V—

If This Be Not I

During the four academic years Guston spent at Iowa, he developed his historical sense in depth. His painting experiences were divided. He was in the process of completing a mural commission for the Social Security Building in Washington on the theme of public communications. His conception of the mural shows him straining away from specific "social consciousness," dissociating himself from the earlier ideological tendencies of the mural movement. Instead of a social scene, he paints a rural idyll that includes a loving description of a still life and even—something very rare for him—a landscape with formal trees. That he was intent on breaking with the mural painter's habits and commitments was confirmed in one of the increasingly frequent articles on his works, an essay appearing in the March 1943 issue of Art News and dealing with the Social Security murals. Guston is quoted as saying: "I would rather be a poet than a pamphleteer."

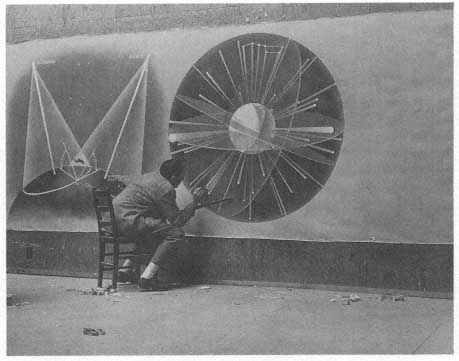

All the same, obligations remained. The United States was at war, and, as everyone without exception believed in those days, it was a just war. Guston, like many other painters, felt obliged to contribute his talents in any way possible. As it happened, he found that he could use his ability as a draftsman. Turning from his easel, he attended

classes in celestial navigation, in order to be able to produce murals as visual aids for pre-flight training in the naval air force. Gouaches reflecting his earlier mural style were used to illustrate two articles in Fortune magazine in 1943. Even during this period, life for him was divided. There were the long conversations in the Student Union, sorties to the movies to see Hayworth or Bogart or whatever movie came to Iowa City, and there were the long nights in the studio where the artist withdrew to revise and reconsider. In retrospect, he thinks of the entire period ruefully: "In 1941 when I didn't feel strong convictions about the kind of figuration I'd been doing for about eight years, I entered a bad, a painful period when I'd lost what I'd had and had nowhere to go. I was in a state of dismantling."

His strongest need seems to have been to rid himself of the overtones of monumentality. He began to paint studio pictures—agreeable arrangements of figures, objects, windows, still lifes, and even portraits of his wife and friends. These were pure exercises in painting, part of an attempt to overcome the challenges thrust forward by his

Guston in 1942, painting celestial navigation murals for the Navy.

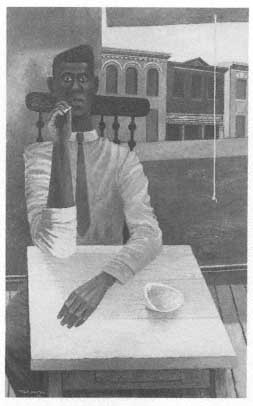

Sunday Interior , 1941. Oil on canvas, 38 x 24 in.

intellect. They were, for a time, rather conventional, and a shade sentimental. His determination to be a poet and not a pamphleteer led him to soften his address both to composition and to color. He painted Iowa City in elegiac terms—in Sunday Interior we can see a window giving on the street, its light oblique and softened by a window shade, whose string is painted with the deliquescence of a Corot. Guston's portrait of his wife and child shows faint reminders of Picasso and clear references to the shaded and graded chiaroscuros of traditional studio painting. His portrait of a student is carefully worked up and posed in an utterly stylized way.

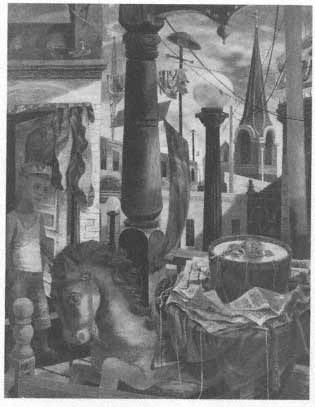

But then comes the stirring of his old ambitions in Sanctuary, 1944, a complex composition with the figure of a reclining boy in a state of reverie, his face cast in deep shadow and all but masked by his hand. Behind him is the flattened Italianized profile of Iowa City, reminiscent of Guston's earlier de Chiricoesque arcades. (Years later, recalling Iowa in a letter, Guston wrote: "You say 'flat and hermetic'—yes, but also emptiness, the lonely quality of it. Not only Iowa City but

towns like Decatur, Illinois, and Des Moines, etc., with lonely empty squares, 'Gothic' City Halls, armories, big clocks illuminated at night. Railroad Stations. Trains. Soldiers moving around—the war years.…" His technique in this painting is emphatically in the painterly tradition, with a flutter of half-tones animating the surfaces of skin and cloth and sky, but the artist here has returned to his earlier, larger ambition. In Holiday, the ideals that had lain dormant for a few years have surged forward. This reprise of the children's game motif is couched in the complex language Guston relished in Martial Memory. The jumble of objects includes a hobby horse, a rendering of a typical midwestern house, a child looking on, and a rose on a drum; these are held in a tense balance and brought close to the picture plane. The manner is softened, but the echoes of the intricate composition are strong. In the upper section, an array of lamp posts, church spires, and housetops—the forms of Iowa City—herald the crowning work of the period, If This Be Not I.

Into the calm period of the portraits, during which Guston had attempted to establish his newfound ease in oil painting, has intruded his increasing suspicion that a willful turning away from the modern abstract tradition was somehow false. (When the plaudits of his happy viewers began to pour in, he reacted strongly and eventually denounced the work of this period in public.) Around 1944 he began to look back to experiences he had had in New York. He renewed his interest in the darker tradition, in the Expressionists, and thought about the work of Max Beckmann, which he had seen in 1938 at the Buchholz Gallery. At the time he had bought a monograph on Beckmann and was probably familiar with certain of Beckmann's biographical data that would have seemed significant to him. Beckmann, like Guston, had been particularly moved as a student by the works of Piero and Signorelli, and he had also made a close study of Rembrandt. Beckmann had a literary turn of mind and in addition to painting wrote four plays. He also rejected the notion of total abstraction in terms Guston would have immediately understood: "I hardly need to abstract things, for each object is so unreal that I can only make it 'real' by painting it." Beckmann did not put great emphasis on color ("Things come to me in black and white"), but he developed strong abstract means of suggesting spatial transitions, especially in his bold employment of black, which he dextrously made to serve simultaneously as delineator, modulator in space, and shadow itself. For Guston, whose determination not to fall into modernist clichés led him

Holiday , 1944. Oil on canvas, 42 x 56 in.

away from Cubism around 1943–44, Beckmann's alternatives held special interest.

This interest was fanned by the presence of H. W. Janson and Stephen Greene, who though his student was only four years younger. Together they pored over books containing reproductions of works of the Northern Renaissance. Guston remembers studying Michael Pacher and Grünewald's Isenheim Altarpiece closely, while Greene remembers analyzing Hugo van der Goes. These were new sources for Guston, who in the past had familiarized himself only with the Italian Renaissance, and they were to prove important as he gradually pulled together his various interests and began to summarize this period in his work.

The summum, as Guston himself has said, was If This Be Not I, a painting that became a whole year's project, in which, for the first time, he felt he had really mastered oil painting. The title had been suggested by Musa, who told Guston the Mother Goose story about an old woman who had lost her identity. (Versions of the rhymed tale

exist in some eight languages, showing the elemental nature of this human problem.) It was the right psychological moment for Guston to undertake a synoptic exploration of his own painting history and of the motifs that had repeatedly come to the surface of his imagination. The problem of identity itself had become more pressing as Guston matured. His immersion in literature exacerbated his natural introspective quality, which had for so long led him to resist settling into a definite mold.

A new sense of the positive value of doubting becomes evident in If This Be Not I. The entire tableau is enacted in a round of ambiguities, one illuminating the next, but none totally dispelling a sense of mystery. In the painting Guston carries along the props already familiar from earlier works, particularly the Queensbridge mural and Martial Memory, but the entire psychological context is changed, and so is the content. There are the familiar paper hats, bedposts, doors, light bulb, newspapers, and ropes arrayed against the background with a Venetian blue sky and the forlorn line of spires and chimneys of the mid-western town. Yet, despite the allusions to other works of his own and to works of the masters he admired, Guston made of this picture an ambitious allegory that was widely recognized as being entirely personal.

Viewers familiar with his oeuvre to date could note that the Harlequin he had once used in his mural cartoons and in his drawings now stands leaning, in Renaissance fashion, over a balustrade, his eyes nearly obscured by his paper hat. Immediately behind him is a child changing into costume with his back to us, certainly an homage to the figure in Piero's luminous drama The Baptism. In the plane immediately behind these are fully masked figures. There are many arcane iconographical references, as in the child's figure in the extreme left foreground holding a tin horn and suggesting, in his rigid horizontal pose, a fallen angel, or as in the child standing behind holding a bandage across his eyes in the manner of Renaissance allegories of Justice. There is even an allusion to the Cubist interest in African masks in the figure ringing a bell. These images do not, however, add up to a painting fit only for the iconographer's mill. The overwhelming impression is one of mood and atmosphere, of stillness and mystery, of sublimated ritual.

Although Guston retrieves the closely orchestrated planar conception of his earlier Martial Memory (the series of horizontals reading back in highly condensed spaces held by the prominent verticals of the white columns) and remembers his admiration for the piling-up of

detail in de Chirico (as well as the latter's preoccupation with time, which we can see in the clock against the blue sky in Guston's painting), he infuses his composition with the spirit of his recent experiences. The condition of reverie, with its unaccountable images slipping one into the other, overcomes even the theme, which is still that of slum children in their ritual games. Here, as in other similar moments in his painting life, melancholy softened by memory reigns supreme and fuses objects and environment into an atmospheric whole.

The oblique character of the motif corresponds to Guston's expressed desire to stress poetic rather than topical values. He deliber-

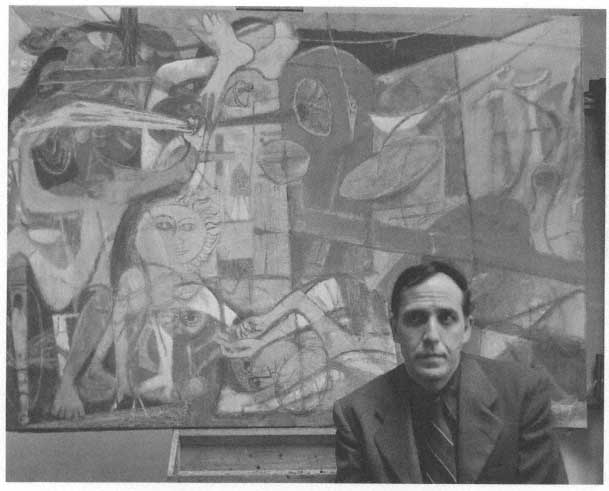

Guston in his St. Louis studio, 1945. (Piaget)

ately softens the light in a theatrical manner. Indeed, the whole scene is placed before us as if behind a proscenium. Even the ropes dividing the intersecting planes are deployed as though they were the mechanical backstage aids. If This Be Not I takes its place in a tradition that filters down to Guston from the eighteenth century. He has obviously looked closely at Watteau and at the Venetians, especially the two Tiepolos. In the delicate play of whites of the prominent seated figure—hat, shirt, and trousers—there is a distinct recall of Tiepolesque delight in animating various white fabrics. In the beaked mask worn by the boy, significantly just below his transfixed eyes, the history of Italian masqued festivals as transmitted by the Venetian painters of the Rococo period springs to life. Guston has taken pleasure in numerous virtuoso passages in which textures of cloth, paper, and metal are illuminated in the pale, heightened palette of the Venetians. In the half-tones that gently shift from one minute plane to another, Guston has found a universe that reflects his perception of the ambiguities implicit in existence.

Aside from the obvious implications of the mask, including its symbolic commentary on painting itself, Guston here states an almost reflexive interest in the parallels between the process of painting and the process of producing a theatrical drama, bracketed as it is between life and illusion, between proscenium and hall. It is not so far from seeing a painting as a drama to seeing it as a trial. The oblique theatrical character of If This Be Not I, with its statement of allegory rather than mimesis, is germane to Guston's entire oeuvre. In 1945 he would certainly have shared the recently revived interest in the Italian commedia dell'arte, and in Watteau and his eternally dreaming Gilles, that had flowed through the entire nineteenth century and into the twentieth via the Romantic poets. Guston, like his predecessors, was in a state of rebellion against the demands of the "realists," and like them, he had undertaken an introspective quest, as the title of the painting emphasizes. (Those who know Guston's grave face will recognize his own eyes in each of the figures of the painting.) All true art, as Kafka said, is a statement of evidence.

The evidence here is softened, obscured, made to retreat behind a theatrical scrim, but it is evidence nonetheless. For those who, like Verlaine, Rimbaud, Baudelaire, Gautier, and later Apollinaire and Valéry, recognized artifice, ornament—in fact, the basic qualities of eighteenth-century art—as essentially expressive, the evidence must always be filtered through the poet's form-giving imagination. In Bau-

delaire's poem of admiration to artists, "Les Phares," he speaks of Watteau:

Watteau, ce carnaval où bien des coeurs illustres

Comme des papillons, errent en flamboyant,

Décors frais et légers éclairés par des lustres

Qui versent la folie à ce bal tournoyant.

Watteau, that carnival where many illustrious hearts,

Like moths, wander as flames catch them,

Fresh, light decors illuminated by chandeliers

Which pour madness over the turning dance.[1]

Baudelaire's recognition of the essentially theatrical quality of Watteau (the light of the torch, so bright but so oblique when compared to daylight) is echoed by other Romantic poets, who saw in the use of the theatrical metaphor a larger metaphor for art itself.[2] The poet Banville writing of Verlaine defined him thus: "Il est des esprits affolés d'art, épris de la poésie plus que de la nature, qui, pareils au nautonier de L'Embarquement pour Cythère, au fond même des bois tout vivants et frémissants rêvent aux magies de la peinture et des décors." (He is one of the spirits mad about art, taken more with poetry than with nature, who, like the helmsman of The Embarkation for Cythera, even in the heart of the living and breathing woods dream of the magic of painting and decor.) There is a deep strain of this passion for painting and decor in Guston, in themselves and in their theatrical illusion. It would hardly be necessary to speak of distant nineteenth-century forebears. The interpretation of the artist as a conjurer, a clown (the broken-hearted saltimbanque), and as someone who enacts the human condition in a stylized ritual has appeared frequently in our century. Picasso dwelt for nearly seventy years on the theme, and it is prominent in the works of many other artists, including such filmmakers as Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini.

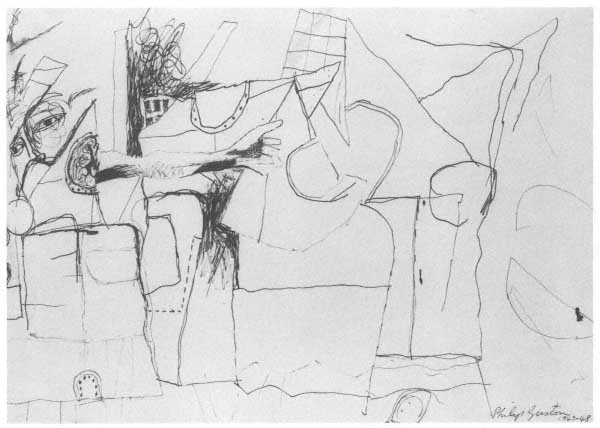

Drawing No. 1 (for Tormentors ), 1947. Ink on paper, 15 x 22 1/8 in.