VI—

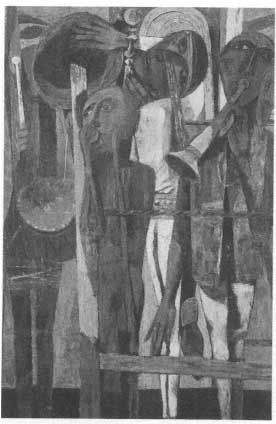

Tormentors

The majesty of If This Be Not I was to impress and influence many people during the next few years. A short while before his first oneman show in New York City in 1945, at the Midtown Galleries, Guston signed his name to the painting and consciously closed a period in his painting life. The exhibition, which had If This Be Not I as its centerpiece, began a public life that Guston needed but found disturbing at the same time. The responses to his New York exhibition were without exception enthusiastic. Yet Guston understood that his viewers responded more to the unaggressive, softly romantic themes than they did to his deeper purposes. He felt compelled to tell an interviewer that he was preoccupied with "ambiguousness" and "metaphor," and that for him, "space with its whole scale of near and far must become as charged with meaning, as inevitable to the composition as a whole as the figures themselves."[1] When, shortly afterward, Guston's Sentimental Moment won the coveted first prize at the Carnegie Institute's annual (not an international that year but an American event, no doubt because of the war), he was uncomfortable. The painting, described by Rosamond Frost as "an utterly frontal study of a woman who fills virtually the entire picture surface," in which "light

shifts delicately over the surface, caresses and models form," was found by another critic to have "a repose and dignity reminiscent of the old masters."[2] Guston himself dismissed it as being "too literal" but not until several months later, when he had embarked on a new course and his process of "dismantling" was fully underway. If This Be Not I was the end of a distinctive chapter in his oeuvre.

Guston's sense of having completed a phase in his artistic life was profound enough to fill him with uneasiness. When he was invited to teach at Washington University in St. Louis in the fall of 1945, he accepted with some misgivings. Teaching had not only undermined his sense of exclusive devotion to his art but had exhausted him. He was at a point in his work where the slightest distraction could throw him into a state of anxiety. When he left Iowa City, he told several students that he would leave much behind him. He was already mentally preparing for a struggle with himself that would end, after two academic years in St. Louis, in what Guston has at various times called a kind of breakdown.

Whatever his inner turmoil, his students did not suffer by it. Walter Barker, a former student, writing in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on February 13, 1966, was to say that his students "remember Guston as a fluent, dynamic teacher who loved his subject. His knowledge of Renaissance drawing, method, and structure was prodigious. Some of his best classes were conducted in a bar on Oakland Avenue next to the Hi-Point Theatre, or the curb outside when it closed, and sometimes on rapid walks through out-of-the-way alleys, and railroad underpasses in west-end St. Louis with long-legged Guston striding ahead of a winded and bedraggled class." These students learned firsthand what a true flaneur could be, for, restless as always, Guston was particularly nervous during this period and spent many hours seeking relief from his gathering mental storm. It was a likely place, anyway. St. Louis was a real city. It had an exceptional museum, then directed by Perry Rathbone, who had been one of the first to recognize Guston's work and to acquire it for the collection. St. Louis had wealth and grace and a group of sophisticated art collectors. It had a symphony orchestra, directed by Vladimir Golschmann, who himself had an exemplary collection of paintings, including several excellent Picassos.

On the other hand, the city had a true proletarian quarter and a lively popular culture. In St. Louis's nightclubs and modest bars, the best jazz and blues from the South were heard, performed by venerable

black musicians of the high epoch. There were a thriving red-light district, a black ghetto, a white ghetto, and behind it all the romance of the old days of lowdown blues—an echo of that St.woman with all her diamond rings. Once again in the heart of a true city, Guston remembered his first city, Los Angeles, where he himself had lived in a poor neighborhood. In St. Louis, far from the calm vistas of cornfields in Iowa, he began to do some sketching in the slums. For his forays in the jazz quarter, he had an excellent guide in William Inge, a Kansas-born writer of Guston's age who was drama editor for the St. Louis Star-Times and who edited the culture page until 1946 when he joined the English department of the university. Inge, later to become famous as a playwright, had long specialized in jazz and took Guston to little bars where they would eat spareribs and talk blues. Perhaps they talked about Inge's own work, which paralleled Guston's Iowa period in its description of small towns, with their "mysterious quiet that precedes a Kansas cyclone," as Inge put it.

It was also in St. Louis that classical music suddenly moved into Guston's emotional life. Through the physicist Martin Kamin, Guston was invited to chamber music evenings played by members of the St. Louis Symphony. Of all the experiences with music through the auspices of his friend, Guston remembers most (what certainly was apposite to his troubled mood) his first exposure to the late Beethoven quartets and quintets. And, of the Picassos in Golschmann's collection, he remembers the double heads, those disturbing metamorphic images that reflected Picasso's own weariness with the calm classicism that preceded them. In St. Louis there was an emphatic interest in German Expressionism, strengthened by the presence of Rathbone at the museum, Janson (who had moved from Iowa to Washington University), and a number of easily influenced collectors. It was there that Guston first saw Beckmann's monumental Voyage and numerous smaller originals brought personally by the New York dealer Curt Valentin. Guston returned to the monograph he had bought at Valentin's gallery years before, renewing his interest in "the compressed pictures of World War I, the 1922–23 'loaded' pictures." He also frequented the exceptional collection of the newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer, Jr., who specialized in modern art and had a particularly good collection of Picassos.

In 1946, a year after his arrival in St. Louis, Guston was joined by his erstwhile student Stephen Greene, who had been appointed an instructor at Washington University. They resumed their old conver-

sations, but Guston was beginning to take issue with the German Gothic painters, finding them too narrative and illustrational. His renewed interest in Picasso at the time was mounting. At the same time, both Greene and Guston were much troubled by the tragic revelations that had followed the close of the war in Europe. Guston recalls that they had seen films about the concentration camps. "Much of our talk was about the holocaust and how to allegorize it." But where Greene felt a need to be a "tragic" painter, Guston "was searching for the plastic condition, where the compressed forms and spaces themselves expressed my feeling about the holocaust." The level at which these horrifying documentaries entered Guston's consciousness was deep enough to mark his work for the rest of his life, as the paintings of the early 1970s attest. The gloomy news items flowing into St. Louis during the two painters' sojourn there affected them profoundly; Greene recalls that it was a "tortured period" in both their lives. "We had times when at 12 or 1 in the morning the two of us would sit in his car and let bus after bus go by and very often we had tales of woe to tell about ourselves."[3]

In his unsettled state, Guston was paradoxically affected by the sudden attention he received in the national press. As a result of his having won the Carnegie award. Life magazine compiled a feature story that appeared in the issue of May 27, 1946. On the lead page is a photograph of Guston, head thrust slightly back as though to ward off the spotlight, frowning slightly, standing before his most recent painting (which he subsequently destroyed). The details of the painting indicate a radical shift toward abstraction, noted by the headline: "Carnegie Winner's Art Is Abstract and Symbolic." A dense whirl of shapes very close to the picture plane, dissected and reassembled in small units, is reminiscent of Picasso and of those paintings by Pollock that derived from Picasso. In the story, Life underlines Guston's rapid rise to fame, proving it by the old American gauge—the high prices he could command.[4]

By the time the Life story appeared, it was old news from Guston's point of view. He had already returned to earlier interests and was thinking about de Chirico's mannequins, the frescoes in Siena, and the little panels of the Lorenzetti brothers. The endless sagas of torture and torment enclosed in the gilt frames of the Italian Quattrocento displaced once again the muted dreams of the Venetians. In the paintings finished between 1945 and the end of 1947 there are allusions to punishment by crucifixion, by quartering, or by hanging upside-down—never explicit but nevertheless unmistakable.

He adopted a new way of indicating space. Since the space he wished to depict was claustrophobic, confined as a narrow prison cell, the recession in depth had to be truncated. Forms lay on a precisely defined picture plane with only flat overlays suggesting a modicum of depth. As Janson was to write in the February 1947 issue of the Magazine of Art, "there is no distinction any more between figures or setting, between the formal and representational aspects of design." The adjectives Guston had found for Beckmann's earlier paintings—"compressed" and "loaded"—could now serve for his own works.

Few paintings of the St. Louis period have survived. The cast of characters from If This Be Not I lingers only in reproductions. The new figures are masked or paper-hatted, and they blow horns or clash cymbals. But severe frontality has forced the artist to depict them in a far more abstract way. The compositions are generally cruciform with figures grouped in a Cubist progression from the center outward. There is enormous pressure from the foreplane to the rear, flattening everything in the narrow confines of the composition. The melancholy emanating from such paintings is heightened if one recognizes the peculiar repoussoir used in several of them: the sole of a shoe painted as though it were affixed to the picture plane pushing the other objects

Performers , 1947. Oil on canvas, 48 x 32 in.

back into a disturbingly indeterminate but confined space. The columns, horns, spires, and buildings (in which the windows are now barred) are steamrollered flat. Details such as moldings and architectural motifs are less readable, but there are frequent reminders that this is a painter's world of reality, an allegorical one. In Porch, for instance, the window shapes are clearly picture frames. In the paintings completed before he left St. Louis (he was replaced as Visiting Artist by Max Beckmann himself) shoes and masks proliferate, marking off the intervals and spaces in complex rhythms. Guston had again begun his study of Piero.

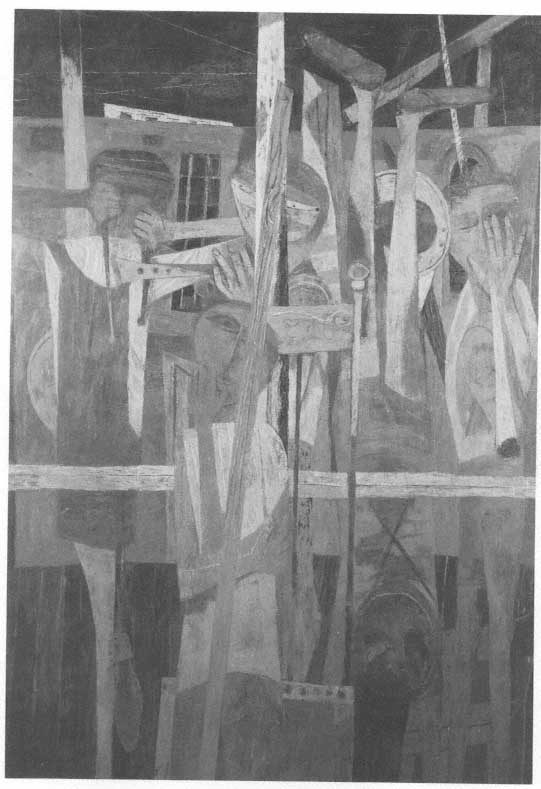

A second version of Porch was begun in St. Louis just before he embarked on a leave of absence in the spring of 1947 to take up a Guggenheim Fellowship. Increasingly disturbed and secretly hungering for a catharsis, Guston took his unfinished canvas with him. When he brought it to completion it was a harsh statement of emotional disequilibrium. Gestures of despair predominate, and the features of the faces recall, schematically, the unforgettable photographs of prisoners liberated from concentration camps. Jarring greens and oranges lie on the surface of the canvas in broken planes, suggesting a nightmare place. The uneasy marriage of purely formal, Cubist elements and a highly charged theme is made more obvious by a curious echo of the whole composition painted in grisaille at the extreme right, as though Guston's vision were cut off from some other reality that refuses to cede. This stiff and tortured painting was at once an end and a beginning, for afterward Guston slipped into the abyss that had long been awaiting him.

Outwardly there was every reason for Guston to feel at ease in the world. He had, by the age of thirty-four, won most of the major honors available to American artists of the time. He was deeply admired by students and colleagues. He had even had the rare luck to attract serious and authoritative writers, so that unlike many of his peers, he was not completely at the mercy of carping journalists. In fact, at about the time he left St. Louis to return to Woodstock in 1947, a long study of his recent work had just been completed by Mary Holmes, who summarized the St. Louis paintings in an article entitled "Metamorphosis and Myth in Modern Art."[5] She recognized the complex course of Guston's preoccupation with the mask, in which he had the wisdom to explore problems of identity and personality without slipping into the faddish language of his contemporaries.

In the symbol of the masked child, Miss Holmes saw the twentieth

Porch II , 1947. Oil on canvas, 62½ x 43 1/8 in.

century's "fearful adoration of the child" deriving from Rousseau and Freud. She noted that in Guston's paintings the figure of a bystander recurs, unmasked, or in the act of unmasking. "He still quails before his own prophetic act, yet the day may come when the mask may be dropped, because its fearful or playful necessity has been dispelled. The self, more unfathomable than any disguise, will be nakedly acceptable. The question 'If this be not I, who then may it be?' will be answered."

Miss Holmes, in her discussion of the half-unmasked bystander, recognizes that it is the artist himself who is, in the fullest sense, at stake. If her psychological reading of Guston's paintings is too elaborate, it is not wholly idiosyncratic. There can be no doubt that Guston himself saw the implications of his obsessions. Kafka could say "I carry the bars within me all the time" and Guston understood. No amount of reassurance from the outside world could dispel his suffocating sense of insufficiency during the next couple of years.

Guston's withdrawal to Woodstock accelerated his descent. While Woodstock was a three-hour drive from New York City in those days, it was a journey that many artists undertook. Some, like Guston, even settled permanently into modest cottages near rushing brooks, with pleasant wooded vistas and gentle hills in the background. Those who stayed after the summer season still received periodic visits from their New York colleagues; both Pollock and de Kooning visited Guston there. The news from New York City in 1947 was encouraging. Critics were beginning to focus on a small band of artists—many of whom Guston had known on the Project—as an authentic vanguard, and there were new galleries devoted to contemporary work. So eminent a critic as Clement Greenberg discerned a shift of interest among painters, away from Cubist principles toward "symbological or metaphysical content." Although Greenberg disapproved, he recognized that this symbolism served to stimulate ambitious and serious painting, allowing artists to lay aside their differences of ideology. In the suddenly open situation, many painters felt a surge of psychological independence; they felt free to experiment with modes they had never approached before. A strong current of exhilaration was sweeping through the artistic community, endowing a few artists with the giddy impulse to gamble with history.

The strong reverberation of this mood hit Guston on his occasional visits to Peggy Guggenheim's gallery in New York, where he saw many artists. The painter Bradley Walker Tomlin was working nearby

in Woodstock and was himself going through a conversion crisis. Guston had also come to know some other New York painters who occasionally visited—Mark Rothko, for instance, was in Woodstock when Guston had just finished Porch II, and when Rothko himself had taken the momentous decision to relinquish the suggestive symbols in his work of the early 1940s. Others, among them Barnett Newman, Theodoros Stamos, and Adolph Gottlieb visited Guston, bringing with them the newfound excitement of recent exhibitions and increasing public attention to what Rothko was to call their "enterprise." But when these visitors from a milieu Guston had once shared departed for the city, they left behind the sense of movement and displacement Guston was trying so hard to exorcise. During the long Woodstock winter he worked exhaustively, but it was not until spring that he had a glimmer of success.

In many ways Guston's move to Woodstock was a sign of his characteristic eccentricity. The logical place to go would have been New York. But in 1947, as on occasion in subsequent years, Guston's deepest need was to remove himself to find himself, which entailed a kind of self-imposed deprivation. He who loved to stalk the city streets was enclosed in the winter silence of Woodstock. He who had sought out people who could stimulate him in his quest for knowledge (and selfknowledge) limited himself to the company of a very few friends. Fortunately, they were exceptional people. Tomlin lived just down the road. He had evolved a delicate, quasi-Cubist mode of painting still lifes, which in the summer of 1947 was giving way to a fumbling emphasis on abstract calligraphy. Tomlin was attentive to the radical changes in mood among painters in New York and had long pondered his own work. By 1947 he had left behind his romantic semifigurative style and was about to evolve a congenial, highly individual abstract one. Guston and he met frequently, encouraged each other, and talked about painting. Occasionally they would be joined by the sculptor Raoul Hague, a rather reclusive woodcarver.

More often Guston saw the young writer Robert Phelps and his wife Rosemary Beck, a painter. Like Guston, the Phelpses had withdrawn to Woodstock to work. "We would work like mad all day and talk all night," Phelps recalls.[6] Guston, who was a fine midnight cook, would prepare various delicacies, among them potato pancakes, and they would eat and talk long into the night. Other times, they went to the movies. "We knew just about every movie house in the Hudson Valley," Phelps remembers.

Guston found in Phelps another in the long line of literary companions who have been endemic to his artistic life. Elegant, quick, full of enthusiasm, Phelps stimulated Guston's imagination. He lent Guston books, particularly ones by authors with whom he was particularly involved—Colette, Henry Green, Genet, and that curious author of some hundred works Marcel Jouhandeau. Throughout Jouhandeau's grisly epics of vice, crime, and blighted love runs a thread of Christian anger that aspires to metaphysics. The violence he portrays might have interested Guston particularly then, since he was himself casting about for ways to express his response to the Satanic events of which he was the half-unmasked witness. (It is interesting that Jouhandeau invented a leading character whom he called M. Godeau, anticipating the Godot of Beckett, soon to become another of Guston's key writers.) In addition to the French writers, to whom Guston was attracted for their superb sense of form, he and Phelps read Auden and Rilke. New translations of Rilke's poems were appearing regularly at the time, and certain of his prose writings were discussed in little magazines where the new leitmotif of the late 1940s was the problem of "alienation." Rilke's insistence that the artist must bear the inevitable isolation thrust upon him by his very success paralleled those attitudes of Kafka with which Guston was intimately familiar. Rilke outlined the stance of the romantic artist who can hope for no true solace from the outer world, and who can find only moments of emotional success in his immersion in the work of art. In Auden the notion of "anxiety" corresponded precisely to Guston's zigzag course through various literary sensibilities, which, for all its variety and divagation, seemed to cleave to the pessimistic, ultimately tragic tenor of what was to be much discussed within the next few years—existentialism.

These literary orgies (for Guston is capable of reading jags that are quite as obsessive as his painting sessions) fed his discontent and exacerbated his sense of esthetic disorder. As Phelps points out, Guston often thinks analogically. He speaks of pictures as though they were books and of books as though they were paintings. "He always talked about 'reading' a painting, and the 'language of paint.'" At the same time, he did not leave behind his old affections. There was talk about Piero, and about Watteau ("those powder blues!"), and about the American comic strip. Guston showed Phelps his paintings. "The first one I saw had that movement of feet, arms, and wrists typical of Philip himself when he talks." It also had, as Phelps recalls with amusement, the ubiquitous sole of the shoe, confirming Phelps's the-

ory that Guston was and is primarily an autobiographical painter, an American who has left nothing behind.

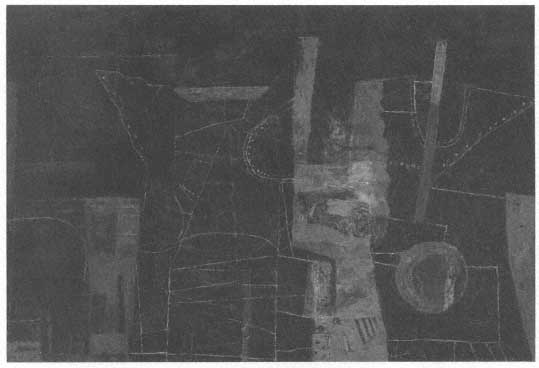

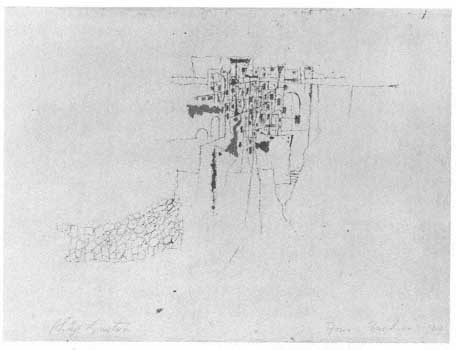

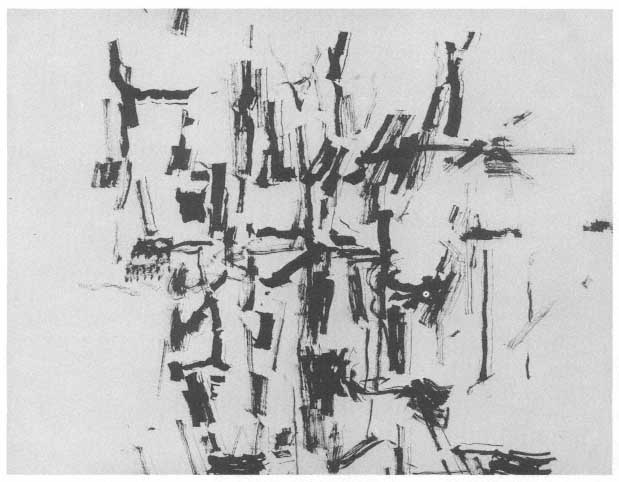

Toward the end of winter that year, Guston painted a small selfportrait in which he portrays himself in an unmasked condition of melancholy. Curiously, though he had long been out of touch with Gorky and de Kooning, the same grays and pinkish ochers they had used in their tentative figure studies of the early 1940s now predominate in Guston's painting. The reduction of color intensity, hinting at ineffable sadness, seems to lead directly into the nocturnal image that was to constitute the first in his extended series of abstractions. This, again, is one of the important paintings in Guston's oeuvre and was to serve as the initial impetus for many later works. Once again he reiterated a long-dormant theme—the ugly habits of the masked and hooded figures associated with the Ku Klux Klan, as he had painted them in The Conspirators some sixteen years before. In the preliminary drawing, fragments of representation are rendered in schematic line reminiscent of his caricature style. The sole of the shoe, its heel dotted with nails; the image of a city house in the background; a single head—these are the clues that this is, in fact, a thematic drawing. But the flattened shapes, somewhat like patterns, are by far the most telling elements. This painting, which he called Tormentors, car-

Tormentors , 1947–48. Oil on canvas, 40¾ x 60 1/8 in.

ries out the imperative of flatness and linear primacy. The claustrophobia formerly in evidence in the Porch paintings is excruciating here, where the artist has squeezed himself out of space entirely. The figures are disembodied—only vague, wavering lines indicate their erstwhile presence. A bell, perhaps a reminder of the horns that once played so important a part in his paintings, a crutch shape, a hint of a building are all that remain of his theme. In the darkness of this image, the thin lines, like the edges of welded plates, speak another language far removed from the preoccupations of the past few years. The human presences, both evil (the Ku Kluxers) and good (the children), have here abandoned Guston. In the murky brick red and black recesses of this painting still lay the host of questions with which Guston flogged himself like one of his own tormentors, and which would lead him to one failure after another for the few remaining months in Woodstock before he set off on his first pilgrimage to the sources. In October 1948, armed with a Prix de Rome and a grant from the American Academy of Art and Letters (his outer successes were still signal), he embarked for Italy. At a going-away party given by Jimmy Ernst, as though to foretell future associations, were a number of rediscovered friends from the Project days, and new friends who were moving rapidly into position as the progenitors of the New York School, among them de Kooning, Rothko, Gottlieb, and Stamos.

Guston's year abroad was fraught with anxious moments, but it was also a year of great excitement. For the first time he had a chance to see the originals of so many works he knew by heart from reproductions. "It was thrilling to go to Arezzo or Orvieto for the first time," he remembers. "I went to Arezzo many times, and to Florence. Seeing the frescoes, the Uffizi in Florence, and Siena excited and exhausted me."

He painted only sporadically. After the first month in Rome, he found that what he wanted above all was to walk the streets and feel free to think about what he was seeing. "In a sense I was searching for my own painting." Although he painted little, Guston drew constantly in Rome, but did not keep the drawings. A few drawings done on Ischia, where he had fled "to escape from the oppression of the masters," are extant, showing the artist in a very tentative and shifting mood. His restless wanderings in Europe took him to Spain, where he examined El Greco and Goya; to France, where he was moved by Cézanne and Manet; and to Venice where he took a long look at the "painterly painters" Tintoretto and Titian. These last he met with a newly speculative eye. Increasingly he felt the need to reconcile his two longstanding impulses—the one toward pure form, the other to-

Drawing No. 2 (Ischia ), 1949. Ink on paper, 11¼ x 15½ in.

ward pure expression. His exposure to Europe brought his long process of dismantling to its climax. Everything conspired to make this a moment of crisis for him. His chance conversations, in which the European view of contemporary life, conveniently labeled "existentialist" predominated. His reading, which veered more and more to the "tragic" writers. His feeling that he had left unattended something vital in his painting life, and that he must come to grips with painting itself in terms he had not yet fully comprehended. He had commenced the long peregrination to another place where symbol is all but eliminated, and where the act of painting is itself symbolical; but still, he had not yet succeeded in purging himself of the past, his own, and the past of painting.

In the fall of 1949 he returned to America and settled in Woodstock again, in a primitive house with pump and outhouse. But his work was not going well. That winter he and Tomlin decided that they needed to be in the city, so they took a loft together at University Place and 13th Street, for which Franz Kline constructed the partition. Tomlin soon moved to another loft, and shortly thereafter Guston moved into 51 West 10th, where he stayed for several years. His relationship with

Tomlin remained close, and the two of them, along with the painter Mercedes Matter, often spent their evenings together. It was around this time that Guston began to feel an urgent need to "see if I could paint a picture without stepping back to look at it…not only to suspend criticism but also to test myself, to see if my sense of structure was inherent." He had been commuting from Woodstock, but now he decided to move permanently to New York. Fortunately, his old friend Janson was now at New York University and arranged for him to take up a teaching post in the fall of 1950. At Guston's specific request, it was not a painting class, but a freshman drawing class in which Guston took attendance and gave grades; his students did not even know he was a painter. "I wanted this anonymity and noninvolvement which in time became boring." Yet, except for a spring term in 1950 when he taught graduate painting at the University of Minnesota at the invitation of H. Harvard Arnason (whose interest and support led eventually to a large show at the Guggenheim Museum in 1962), Guston refused to go back to teaching painting until the 1970s.

When the Gustons finally moved to the city late in 1950, he was fully recovered from his long depression. "I had worked for three years and ended up with a kind of…freedom." His catharsis in this case, as in other times in his life, consisted in an overwhelming need to forget his culture, above all his painting culture, and to engage himself, almost as a drugged poet might, in the total absorption of painting itself. The two sides of his nature in their constant contention had exhausted and exasperated him. He was ready, as Flaubert had been, to gamble with the muse. "What seems beautiful to me," Flaubert once wrote, "what I should like to write, is a book about nothing, a book dependent on nothing external, which would be held together by the strength of its style, just as the earth, suspended in the void, depends on nothing external for its support; a book which would have almost no subject, or at least in which the subject would be almost invisible, if such a thing is possible."[7] Guston's personal hegira to the void, the void as Flaubert and Mallarmé understood it, and as Sartre and Camus later discussed it, coincided with the collective movement that was to be known as the New York School. One after another artists abandoned the familiar, and the nature of painting quickly converted itself into a view of existence. Painters as different as Rothko and Pollock shared in the general feeling that at last the nature of painting was undergoing a vital transformation. It could become, as they repeatedly stressed, a way of life, an expression of the

human condition—an activity rather than a horde of objects. The complex attitudes of the Abstract Expressionists, as stated in their arguments at the Artist's Club, or as quoted by their increasingly respectful critics, frequently coincided with the old preoccupations Guston had carried along for years. His sudden appearance in the midst of this energetic ferment was not unheralded.

No matter how the existence of the New York School is assessed, the fact is that a certain tremendous force of energy was propelling artists into more and more audacious activities, particularly during the late 1940s and 1950s. Guston was not immune to the nervous excitement that accelerated the pace of change in the work of so many artists. He was, on his own terms, completely ready for it. His view of the period, expressed in a lecture at Boston University in 1966, does not differ from the views of most of the others who shared in the adventure. He looks back and sees that what affected him was "a sense of embarking on something in which you didn't know the outcome." Officials, he said, tended to see it as a style, and in America, with its passion for change and the generation of new emotions, styles come and go. But Guston sees it as "a revolution that revolved around the issue of whether it's possible to create in our society at all—not just to make pictures, because anyone can do that." The real questions raised by the activities of the New York School were whether painting and sculpture were not in fact archaic forms in our industrial society. "The original impulse of the New York School was that you had to prove to yourself that the art of creation was still possible," Guston says. "I felt as if I were talking to myself, having a dialogue with myself. The revolutionary aspect was that nothing could really be decided. A painting would have to be a continuing argument." His own continuing argument merged with the arguments that were spurring his confrères. His personal need coincided with a strong cultural current that was setting everyone adrift in experience itself, in the quest for direct experience unmitigated by rational procedure. The emergence of Care, or Anxiety, as a painterly ideal (the painting being both an anodyne and a vehicle) was notable even in the vocabulary employed in numerous discussions at the Club. Later, younger artists were to smile at the earnest preoccupation with "risk" among the Abstract Expressionists, but at the time, in the early 1950s, there was a strong need to be aware of the dangers implicit in headlong rebellion. It was risky to leave behind the containing structures of painting tradition in order to find a new freedom that did not even have a name.

Drawing , 1953. Ink on paper, 17½ x 23¼ in.