movement. Lawrence Alloway noted that these "pink paintings" were works "in which, under the mask of discreet lyricism, he has been most radical, presenting paintings that are the sum of their discrete visible parts. In this structural candor he can be likened to Pollock in his open drip paintings (though not the densely textured ones)."[4] William Seitz noted that "by 1951 the individual brush stroke breaks free to become a primary pictorial element.… It is these pictures that, quite wrongly, were once said to derive from Monet. The illumination and pulsation that radiates through a fog of muted tones is more akin to the mystical light of Rembrandt than to the sunlight of Impressionism."[5] Seitz caught the mood and intention more nearly than did those who persisted in seeing a kind of abstract version of Impressionist esthetics. In the last paintings completed before the Egan show, Guston had developed his "signs"—those ghosts of real solids—in patterns that suggested Cézanne's late works. He worked close to the canvas, grouping, in vibrating units, bundles of verticals or shelves of horizontals. Just as Cézanne had made a schematic system for indicating alterations of light on surfaces, or the angle of perception, so Guston schematized his new vision of a kind of charged atmosphere. But the trembling brushstrokes, which lean to-

Painting No. 6 , 1952. Oil on canvas, 48¼ x 60 in.

gether in uncertain spaces, are totally different in character from the lucid observations of Cézanne. And in these, Guston harks back to the painterly tradition. He retrieves the half-tone and builds up from the putative depths of his image the slow transitions of atmosphere that always mark the Romantic painter's deepest will. Nothing could be more volatile than these delicately differentiated grays, blue-grays, ocher-grays, moving from the depth to the foreground, struggling up to visibility through, as Seitz had said, "a fog of muted tones." They are crowned, as in the painting To B.W.T. (dedicated to Tomlin who, arriving in the studio just as Guston was finishing the painting, had exclaimed, "That's it!"), with floating accents of orange, ocher, or sienna that bring the image forward. The latticelike configuration of stronger tones seems to gather itself into a convex pattern. This circularity of form occurs in other paintings made at around this time, suggesting Guston's desire to draw from the amorphous atmosphere the image of a self-contained universe—to create, as Flaubert had said, something that would be held together by the strength of its

style, "just as the earth, suspended in the void, depends on nothing external for its support." These paintings were to speak through the inner murmuring of near-form, of entities nearing completion but never quite distinct.

"Look at any inspired painting," Guston told a Time reporter in 1952. "It's like a gong sounding; it puts you in a state of reverberation."[6] After the Egan show, the gong sounded close to the ear, and the sharp address can be felt in the way Guston gathered together his forms and began to mass them in emphatic patterns. He was now fully immersed in the absorbing contest with chaos. Abstraction was an intoxicating experience. Like a glider pilot, he could not resist the silences and unknown spaces he had never known before. The rules that had once contained his imagery had fallen away. Now, everything was pitched to successive acts of discovery, and the process itself was the voyage. The brush was quick to transmit the tides of unnamed emotion, but the search, as always, was for the name, the particular form. The emphasis on process that Guston shared with his friend Feldman was described by the latter in an anecdote:

Some years ago, Guston and I made plans to have dinner together. I was to meet him at his studio. When I arrived he was painting and reluctant to leave off. "I'll take a nap," I told him. "Wake me up when you are ready."

I opened my eyes after an hour or so. He was still painting, standing almost on top of the canvas, lost in it, too close really to see it, his only reality the innate feel of the material he was using. As I awoke he made a stroke on the canvas, then turned to me, confused, almost laughing because he was confused, and said with a certain humorous helplessness, "Where is it?"[7]

Feldman, who himself was ineffably attracted to absolutes, shared with Guston in those long conversations in the studio the kinds of speculations that were coursing through Guston's imagination. When years later he sums up their long relationship, he speaks unabashedly of abstract experience, stressing it by his use of capital letters:

The sense of unease we feel when we look at a Guston painting is that we have no idea that we must now make a leap into this Abstract emotion; we look for the painting in what we think is its reality—on the canvas. Yet the penetrating thought, the unbearable creative pres-

sure inherent in the Abstract Experience reveals itself constantly as a unified emotion.…[8]

Guston's own thoughts, as he expressed them in the late 1950s, traveled along uncharted paths, stumbling, groping, trying to seize the essence of his adventure without losing its spontaneity. In 1958 he wrote for the artists' magazine It Is that "only our surprise that the unforeseen was fated, allows the arbitrary to disappear. The delights and anguish of the paradoxes on this imagined plane resist the threat of painting's reducibility."[9] He courted these delights and anguishes, he awaited their appearance with longing; and he knew that in them there came a kind of momentary resolution that could be called freedom. As he wrote in the Museum of Modern Art's catalogue for 12 Americans in 1956, "Even as one travels in painting towards a state of 'un-freedom' where only certain things can happen, unaccountably the unknown and free must appear."

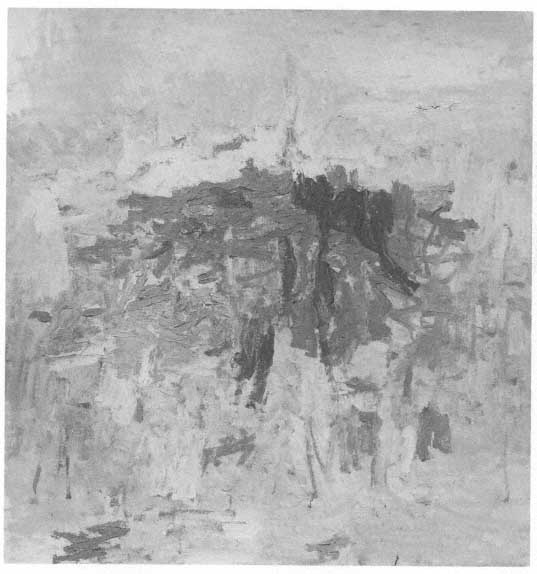

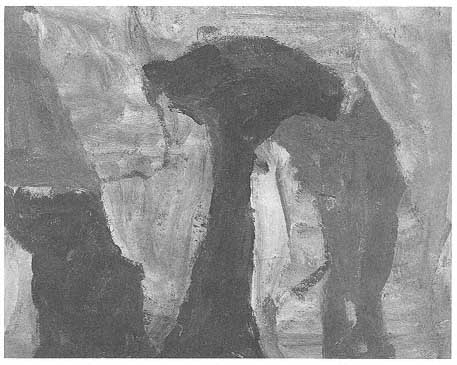

Late in 1953 Guston's statement of paradox—the sighting of boundaries between form and nonform became more emphatic. Working from painting to painting, he produced a readable vocabulary of his dialectic in which the trembling ambiguities of the atmosphere were dominated by increasingly dense forms. The transition begins with Attar, where the strokes are laid on thickly, forming moving units within the pinkish haze and moving upward to what could almost be an horizon. Shortly afterward he painted Zone, where a thicket of rose-madder strokes defined a central form, coalescing to make a complex web on the surface through which glints of a vague and slipping space can be read. The intensity with which Guston brushed on his short verticals and horizontals is heightened in Painting, 1954, where movement and countermovement in a cross-hatch sequence mobilize the massed forms, which seem to move diagonally upward and inward. The increasing use of impasto in these paintings of 1954 indicated Guston's growing need to work with masses to heighten his painterly approach. By 1955 he had evolved a distinctive manner of suggesting vital forms within the still-amorphous atmosphere.

The paintings of 1955 and 1956 move clearly forward toward articulate form. The hesitant, trailing calligraphic notes are reserved for the edges of his paintings, while the centers are orchestrated with increasingly dense masses of strokes. Certain, almost reflexive, movements of the brush appear from painting to painting—a twist to form a rosette, a thrust to build an arch, a series of strokes to plait the thick, scored

strokes, a commalike line to glide out into the infinite of the roseate atmosphere. Convergence becomes more important. In Beggar's Joys (page 112), the scribbles converge in an off-center totality that, by its internal interplay, suggests that it partakes of some of the uncertainty of its environment but has finally defined itself as a mass nonetheless. In The Room, very broad red strokes palpitate heavily while a new value is introduced: the rose underpainting is now partly obscured by broad sweeps of charcoal gray. Dense and unavoidably disturbing, these dark shapes are built into a firm network which, like the shoe in his early work, presses up against the picture plane. The whole central form, with glimpses of air behind its massed strokes, rides firmly in the glowing space; a hint of its potential for separating again is offered in a few echoes of gray and red, floating in different planes in the surround.

Zone , 1953-54. Oil on canvas, 46 x 48 in. (Color plate II)

The Room , 1954-55. Oil on canvas, 71 7/8 x 60 in.

Guston's intention of creating a complex organism of coalescing units to partake of the atmosphere and rise to a climax is best seen in For M, where the charcoal flourishes are very dense, emphasized by cold, whitish surroundings. A single orange accent locates this image in a place wholly resident in reveries—a place infinitely extensive and in which unexpected events can occur. The cool light here, and the suggestion of emotional shadows in the grays, herald the change of Guston's mood. From soft Venetian stage lighting he had derived a genial light that marked his early abstractions as purely lyrical. As he moved into denser color and more complex textures, the light becomes increasingly abstract and arbitrarily emphasizes an awareness of conflict.

This sense of conflict in Guston's work emerges fully in the next two or three years. A painting such as Voyage is not as gracious even in emotional tone. The dense balls of rose, ocher, and orange are massed into an almost impermeable sphere, where nests and pockets are unaccountably congealed to form a convex surface related to the earlier

To B.W.T. As if to make their incongruous union more emphatic, Guston leaves the four edges of the canvas white and only lightly scores the surrounding spaces with neutrals, terra-cottas, and washes of blue. Fibrous lines waver uncertainly in this atmosphere, as though they had broken away from their interlocking matrix in the center. The whole throbbing surface can be read in several sequences (for instance, there is a group of forms that seem like stepping stones to infinity, reading from bottom right to upper left), and yet the impression is finally one of mass displacing the encroaching space. The same is true of Dial, where even the background neutrals have thickened

For M , 1955. Oil on canvas, 76 3/8 x 7272¼ in.

Voyage , 1956. Oil on canvas, 71 7/8 x 76 1/8 in.

and in which arbitrary squared blues suggest a sky that rightly belongs within other vistas of a surreal universe where associations are made to be disrupted. The move from density and volume to pure ether is not simple, and it is certainly not direct.

Guston was puzzling again and questioning. He questioned largely on the canvas, where, painting by painting, suggestive shapes began to reappear. A crutch here, the memory of a wing, or a root, or the oval of a head emerged as he painted. He was forced, almost in spite of himself, to reconsider his assumptions. The title of a 1956-57 painting, Fable, indicates the drift of his thoughts. The evocation of atmosphere was no longer his primary need. Now he works again to suggest drama, with its cast of characters and its "parallel" potency. Strong orange and green accents appear, as well as shapes that lie on the threshold of meaning. The blue is a blue of full daylight, unal-

tered. These lusty scrawls show Guston's confidence that the abstract forms springing from his imagination would be significant.

He had been turning over in his mind the problem of the "loss of the object" in modern painting, and he needed to reintroduce not objects themselves, but the sense of objectness. Diffuseness—an abstract quality—had been the subject of almost two years' work. Now, corporeality was to take its place. Not totally, of course, since it could be expressed only through the existence of its opposite, amorphousness. Small details, interspersed at various levels in the imaginary space he created, served to make the contrast acute. Guston was, for all his enthusiasm and spontaneity, always very attentive to detail. Wholeness of mood was his final goal. If we remember how moved he had been in St. Louis when he first heard the late Beethoven quartets, it is not difficult to find a truth in Morton Feldman's assessment of the particular nature of Guston's abstraction at the time: "In Beethoven," he wrote, "we don't know where the passage begins, and where it

Fable I , 1956-57. Oil on canvas, 64 7/8 x 76 in.

end; we don't know we are in a passage. His motifs are often so brief, of such short duration that they disappear almost immediatelyl into the larger idea/ The overall experience of the whole compositionbecomes the passage."10

The "overall experience" was to remain Guaton's pronounced goal during the next few years, but, as in the late Beethoven, it was to be fraught with hints of agon/ Brief intrusions of extreme anxiety can be increasingly sensed. Agitation disrupts, darkness erupts. There are works still in a light key or a lyrical, melancholy mood, but there are others in which the reverberations are staccato, sometimes even harsh.

The restlessness that overtllk Guston again in 1957 is evident in

Beggar's Joys , 1954-55. Oil on canvas, 71 7/8 x 68 1/8 in.

Willem de Kooning , 1955. Ink on paper,

10½ x 8½ in.

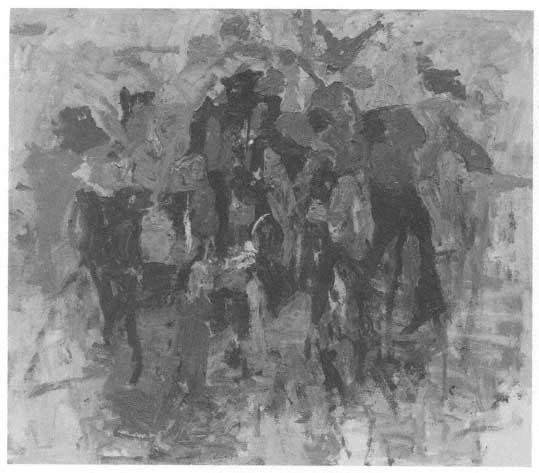

Painter's City (Plate 2), where there is a profusion of interrupted solids with channels leading out of the centered morass. Here turbid massed forms announce a direction he was soon to pursue almost exclusively. But before he became totally absorbed, he painted The Clock, with a tremendous vibrato resounding in the charged atmosphere, and Natives' Return, with gay, bright blue accents, and Passage, its surface awash with long, loping strokes that seem laden with moisture. Then in 1958, in To Fellini, he remembers Painter's City again. To Fellini (he chose the title after one of his mind-clearing expeditions to the movies) is "packed," as he once said Beckmann's paintings were. The image does not huddle in a central site, but spreads aggressively from corner to corner, its darkish passages moving restlessly in every direction. Small details lead the eye into ambushes and dead ends, as large forces spread ominously. Lavish, free brushstrokes escape from the pack, only to be scraped down to thin memories by the excited painter. This is a mazelike mass of directions in which something of the suffocating anxiety of the late 1940s begins to reappear. Painter's City, which existed in a middle-ground, where

paths of escape were clearly marked, is here transformed into a place where agitated forms cannot discharge their energy except within their tenuous constellation, and in which they struggle forward, living in a foreground that conceals unnamed experiences beneath.

There is a sense of crisis in Guston's works that follow this period. Crisis in its basic etymology implies separation and carries with it an implication of things straining away from each other. Around 1956 Guston's outward life as a painter improved. In the fall of 1955 he had joined, along with other major painters in New York—Franz Kline de Kooning, Rothko, Pollock, and later Motherwell—the Sidney Janis Gallery, where he was to show regularly until 1961. His paintings were bought. He had a good studio on 18th Street. Yet his inner life was more turbulent than ever. The far reaches of abstraction into which he had hurled all his emotional energies were beginning to seem too rarefied; the ether was too thin. But the sense of amplitude that his increasingly wild inventions provided filled him with exhilaration. The very matter of paint itself took on qualities he found irre-

Franz Kline , 1955. Ink on paper, 10½ x 8½ in.

To Fellini , 1958. Oil on canvas, 69 x 74 in.

sistible. But nagging at the center of his imagination was the still unformulated anxiety that as a painter he had somehow transgressed. He began to muse about angelism and the whole history of Romantic art. Sometimes he would speak of the classical myths in which feats of transformation were performed, as when Galatea turned her crushed lover into a flowing river. "There is an ancient taboo against an artist's trying to make a living thing," he said, adding that the artist is some-

thing of a demigod, perpetually condemned. "I feel I have made a Golem." The old injunctions against such Promethean activities could not be easily disposed of. Guston looked again at the works of Expressionist painters. He thought about Chaim Soutine, who "was trying to wrest life from his images, to make living things," and felt a deep sympathy with him. But also resistance. It became increasingly clear that the choices Guston had to make lay somewhere in the no-man's land between two kinds of painting he discerned in history, that based on pain and that based on beauty and pleasure. Poussin, he said, didn't give a damn about subjects. Between a Rembrandt and a Poussin lay

Painter I , 1959. Oil on canvas, 65 x 69 in.

Painter II , 1959–60. Oil on canvas, 49 x 47 in.

conflict and the path of his own crisis. On the one hand, as he exclaimed in 1958, "corporeality is what art seeks" and, on the other, he saw forms in a perpetual state of metamorphosis, dissolving constantly in their peregrinations.

The mounting crisis in Guston's attitudes toward his work was announced in the work itself before he was even aware of it. At the same time that he was wrestling with the "packed" and hectic large-scale paintings, he was making a group of small oils and gouaches in which a very few forms of highly suggestive character are brought up very close to the picture plane. Squarish black shapes formed by closely adhering strokes loom up and occupy a space that is dense, corporeal, and no longer suggestive of infinity. The curious shapes that had once come forth from his reed pen in a whole lexicon of small signs reappear greatly magnified and begin to assume a corporeality and "thingness" that shifts the focus of Guston's work. A small, simple gouache such as Actor startles the eye with its curious central mushrooming volume, propped up incongruously by another leglike form. Hints of the later satiric impulse recur regularly in 1958 and 1959, particularly in the small works.

Guston's shift in emphasis is seen even in the titles, which began to focus on the protagonist. His old question, "if this be not I," is now

Actor , 1958. Gouache on paper, 22 5/8 x 28 5/8 in.

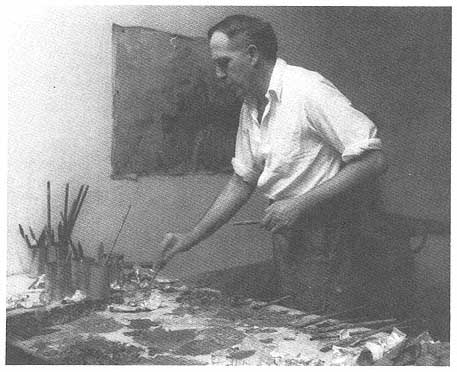

Guston in his loft on 18th Street, New York City, 1957. (Arthur Swoger)

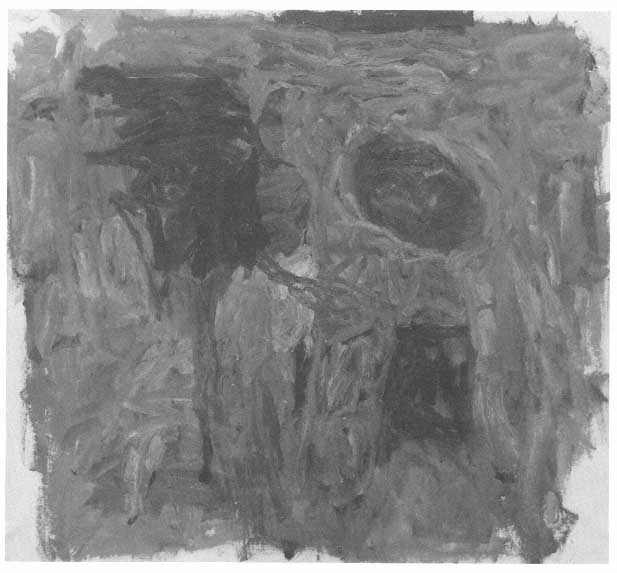

posed in frankly subjective terms, and the "actor" or the "poet" or the "painter" is the innermost mystery that the quickness of his brush hopes to reveal. In Poet, his brush traces the nervous rhythms of an artist's existence and conjures strange shapes that collide, depart, and tear away from a ground no longer gently ethereal but turbidly intermingled with the chaotic forms themselves. The precarious balances suggest not an association with the movement of a poet's imagination but a homologue of the imagination itself. A Golem perhaps. An acute feeling of separation seeps into the painting, which is held together by the most tenuous of washy strokes, and the most hesitant tonal relations. Precariousness is still more evident in Painter I of 1959. Not even the black central forms exist in a state of equilibrium; they teeter on their axes and are curiously hedged by neighboring shapes that cleave to their edges like barnacles. Except for a glimpse or two of bare canvas, a marshy tangle of long, dirtied strokes, the "events" in this portrayal of an alienated artist are inchoate. Struggle and disquietude prevail.

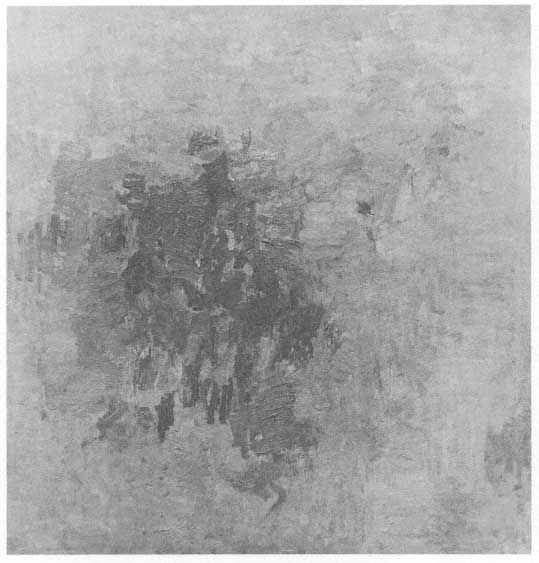

Alchemist , 1960. Oil on canvas, 61 x 67 in.